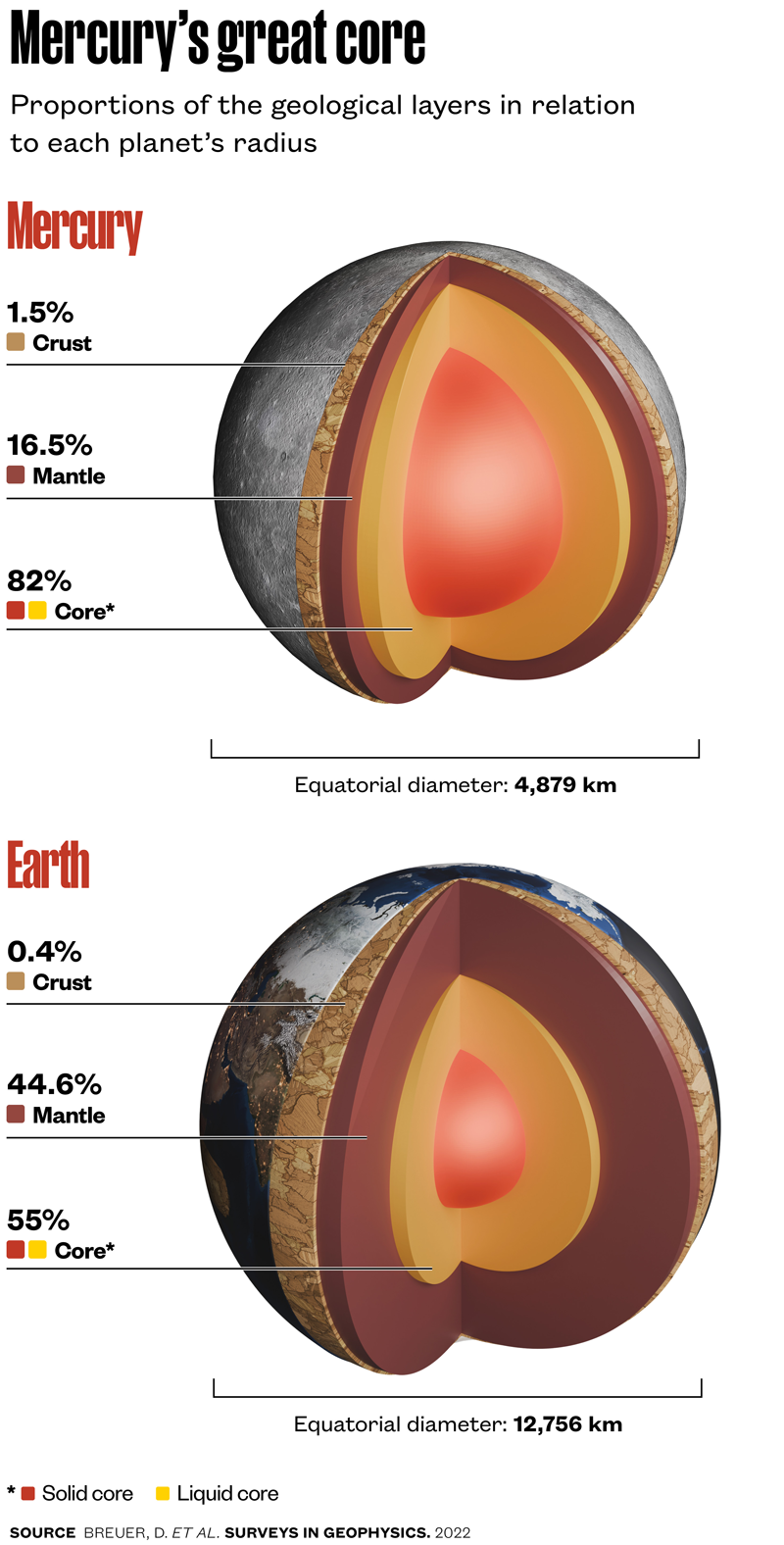

One of the challenges for the models attempting to unravel the processes that shaped Mercury, the smallest planet in the Solar System, is finding a plausible scenario capable of explaining a unique aspect of its geology. Mercury’s core, the innermost layer of its structure, is proportionally much larger than that of Earth, Venus, or Mars, the other three rocky planets in the Solar System. Due to this characteristic, the size of its mantle, the intermediate layer between the core and the outer crust, is relatively small compared to that of the other rocky planets. This feature has led astrophysicists to speculate that Mercury experienced some sort of major impact that altered its geological structure.

A study coordinated by Brazilians proposes a variation of this model to explain the genesis of Mercury and its extensive core, which accounts for over 80% of its radius. According to the article, available as a preprint on the arXiv repository and accepted for publication in a scientific journal, the planet’s composition was altered in the early days of the Solar System as a result of a major impact, albeit a glancing one, that tore away a portion of it. “Our computer simulations suggest that the current geological structure of Mercury could have been the result of a hit-and-run-type collision,” says Brazilian astrophysicist Patrick Franco, who is doing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Institut de Physique du Globe in Paris, France, and lead author of the study.

Similar to a reckless driver who runs somebody over in the street and flees the scene of the crime, a hit-and-run-style space accident involves a celestial object striking another, potentially causing damage to both. In this hypothetical celestial collision, Mercury plays the role of the reckless driver, according to the study.

“Attributing the planet’s geological structure to a hit-and-run-type scenario is nothing new. Other studies have already done so,” explains astrophysicist Fernando Roig, of the National Observatory in Rio de Janeiro, who is also a coauthor of the paper and was the advisor for Franco’s PhD thesis on Mercury’s formation, defended in 2023 at the same institution. “These previous studies said that Mercury must have collided with a larger object. But our simulations indicate that collisions between bodies of very different sizes are rare. The results suggest that the most likely scenario is a collision between the planet and an object of similar size.” Researchers from São Paulo State University’s (UNESP) Guaratinguetá campus, and from French and German institutions are also among the coauthors of the work.

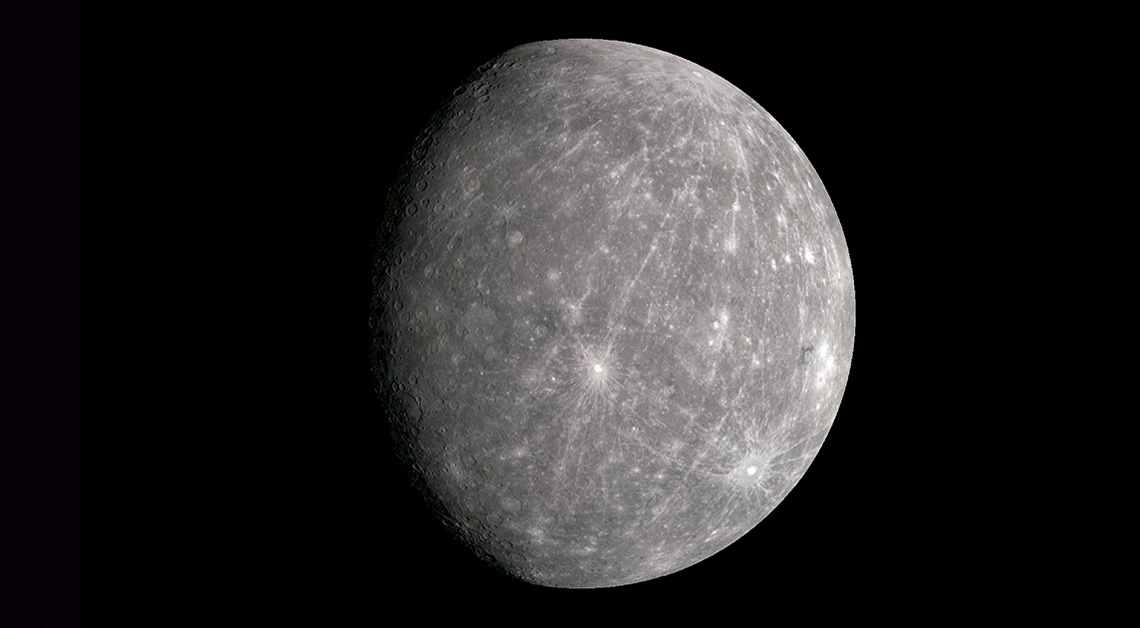

Not just any celestial collision would have the power to create an object with Mercury’s main characteristics. The innermost planet in the Solar System appears to have formed under extremely special conditions that led to its peculiar features. Starting with its size. It is small and dense. Its diameter is 38% that of Earth’s, and its mass is equivalent to just 5.5% of our planet’s.

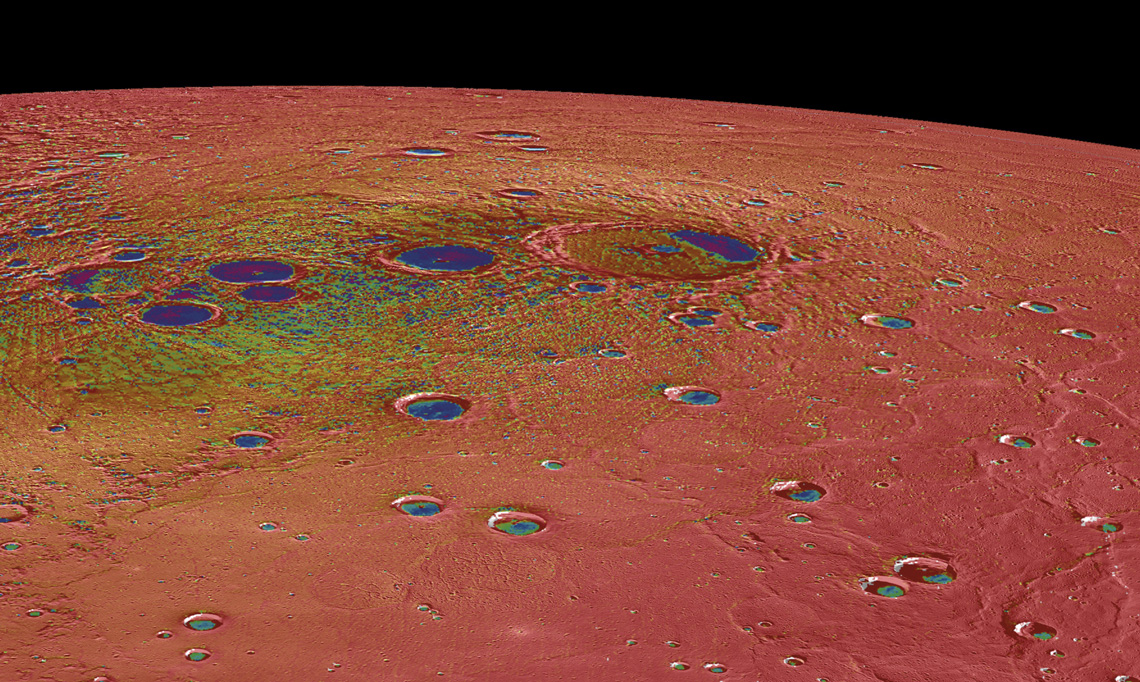

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Carnegie Institution of WashingtonA colorized image of Mercury’s north pole during a moment of great temperature variation, with red areas surpassing 200 ºC and blue regions reaching only 10 ºCNASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Carnegie Institution of Washington

In addition to size and density, the simulations also had to try to replicate Mercury’s internal structure, which is made up of 70% iron, mostly in the core, and just 30% silicates—a silicon-based compound, widely found in different forms in nature, such as rocks, clays, and minerals. “We found a scenario in our simulations in which a glancing collision with a similar body results in a rocky protoplanet having a geological composition and mass similar to Mercury’s, within a 5% margin of variation,” explains Othon Winter from UNESP, a collaborator on the study.

In the simulations, the best results were obtained when the collision between the celestial body and proto-Mercury did not occur head on, but at a 32-degree angle and at a relatively low impact speed of 22 kilometers per second. It was estimated that, in its early stages, Mercury had a little over twice its current mass, while the other body was slightly larger still. The planet was simulated with an initial composition of 70% silicates and 30% iron, more or less the reverse of its current makeup. This entire scenario was created using a computer model that replicates conditions similar to those of the early Solar System, around 4.5 billion years ago.

“We ran three rounds of collision simulations, altering these critical parameters: the mass of both bodies, their relative speed, and the angle of impact,” says Franco. “Although we have not ruled out the possibility that Mercury experienced more than one collision, we were able to explain its geological composition with just one.” The angled collision would have been strong and caused Mercury to lose a significant part of its mantle, where silicates are mostly found, with minimal alteration to its iron-rich core.

About 48 hours after the collision simulations, Mercury would have already taken on a relatively stable and similar configuration to its current one, with an enlarged core and reduced mantle. For comparison, Earth is the terrestrial planet with the largest core relative to its radius, after Mercury. Earth’s core spans 55% of its diameter and is, proportionally, about one-third smaller than Mercury’s.

Studies on the origin of Mercury are only possible because today, despite there still being knowledge gaps, astrophysicists have a good understanding of how rocky planets form. Because they are closer to the Sun, they form from the gradual accumulation of dust and gas released by the disk of matter that created the star. Rich in carbon and iron, the dust clumps together, initially forming small rocks. Over time, due to gravitational interactions and other forces, the rocks collide with one another.