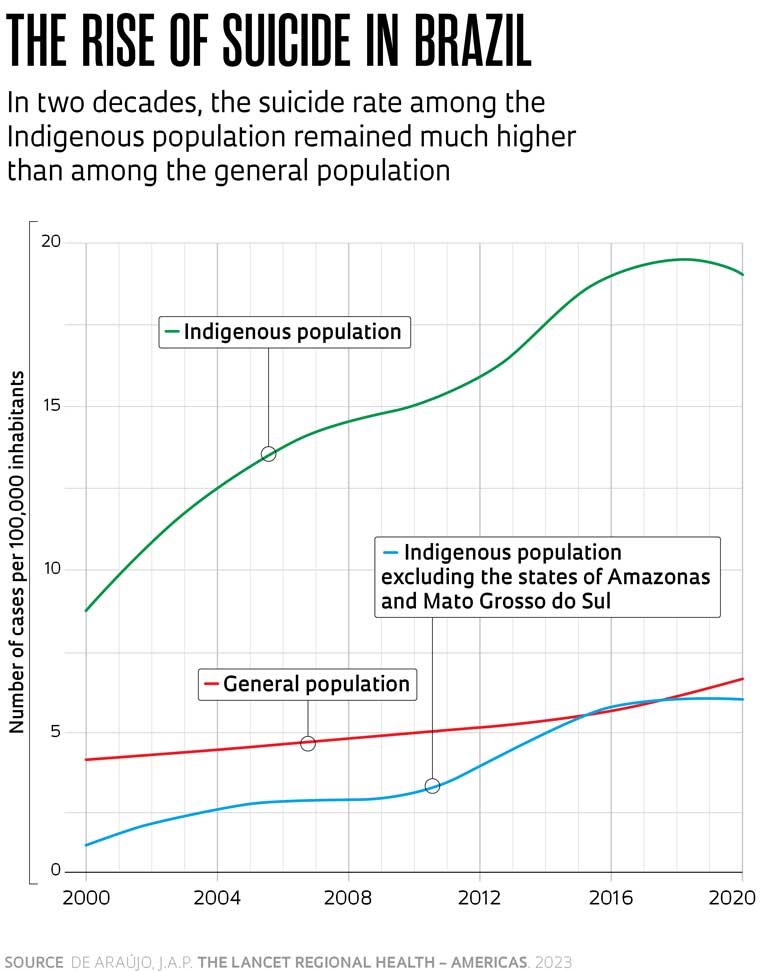

The already-high suicide rate among Indigenous people in Brazil has risen even further this century, remaining well above that of the general population. According to the most comprehensive survey on the subject, published in the journal The Lancet Regional Health – Americas in September, the suicide rate among native peoples was 9.3 for every 100,000 individuals in 2000, and it almost doubled to 17.6 per 100,000 people in 2020. In the same period, the average suicide rate among the Brazilian population as a whole also increased, but to much less of an extent. It rose from 4.6 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants to 6.4—an increase of approximately 39%. The outcome of this disparate increase is that the suicide rate among Indigenous people is now 2.7 times higher than in the general population.

The Lancet study, which was the result of a collaboration between researchers from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) and Harvard University, is the first to assess the problem among Indigenous Brazilians at a national level. Previous surveys had indicated that the suicide rate among the general population in Brazil, despite being considered low compared to other countries, was on the rise. There were, however, gaps in the data regarding Indigenous Brazilian peoples. Previous studies measured the problem in specific states and over shorter periods, wrote the authors of the new article.

In this study, psychiatrist Jacyra de Araújo and her colleagues determined the recent rise in suicide rates in Brazil based on figures recorded in the Brazilian Ministry of Health’s Mortality Information System. First, they identified the total number of individuals who took their own lives between 2000 and 2020, among both Indigenous people and the general population. They then divided that number by the total number of individuals in each group (Indigenous and general population) according to the 2010 Census, which provided the most recent data available at the time: 196.4 million people lived in Brazil, of which 897,000 were Indigenous. The absolute number of individuals was corrected for each year based on projections from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

The study made another disturbing conclusion. The act of taking one’s own life, indicative of a profound sense of helplessness and often associated with mental health problems such as depression, has proven to be a more prominent problem among young Indigenous people this century. Of the 2,021 cases of suicide recorded among Indigenous people in the period, 64% involved individuals aged under 24 and 68% were single — almost always (90%) caused by hanging, suffocation, or strangulation. In the general population, the risk of suicide is highest in those aged over 60.

Another important point is that the suicide rates observed in these populations, while alarmingly high, may even be underestimates. “The quality of the Mortality Information System has improved over the last 20 years, but there are indications that suicides are still underreported, which is common worldwide due to stigma and the difficult nature of establishing whether the intention was to die,” explains Araújo, who is an associate researcher at FIOCRUZ’s Data and Knowledge Integration Center for Health (CIDACS) in Bahia and lead author of the article. “The real rates may be even higher than those calculated in this study,” he states.

A peculiar pattern caught the attention of the researchers. Suicide rates varied greatly between Brazilian regions, even between those with large Indigenous populations. For example, the rates were several times higher in the Central-West and North of the country — which have the third and first highest number of descendants of Indigenous peoples respectively — than in the Northeast, which has the second largest Indigenous population in Brazil. “Indigenous suicide occurs in all regions and among all ethnicities, but it is disproportionately higher in certain states,” explains epidemiologist Jesem Orellana of FIOCRUZ’s Leônidas and Maria Deane Institute in Amazonas, coauthor of the article, which also included the participation of scientists from Harvard Medical School and received funding from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Going against the trend, the suicide rate among Indigenous people in the central-western states dropped from 46 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in 2000 to 34 per 100,000 in 2020. According to the 2010 Census, 143,400 descendants of Indigenous peoples lived in the region (16% of the country’s Indigenous population). Despite the significant drop, however, the rate remains much higher than the national average. In the North region, inhabited by 342,900 Indigenous people (38.2% of the total), the suicide rate increased more than tenfold in the period, jumping from 2.7 cases per 100,000 people to 29. The Northeast, home to 232,700 Indigenous people, also saw an increase, but it was a much smaller one. The rate went from 1.4 deaths per 100,000 individuals to 4.8, which is well below the national average.

The states with the highest suicide rates are Mato Grosso do Sul and Amazonas. In the former, where 77,000 Indigenous people live, the rate reached a frightening peak of 105 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2005, and it never fell below 43 per 100,000 in the period studied. With 184,000 descendants of Indigenous peoples, the rate in Amazonas rose from 0.99 in 2000 to a peak of 45 in 2014—in 2020 it was 38.6 per 100,000. “When data from these two states are excluded, the suicide rate among Indigenous people is almost identical to that of the general Brazilian population,” says Orellana.

The situation in Brazil, as described in the Lancet article, is similar to that observed in other countries. In a review published in the journal BMC Medicine in 2018, Canadian researchers compiled data from 99 scientific articles on Indigenous suicide in more than 30 nations and territories. They concluded that suicide rates are often higher among Indigenous peoples than non-Indigenous populations, especially in countries such as Brazil, Canada, and Australia.

Danilo Verpa / Folhapress

A man from the Karajá ethnic group stands beside the graves of three children who took their own lives

Danilo Verpa / Folhapress Although the FIOCRUZ study did not delve into the reasons why Indigenous people are more likely to commit suicide, other studies have provided some clues. In a review article published in Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública in 2020, a group led by Maycoln Teodoro, a psychologist from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), listed the most frequent causes as poverty, low indicators of well-being, historical and cultural factors, family disintegration, and a lack of meaning in life.

Invasions of their land and expulsion from territories where they originally lived, in addition to environmental degradation and forced changes in lifestyle habits, are among the factors that lead to so-called “cultural death,” another potential trigger of suicidal behavior. Some of the experts interviewed for this report also gave other reasons that may contribute to the higher suicide rates among Indigenous people than the rest of the population. They have less access to the educational system and health services. They also face higher levels of unemployment, while alcohol consumption and dependence is on the rise. Previous studies have identified that the loss of Indigenous identity and the sexual violence more commonly experienced by young people contribute significantly to the problem.

According to Juliana Kabad, a social scientist from the Institute of Public Health at the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), the causes that lead to suicide may vary between ethnic groups. “There are countless factors behind this problem. To identify them, we need to listen to the different Brazilian Indigenous peoples and take into account the struggles each of them face in the form of persistent discrimination and plundering of their lands,” says the researcher, who was not involved in the Lancet study.

“Urgent action is needed to understand the suffering these young people experience due to violence and the severing of ties with their own community, so that we can fully support them,” says anthropologist Sandra Garcia of the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP), who was not involved in the Lancet study. “Combining nationwide and group-specific strategies, and considering ethnic diversity, is extremely important to suicide prevention,” she stresses.

Orellana, from FIOCRUZ in Amazonas, notes that from an epidemiological standpoint, some ethnicities are in more vulnerable situations than others. The Guarani-Kaiowá from Mato Grosso do Sul, for example, have experienced clusters of suicides in the past, especially among the youngest age groups, as documented in a 1991 article in Cadernos de Saúde Pública. “Identifying these ethnicities is important to defining adequate prevention strategies, one of the priorities of the current administration,” says Matheus Cruz, a psychosocial care and healthy living technician from the Ministry of Health’s Department of Indigenous Health (SESAI).

Scientific articles

DE ARAÚJO, J. A. P. et al. Suicide among Indigenous peoples in Brazil from 2000 to 2020: A descriptive study. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas. Sept. 14, 2023.

BONFIM DE SOUZA, R. S. et al. Suicídio e povos indígenas brasileiros: Revisão sistemática. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. June 29, 2020.

POLLOCK, N. J. et al. Global incidence of suicide among Indigenous peoples: A systematic review. BMC Medicine. Aug. 20, 2018.

MORGADO, A. F. Epidemia de suicídio entre os Guarani-Kaiowá: Indagando suas causas e avançando a hipótese do recuo impossível. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. Dec. 1991.

Republish