“Why do animals go extinct? What is memory? Why isn’t Sunday called Monday?” These are the kinds of questions asked by elementary school students at workshops held by the Children’s University, a science outreach project run by the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). These questions gave biologist Debora d’Ávila Reis, head of the initiative and a professor at UFMG‘s Institute of Biological Sciences, a bright idea. She spoke to Editora UFMG to propose a series of books answering the questions that spark curiosity among children. Thus, the Estraladabão series was born in 2018, featuring 24 titles, all written by academic researchers. The series includes Como se forma a lava dos vulcões (How is lava formed in volcanoes?; 2022), written by Reis, Aracy Alves Martins of the School of Education (FE) at UFMG, and her grandson, Davi, then 8 years old. “Our goal is to talk about science using simple language and elements of literary text,” explains Carla Viana Coscarelli, a professor at the School of Letters (FALE-UFMG) who is head of the publishing house.

Talking about science in a simple way was also what motivated biologist Carlos Navas, from the Department of Physiology at the Institute of Biosciences of the University of São Paulo (USP), to write Sapiência: A surpreendente história de como os sapos falantes descobriram a ciência (Wisdom: The amazing story of how talking frogs discovered science; Instituto Edube). The book, released in October, tells the story of a group of amphibians who are faced with the disappearance of their main food source: flies. In an effort to bring the insects back to the swamp where they live, the frogs start to draw graphs, maps, and tables of collected data to establish hypotheses and make decisions to ensure their own survival. “The public discussion about science during the COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on me. Since then, I have been worried about people’s lack of knowledge about how science is carried out—a process that involves observing, asking questions, and constructing evidence,” says Navas. “That’s where the idea came from to write a book describing the scientific method in a playful way based on topics I study in the laboratory. I think we are lacking this type of content in Brazil, especially for elementary school teachers and students.”

Institutions in the book market, such as the Brazilian Book Chamber and the National Union of Book Publishers, do not have any figures on this segment in the country. Danusa Munford, a biologist from the Center for Human and Natural Sciences at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC), believes there is growing recognition of the importance of this type of content in childhood education in Brazil. “But there is still a lot of room for improvement in curriculums and school reading practices,” adds the researcher, who works in teacher training and studies the science learning process in the initial years of elementary school. “Reading these books with the mediation of teachers brings children closer to science; they use common elements of children’s literature such as illustrations and humor and can be linked to scientific research projects in the classroom. We must not forget that it is at school that most children come into contact with books.”

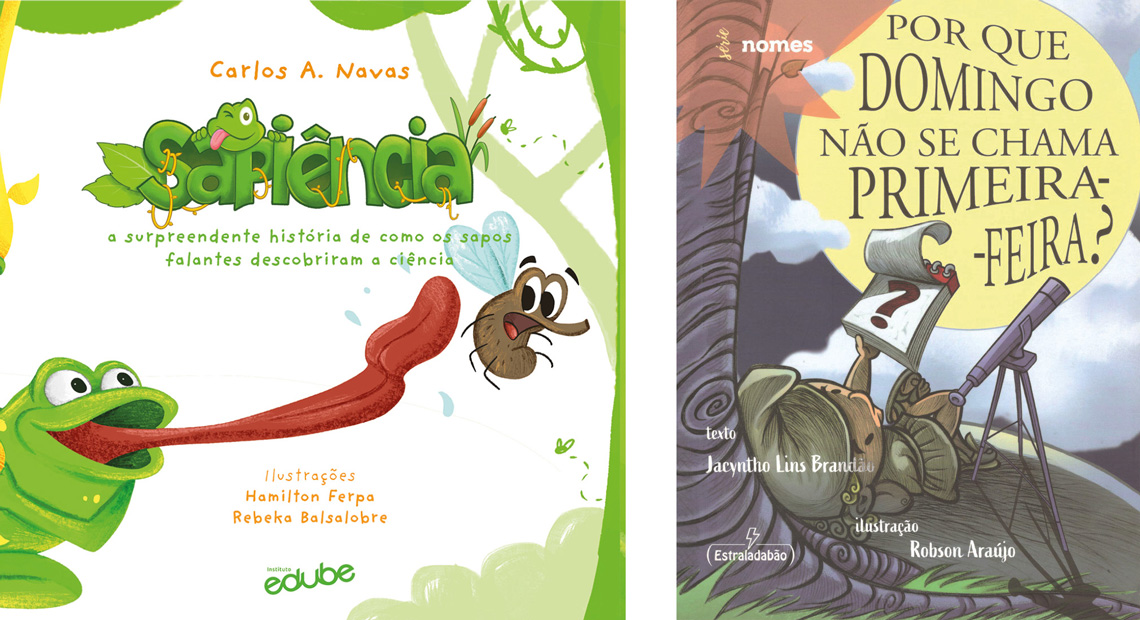

Publicity / Instituto Edube | Publicity / Editora UFMGBook covers by USP biologist Carlos Navas and Jacyntho Lins Brandão, professor of Greek literature at UFMGPublicity / Instituto Edube | Publicity / Editora UFMG

In 2024, the National Textbook Program (PNLD), an initiative of the National Fund for the Development of Education (FNDE) and the Brazilian Ministry of Education, which is responsible for assessing and selecting which books will be taught in public schools, added an “informative book” category. The term is in line with the nomenclature used in the USA and Europe, which also define this type of content as nonfiction. “It is a more comprehensive designation than ‘scientific communication,’ which is often associated with the so-called hard sciences. For example, it includes books related to the humanities and social sciences,” explains librarian and pedagogue Marcus Vinicius Rodrigues Martins, who analyzed 80 informative children’s books written in Portuguese, Spanish, French, and English during his PhD, defended at FE-UFMG in 2020. “Since the turn of this century in particular, this type of work has been appropriating the graphic and literary resources of children’s fiction. By combining literature, science, and art, informative books contribute to both scientific education and aesthetic development.”

Paleontologist Luiz Eduardo Anelli, from USP’s Geology Institute, agrees about the importance of these resources. “I tell stories about dinosaurs and other topics, always following scientific criteria, but with the support of illustrations and metaphors. The challenge is not to underestimate the intelligence of the readers and to attract their attention in a world that is increasingly dominated by screens,” says the researcher, who published his debut book in the segment in 2008 with Guia dos dinossauros do Brasil (Guide to the dinosaurs of Brazil; Editora Peirópolis). He has since published 21 books and currently has two more in production. This year, his book ABCDarqueologia (ABCDarcheology; Editora Peirópolis, 2023), coauthored by Celina Bodenmüller, won the 1st Academic Jabuti Award for its illustrations, drawn by Graziella Mattar. “Today, I consider myself a writer who studied paleontology,” says Anelli with a laugh.

Children’s books written by scientists are not new in Brazil. “These types of books have been circulating in the country since the nineteenth century through the translation of titles originating mainly from France,” says Kaori Kodama, a science historian from Casa de Oswaldo Cruz at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (COC-FIOCRUZ). One such author was the physician and chemist Louis Figuier (1819–1894), who abandoned his scientific career to write articles for the press and books, including for children. “In Brazilian schools, the best students were awarded with works by Figuier,” continues Kodama.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Brazilian biologist and zoologist Rodolpho von Ihering (1883–1939), who worked at the Paulista Museum, among other places, published such titles for children as Férias no pontal (Holidays at Pontal; 1924), which was re-released by Livros Vivos in 2024. Another researcher who ventured into this field was bacteriologist José Reis (1907–2002), from the Biological Institute of São Paulo, known for his pioneering work in scientific communication in Brazil. According to the book José Reis: Reflexões sobre a divulgação científica (José Reis: Reflections on scientific communication; FIOCRUZ/COC, 2018), edited by Luisa Massarani and Eliane Monteiro de Santana Dias, he wrote books such as Aventuras no mundo da ciência (Adventures in the world of science; 1950), which takes place in a scientific institute and addresses aspects of natural history. For Navas, from USP, writing for this audience is something of a two-way street: “The feedback I’ve been getting from children is influencing the questions I ask as a scientist,” he says.

The story above was published with the title “In the language of children” in issue 346 of December/2024.

Republish