“After that work for [the magazine] Realidade [published in 1971], I went back to Amazonia every year until 1975, and then again in 1978. There was a plan to release a book on those travels at the end of that year. In fact, it arose from convictions about the nature of photography and the experience in the region, in an attempt to reconcile ideas from both these worlds. Amazonia was the theme, but the aim was to demonstrate that a photo is not a faithful representation of the subject. The book was arranged to explain that thesis—that what the photograph shows is an impression of reality, just my impression. […] The book was never understood. Also, it was simply banned during the heyday of censorship.”

The above testimony was given by American photographer George Love (1937–1995) to São Paulo State native photographer and curator Zé De Boni for the biography Verde lente: Fotógrafos brasileiros e a natureza (Green lens: Brazilian photographers and nature) (Empresa das Artes, 1994). Love, who lived in Brazil between the 1960s and 1980s, was alluding to Amazônia (Praxis, 1978), a work in conjunction with photographer Claudia Andujar, which was censored by the military dictatorship regime (1964–1985), as historian Vitor Marcelino da Silva explains in his doctoral thesis “A construção coletiva de Amazônia: Fotografia e política no livro de Claudia Andujar e George Love (The collective construction of Amazônia: Photography and politics in the book by Claudia Andujar and George Love),” defended in 2022 under the Program for Inter-unit Postgraduation in Art Aesthetics and History at the University of São Paulo (USP).

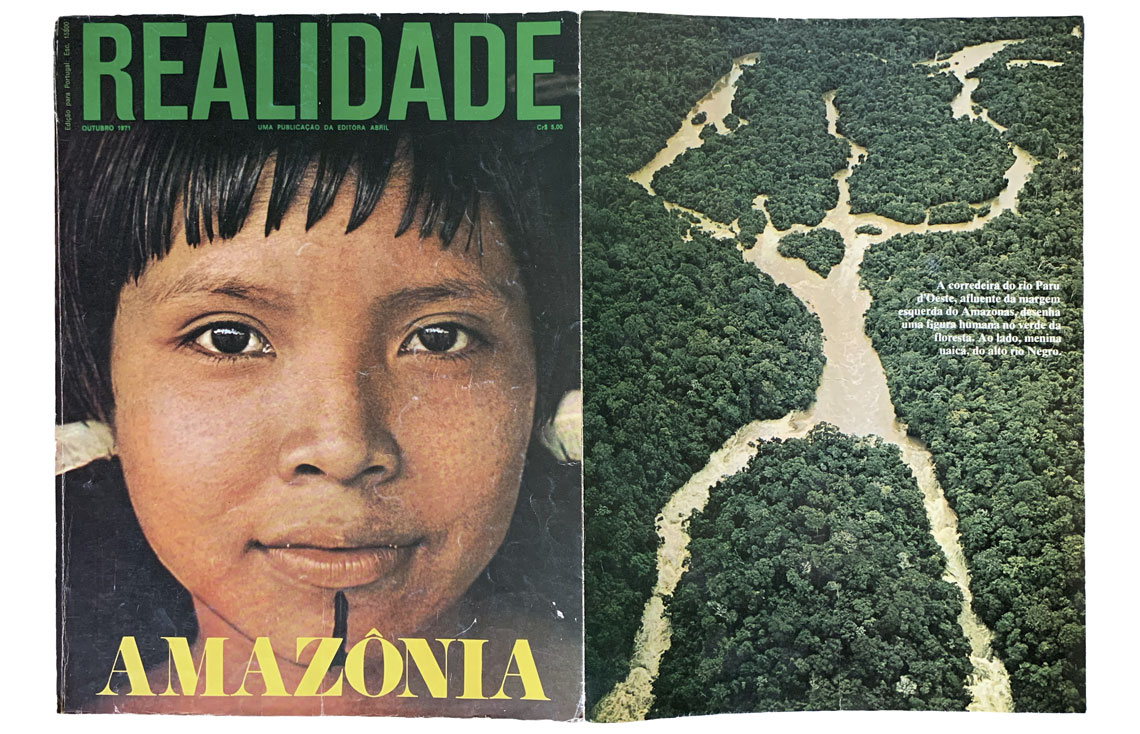

Reproduction Vitor Marcelino da SilvaFront and rear covers of the special in Realidade magazine; portrait by Claudia Andujar and aerial image by LoveReproduction Vitor Marcelino da Silva

“The poetry of Thiago de Mello [1926–2022], with its condemnatory tone on destruction of the forest, and Love’s images of burning, bothered the military,” says Silva, whose research into the book won first prize in the category Letras, Linguística e Artes (Letters, Linguistics, and Arts) in the 12th Edition of the USP Standout Thesis Award, conceded at the end of last year. “The theme of forest devastation was cut by the censors.”

In the first part of its 162 pages, Amazônia shows aerial images captured by Love — one of his trademarks — in the states of Amazonas and Pará, and the then territories of Roraima and Amapá. The second block carries a sequence of photos of the Indigenous Yanomami ethnicity, taken by Andujar. According to Silva, the book was put together collectively and should not be seen as an “original one-author product in the traditional sense,” as it involves different agents. As well as the names of Love and Andujar, the historian highlights the work of editor Regastein Rocha (1935–2021), owner of Praxis and the executive head of the project.

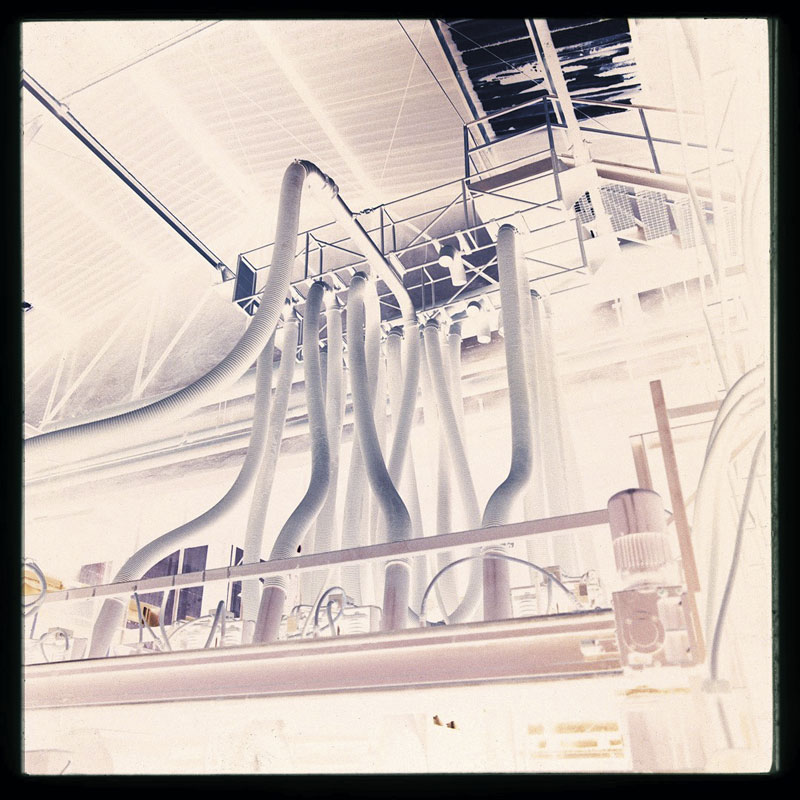

George Love, corporate profile, 1970s; Courtesy of George Love: Beyond Time / MAM-SPIndustry catalog photo in the 1970sGeorge Love, corporate profile, 1970s; Courtesy of George Love: Beyond Time / MAM-SP

The publishing and graphics house, set up in 1977 and closed one year later, provided services of publicity, print production, and gifts for Sharp Brasil. Opening five years previously, the electro-electronics and computer company was headquartered in São Paulo and had factories in the Manaus Free-Trade Zone. Its owner, southern Brazilian Matias Machline (1933–1994), had links with the military regime, as the thesis indicates, and was close to Generals Ernesto Geisel (1907–1996) and João Baptista Figueiredo (1918–1999), the last two presidents of the dictatorship. “Among other businesses, Machline Group owner Zé Maurício Machline (which ran Sharp’s operation in Brazil) was a minority partner of Praxis,” adds Silva. “He and Regastein had known each other since the 1960s.”

In 1978, Praxis released four photography books: Xingu, by Maureen Bisilliat, Fotografias (Photographs), by Otto Stupakoff (1935–2009), Yanomami: Frente ao eterno (The Yanomami Struggle), by Andujar, and the aforementioned Amazônia. “Regastein’s interest in Amazonia gained momentum when he began traveling frequently to the Manaus Free-Trade Zone in the 1970s, in the service of Sharp Brasil,” explains Silva. According to the researcher, the company enfolded military personnel within its staff who were suspicious of the editor. “Regastein kept in contact with prominent figures from the resistance to the dictatorship, such as anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro [1922–1997]. Moreover, he started to invite former political prisoners and exiles to work on the firm’s publicity campaigns and publications,” the historian continues.

As the research indicates, one of these military figures embarked upon an internship at Praxis on the pretext of learning printing techniques to be used by the Army. “Regastein would later discover that the intern was spying on the production of three books, one of which on Brazilian Indigenous groups, arranged by Darcy Ribeiro; another on the presence of the Catholic Church in Brazil, organized by Cardinal Agnelo Rossi [1913–1995], criticizing the dictatorship; and, finally, Amazônia,” says Silva.

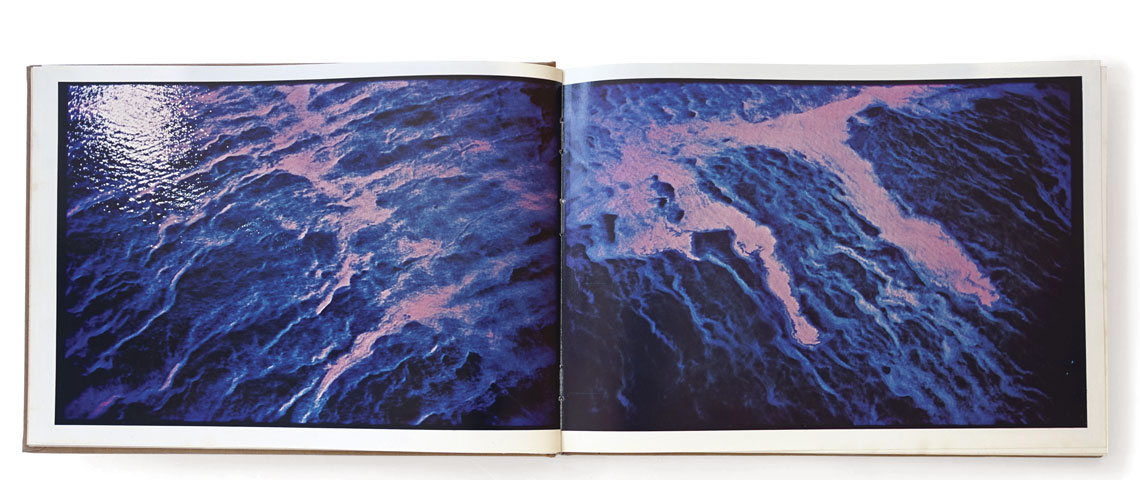

Leary-Love family archive, J. Murrey Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; reproduction Douglas CanjaniImage from AmazôniaLeary-Love family archive, J. Murrey Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; reproduction Douglas Canjani

In 1978, military personnel raided Praxis and seized all their machinery and materials. The first two books, still in the early stages of production, were never released. Amazônia was published in the end, but without Love’s photos of the forest burning, and also missing the essay by Thiago de Mello, exiled by the regime in 1968. The editor was interrogated, but discreetly distributed some 3,000 copies; the book was sold at two bookshops in São Paulo and another in Rio de Janeiro; some copies also made it overseas. “The initial idea was ambitious. Regastein was planning an international book launch, but that project never came to fruition,” says the historian, who interviewed the editor and Frances Rocha, a retired professor of the History Department at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC‑SP), during his research.

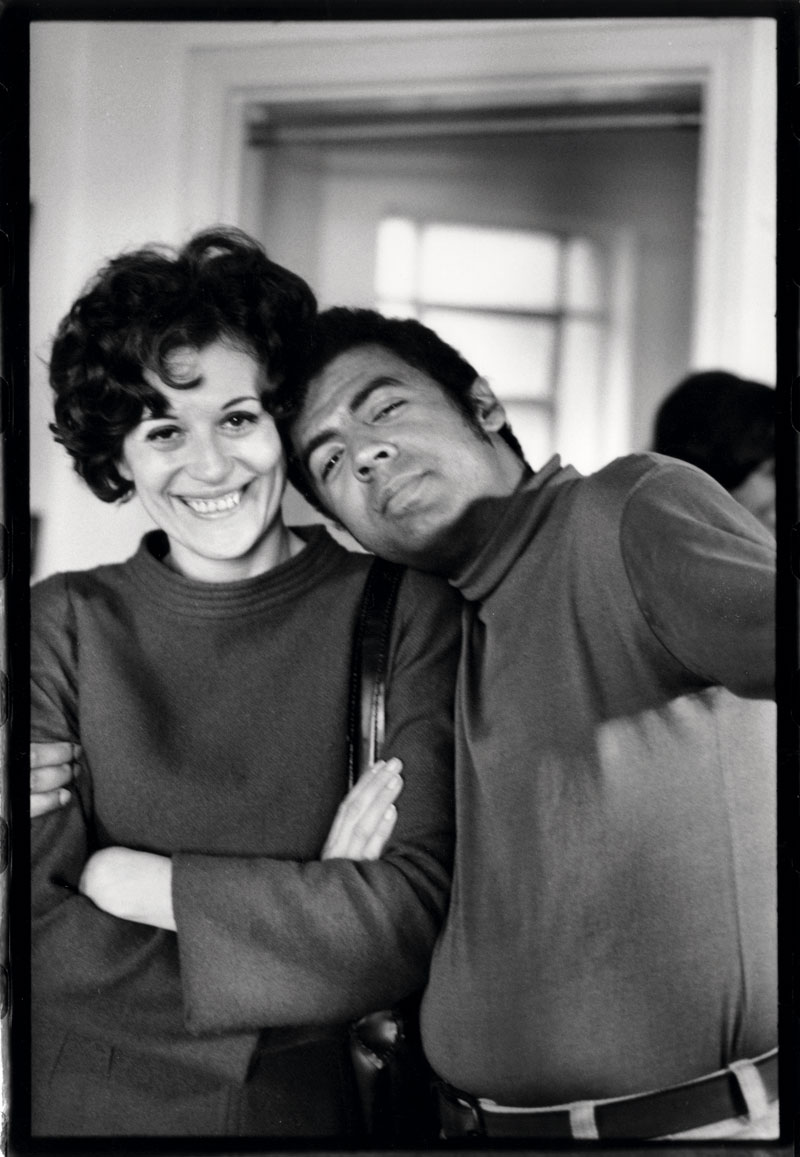

As well as the censorship, the thesis takes you on a journey through Love’s photography. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, USA, Love graduated in arts at the end of the 1950s at Morehouse College, an institution in Atlanta, Georgia, for Black students, with personalities such as activist Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) and filmmaker Spike Lee having studied there. Love moved to New York at the beginning of the 1960s and joined the Association of Heliographers, founded in 1963 by photographer Walter Chappell (1925–2000), to discuss photographic experimentation. There, Love organized exhibitions and assumed the role of vice director of the gallery inaugurated by the group. “George arrived in Brazil in 1966 to meet with Claudia Andujar, a Hungarian-Swiss photographer living in São Paulo since 1955,” says Douglas Canjani, a professor at the PUC-SP Department of Communication and author of a research piece on the photographer from his postdoctoral internship at the institution, concluded in 2020. “Claudia frequently traveled to New York and became involved in the Association of Heliographers; that’s how they met.”

Leary-Love family archive, J. Murrey Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; reproduction Douglas CanjaniImage from AmazôniaLeary-Love family archive, J. Murrey Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte; reproduction Douglas Canjani

The two lived as a couple until 1974. At the end of the 1960s, the pair began to collaborate with the magazine Realidade (1966–1976), of editorial house Abril, a publication that made Brazilian journalism history, primarily during its early years, with bold reporting that caused a considerable stir. “The magazine gave creative license to photographers, who contributed significantly to Brazilian photojournalism, producing images that blended documentary with experimentalism. This resulted in a highly innovative visuality in the press of that period,” observes Helouise Costa, faculty member and curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC‑USP), who advised on Silva’s thesis.

Reproduction Douglas CanjaniUrban landscape from São Paulo: Notes (1982), with photos taken by Love between the 1960s and 1980sReproduction Douglas Canjani

“Realidade broke away from a more descriptive use of photography, common among communication vehicles at that time,” agrees Marcelo Eduardo Leite, of the Interdisciplinary Institute of Society, Culture, and Arts at the Federal University of Cariri (UFCA), in Ceará State. In Love’s specific case, the ground was laid for him to put his previous experiences in the field of visual arts into practice at the forefront of the New York scene, such as “the use of colors, shutter-speed resources, framing, and contrasts,” adds Leite, author of the article “O fotojornalismo experimental de George Love na revista Realidade” (“The experimental photojournalism of George Love in the magazine Realidade”) (2023).

Love and Andujar were part of a team of 40 that produced a special on Amazonia for Realidade. Images in the edition, published in October 1971, include aerial photos taken by Love, and registration of Andujar’s first contact with the Yanomami Indigenous people. “The project inspired George to return to the region several times over the following years, later resulting in the publication of Amazônia in 1978,” says Canjani, who in 2014, with support from FAPESP, visited the photographer’s archive in the J. Murrey Atkins Library at the University of North Carolina. Among other aspects, the researcher analyzed Love’s relationship with landscape. “When taking photographs, George seems to be less interested in portraying the landscape in the form of a topographic prism carrying an exact description of the territory and its features, and more curious about the phenomena of light and the reciprocal action of landscape elements on each other (light, water, vapor, sky, earth, vegetation, etc.),” Canjani writes.

In Brazil, Love collaborated as a photojournalist on other publications, such as Novidades Fotoptica (Photooptic news) (1953–1987), a leading vehicle on photography in the country, and Bondinho (Cable car) (1970–1972), a supermarket chain magazine whose editorial staff had contributed to Realidade. “In the 1970s, he also participated in several initiatives at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), mostly in partnership with Claudia Andujar, such as creation of a photography department and implementation of a photographic laboratory, as well as exhibitions and courses,” says Costa, of MAC‑USP. In the early 1980s, Love was engaged by Eletropaulo to organize a collection of photographic documentation of São Paulo City. The project, led by architect Benedito Lima de Toledo (1934–2019) of the USP School of Architecture and Urbanism, gave rise to the publication of two books by editorial house Raízes, a new Regastein Rocha enterprise, in 1982. One of these is São Paulo: Registros (São Paulo: Records), with vintage photos from the company’s collection taken at the turn of the 19th–20th century. The other book, São Paulo: Anotações (São Paulo: Notes) showcases images captured by Love between 1966 and 1982.

Galeria Vermelho / Courtesy Claudia AndujarLove, in an undated photo with Claudia Andujar, his companion of eight years and professional partnerGaleria Vermelho / Courtesy Claudia Andujar

In 1988, the photographer set up in New York State, and at 50 years of age was going through a phase of “discovery and instability,” while also dealing with the health condition scoliosis (curvature of the spine), as Canjani reports. “The decision to return to the US had a negative impact on George’s professional career. He began isolating himself from the São Paulo cultural scene, where he had been widely accepted, and no longer having a broad social circle in the US after so many years living in Brazil, went through a period of solitude and ostracism,” continues the researcher. In 1995, Love visited Brazil, and passed away during an orthopaedic surgery in São Paulo at 58 years of age.

Love was not around for the rediscovery of Amazônia in the 2010s, with photobooks now valued in Brazil and around the world. One of the drivers of this work’s publication was its inclusion in Fotolivros latino-americanos (The Latin American Photobook) (2011), coordinated by Spanish curator Horácio Fernández, with versions in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese — the Brazilian version was released by publishing house Cosac Naify. Divided over nine themed chapters, this work presents 150 photobooks through images and small texts. Amazônia is part of the block Os esquecidos (The forgotten). “I think that one of the reasons for the success of the book was the fact that Claudia Andujar was consolidating at that time as a leading contemporary artist, but it has many qualities, such as the timeless theme and print quality,” says Silva. For Canjani, the book stands out for the power of its imagery and the audacity of its layout. “The photos take up almost the whole space and evolve page by page, practically without pauses. It’s a book with a groundbreaking narrative, permeated with a strong sense of strangeness,” he affirms.

According to Silva, Amazônia these days can cost up to R$10,000 in Brazilian second-hand bookstores, and copies of the book can be found at the libraries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), both in New York. The photographer’s work can also be examined in the retrospective George Love: Além do tempo (George Love: beyond time), curated by Zé De Boni, which opened in March at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art (MAM‑SP). The exhibit, on show until May 12, brings together more than 500 photographs, along with documents, letters, and videos, and is the first sizeable exhibition of Love’s work since he passed in 1995.

Project

Photojournalist George Love and the Brazilian landscape in Realidade magazine (nº 14/05256-6); Grant Mechanism Research Fellowship Abroad; Principal Investigator Douglas Canjani de Araujo (PUC-SP); Investment R$8,943.96.

Scientific article

LEITE, M. E. O fotojornalismo experimental de George Love na revista Realidade. Revista Temática. vol. 19, no. 11. 2023.

Book chapter

CANJANI, D. “Imagem e território: A Amazônia nas fotos de George Love.” In: SAKI, M. (ed.). Comunicação em foco: Conexões e fragmentações. São Paulo: Métis Produção Editorial, 2021.