Skaman306 / Getty imagesIn 40% of cases, sedatives, epilepsy and Parkinson’s medications, or other psychotropic drugs were usedSkaman306 / Getty images

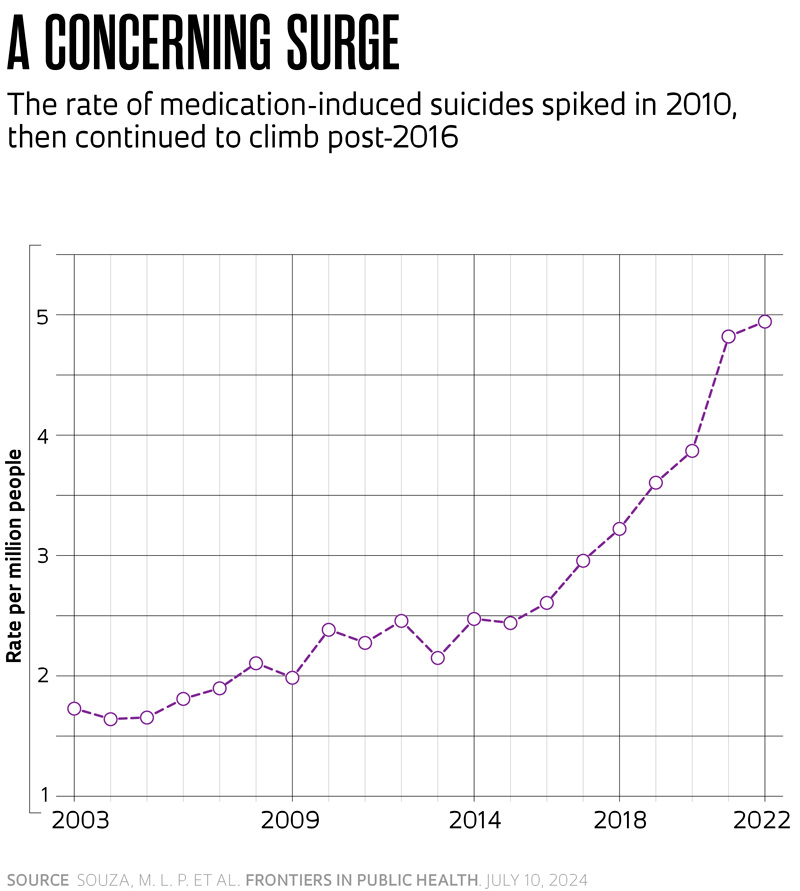

Suicide by ingestion of medication appears to be escalating in Brazil. According to a study published in July in Frontiers in Public Health, medication-induced suicides rose from 253 cases in 2003 to 922 in 2022, a 2.6-fold increase. Suicides by all methods doubled from 7,861 cases to 16,462 over the same period. Deaths by medication-related self-poisoning, which made up 3.2% of suicides at the start of the last decade, now account for 5.6%.

“This rise in medication-induced suicide deaths may suggest a shift in suicide methods in Brazil,” says Jesem Orellana, an epidemiologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) in Manaus and one of the study’s authors. “This is concerning from a public health perspective, particularly in terms of controlling access to medications. Here in Manaus, we often see people laying out canvases on the streets to sell medications, including prescription drugs,” he notes.

In the study, Orellana, along with colleagues from FIOCRUZ and the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel), used data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health’s Mortality Information System (SIM) to analyze suicide deaths involving medication in people aged 10 and older during the past two decades.

The researchers found a distinctive pattern among individuals who die by medication-induced suicide. Most cases involve women (55%), single individuals (52%), and people who self-identify as white (53.2%). Deaths are concentrated in the Southeast (41.7%), though a significant number also occur in the South (22.8%) and Northeast (21.6%). Two out of three deaths occur in healthcare facilities, which may be due to the fact that this method does not lead to immediate death.

Previous studies have shown that, in general, men are more likely to die by suicide. In the Americas, which have seen an increase in self-inflicted deaths—contrary to global trends—three men die by suicide for every woman who takes her own life. But a study led by Brazilian psychiatrist Renato Oliveira e Souza, head of the Mental Health, Substance Abuse, and Rehabilitation Unit at the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), points to a faster rise in female suicide rates. According to the research, published in 2023 in The Lancet Regional Health – Americas, suicide rates grew by 1.25% per year among women and 0.49% per year among men from 2000 to 2019.

A wide range of medications were found to be involved in drug-induced suicides. In 40% of cases, the drugs used affect the central nervous system—such as sedatives, medications for epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease, and other psychotropic drugs. In 55% of cases, the specific medication used was not reported.

“Women seek medical help more frequently than men do and are more likely to use medications available at home, such as psychotropics,” says psychiatrist Neury Botega, a retired professor at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), who years ago led the FAPESP-funded Brazilian leg of a study on the use of phone-based follow-up to reduce suicide rates (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 158). “Men, on the other hand, tend to use more violent methods, such as hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms,” explains the researcher. Botega, who authored the book Crise suicida: Avaliação e manejo (Suicidal crises: Assessment and management; Artmed, 2nd edition, 2022), notes that suicide cases have also risen significantly among teenagers and young adults in Brazil.

There are many reasons why, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 700,000 people take their own lives each year worldwide. In high-income countries, suicide is often linked to mental health issues, especially depression and alcohol abuse. But people also commit suicide impulsively during crises, after experiencing a major loss or ending a relationship, when feeling isolated, after becoming victims of abuse or violence, or due to financial distress.

According to the Frontiers in Public Health article, significant increases in deaths from medication self-poisoning in Brazil coincided with periods of regional and global crises—rates began rising in 2010 and peaked in 2022 (see chart).

“These are likely an indirect effect of the economic, political, and fiscal crisis that gripped the country from 2016 onwards, coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic,” suggests Orellana of FIOCRUZ. “In Brazil, there are indications that, following a period of strong economic growth that ended around 2010, people’s loss of jobs and social safety nets may have driven the ensuing increase in suicide rates,” says psychiatrist Pedro Magalhães from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). He led a 2019 study published in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology that examined changes in suicide rates in Brazil between 2000 and 2016.

“A specialized mental health network, like Brazil’s Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS), needs to be widely available to address mental suffering, which can be triggered by a variety of causes,” says public health expert Stela Meneghel from UFRGS, who researched the rise in suicide rates in Rio Grande do Sul during the 1980s and 1990s. “The previous federal administration chose to invest in religious-based therapeutic communities, which use a misguided approach to treating mental suffering,” she says.

According to Botega, faith can offer some protection against suicide by providing a structured belief system and promoting behaviors that are beneficial both physically and mentally. “However,” he cautions, “many religious and cultural beliefs can increase the stigma around suicide and may discourage people from seeking medical help.”

In 2003, Brazil designated September as Suicide Prevention Month. But Botega notes that significantly more needs to be done. “We still lack a national suicide prevention plan, unlike most developed countries that have dedicated budgets, regional research, and regionally tailored strategies,” he explains. “It’s crucial that prevention and awareness efforts are not left solely in the hands of coaches and influencers, who may inadvertently add to the distress of those dealing with loss.”

The media has a duty to be responsible in its reporting on this topic. “Observational studies have shown that the way a suicide case is reported can influence local suicide rates,” says Magalhães. A study published in July in Science Advances found that news coverage of suicides involving celebrities or public figures increased the spread of suicidal thought and behavior in the US.

If you have experienced or are currently experiencing suicidal thoughts, seek help from a mental health service or reach out to one of the hotlines provided by the Brazilian Center for Life Preservation (CVV), which can be reached at 188. CVV is a free, confidential, and volunteer-run suicide prevention service operated by a nonprofit organization.

The story above was published with the title “Medication-related suicide on the rise in Brazil” in issue 343 of September/2024.

Scientific articles

SOUZA, M. L. P. et al. The rise in mortality due to intentional self-poisoning by medicines in Brazil between 2003 and 2022: Relationship with regional and global crises. Frontiers in Public Health. July 10, 2024.

LANGE, S. et al. Contextual factors associated with country-level suicide mortality in the Americas, 2000–2019: A cross-sectional ecological study. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas. Feb. 23, 2023.

MARTINI, M. et al. Age and sex trends for suicide in Brazil between 2000 and 2016. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. Mar. 20, 2019.

SHAMAN, J. et al. Quantifying suicide contagion at population scale. Science Advances. July 31, 2024.