MÁRCIO BORGES MARTINS Pampa, a word of Quechuan origin meaning a flat region: only recognized as a Brazilian biome in 2004MÁRCIO BORGES MARTINS

The use of both fire and livestock have played an important and often essential role in maintaining the biological diversity of the Pampa Biome, one of the richest, most complex and heterogeneous Brazilian ecosystems. It may sound strange, but studies suggest that these two forms of human intervention, which are almost always hostile to local biodiversity, can, if well managed, contribute to conserving the grassland vegetation of southern Brazil by containing the invasion of Araucaria forests and the density of woody plants in the region and promote the regrowth of native vegetation, often used for cattle feed. This unusual idea of environmental conservation was the highlight of lectures by Márcio Borges Martins and Ilsi Iob Boldrini, both biologists at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), at the second meeting of the BIOTA-FAPESP Education Conference Cycle held in São Paulo on March 21. The event represented a partnership between the BIOTA-FAPESP Program and Pesquisa FAPESP, and also included Eduardo Eizirik, a biologist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS).

According to the researchers, in the last thousand years, the humid climate, characteristic of subtropical zones, has favored the expansion of forests at the expense of grasslands, which until recently made up the landscape of the southern region. “Considering the current climate, almost the entire southern region of Rio Grande do Sul should be covered by forest vegetation,” Martins pointed out. According to him, the only thing that kept this from occurring was the presence of large herbivores living there and, more recently, the introduction of livestock. “Cattle have played a vital role in conserving the pampas,” he said. There is also fire, which stops the rapid advance of forests. “Fires may have been essential in maintaining the natural dynamics of grassland vegetation,” Martins asserted. Some scholars believe that its use is related to the arrival of indigenous peoples in the region, who used it along with a more seasonal climate for hunting and land management.

For Martins, in addition to fire and grazing, other factors that influence the composition and physiognomic characteristics of grassland vegetation include soil type, drought conditions, frost, trampling of fields by animals and periodic mowing. He then went on to say that such disturbances must be taken into account when proposing sustainable forms for managing the grasslands in the region, as these are factors that hinder the expansion of forests into grassland areas. Martins noted, however, that poor management of these disturbances can lead to degradation of this ecosystem.

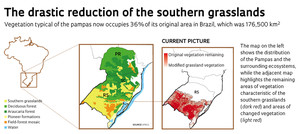

Currently the Pampa Biome is the second most devastated in Brazil — the most degraded is the Atlantic Forest. Its grasslands are scattered over 176,500 square kilometers, which represent 63% of the land area of Rio Grande do Sul and 2.1% of the land area of Brazil. Today only 36% of the original vegetation of the pampas has been preserved, said Ilsi Iob Boldrini.

According to Boldrini, because it is contained within the southern portion of Rio Grande do Sul, the biome has received little public attention with regard to implementing environmental conservation policies. In part, this is because the region was only officially recognized on the map of Brazilian biomes in 2004, and its biological diversity before then was underestimated.

“Although it covers a relatively small area, the Pampa Biome is very heterogeneous. Not only does it offer physiognomic diversity and varied habitats that include flat fields, along with rocky and sandy areas, but it also has low areas with waterlogged soils that flood during much of the year and forest environments. It is a complex biome with diverse types of vegetation, among which fields dominated by grasses are the most representative,” Boldrini said.

LÉO RAMOS From left to right: Eduardo Eizirik, Ilsi Iob Boldrini

and Márcio Borges MartinsLÉO RAMOS

To her, the number of new species identified in the region in recent years is also impressive. More than 2,000 plant species have been catalogued, and 990 of them are endemic to the pampas. “It is often thought that grassland vegetation is homogeneous and that all fields are the same. However, the diversity of species found in these areas is up to three times higher than in forest areas,” she said. The richest plant families in the pampas are the Asteraceae, with 380 species, Poaceae, with 373, Leguminosae, with 190, and Cyperaceae, with 118.

Many, however, are endangered as a result of replacing original vegetation with summer and winter crops (mainly soybeans, wheat and rice), of the use of forestry practices, and overgrazing by livestock, in which excessive exposure to cattle prevents the grasslands from recovering. “The activity of the region is cattle ranching, not agriculture. But when the herds are mismanaged, the vegetation is degraded,” she said.

The establishment of various agricultural systems, which are not always sustainable, has also altered the original vegetation at an accelerated pace. On many properties, the number of livestock is sometimes much greater than the capacity of the grassland vegetation to support them. And in the absence of native pastures, many producers resort to planting exotic grasses and legumes, in addition to applying herbicides, which contaminate soil and groundwater. In addition to overexploitation of the grasslands, replacement of the original vegetation with crops for grain or pulp production is distorting the landscape of the biome.

The use of herbicides on the original vegetation of the pampas in order to introduce forage species, inadequate management of natural grasslands and indiscriminate use of fire have also contributed to the destruction of this biome. And, despite recent advances, the grasslands of southern Brazil remain largely unknown. “Floristic and phytosociological surveys are still needed in order to obtain more precise estimates of the richness of species in the region,” Boldrini said in conclusion.

Changing landscape

Eduardo Eizirik and Márcio Borges Martins also pointed out that little is known about the vertebrate fauna of the Pampa Biome. Currently, concern for conservation of the diverse fauna of the region has increased because of the strong expansion of monoculture and eucalyptus cultivation for pulp (forestry). “Over the last decade the government has strongly encouraged forestry practices in the poorest regions of the state with a view toward economic development,” said Martins.

According to him, many companies have already purchased large tracts of land to grow eucalyptus for pulp production even before completion of a zoning study to identify areas suitable for planting. “Replacing the landscape with a dense eucalyptus forest could lead to a number of complications in maintaining the biodiversity of the grasslands,” he said.

MÁRCIO BORGES MARTINSIntroduced by the Jesuits in the 16th century, cattle may have contained the advance of forests on the pampasMÁRCIO BORGES MARTINS

One such complication is the blocking of gene flow between species. According to Eizirik, conservation policies for local biodiversity should aim at maintaining natural evolutionary processes. “Populations of the same species distributed in different geographical areas can become genetically differentiated,” he said. According to Eizirik, this can happen because of several factors, including separation by distance, natural selection itself and the emergence of barriers to gene flow. These barriers can range from desert regions to rivers and dense forests, such as eucalyptus. “Ignoring these problems can lead to the disappearance of some species that are important to maintaining local biodiversity,” Eizirik said. He worries about this problem, because the pampas extend into other Latin American countries such as Argentina and Uruguay. “So it is critical for phylogenetic and phylogeographic studies to be conducted as a basis for formulating conservation policies on vertebrate fauna in the southern grasslands,” he said.

Similarly, current networks of protected areas are far from ideal. Today the region has 11 conservation units with full protection, including parks and environmental reserves, which cover an area of 1,130 km2.“This represents only 0.64% of the area of the pampas,” Martins said. The 2010 National Biodiversity Targets established by the National Biodiversity Commission (Conabio) in 2006 included the goal of protecting 10% of terrestrial biomes in conservation units, with the exception of the Amazonia Biome which targets 30%. According to Martins, one of the reasons for the neglect of the pampas in preservation policies is that the visual impact caused by grassland degradation is small. “When you lose part of a forest, there is a significant change in the landscape. This is not true when it comes to the grasslands,” he said.

Learning for better use

The three biologists believe that despite human intervention, which has historically been part of maintaining the biodiversity of the southern grasslands, they are still a long way from achieving a level of understanding that enables sustainable management. At the same time, they do not want to compromise the natural biodiversity dynamics of the biome and the productivity of the economic region. They also stressed the critical need to revise the management models for these conservation units, which are currently preventing management through the use of fire and cattle. “There are a number of studies on sustainable ways to manage local biodiversity that preserve the characteristics of the pampas along with livestock development,” said Martins. “It is important to consider the region’s potential for other purposes such as the production of wind energy,” he added.

The BIOTA-FAPESP Education Conference Cycle will extend through the month of November and will address ideas, challenges and principal threats related to the six Brazilian biomes: Pampa, Pantanal, Cerrado, Caatinga, Atlantic Forest, and Amazonia, in addition to marine and coastal environments and biodiversity in urban and rural anthropic environments. The goal is to present the state-of-the-art of scientific knowledge acquired by BIOTA-FAPESP during its 13 years, in language that is accessible to diverse audiences, in order to improve the quality of science and environmental education for teachers and high school students in Brazil.

Republish