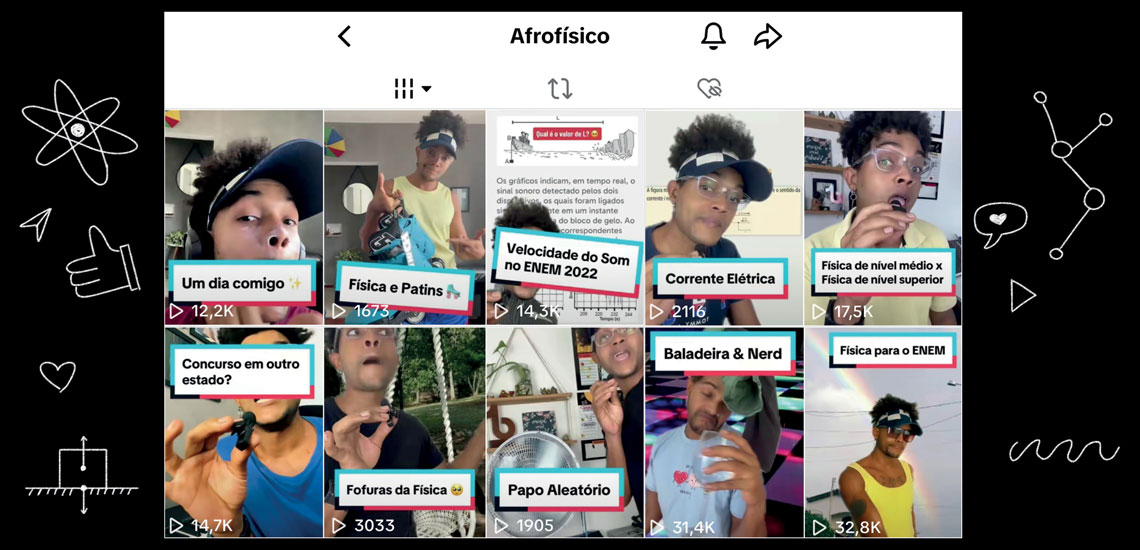

“Wait, is that a convex mirror? It’s a virtual image, it’s smaller, and upright, correct?” asks physicist Alexandre Rodrigues Barbosa, 31, in a video in which he portrays a student learning physics concepts for the National High School Exam (ENEM), who keeps noticing physics in the details of everyday life. Dressed in shorts and a tank top, he moves through scenes that are constantly changing thanks to a green screen (chroma key) background, a common technique used by TikTok video creators that allows locations or objects to be inserted as background scenes, while the narrator appears in the foreground. Barbosa uses this artifice to display the image of a rainbow as he explains the phenomenon’s physics—and several other physics concepts—in one of his videos. Just over a minute long, the video currently has accumulated 32,500 views.

Barbosa completed his doctorate in June at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) School of Education, with research on the creation of online science content, and shortly thereafter became a professor at the same institution. On social media, he uses the name Afrofísico (“Afrophysicist”), a profile he created in 2021, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, after trying to post his videos on YouTube but not getting many views. “I wasn’t teaching classes yet and I wanted to talk about physics concepts in a lighthearted, fun way,” says Barbosa, who has 107,900 followers on TikTok and 35,000 on Instagram.

The physicist is part of a team of students, postgraduates, and young teachers who, since the pandemic, have routinely made a practice of getting in front of their smartphones and recording videos (one and a half minutes long, on average) on a wide range of science topics—including curiosities about the academic world—for a broad and equally young audience. On their own time, they create paintings, write scripts, play characters, and edit videos on their smartphones, publishing them for their thousands of followers on short-video social platforms. Because they have already created their own virtual communities, they are invited to lecture at universities, and receive offers from companies to make “advertorials;” paid content that helps supplement their income.

According to data from the firm Insider Intelligence, the networks that grew their user numbers most in 2022 in Latin America were Tiktok (11.8%) and Instagram (3.2%). In Brazil, Instagram had 113.5 million users and TikTok had around 82 million as of early 2023, according to data compiled by the website DataReportal, which gathers information on advertising from technology companies. The majority of content creators publishing short science videos began their activities during the pandemic, motivated by the desire to combat disinformation and the possibility of using their free time at home to disseminate science. “During the pandemic, more people started talking about science on social media. As TikTok became popular during this period, many science publishers started using it and Instagram, which also created a short video format, ‘Reels,’” observes Barbosa.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp

Carlos Stênio: a series of videos that combine biology and pop culture was the thesis of his master’s degree at UNICAMPLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FapespSuch was the case for biologist Carlos Stênio, 28, who is studying for a master’s degree in Earth science pedagogy and history at the Geosciences Institute of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). In 2020, he began occasionally posting short videos on Instagram about pop culture and biology—which would later become the subject of his graduate school research. At the time, Stênio was in graduate school and had just lost his job selling industrial paints. “I received a contact from TikTok encouraging me—and other colleagues in the field—to participate in campaigns producing educational and science videos there,” he says. He says the platform paid in accordance with the number of videos posted. “With one campaign I earned the equivalent of six months’ work—before, as a salesperson, I was earning minimum wage,” he recalls.

Since then, he’s opted to dedicate himself to producing content for social media. When contacted by Pesquisa FAPESP, the TikTok network did not state what actions it promotes to encourage this type of content. Others interviewed for this report confirmed that they had been invited to lectures and workshops, and to participate in campaigns for the platform. In one of his videos, which has accumulated 5.9 million views and more than 4,000 comments on TikTok, Stênio shows two caterpillars, one green and the other orange, of the species spicebush swallowtail (Papilio troilus, also known as the eastern tiger), both of which feature spots on their bodies that look like eyes. Then he reveals that they were the inspiration for Caterpie, a character from the Pokémon universe. Other pop culture icons such as SpongeBob, Ice Age, and Spider-Man also appear in his videos to illustrate the real-life biology behind the characters.

He posts frequently for his 232,700 TikTok and 100,000 Instagram followers: seven videos per week, one per day. The same production goes to both platforms. He writes the scripts during the week and records everything for all the posts on Sundays, editing them on his smartphone, unless it’s a paid advertising post, in which case he hires a freelance editor to finalize the content. “I’ve already been approached to promote animated films for HBO, Disney, and Netflix,” Stênio says.

Like Barbosa, who has previously refused advertising because he didn’t feel comfortable recommending certain products, Stênio only accepts offers that have some connection with his work as a science communicator. The biologist adds that the income earned through his visibility on social networks—including from the monetization of videos and the column he maintains on the Vida de Bicho website, and earnings from the Globo network and the sale of books and e-books he’s written during this period—now amounts to half his monthly income. “I intend to be a university professor and researcher, but I want to continue with science communication work,” he says.

Biologist Eduarda Melo, 26 years old, says that working on social media is already her primary source of income. She learned to enjoy informal and audiovisual education while creating videos during her undergraduate studies at Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in Niterói (RJ). Her first video, about the evolutionary proximity of bears and seals, was published at the end of 2022 on TikTok, Instagram, and Shorts—a kind of Reels—on YouTube. Her current follower count is 334,000, 104,000, and 370,000, respectively, on these three social networks, where she is known as the “Biologueirinha.”

Melo had previously been working as an environmental educator at a company, but she was unsatisfied. “I wasn’t registered as a biologist, I was paid minimum wage, and I didn’t see any prospects for future growth,” she recalls. In April, she gave notice. With more free time, she started recording videos again. “My third video hit 2 million views in two days on TikTok. In the month after leaving my job, I earned more than double my previous salary,” she says, referring to the amount the platform paid her based on the volume of views. Today, she dedicates all her time to creating content and her income comes from monetizing her videos on YouTube, in addition to the advertising she does for companies.

In her video creations, she talks about curiosities of the animal world—her followers’ most frequently requested topic—while photos, animal videos, and words are superimposed in the middle of the screen. She also uses certain memes, such as the song Careless whisper, by British singer George Michael (1963–2016), which plays every time she talks about reproduction, a common joke meme among the social network’s users for topics related to romance and seduction. Melo takes up to six hours to research and write a script for one of her videos, which are up to 3 minutes long. She edits all of them herself and tries to post at least three per week. She says she would like to post even more frequently but is unable to do so due to the complexity of producing the scripts. Her principal audience is between 18 and 26 years old.

Image: Tik Tok | Illustrations: Vitória Couto

The similarity between the Pokémon Caterpie and real caterpillars in a video by Carlos Stênio; and Juliana Moraes, the @meninadospassarinhos: experience making videos at university led her to Instagram and TikTokImage: Tik Tok | Illustrations: Vitória CoutoThe appeal that animals have with social media audiences also helps explain the success of the videos produced by biologist Juliana Moraes, 26, who is working towards her doctorate at the Ecology Program at UFBA, in Salvador. In her creations, the birds are the stars. During her undergraduate and master’s degree studies at UFBA, she studied the behavior of burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia). Moraes enjoyed talking to the public during her internship as an environmental educator and began investing in creating videos. In 2020, she participated in a science communication contest put on by the university in which she needed to explain her final graduation project in a video up to 3 minutes long. “I recorded it and posted it on TikTok, where it was easier to edit,” says Moraes, who won in the undergraduate research category. “After that, I lost my embarrassment and never looked back,” says the researcher, who has 53,500 followers on TikTok and 79,900 on Instagram where she presents herself as @meninadospassarinhos (the bird girl). “These science communication activities were valuable points in the selection process for my doctorate,” she remembers.

The biologist has noticed that audiences differ depending on the platform: on TikTok, there are more teenagers and young adults, from the ages of 16 to 23; on Instagram, the primary audience is from 25 to 30 years old. Her audience follows her behind the scenes while doing her fieldwork and sees tips on how to enroll in a master’s program, in addition to the videos in which she comments on other videos that have gone viral on the platform demonstrating peculiar bird behaviors or situations. In one of them, which has 1.2 million views on TikTok, she shows what the bird characters in a Disney animation look like in reality. On average, it takes 50 minutes to edit each video of just over a minute in length.

In another video, made at the request of her followers, she comments on a recording in which a person picks up then caresses a burrowing owl, and places it close to its nest, and explains that, because it is a wild animal, the person’s behavior is not appropriate—beyond which, the animal was visibly scared and stressed. One of her priorities is responding to her followers’ requests. “There’s no point in wanting to make content about the things that only I find interesting,” says Moraes, who does the occasional ad—such as for a brand of t-shirts for birdwatchers—and who has already been a target of haters (people who spew hatefulness in comments on the internet). “The most striking were xenophobic attacks that complained about my Salvador accent. Today I make an even greater point of emphasizing it. I’m proud to be a woman, a Northeasterner, a scientist, and a science popularizer.”

Image: Tik Tok | Illustrations: Vitória Couto

Biologist Eduarda Melo, the “biologueirinha,” and the historian couple Julia and Jerson analyzing the film NapoleonImage: Tik Tok | Illustrations: Vitória CoutoHistory and public health

The opportunity to share research of interest to the general public that connects with their daily lives motivated historians Jerson de Oliveira Fernandes Filho, 26, and Júlia Costa da Silva Pedroso, 25, to create the “Gole de História” (Swig of history) channel on social media in 2021. Fernandes Filho is studying for a master’s degree in history at UFF, and Pedroso has a degree from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. In addition to working on the digital platforms, the two also give private classes. They started with a half-hour video explaining certain historical curiosities behind the video game Assassin’s Creed: Pirates, a franchise known for its well-grounded adaptations. “It didn’t work out very well, we had a low number of views and felt that, at that moment, the internet was heading in another direction: videos lasting just a few seconds or minutes,” says Fernandes Filho. A friend then suggested they try TikTok.

Today they have 67,700 followers on that platform and 13,500 on Instagram. It took a while for them to understand what types of videos did well on these social networks. They try to make dynamic productions, including images of documents, and fun facts about films, museums, and songs that allow them to address a historical context. “We need to get out of the ivory tower and put on our public historian hats. After all, what academic article has 100,000 or 200,000 views, numbers we’ve reached in some of our videos?” the historian asks. “We have already received photos from three followers who were already pledging colleges, who said that seeing our work helped them decide to major in history,” says Pedroso.

The couple has already done advertising for institutions and brands—Fernandes Filho says this work, along with the monetization of videos, became the principal source of their household income a few months ago. The couple also says that the education company where they teach private classes considered their activities as science communicators on the social networks as a positive factor in the hiring process. “It is a third path that’s opened up in our career, in addition to research and teaching,” observes the historian.

Fernandes Filho defends the importance of science communicators’ work. “Young students are increasingly using social networks to do school research or find knowledge to complement their classes. So it’s better that people who are doing serious work occupy these spaces,” he says, emphasizing that otherwise, the platforms’ algorithms would lead users to content from poorly prepared science promoters and even those who spread disinformation. Barbosa, from UFBA, is also concerned about biases in the algorithms themselves. In his doctoral thesis, he reflected on the dilemmas that publishers face by being held hostage to the platforms’ audience. “Science on social media is influenced by the dynamics of algorithms. The content needs to attract attention and have entertaining elements so that the science message will spread. You have to be careful not to deviate from this focus, and produce quality videos,” he adds.

The fight against disinformation permeates the work of biomedical researcher and neuroscientist Mellanie Fontes-Dutra, 31, from Sinos River Valley University (UNISINOS), in São Leopoldo (RS). Since 2021, she has made a routine of sitting down with her smartphone every other day to record videos on public health topics and combating disinformation. In one of them, made in early November 2023, she declares, right off the top: “No, guys, the Canadian government did not say that vaccinated people are contracting AIDS.” Featured words, news snippets, and graphics dance across the screen to make the piece more dynamic. She does all the editing herself.

Dutra refuted disinformation that was circulating on social media that people who were vaccinated against COVID-19 were contracting HIV. In her video, she explains what was behind the confusion, and the real modes of infection. “Health misinformation can kill. Fighting it has become a necessity during the pandemic. But it still continues to circulate,” says Dutra, who balances creating videos with teaching classes at UNISINOS and her postdoctoral internship work in virology at Feevale University. Despite having already dedicated herself to popularizing science since 2015—she coordinates the scientific communication event “Pint of Science” in Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul—and sharing her analyses and explanations on X (previously Twitter), in 2021 Dutra saw a need to move to social networks that bring together a younger audience, where short videos are the main attraction.

In October 2023, her posts reached 160,000 people on Instagram, where she has 27,900 followers; on TikTok she has 1,380, and her videos have had 7000 views. In her content she clarifies communications and news from health institutions that may raise doubts and can be an abundant source for disinformation content. She also posts in collaboration with other colleagues and is part of the Todos pelas Vacinas health collective, which ran a series of campaigns during the pandemic and continues to bring together other science communicators to reinforce the importance of vaccination. She has even created ads for a company that uses DNA for ancestry analysis, and for a house rental agency, but these are only occasional opportunities. “Our work is often voluntary and needs to be professionalized. It’s important that there be initiatives and public funding to help give it value,” the neuroscientist argues. The audience that influencers like Dutra have reached suggests that short videos can be another tool to bring society closer to science issues.

Initiatives are emerging that encourage the production of quality short videos, among other science communication activities. One, called Communicating Science, launched by FAPESP in partnership with the Roberto Marinho Foundation’s Canal Futura, will offer six-month science journalism scholarships to undergraduate students linked to institutions in the state of São Paulo, to conduct science communication for projects supported by FAPESP. Submissions can be entered until January 22, 2024. Students will choose one of four formats for their productions: podcast, video report, written report, or producing short videos 2 to 5 minutes in length for social media. “The idea is to train students in new formats—like those on social networks that are more in vogue, such as TikTok and Instagram—short videos that reach young audiences,” explains Patricia Tambourgi, who manages the Communicating Science initiative and the FAPESP Science Journalism Program. Scholarship recipients will have access to an online course on multimedia production techniques, offered by Canal Futura.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp

Kiko Mistrorigo with the educational books featuring the character LunaLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FapespA science popularization animation for early childhood, O show da Luna, which will complete its 10th season on the air in 2024, will debut in the educational materials format, in the form of books for early childhood education (4- and 5-year-olds) and elementary education (1st and 2nd grade). “The idea is that the material will help teachers with students’ scientific literacy using fun, playful content,” explains Kiko Mistrorigo, creator and director of the animation, with Célia Catunda. “When we created the series, the protagonists of science cartoons were always boys, while girls had a secondary role. That’s why we made Luna the main character in the cartoon,” he adds.

Topics such as the lives of dinosaurs, the water cycle, or why colors mix are some of the questions the 6-year-old character asks in the episodes. “The books follow the same strategy of bringing thought-provoking questions to children,” says Mistrorigo. He expects the books will soon begin arriving at certain municipal schools in the state of São Paulo, which purchased the material at the beginning of the year. The cartoon also has channels on YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram and is programmed on the Discovery Kids cable channel, as well as the TV Cultura and TV Brasil broadcast networks.