Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPCesarean sections increase the risk of premature births and the need for neonatal intensive careLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

A Brazilian program to raise awareness and advocate for natural birth among healthcare professionals, hospitals, and expectant mothers has shown promise in reducing unnecessary C-sections in the country. The initiative, called Programa Parto Adequado (“Adequate Childbirth Program,” PPA), was launched in 2014 by the Brazilian Health Agency (ANS) in response to a lawsuit filed by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. The program has so far been implemented in only a small fraction of private hospitals—about 140 out of nearly 4,500—and remains relatively unknown to many pregnant women. However, studies assessing the program’s impact have shown encouraging outcomes.

One such study, published in September in Cadernos de Saúde Pública, was conducted by researchers from the University of São Paulo (USP) and the University of Brasília (UnB). The study compared C-section rates in five private hospitals in São Paulo that had participated in the PPA since its inception with those in 13 private maternity hospitals in the city that had not joined the initiative.

Between 2014 and 2019, these hospitals collectively performed 277,747 deliveries. While C-section rates declined in both groups, the decrease was significantly more pronounced—by 11.5 percentage points—among hospitals participating in the PPA. In these facilities, the rate of surgical births dropped from 83.8% in 2014 to 72.3% in 2019. In contrast, in the 13 hospitals not enrolled in the program, the rate fell only slightly, from 78.9% to 76.2%. Despite this substantial reduction, the proportion of C-sections in PPA-enrolled hospitals remained far above the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended cap of 15%.

In another study, published in 2021 in BMJ Open Quality, Romulo Negrini, head of obstetrics at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein (HIAE), and colleagues evaluated the impact of the PPA on the hospital’s maternity ward. In collaboration with the ANS and the US-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), HIAE helped design the Adequate Childbirth Program and has implemented it since its inception.

As a result, between 2014 and 2019, the hospital’s vaginal birth rate rose from 24% to 30%, while C-sections declined from 76.4% to 70%—the average rate of surgical births in Brazil’s private hospitals remains above 80%. Alongside the increase in vaginal births, the percentage of newborns requiring neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission declined from 19.2% to 13.2%. Unnecessary C-sections can lead to premature births—before 39 weeks of gestation—raising the risk of respiratory infections and neonatal mortality.

“Since implementing the PPA, we’ve seen about 500 fewer C-sections per year at our hospital,” says Negrini. “That may not sound like much, but it’s a major step forward in a country where C-sections are the norm,” he adds.

In a third study, published in September in Reproductive Health, a team led by epidemiologist Maria do Carmo Leal, from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), evaluated which aspects of the PPA were most effective in promoting vaginal birth. Researchers interviewed 2,473 women who gave birth in 12 hospitals across Brazil’s South, Southeast, and Midwest regions. Of the 1,671 women enrolled in the PPA, 37.7% delivered vaginally. This rate was 24.5% among the remaining 802 women.

The likelihood of a vaginal birth, however, reached 80% in hospitals that met four key criteria: they did not preschedule deliveries, they provided expectant mothers with information on best labor practices, they respected the mother’s birth plan, and they allowed women to stay hydrated, move around, use a shower, and access nondrug pain relief methods during labor.

Brazil has long ranked among the countries with the highest C-section rates worldwide. A WHO study analyzing childbirth trends in 154 countries between 2010 and 2018 ranked Brazil second globally, with 55.7% of births performed via C-section—trailing only the Dominican Republic (58.1%). These findings were published in 2021 in BMJ Global Health.

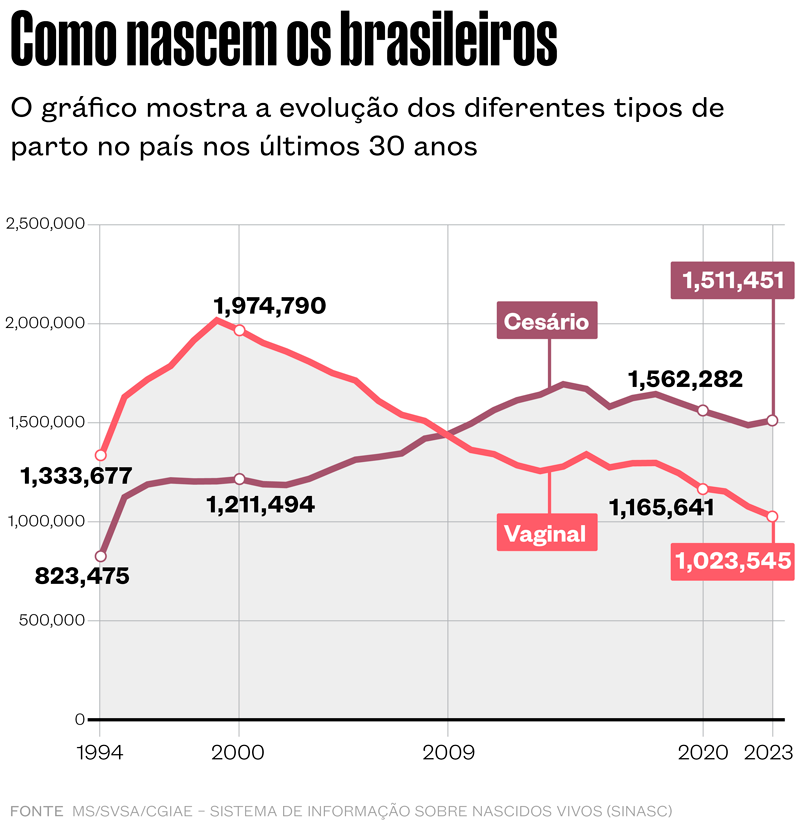

According to Brazil’s Ministry of Health, C-sections have been the predominant mode of birth for at least 15 years. The procedure accounted for 32% of births in 1994, rising to 50% by 2009. Since then, the C-section rate has consistently surpassed that of vaginal births (see chart).

A C-section involves making an incision in the lower abdomen and uterus to deliver the baby. It is, in some circumstances, a necessary and often a life-saving procedure. The benefits of a C-section typically outweigh the risks in cases where the baby is in distress and requires immediate delivery, when the baby is positioned abnormally and cannot descend through the birth canal, or if the mother has active genital herpes. In rarer cases, a C-section is crucial if the placenta detaches prematurely (placental abruption) or if there is uterine rupture.

Yet, when performed without a clear medical indication, C-sections expose both mother and baby to avoidable risks. In Brazil, women without underlying health conditions who undergo C-sections are nearly three times more likely to die from postpartum hemorrhage or anesthesia-related complications than those who give birth vaginally. C-sections also contribute to a higher rate of early-term births, meaning babies delivered at 37 or 38 weeks of gestation—ideally, pregnancy should last between 39 and 41 weeks. Delivering before 39 weeks increases the likelihood of respiratory complications and the need for ICU admission.

Heloisa Bettiol, a retired professor of pediatrics from the Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine at USP, has studied this shift in childbirth patterns over time. Her research covered all births in Ribeirão Preto in 1978, 1994, and 2010. Over this period, C-section rates climbed from 30.3% in 1978 to 50.8% in 1994 and 59.1% in 2010. The increase was most pronounced among women who were more affluent, had higher levels of education, and had access to private healthcare. “We were surprised by the increase in preterm births and low birth weight in this group, as these issues were previously more common in lower-income populations. A major factor was the rise in C-sections, which affected all social groups but was especially pronounced among wealthier women,” explains Bettiol.

The link between excessive C-sections and premature births was further confirmed by pediatrician and epidemiologist Fernando Barros of the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel) in a 2018 study published in BMJ Open. Examining birth records for 2,903,716 babies born in hospitals across 3,157 Brazilian cities in 2015, Barros found that 55% of deliveries were via C-section, and 10% of births were premature. The proportion of births at 37 or 38 weeks was significantly higher (40%) in cities where over 80% of births were by C-section and lower (22%) in cities where fewer than 30% of deliveries were surgical (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 271).

The overuse of C-sections led the nongovernmental organization Parto do Princípio, which advocates for women’s sexual and reproductive rights, to file a civil lawsuit against ANS with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in the early 2010s. In response, in October 2014, ANS, HIAE, and IHI, with support from the Ministry of Health, signed a cooperation agreement to improve the quality of obstetric and neonatal services in hospitals covered by private health insurance, and later launched the PPA.

The aim of the program was to identify innovative and viable models of maternity care to promote vaginal birth as the preferred method of delivery. This would be achieved by creating a coalition of healthcare leaders to ensure quality and safety in childbirth care; empowering women and families to actively participate in pregnancy, labor, and postpartum care; reorganizing maternity care to support the natural progression of labor and ensuring that C-sections were performed only when clinically necessary; and following up on proposed changes.

Pilots were implemented at hospitals and healthcare providers to test interventions, assess results, and share experiences. Training was also provided to equip healthcare professionals with the skills needed to safely perform vaginal deliveries. In the second phase, hospitals from the pilot cycle became reference centers for others. Health insurance providers also added dedicated sections to their websites to inform pregnant women about the PPA program.

The program was first introduced in 2015 and 2016, covering 35 hospitals and 19 health insurance carriers. In the next phase, it expanded to 108 hospitals and 60 health insurance carriers. In 2019, the initiative entered its third phase under a new name, Movimento Parto Adequado (“Adequate Childbirth Movement”), with a goal to achieve further scale. According to ANS, the first two phases of the program helped prevent more than 20,000 unnecessary C-sections across the country.

André Borges / Agência BrasíliaThe PPA program provided training for doctors to safely perform vaginal births and empowered women to actively participate in birth planningAndré Borges / Agência Brasília

Despite the program’s potential, implementation has proven challenging. Another study, published in Reproductive Health by Leal’s team at FIOCRUZ, found that two components of the program’s first phase—engaging women and restructuring maternity care—had low implementation rates. The researchers attributed this to difficulties in bringing about structural and cultural change in private hospitals. “Many women choose to schedule a C-section without realizing it may not be the best option for their baby,” explains Leal. “However, we are beginning to see a shift.”

Moreover, many pregnant women are still unaware of the program, as highlighted in a study by Andreza Pereira Rodrigues, a professor of nursing at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), published in Reproductive Health. After analyzing interviews with 102 pregnant women who received care at two hospitals participating in the PPA, Rodrigues and her colleagues found that most women were unaware of the initiative, and fewer than half had attended prenatal education groups or visited the maternity ward before delivery.

According to Barros, from the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel), better communication is needed to inform women about the risks of unnecessary C-sections. “A continuous public education program is needed, along with reforms in medical training, to challenge the widespread normalization of C-sections,” says Barros.

“C-sections have been associated with a higher risk of chronic health conditions later in life, including diabetes, obesity, asthma, and inflammatory diseases,” adds Carmen Grilo Diniz, a public health specialist at the USP School of Public Health (USP), who led the study on the PPA’s impact on São Paulo’s maternity hospitals.

Despite these risks, gynecologist Andrea Campos, a doctoral student under Diniz and the lead author of the study published in Cadernos de Saúde Pública, notes that there are key reasons why many women prefer C-sections. One major factor is the convenience of scheduling the delivery in advance. Another is the speed of the procedure compared to vaginal birth. “There is a deep-rooted fear of vaginal birth, largely due to historically common but unnecessary interventions—such as episiotomies [surgical incisions in the perineum to widen the birth canal] and forceful delivery maneuvers,” she explains.

Another reason many women opt for C-sections is that the procedure is typically performed by their own obstetrician—the same doctor who provided prenatal care—rather than by hospital staff, midwives, or obstetric nurses on duty. In addition, pressure from family and healthcare providers can strongly influence a woman’s decision about how to give birth.

When nurse Agatha Scarpa informed her family and friends that she had chosen to have a vaginal birth, she faced criticism. Still, she gave birth to both of her children naturally in private hospitals. “I come from a privileged social background, with a university degree in healthcare and the financial means to experience childbirth the way I wanted. That’s not the reality for most Brazilian women,” she explains. “Pregnant women lack access to information about the benefits of vaginal birth and to high-quality prenatal care that helps women feel connected to their chosen maternity facility.”

According to physician and epidemiologist Daphne Rattner, from the University of Brasília (UnB), who coauthored the article in Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Brazil needs a broad obstetric-care reform. “In well-established maternal healthcare systems, low-risk pregnancies are often managed by obstetric nurses or midwives—professionals trained to recognize complications and refer patients to medical doctors when necessary,” she explains. “In Brazil, however, these approaches are met with resistance from the medical community,” she adds.

Experts consulted by Pesquisa FAPESP agree that integrating obstetric nurses and midwives into low-risk childbirth care is key to improving maternal healthcare. Rattner points to Recife as an example of progress in this area. Since 2019, the Recife city government has set up natural birth centers within four municipal maternity hospitals, staffed and managed by obstetric nurses. As a result, the rate of vaginal births attended by obstetric nurses rose from 9.5% in 2019 to 15.5% in 2023. As part of prenatal care, expectant mothers are informed about where they will give birth and are given the opportunity to visit the maternity hospital. “These visits are designed to create a sense of connection with the hospital and include discussion groups and guided tours of the maternity facility,” explains Camila Farias, coordinator of Recife’s Women’s Health Program.

The story above was published with the title “Curbing the overuse of C-sections” in issue 347 of january/2024.

Scientific articles

CAMPOS, A. S. D. Q. et al. Efetividade do Programa Parto Adequado na diminuição das taxas de cesárea de maternidades privadas no município de São Paulo, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, vol. 40, no. 9. 2024.

NEGRINI, R. et al. Strategies to reduce the caesarean section rate in a private hospital and their impact. BMJ Open Quality. aug. 2021.

LEAL, M. do C. et al. The effects of a quality improvement project to reduce caesarean sections in selected private hospitals in Brazil. Reproductive Health. sept. 4, 2024.

BETRAN, A. P. et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: Global and regional estimates. BMJ Global Health. june 2021.

BARROS, F. C. et al. Caesarean sections and the prevalence of preterm and early-term births in Brazil: Secondary analyses of national birth registration. BMJ Open. aug. 1, 2018.

TORRES, J. A. et al. An implementation analysis of a quality improvement project to reduce cesarean section in Brazilian private hospitals. Reproductive Health. apr. 26, 2024.

RODRIGUES, A. P. et al. Women’s voice on changes in childbirth care practices: A qualitative approach to women’s experiences in Brazilian private hospitals participating in the Adequate Childbirth Project. Reproductive Health. jan. 24, 2023.

Republish