COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTH

Physician Astrogildo Machado (seated with fingers interlocked) in the Tocantins Valley at the end of 1911COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTHIn March 1912, physicians Arthur Neiva and Belisário Penna, scientists from the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, left their laboratories and headed to Salvador, Bahia, from where they journeyed into the wilderness of the states of Pernambuco, Piauí, and Goiás. Traveling by packet boat and steam train, on horses and mules, they proceeded through little-known regions, assessing the health conditions of local populations and the occurrence of infectious diseases. At the same time, they documented the geographic, economic, and socio-cultural features of the places they visited. Their records from the expedition resulted in a chronicle of rural living conditions, habits, and perspectives, and

their photos and journals had great repercussions among the Brazilian medical and intellectual elite, revealing a diseased, exploited, and uncivilized side of Brazil living outside the cosmopolitanism of the major cities.

The expedition led by Neiva and Penna came in the wake of other scientific journeys undertaken in the early twentieth century by order of government agencies and private companies. The objective was to explore the economic potential of the Brazilian territory, promoting national integration by developing even the farthest reaches of the country. In 1906, physician Antônio Cardoso Fontes (1879–1943) had been sent to São Luís, Maranhão, to contain an outbreak of the bubonic plague, while Carlos Chagas (1879–1934) implemented Brazil’s first campaign against malaria in Itatinga, São Paulo, where Companhia Docas de Santos was planning to build a hydroelectric plant. The following year, alongside Arthur Neiva (1880–1943), Chagas also led an attempt to eradicate malaria in Xerém, Baixada Fluminense, where the Public Works Department was capturing water to supply the city of Rio de Janeiro.

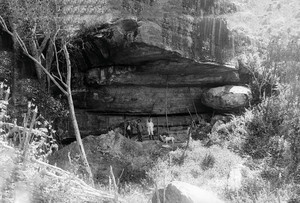

COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTH

Entrance to the cave in Lassance, Minas Gerais, where Carlos Chagas found and collected Triatominae, the vectors of Chagas diseaseCOC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTHChagas also joined Belisário Penna (1868–1939) in Minas Gerais in 1907 to contain a malaria outbreak that was hindering extension works on the Brazilian Central Railroad. A few years later, in 1910, physician and public health expert Oswaldo Cruz (1872–1917) conducted inspections near the construction site of the Light and Power hydroelectric plant in Ribeirão das Lages, Rio de Janeiro.

Scientific expeditions undertaken by the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (now the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) between 1911 and 1913 were instigated by the same demands. Between September 1911 and February 1912, physician Astrogildo Machado (1885–1945) and pharmacist Antônio Martins traveled through the São Francisco and Tocantins valleys with the Brazilian Central Railroad teams. Carlos Chagas, Pacheco Leão (1872–1931), and João Pedro de Albuquerque (1874–1934) were also sent on an important expedition by the Rubber Defense Authority from October 1912 to March 1913. “Contracted expeditions were nothing new to the researchers from Manguinhos,” explains historian Fernando Pires-Alves, from the Department of Research into the History of Science and Health at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation’s Casa Oswaldo Cruz (COC-FIOCRUZ). “Many had already conducted disease inspections and implemented anti-disease measures at the construction sites of railroads, dams, and ports along the Brazilian coast.”

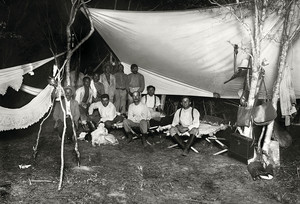

COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTH

Belisário Penna and photographer José Teixeira shortly before setting off for Bahia in 1912COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTHHowever, no expedition had quite such an impact as the one led by Neiva and Penna, who wanted to observe and map the incidence of diseases in the north of Bahia, southwest of Pernambuco, south of Piauí, and north and south of Goiás. The scientists traveled these regions between April and October of 1912, often sleeping in improvised tents in the middle of the forest. They studied the living conditions and history of the places they visited to gain a better understanding of the incidence and distribution of certain diseases, and to propose prophylactic measures to combat them. “Neiva and Penna’s expedition stands out because of their highly detailed observations, the testimonies of the locals, and the vast photographic record of how people lived in rural Brazil,” says historian Dominichi Miranda de Sá, also from the COC-FIOCRUZ Department of Research into the History of Science and Health.

Approximately 1,700 photographs were taken by the group’s photographer, José Teixeira. Some of them have been recovered and are now stored in the COC-FIOCRUZ Archive and Documentation Department, alongside the journals and reports written by the scientists. The records indicate that rural populations suffered such diseases as malaria, tuberculosis, syphilis, leishmaniasis, leprosy, and yaws (a dermatological disease). There were frequent cases of diphtheria and anthrax—a skin infection that usually affects the neck and back. The scientists were greatly interested in the previously unseen diseases they encountered, such as “entalação” and “vexame.”

COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTH

A village in Paripi, Amazonas, one of the regions visited by the researchers in 1912COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTHThose suffering from entalação “caused irrepressible laughter when, in tragic but comical convulsions and gymnastics, they attempted in vain to swallow their food, sometimes unable to eat for two or three days,” the doctors wrote in their travel journal. Vexame mostly affected women, triggering “a silent attack, with no contortions or convulsions of any kind. If the patient is standing at the time, they fall over—if they are sitting down, they remain seated—unable to speak or move, but usually hearing and seeing everything going on around them, and remaining in this state of immobility for anywhere from ten minutes to an hour.” These conditions were later identified as clinical manifestations of Chagas disease.

COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTH

Neiva and Penna (center, seated) at their camp in Bebe Mijo, Piauí, in 1912COC-FIOCRUZ DEPARTMENT OF RESEARCH INTO THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND HEALTHThe researchers also observed local healing practices. One remedy for people bitten by rabid dogs—known as being “gutted” in the local vernacular—involved a mixture of garlic, salt, and urine, as well as putting in the patient’s mouth the key to the church’s tabernacle. For cases of diphtheria, patients were given lemon and the left canine tooth of a wild pig, which was roasted and then diluted with alcohol. The scientists observed the lifestyles of isolated communities in Porto Nacional and Goiás: “(…) men of the forest who speak little, hear a lot, and silently decipher the signs of nature, interpreting when to sow and when to reap.” Unlike the wilderness of Piauí, there were almost no cattle, horses, or mules in Porto Nacional and Goiás. Tobacco only grew on fertilized land and corn only yielded one or two ears. No currency was exchanged, and all food was obtained by bargaining.

“Rare is the individual who truly knows Brazil,” wrote Neiva in one of his notes. “For these outsiders, the government is a man who tells people what to do, and they only know of its existence because this man comes to charge them taxes every year,” said the scientists. The reports by Neiva and Penna were published in the Oswaldo Cruz Institute’s Memórias Journal in 1916. They portrayed a vast wilderness with low demographic density and high rates of illiteracy, where there were few—if any—means of transportation and communication with the coast. “The reports also highlighted a lack of doctors, as well as poverty, apathy, disregard for the law, and violent conflict resolution,” says Sá.

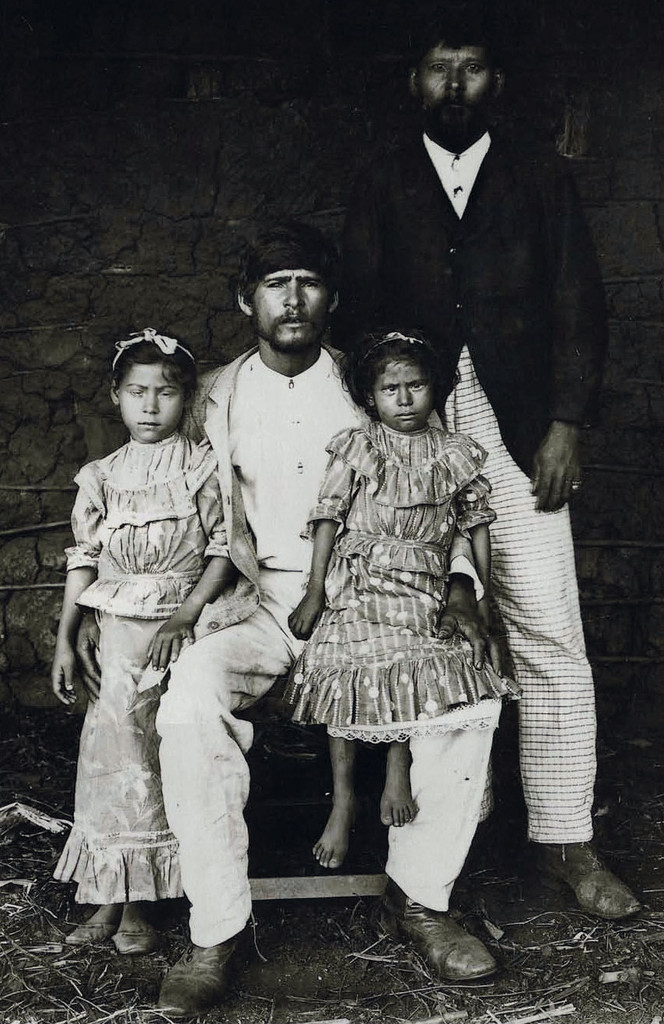

REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK A CIÊNCIA A CAMINHO DA ROÇA

Adults and children in Caracol, Piauí, were frequently affected by conjunctivitisREPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK A CIÊNCIA A CAMINHO DA ROÇAShe believes the writings strongly influenced public opinion in the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo through columns and articles published in newspapers such as Correio da Manhã. After the expedition, Neiva and Penna became relentless advocates for Brazilian public health, trying to persuade political leaders that the country would only see economic, social, and moral progress with improved conditions for rural populations. Several writers were influenced by their reports, including Monteiro Lobato (1882–1948), who joined the campaign for national health awareness. After reading the reports, Lobato publicly revised his conceptions of Jeca Tatu, a character from the countryside who became a symbol of rural Brazil after featuring in his short story “Urupês,” from the book of the same name, published in 1918. “Jeca ceased to be seen as a problem, as lazy and idle in a country that offered him everything he could wish for, and became a sick man abandoned by the powers that be,” says Pires-Alves.

The travel reports also contributed to the emergence of the Brazilian Public Health Movement in February 1918, and the creation of rural health clinics in several states around the country. “The informative and documentary value of the images and travel journals produced by the Oswaldo Cruz Institute’s scientific expeditions have an undeniable historical reach, contributing to a deeper knowledge of Brazilian society,” says sociologist Nísia Trindade Lima, president of FIOCRUZ and author of the book Um Sertão Chamado Brasil (A wilderness called Brazil).

Republish