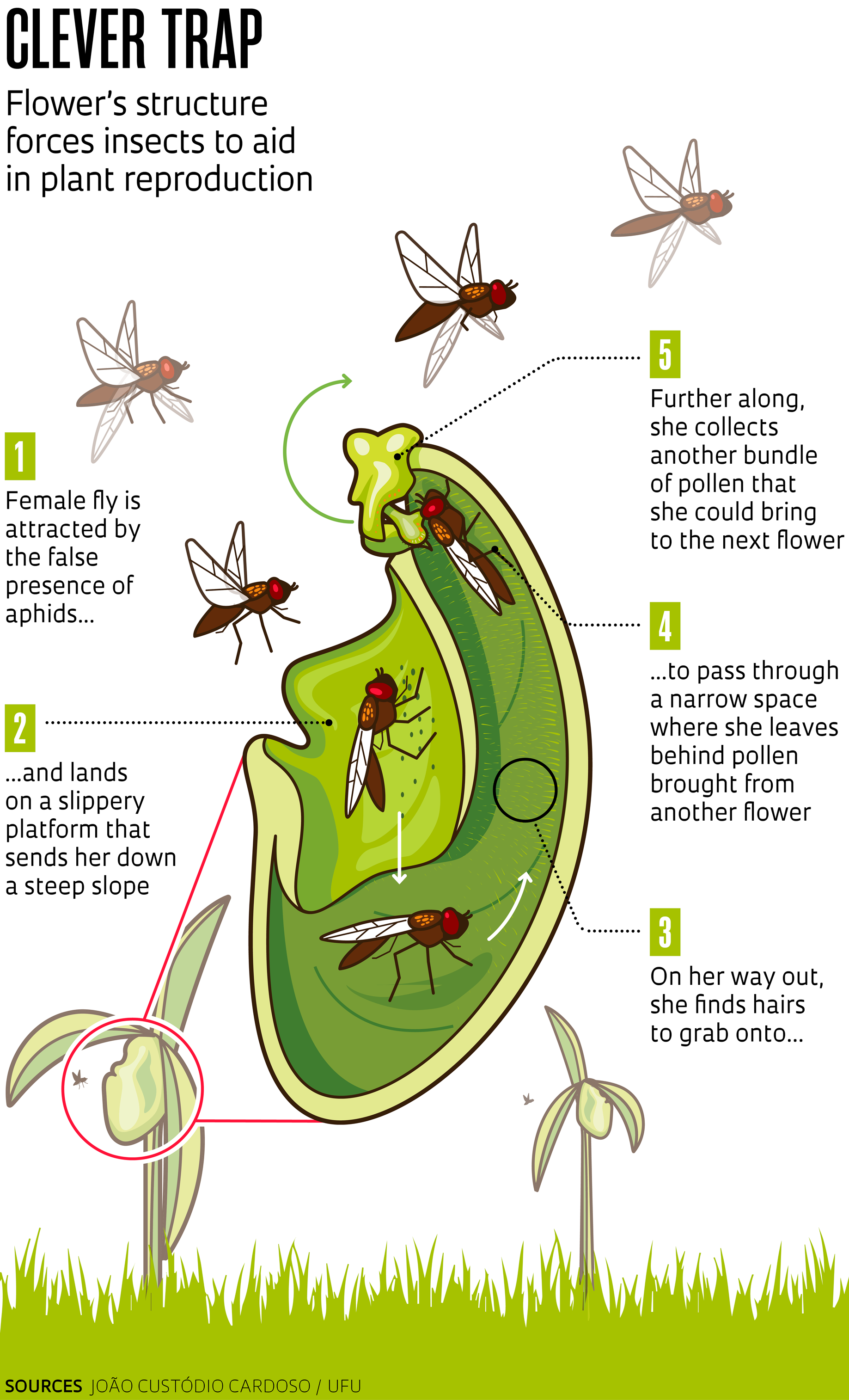

A scene from the Brazilian Cerrado: a fly flits over the greenery in search of the ideal place to lay the hundreds of eggs it carries in its abdomen. And then, she comes across a flower teeming with aphids, small insects crucial to the fly larvae’s diet. Perhaps the fly is too busy to notice that the aphids are fake, because as soon as it lands to start ovipositing, it slips and begins plummeting into the flower. This description of the trap employed by the Phragmipedium vittatum was published by the team led by biologist João Custódio Cardoso, of the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU), in February’s edition of Annals of Botany. During their observations, researchers identified mainly two species of flower flies: Allograpta exotica and Dioprosopa clavata, both from the family Syrphidae.

The flower that deceives the flies, P. vittatum, is a species of orchid from Central Brazil that is highly sought after by collectors and is therefore at risk of extinction. The genus Phragmipedium comprises species known as slipper orchids, whose lower petal (lip) has a distinctive pocket or slipper shape.

João Custódio Cardoso / UFUAmong the various pollinators that frequent the slipper orchid (above), typical of Central Brazil, is the flower fly Allograpta exotica (below)João Custódio Cardoso / UFU

Flower flies are considered excellent pollinators for some plants and are often used in farming for organic pest control, precisely because of their larvae’s fierce appetite for aphids that suck the sap from plants, potentially damaging entire crops. Another distinctive characteristic of this group of flies is that they resemble bees, which protects them, for example, from being attacked by birds.

Cardoso explains that, generally, slipper orchids do not provide insects with resources like nectar or oils, but they attract them with specific shapes, colors, and smells. Once deceived, the flies carry out pollination without receiving anything in return. The pollination process begins when the orchid attracts the fly’s attention, as it can carry thousands of pollen grains from a previous visit on its back like a large backpack. The flies are attracted by both the black spots on the flowers that mimic aphids, food for their larvae, and by the more common characteristics that attract the attention of these insects, such as the yellow color.

After slipping down the wide and slimy lip, the fly tries to crawl back out to freedom, but is unable. The only possible route is traversing the internal labyrinth and exiting through one of the two tiny holes at the top of the flower. During her attempt to squeeze through the tight space, she leaves pollen on the stigma (the flower’s female reproductive organ). She then collects a new bundle of pollen when she passes by one of the anthers (the male organ), which she can carry to the next flower. During this entire ordeal, the fly loses time and energy. It often drops eggs along the way, which are ultimately wasted, as the larvae don’t find the aphids they need to survive.

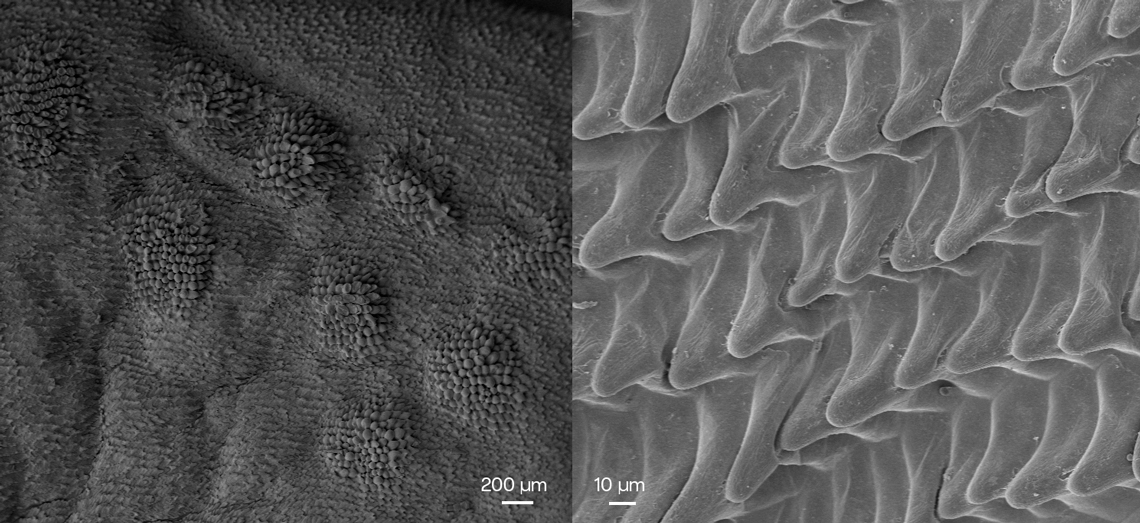

The UFU group also discovered that the plant’s surface tissue, which the fly slips down, is composed of downward-facing, shingle-shaped cells. This characteristic eliminates the flies’ ability to adhere to the flower using the claws on their legs, which hook into rough surfaces. This area of the flower is also covered in mucilage, a viscous substance. Under these conditions, the small adhesive suction cups covering the flies’ legs are unable to attach themselves. “It’s not a singular characteristic that ensures the fly will slip,” explains Cardoso. “The combination of the two circumvents the fly’s adaptations.” The exit path’s surface is lined with trichomes (structures similar to animal fur) on which the fly clings, making it easier to climb out.

Slippery and sticky surfaces are nothing new in trap-flowers and some carnivorous plants, but the finding is unprecedented in orchids. The case of P. vittatum is also unique in that it is the first aphid mimicry reported in the Americas. “This shows that endangered species can hold incredible secrets and should be given the opportunity to be studied,” says the researcher.

A perfect crime?

According to the researchers, it is remarkable that evolution could have resulted in an interaction in which one of the parties receives nothing in return and could even lose their offspring. How could there be such a seemingly perfect interplay between the orchid’s structure and these flies?

João Custódio Cardoso / UFUAn electron microscope allows you to see the embossed effect of the fake aphids (to the left) and a closer view of the slippery shingle-shaped cellsJoão Custódio Cardoso / UFU

Biologist Anselmo Nogueira, of the Federal University of ABC (UFABC), studies how ecological interactions can change the course of plant evolution and explains that there is a temporal bias in the human perspective of these systems. According to him, one must always consider the energy balance inherent to such interactions. Over evolutionary time, systems emerge depending on the balance between costs and benefits, which varies according to the environment’s conditions.

“What we call the conditionality of the interaction’s outcome is a more recent theoretical aspect that is very important for studying ecological interactions, including antagonisms and mutualisms,” he says. “For example, a pollinator may suffer if it spends too much time and energy visiting a flower that prevents it from accessing the floral resource, compared to what would happen with other plant species. This logic only makes sense if there are flowers in the environment with pollen or nectar that are more accessible to the visitor,” continues Nogueira. “In a scarce environment, the relationship may be worthwhile because, despite the energy expenditure, small portions of pollen or nectar could make all the difference,” he says.

In the case of the slipper orchid and the two flower fly species, it’s hard to imagine, initially, that evolution has preserved such costly behavior for the insect, if the females often choose to lay their eggs on the treacherous orchid. The costs, after all, are too high: sacrificing the offspring and, occasionally, death of the adult itself when it fails to pass through the canal. More detailed investigations into the evolutionary significance of the “slipper orchid nursery trick” will require studies about other factors. Namely: analyzing the presence of other plant species used by the flies; the number of times that the same fly falls for the trick before learning from the negative experience and laying its eggs on another surface; the number of eggs lost in relation to the total number of eggs laid by a female.

Scientific article

CARDOSO, J. C. F. et al. The lady’s “slippery” orchid: Functions of the floral trap and aphid mimicry in a hoverfly-pollinated Phragmipedium species in Brazil. Annals of Botany. Vol. 131, no. 2, pp. 275–86. Feb. 1, 2023.