NORMA YAMANOUYE / NATURE PROTOCOLSIn the depths of the Butantan Institute’s main building, in São Paulo, the team led by Dr. Norma Yamanouye is toiling around plates with cylindrical holes, 3 centimeters in diameter, full of a pink liquid. Artificial cherry juice? No, nothing so innocent: the liquid is a nutrients soup – a culture medium, as the biochemists call it – containing poisonous glandular cells of the jararaca snake in full activity. This is the first time that they are producing the jararaca venom in the laboratory, and it was for this reason that the pharmacologist was invited by the international magazine Nature Protocols to demonstrate to the world her innovative technique. Since the 25th of January, any laboratory that wishes to make use of the technique can consult on-line the publication, which brings together the laboratory’s protocols, presented like a recipe for a cake.

NORMA YAMANOUYE / NATURE PROTOCOLSIn the depths of the Butantan Institute’s main building, in São Paulo, the team led by Dr. Norma Yamanouye is toiling around plates with cylindrical holes, 3 centimeters in diameter, full of a pink liquid. Artificial cherry juice? No, nothing so innocent: the liquid is a nutrients soup – a culture medium, as the biochemists call it – containing poisonous glandular cells of the jararaca snake in full activity. This is the first time that they are producing the jararaca venom in the laboratory, and it was for this reason that the pharmacologist was invited by the international magazine Nature Protocols to demonstrate to the world her innovative technique. Since the 25th of January, any laboratory that wishes to make use of the technique can consult on-line the publication, which brings together the laboratory’s protocols, presented like a recipe for a cake.

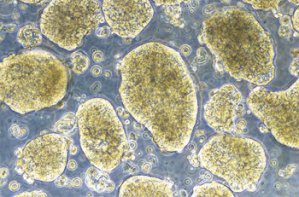

The group has been attempting to cultivate poisonous glandular cells of the jararaca since 2000, but five years were necessary before they discovered the ideal conditions – such as the culture medium – that allows the cells to live and function under artificial conditions. Norma extracted the poisonous glands from the head of a snake and separated out the cells with enzymes, so that they could be spread into the culture medium. Once installed, the cells organize themselves into secretory units of the gland (acinis) and go on to produce venom identical to that of the living snake, which causes, for example, a hemorrhaging effect similar to that observed in the person who receives a jararaca bite.

Norma manages to obtain a good quantity of the venom, but it is still a long way off from being sufficient to produce anti-ophidian serums without which the many bites of the snake would be lethal. Currently, the Butantan Institute maintains reptile stands full of cages more or less the size of this magazine when opened, some 15 centimeters in height. Inside each of them lives a jararaca or another poisonous snake. The poison removed from the snakes kept in the Poisons Sector of the Butantan Institute is the main raw material for producing serum and for treating the around 20,000 accident victims from snake bites that occur each year in Brazil – the majority caused by jararacas. But, for the researcher, to substitute the stands with smaller plates full of liquid is still a distant reality.

Genetic engineering

To produce venom in the laboratory is still more costly than to maintain the snakes in captivity, although it’s a difficult calculation to make. In spite of the high cost of developing laboratory techniques such as this, she believes that the cost will fall rapidly after her team has obtained cultures in which these cells manage to live for some time. Up until this moment, the in vitro glands function, but their cells as yet do not reproduce. For this reason the venom production does not last longer than 21 days, the maximum lifespan of these cells, as the work by pharmacologist Norma has shown up until now.

Once they are able to self divide, the cultures will be durable and will transform themselves into small poison factories. The time may still be far off when the cells will manage to reproduce themselves in vitro. There have been lots of trials and errors in the work on the cell banks and only little by little have they been discovering which reagents are truly necessary to maintain these cells alive and capable of generating new cells.

The advantage is not only in the fact that the pink colored cylinders do not have fangs. In the near future, Norma intends to insert into the cells the genetic material of another snake – the so-called DNA transfection – within the same cells already accustomed to life in plastic receptacles, in order to produce the venom of other species of snakes. This would permit the production of venom of rare snake species for example, at least for research purposes. “Some species are difficult to find in nature, and this limits our knowledge”, she explains.

Norma’s team is also evaluating the possibility of selecting components – toxins – specific to venom that can possibly be of interest to research or for the production of medicines. In this way it would be possible, for example, to produce the specific chemical compound that causes hemorrhaging after a bite from the jararaca. To this end it is necessary to stimulate the genes responsible for producing the desired proteins. The techniques for this genetic manipulation already exist, but as yet, still missing, is the knowledge to make the strategy function with the cells in the culture.

The Project

Molecular and intra-cellular signaling study of the adreno-receptors involved in the synthesis and venom secretion in the venom gland of the serpent Bothrops jararaca (nº 02/00422-8); Modality: Regular Line of Research Assistance; Coordinator: Norma Yamanouye – Butantan Institute; Investment: R$ 297,576.27 (FAPESP)