EDUARDO CESARFigure of Albert Einstein at Estação Ciência, in São PauloEDUARDO CESAR

Even though young people live in a world surrounded by technology, whenever someone asks an adolescent what he or she wants to be when he or she grows up, the answer will hardly ever be “ a scientist.” According to the research study Los estudiantes y la ciência, a project of the Iberian-American Science, Technology and Society Observatory (Ryct/Cyted), organized by Argentinean Carmelo Polino, only 2.7% of the high school students (from the ages of 15 to 19) from Latin America and Spain considered a career in the fields of exact or natural sciences, such as biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics (agricultural sciences were barely mentioned). The research study was conducted in the period from 2008 to 2010, and involved approximately 9 thousand public and private schools in seven capital cities: Asuncion, São Paulo, Buenos Aires, Lima, Montevideo, Bogota and Madrid. Strangely enough, 56% of the respondents said they were interested in social sciences, and one-fifth said they would like to go into engineering. The Brazilian team involved in the project came from the Journalism Laboratory (Labjor) of the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). The team was headed by linguist Carlos Vogt, and was responsible for the book´s chapter on “Informative habits in science and technology.” The book was published in Spanish and is available for downloading only through the following link: www.oei.es/salactsi/libro-estudiantes.pdf.

“This data is reason for concern in societies whose economies are in dire need of scientists and engineers; not many young people are interested in these professions. The alleged reasons are equally discouraging: 78% of the students justified their option because they feel that the exact and natural sciences are ´too difficult;´ nearly one half of the students said that these sciences are ´boring,´ while one fourth of the students stated that these professional fields offer few job opportunities,” says Polino. “The number of science students is at a level which is insufficient for the needs of the economy and industry, and, above all, insufficient to deal with the issues that societies will face in the future.” Still according to the respondents, the discouragement resulting from the challenges posed by the sciences is mostly related to the way the sciences are taught in the classroom. In addition, students complain that the resources used in the classroom are limited. One half of the adolescents say that science subjects did not increase their appreciation for nature, and they do not believe that the sciences are sources of solutions for the problems of daily life.

“There are cultural barriers, because today´s adolescents believe they don´t have to study a lot to earn money or be successful. They can choose a career that brings economic benefits quickly. An effort-related culture, which is the culture of science, is losing space. There is an urgent need for a public policy focused on science education and communication,” Polino says. The new research study reinforces some trends noticed in the previous study conducted by the group in 2004: Public perception of science (see Images of science in nr. 95 of Pesquisa FAPESP; Elusive readers, in nr. 188; and Advances and challenges, in nr. 185). The new research study, focused on adolescents, has added new data that raises concerns. “ A country such as ours, the future of which depends on scientific and technological progress, and in which the numbers show that there is a significant lack of professional technicians and engineers, demands the attention of government authorities and society in general to raise the interest of these young people in scientific careers. This is a paradox, because we live in a world that is surrounded by technology in all aspects of people´s lives,” says Vogt. “We appreciate the benefits stemming from scientific efforts, but we are not interested in continuing this work. Facilities are offered, but they are an illusion, because if we want to take ownership of these achievements we need to have scientific capacity building, abstraction capabilities, notwithstanding the difficulties that result from the study of the exact and natural sciences.”

“There are cultural barriers, because today´s adolescents believe they don´t have to study a lot to earn money or be successful. They can choose a career that brings economic benefits quickly. An effort-related culture, which is the culture of science, is losing space. There is an urgent need for a public policy focused on science education and communication,” Polino says. The new research study reinforces some trends noticed in the previous study conducted by the group in 2004: Public perception of science (see Images of science in nr. 95 of Pesquisa FAPESP; Elusive readers, in nr. 188; and Advances and challenges, in nr. 185). The new research study, focused on adolescents, has added new data that raises concerns. “ A country such as ours, the future of which depends on scientific and technological progress, and in which the numbers show that there is a significant lack of professional technicians and engineers, demands the attention of government authorities and society in general to raise the interest of these young people in scientific careers. This is a paradox, because we live in a world that is surrounded by technology in all aspects of people´s lives,” says Vogt. “We appreciate the benefits stemming from scientific efforts, but we are not interested in continuing this work. Facilities are offered, but they are an illusion, because if we want to take ownership of these achievements we need to have scientific capacity building, abstraction capabilities, notwithstanding the difficulties that result from the study of the exact and natural sciences.”

“Young people entering the science professions face enormous obstacles. This profession is viewed as being hermetic, a field for experienced people, with its own language and hardly any relationship with the world we live in. It demands a high degree of abstraction, and it is not always easy to find analogies with the students´ personal lives,” Vogt points out. “Imagine this kind of situation in a country such as ours, in which only 2% of the graduating students manifest a desire to go into the teaching profession. Our educational system is in a sorry state; in most cases, science teachers come from other fields, such as engineering or medicine, and are not at all interested in facilitating or renewing their teaching methodology.”

Thus, the reasons that drive a student to choose a scientific career are very subtle. According to the survey, 4 out of every 10 students choose this field for two reasons: it entails extensive travelling and working with new technologies. One third of the students said that the salary – considered to be attractive – is a variable to be taken into consideration. Other reasons such as new findings, solving humanity´s problems, and making knowledge advance, account for less than 18%. Still other reasons, such as having a socially prestigious profession or working with highly qualified people, account for less than 5%. In terms of the reasons that discourage youngsters, the biggest “villain” is the methodology with which the sciences are taught in the classroom. The teaching approach results in a lack of motivation among students and discourages them from trying out for a scientific career or from a future in the science lab. For 6 out of 10 students, the difficulty they have in understanding the subject matter is a negative filter. “Boredom” affects one half of the students. The idea that upon choosing a scientific career means that they will have to continue studying something boring “forever” is another factor that discourages the students. The fear of having few job opportunities in the field of the sciences accounts for 24% of the rejection.

This does not prevent young people from viewing those who choose a career in the sciences as people with social prestige, whose work is associated with altruistic objectives and progress. The predominating image that they have of scientists is that of a person who is passionate about his or her work, has an open mind and a logical way of reasoning. The stereotyped image of the “solitary” scientist, “out of tune with reality” no longer predominates. However, there is a controversial aspect to this: most young people are convinced that scientists have a higher intelligence, which although viewed as a positive and attractive characteristic, drives young people away, who see themselves as being unable to reach such lofty levels as those of these “ exceptional people.” This view also has a negative impact on the decision to follow a career in the sciences. “ We have to analyze this data on the basis of its potential, because it is possible to change the current paradigm to revert this situation, thus not only attracting more young people to a career in the sciences, but also to improve their high school learning experience,” Polino emphasizes.

Seven out of every ten respondents agreed with the following statement: “Science brings more benefits than risks to people´s lives.” The statement “science and technology are producing an artificial and dehumanized life style” elicited less defined opinions and the recurrent response (21.5%) was “I neither agree nor disagree.” The social context revealed some interesting aspects: students from public schools are less enthusiastic about the conveniences offered by technology. “It is not surprising that those who have less access to technology fail to perceive its importance in terms of facilitating people´s lives,” Polino points out. The responses to “contradictory” statements such as “science is eliminating job positions” and “ science will provide more job opportunities for future generations” reveal that more (37%) young people are afraid of losing their Jobs because of science than the number of youngsters (32%) who are optimistic about the future. According to the researchers, the responses follow the pattern of Latin American adolescents for whom “meritocracy” at work is a myth rather than the reality. Everything gets worse when the environment is in the spotlight.

Seven out of every ten respondents agreed with the following statement: “Science brings more benefits than risks to people´s lives.” The statement “science and technology are producing an artificial and dehumanized life style” elicited less defined opinions and the recurrent response (21.5%) was “I neither agree nor disagree.” The social context revealed some interesting aspects: students from public schools are less enthusiastic about the conveniences offered by technology. “It is not surprising that those who have less access to technology fail to perceive its importance in terms of facilitating people´s lives,” Polino points out. The responses to “contradictory” statements such as “science is eliminating job positions” and “ science will provide more job opportunities for future generations” reveal that more (37%) young people are afraid of losing their Jobs because of science than the number of youngsters (32%) who are optimistic about the future. According to the researchers, the responses follow the pattern of Latin American adolescents for whom “meritocracy” at work is a myth rather than the reality. Everything gets worse when the environment is in the spotlight.

In relation to the statements “science and technology will eliminate poverty and hunger in the world” and “ science and technology are responsible for most of the environmental issues,” 3 out of every 10 students do not believe in the “ healing” power of science; this proportion is repeated in relation to the statement that science has a negative effect on the environment. As for women, they are more skeptical; 5 out of every 10 girls reject the idea that technology has the ability to end global problems. In general, but the adolescents are quite optimistic: 52% are open to and in favor of the things that science and technology can do for our society. They no longer have blind faith in the results provided by science and technology and are more moderate on and aware of the risks entailed than adults are. The researchers believe that if this attitude is dealt with properly, it will become the base of a more critical and responsible notion of citizenship. “Nowadays, building a nuclear power plant in Angra without consulting society is something unthinkable. Adolescents believe in the existence of a system that emphasizes democratization in scientific processes, which does not imply voting on who is going to the laboratory or not,” Vogt points out. “They accept a scientific culture that materializes a link between reason and humanity, between science and society.”

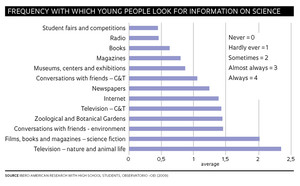

This might explain an interesting piece of information found in the research study conducted by Labjor. For adolescents, the main path to scientific knowledge is still the television, followed by the internet. Science fiction in the form of books, films, comic books, or games ranks third as a source of information on science. “Next to the internet, these different means have a great potential to attract adolescents to science in an interesting and pleasurable form; these means are a strategic manner of reaching out to this segment of the population to divulge scientific topics,” Vogt emphasizes. At various places where the research study was conducted, official institutions were barely known and sometimes even ignored by the respondents. Places such as museums and zoos, sources of information on science, were also unfamiliar. Strangely enough, a city like São Paulo, which has many research centers, universities, and where access to scientific information is supported by the existence of museums and media forms, showed that the consumption of information by the population is below average.

This might explain an interesting piece of information found in the research study conducted by Labjor. For adolescents, the main path to scientific knowledge is still the television, followed by the internet. Science fiction in the form of books, films, comic books, or games ranks third as a source of information on science. “Next to the internet, these different means have a great potential to attract adolescents to science in an interesting and pleasurable form; these means are a strategic manner of reaching out to this segment of the population to divulge scientific topics,” Vogt emphasizes. At various places where the research study was conducted, official institutions were barely known and sometimes even ignored by the respondents. Places such as museums and zoos, sources of information on science, were also unfamiliar. Strangely enough, a city like São Paulo, which has many research centers, universities, and where access to scientific information is supported by the existence of museums and media forms, showed that the consumption of information by the population is below average.