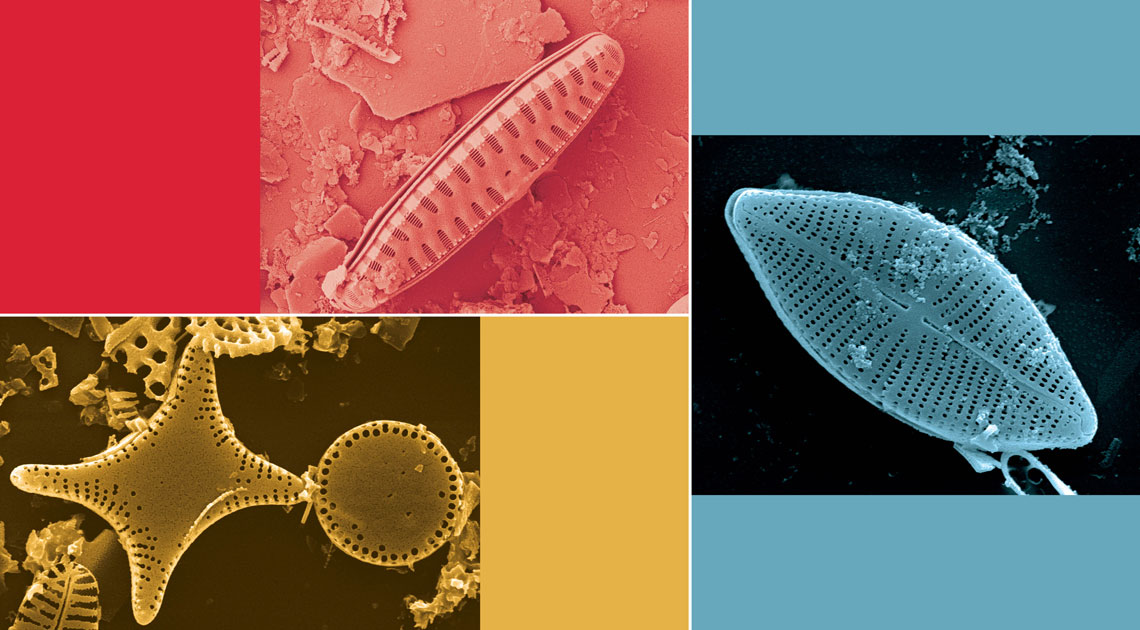

Single-celled microalgae, just 20 to 50 micrometers long, have helped scientists peer more than 500,000 years into the past to uncover what the climate of the Atlantic Rainforest was like during the Middle Pleistocene. Diatoms—organisms found in aquatic environments—have rigid silica-based cell walls (similar to glass), which allow their structures to remain well-preserved in sediment layers over thousands of years. Each species of diatom thrives in highly specific environmental conditions, such as water type, depth, acidity, and nutrient levels. Because of this, their presence serves as a precise indicator of an ecosystem’s characteristics at a given point in time.

Drawing on these microscopic clues, biologist Gisele Marquardt, from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), investigated the environmental transformations of the Colônia basin in southern São Paulo over hundreds of thousands of years. This area, home to a circular geological formation about 3.6 kilometers (km) in diameter—also known as the Colônia Crater—is considered one of the world’s most important tropical paleoclimate sites.

Sediment analysis revealed a recurring pattern across climatic cycles. During glacial periods, characterized by lower global temperatures and the expansion of polar ice caps (though not into South America), humid conditions and rising water levels prevailed, leading to widespread flooding. In contrast, interglacial periods brought warmer, drier conditions and reduced water coverage. “We were able to trace how the lake in the Colônia basin gradually transformed into a peat bog, a process that began at the edges and only later reached the center,” says Marquardt, author of a study published in December in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.

Beyond climate variations, local factors such as geology, sediment composition, and vegetation also played a role in the lake’s transition to a peat bog—a waterlogged ecosystem where the lack of oxygen slows the decomposition of organic matter. These findings suggest that tropical ecosystems can respond to climate change in diverse and complex ways. “Our data shows that this transformation process is older than previously thought—going back 500,000 years—and more intricate than a simple response to global climate patterns,” explains Marquardt. The research could offer insights into future changes in wetland environments and underscores the importance of their conservation.

“The diatom record was essential for understanding how a lake changes over time. And that’s highly relevant today—many lakes are evaporating or undergoing similar transformations due to climate change and heavy water use for irrigation,” says French paleoecologist Marie-Pierre Ledru, a researcher at the Research Institute for Development (IRD) in France and one of the coauthors of the study.

To collect diatom samples, the research team used a manual hammering system mounted on a tripod to insert a core tube to a depth of 14.7 meters (m). The deepest layers represent the oldest material, while the uppermost layers are the most recent. From this sediment core, samples were taken at intervals of 3 to 4 centimeters between depths of 14.7 and 8 meters. Each segment yielded a small volume of soil—just 0.5 cm³—resulting in 160 subsamples for the analysis of fossilized microalgae.

The samples underwent a chemical treatment to remove organic matter and carbonates, leaving behind the diatoms’ frustules—their silica shells, made up of two interlocking valves—which could then be examined under a microscope. For each slide, researchers counted a minimum of 400 valves, identifying the species and classifying them as either planktonic (suspended in the water column) or benthic (attached to submerged surfaces like rocks, plants, or sediment).

The presence of planktonic diatoms suggests an active, open lake environment with high water levels, typically associated with humid glacial periods. In contrast, the prevalence of benthic species points to shallower conditions or a transition to a peat bog, indicating drier phases or dense vegetation covering the water’s surface.

“We were able to identify the species collected and discovered that many of them in Colônia have never been described before. It’s an extremely diverse environment,” says Marquardt.

Eduardo Cesar / Pesquisa FAPESPThe crater, located in Parelheiros, is around 4 km in diameterEduardo Cesar / Pesquisa FAPESP

The research was conducted during her postdoctoral work at what was then the Botanical Institute of São Paulo, which became part of the Environmental Research Institute (IPA) in 2021. Funded by FAPESP, the project aimed to track changes in diatom communities and use them as biological indicators for paleoenvironmental reconstruction in the Colônia basin.

Although the study focused on the São Paulo site, the findings—published in December—were compared with sediment records from Lake Titicaca in the Andes. Despite differences in altitude and geography, both environments showed similar climatic responses to global oscillations: colder periods were marked by greater humidity and expanded water bodies, while warmer intervals brought reduced moisture and lower water levels.

However, differences in the types of diatoms found suggest that global climate alone does not explain all environmental changes. In Lake Titicaca, benthic species dominated during glacial periods, pointing to shallow conditions. In contrast, the Colônia basin showed a predominance of planktonic species in the same periods—indicating deeper, more dynamic waters. This led researchers to hypothesize that local factors such as topography, vegetation, and water depth may have played an equal or even greater role than global climate shifts in shaping ecological dynamics.

“Our current climate models are based on about 40 years of data. A record like the one presented in this study—with such deep historical insight, even revealing variations within a single sub-basin—is extremely valuable,” says Brazilian biologist Luciane Fontana, now at Lanzhou University in China.

A specialist in paleoenvironmental reconstruction, Fontana uses diatoms and other biological markers in her own research, although she was not involved in Marquardt’s study. She emphasizes the importance of this type of data: “The predictive models we use today can and should incorporate this kind of information to become more robust, as diatoms are excellent bioindicators—they respond quickly to environmental changes.”

Another study, published in March in the journal Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, highlights the rich diversity of fossil pollen and spores preserved in the sediments of the Colônia basin, also dating from the Middle Pleistocene (between 530,000 and 370,000 years ago). Authored by Paraguayan paleoecologist Olga Aquino-Alfonso and Marie-Pierre Ledru, the article identifies 146 types of palynomorphs (microscopic organic particles) that document the ancient vegetation of the Atlantic Forest prior to the onset of the planet’s 100,000-year glacial cycle.

Combining microscopy techniques and ecological analysis, the study reveals a humid and diverse forest, with species that are now rare, such as araucarias and podocarps, and the absence of others like Acaena and Ephedra, suggesting major environmental shifts over time. “We found a mix of Cerrado species alongside plants now considered cold-adapted, from the Pampa region,” says Ledru.

She explains that during the ice ages, sea levels were about 100 meters lower, pushing the coastline farther away and reducing the humidity needed to sustain the Atlantic Forest. “The coast was farther out. As humidity decreased, drier species began to take hold and expand—until the moisture returned and the sea level rose again,” she explains. These records, she adds, underscore the need for careful monitoring of today’s biomes, as their boundaries may shift more rapidly than expected under current climate change scenarios.

Projects

1. Changes in diatom assemblages in response to climate and environmental changes during glacial and interglacial cycles in an Atlantic Forest region located in an urban area (n° 18/23399-0); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Carlos Eduardo de Mattos Bicudo (Instituto de Botânica); Beneficiary Gisele Carolina Marquardt; Investment R$177,857.36.

2. Challenges for biodiversity conservation in the face of climate change, pollution, and land use and occupation (PDIp) (n° 17/50341-0); Grant Mechanism Research Grant – State Research Institutes Modernization Program; Principal Investigator Luiz Mauro Barbosa (Instituto de Pesquisas Ambientais); Investment R$9,612,432.65.

3. Dimensions US-Biota São Paulo: Integrating disciplines for predicting Atlantic Forest biodiversity in Brazil (n° 13/50297-0); Grant Mechanism Biota Program; National Science Foundation (NSF) Agreement; Principal Investigator Cristina Yumi Miyaki (USP); Investment R$4,517,876.44.

4. Paleolimnological reconstruction of the Guarapiranga dam and diagnosis of the current water and sediment quality in springs in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area with regard to water supply management (n° 09/53898-9); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator: Carlos Eduardo de Mattos Bicudo (Instituto de Botânica); Investment R$1,725,042.01.

Scientific article

MARQUARDT, G. C. et al. From paleolake to peatland: Paleo environmental changes over glacial and interglacial cycles (Mid-Pleistocene) in the Colônia Basin, Brazil. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Vol. 655. Dec. 2024.