July 11 of this year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of physicist Cesare Mansueto Giulio Lattes (1924–2005). Born in Curitiba to a wealthy immigrant couple from northwestern Italy, César Lattes, as he was best known, was a unique character in Brazilian science. From a very young age, while living in the city of São Paulo, he managed to stand out among a generation of brilliant physicists and mathematicians trained at the newly founded University of São Paulo (USP) in the 1930s and 1940s, including Marcello Damy (1914–2009), Mário Schenberg (1914–1990), and Oscar Sala (1922–2010).

The work he carried out shortly after the end of the Second World War boosted two related fields that use different approaches to study the origin and role of subatomic (smaller than an atom) particles: research into cosmic rays that reach Earth and particle (accelerator) physics.

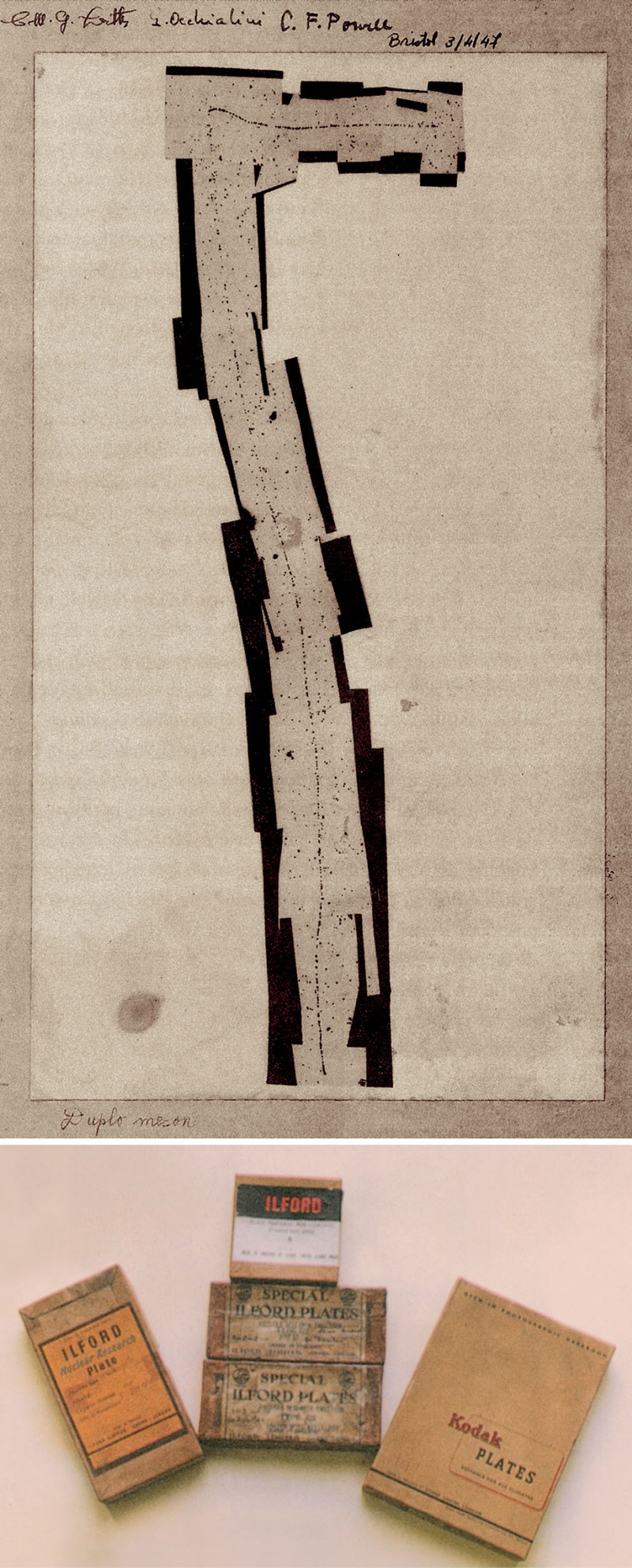

As an investigator of the tiny world hidden inside the atom, he proposed an improvement for nuclear emulsions, a special type of photographic plate used to detect fleeting subatomic particles that only last for fractions of a microsecond. His idea was used to increase the sensitivity of the emulsions, allowing him to see phenomena that others could not, or that they could only see later.

César Lattes personal archiveCésar Lattes (without a jacket) poses with his brother Davide, his mother Carolina, and his father GiuseppeCésar Lattes personal archive

In 1947, while working at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, Lattes codiscovered a new type of subatomic particle produced by cosmic rays hitting Earth: the pi meson (now known as a pion). The primary function of the pion is to hold the atomic nucleus together and thus prevent protons and neutrons from escaping. The improved emulsion plates made it possible to see traces of the particles in records obtained in France and Bolivia. The following year, Lattes was the first to observe the pion itself, this time produced artificially inside a particle accelerator at the University of California, Berkeley (see text). In 1950, the head of his former laboratory in Bristol, British physicist Cecil Powell (1903–1969), won the Nobel Prize in Physics for improvements made to the photographic particle detection method and identification of the pion.

Despite not himself receiving the Nobel Prize, Lattes quickly gained respect and fame. His practical ingenuity led to the Brazilian’s meteoric rise, and the research he carried out in his early career had repercussions at home and abroad. In Brazil, at the height of his popularity, he was a scientific celebrity in the same mold as public health doctors Carlos Chagas (1879–1934) and Oswaldo Cruz (1872–1917). He was the subject of a samba show and was pictured on magazine covers.

With his scientific prestige, he helped found the Brazilian Center for Physics Research (CBPF) in 1949 and supported the creation of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) in 1951 (see text). And he did all this before turning 27. “There is no book on the history of physics in the last century that does not mention the importance of Lattes’s work with the pion,” says physics historian Olival Freire Junior of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), currently scientific director of the CNPq. “Lattes is considered a genius much the same way mathematician John Nash [1928–2015] was.”

Like his American colleague, who won the 1994 Nobel Prize in Economics for his contribution to game theory, Lattes suffered from mental illness. Nash had schizophrenia, a condition that caused hallucinations and at times alienated him from reality. Lattes alternated between episodes of extreme depression and euphoria, a condition that today would likely be diagnosed as bipolar disorder. “He was hospitalized several times due to his mental health, which hindered his career. He might have done more if he had not suffered this problem,” says Antonio Augusto Passos Videira, a philosopher and science historian from Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and collaborating researcher at the CBPF. “But that takes nothing away from the merit of his work.”

César Lattes personal archivePortrait of Lattes aged 19 at his graduation from physics at USP in 1943César Lattes personal archive

Lattes was an enthusiast of experimental physics and often a critic of mathematicians and theorists (Albert Einstein was one of his favorite targets throughout his life). “The only thing that matters is what you can detect or what you can infer from what you detected,” he said in an unpublished interview that is part of the physicist’s collection at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), the last place he worked. “Lattes mastered scientific know-how,” explains Heráclio Duarte Tavares, a science historian from Mato Grosso State University (UNEMAT) who has been studying the physicist’s career.

Although he was one of the first scientists to show the potential of particle accelerators for making discoveries about the subatomic world, Lattes ended up dedicating most of his career to studies of cosmic rays. This was the field in which he began and ended his scientific career.

Before settling in São Paulo in the early 1930s, the Lattes family lived in Curitiba and Porto Alegre, as well as spending six months in Turin, Italy. In São Paulo, César Lattes completed the equivalent of high school at Colégio Dante Alighieri in 1938. The traditional private school, founded by Italian immigrants, still exists to this day. Through family connections, Lattes was able to secure a place on USP’s nascent undergraduate course in physics at just 15 years old.

His father Giuseppe was a foreign exchange manager at Banco Francês e Italiano in São Paulo, and one of his clients was Gleb Wataghin (1899–1986), a Ukrainian-Italian physicist who moved to São Paulo to implement the physics course at USP’s School of Philosophy, Sciences, Languages, and Literature (FFCL) — the predecessor of what is now the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH) — in 1934. The bank where Giuseppe worked was responsible for handling the salary of Wataghin, who studied cosmic rays.

University of BristolMembers of the HH Wills Physics Laboratory at the University of Bristol, headed by Powell (sitting on the left in a suit and tie). Lattes is fourth from the left in the second rowUniversity of Bristol

One day, Lattes Sr. asked the physicist if he would talk to his son, who was interested in science. The young Lattes, who had even considered the idea of becoming an elementary school teacher, spoke with Wataghin and the two hit it off. The rules for enrolling at university were less strict at the time and after passing several academic tests, he was accepted onto the course. Another Italian account holder at the bank, Giuseppe Occhialini (1907–1993), who also taught physics at USP, soon became an inspiration for Lattes Jr.

Lattes was a precocious talent, graduating in 1943 at the age of 19. He did not defend a doctoral thesis, but that did not hold him back. In 1948, after his discovery of the pion, USP awarded him an honorary PhD. After graduating, Lattes spent some time studying cosmic rays in field experiments with two Italian colleagues who also studied physics at USP: Ugo Camerini (1925–2014) and Andrea Wataghin (1926–1984), Gleb’s son. In 1946, he traveled to the United Kingdom and joined Occhialini, who was already at the University of Bristol carrying out research with Powell’s group.

It was the Italian’s second time in the UK. Between 1931 and 1934, he worked at the respected Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Physics, which was led by Patrick Blackett (1897–1974) at the time. Alongside the Brit, he helped improve the Wilson chamber, also known as a cloud chamber, a closed container that uses supersaturated vapor to show the path of ionizing radiation, such as particles from cosmic rays. The pair used the improved device to confirm the existence of the positron — a positively charged antielectron. In 1948, Blackett alone won the Nobel Prize in Physics for this work. An interesting aside: during a stay in Cambridge in the mid-1920s, a young Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967), who suffered from depression, allegedly left a poisoned apple on the desk of Blackett, who was then his supervisor. The scene, fictional or real, appears at the beginning of the 2024 Oscar winner biopic Oppenheimer, which tells the story of the American physicist dubbed the “father of the atomic bomb.”

Reproduction Nature | Alicia IvanissevichTraces left by mesons (above) observed on photographic plates (below) by the Bristol groupReproduction Nature | Alicia Ivanissevich

It was the relationship Lattes established with Occhialini at USP that made it possible for him to go to Bristol in 1946. In the UK, the Brazilian had the chance to observe nuclear emulsions exposed to cosmic rays obtained by the Italian on a 2,800-meter mountain in the French Pyrenees called Pic du Midi. The most sensitive photographic plates seemed to have captured trails produced by particles of the meson class. To be certain of his discovery, Lattes proposed a similar experiment at a higher location in the Bolivian Andes. He believed that on Mount Chacaltaya, at an altitude of 5,421 meters, the chance of recording these particles from cosmic rays with the best-suited version of the photographic plates would be much greater. And he was right.

However, a little-known episode almost put an early end to Lattes’s ascending career. In April 1947, on his way to Bolivia to carry out the field experiment, Lattes had to pass through Brazil. Because the trip was funded by the British, he was advised to buy a plane ticket from a state-owned company, British South American Airways (BSAA). It would have been a long and tiring flight, taking more than a day. After departing from London, there were stops in Lisbon, Dakar, and Natal before arriving in Rio de Janeiro, the final destination.

Lattes did not follow the advice. An official at the Brazilian embassy in London told him that the British aircraft were adapted war bombers and the in-flight service left a lot to be desired. “His contact suggested he travel with the Brazilian airline Panair because they had brand new planes, good food, and attractive flight attendants,” said journalist Cássio Leite Vieira in the book César Lattes – Arrastado pela história (César Lattes – Carried by history), a brief biography published by CBPF in 2017 that can be downloaded for free online. The Brazilian physicist flew by Panair and probably escaped death. The British plane crashed in Dakar. “There are reports that there were no survivors,” wrote Leite Vieira.

After confirming the discovery of the pion in the Bolivia experiment and then at the Berkeley accelerator in 1948, Lattes returned to Brazil with a high reputation. After being involved in the creation of the CBPF and CNPq, he remained in Rio de Janeiro for most of the 1950s. Between 1955 and 1957, He spent time at the universities of Chicago and Minnesota in the US. “He didn’t publish much during this period—probably due to his mental health problems, marked by episodes of depression,” explained Leite Vieira in his book.

In 1960, Lattes returned as professor to the place where his career began: USP. Two years later, he began a major international research project called the Brazil-Japan Collaboration (CBJ), which studied cosmic rays for four decades, primarily at a physics lab set up in Chacaltaya, Bolivia. “Lattes could have stayed abroad,” says Climério Paulo da Silva Neto, a science historian from the UFBA Physics Institute. But he was always a nationalist, he wanted to develop Brazilian science and he prioritized partnerships with South Americans and countries outside Europe and the USA.

César Lattes personal archiveLattes arriving in Brazil in 1948César Lattes personal archive

His return to the institution that trained him was not permanent, however. In 1967, after spending a year at the University of Pisa in Italy, where he worked more closely with geochronology, Lattes transferred to UNICAMP, which had been founded the previous year. He chose to leave USP due to a disagreement over a position as a full professor. He moved to Campinas and took his CBJ research with him. The new university, located in the interior of São Paulo, was where Lattes spent most of his time as a professor and researcher until he retired in 1986. He died in 2005 at the age of 80.

Although he came from a wealthy family, Lattes was always seen as a down-to-earth and approachable person. He loved animals. In interviews, he said he would have liked to have been a veterinarian if he had not become a physicist. There are many stories about one of his dogs, Gaúcho, a pointer who was like his shadow at UNICAMP in the 1970s and 1980s. The dog participated in his classes, attended his lab, and accompanied him on journeys in the car. “My husband [José Augusto Chinellato, a professor at UNICAMP] defended his doctoral thesis with Gaúcho in the room,” recalls physicist Carola Dobrigkeit Chinellato with a smile. Chinellato, a professor at the same university, was also supervised by Lattes during her PhD and like her husband, she went on to investigate cosmic rays.

Friends and colleagues say that although Lattes was generally kind and humble, he was not always an easy person to be around. At times he could be harsh and even unfair. One historic episode was his public attempt to debunk Albert Einstein’s (1879–1955) theory of relativity in 1980. “I remember him calling me and saying he wanted to hold a conference to criticize Einstein’s work,” says physicist Roberto Leal Lobo, director of the CBPF between 1979 and 1982. “I thought the phone call was strange. But there was no way to refuse the request from Lattes, who was the founder of the center.”

Lattes presented his controversial ideas at the CBPF, and he invited the press to the event. “He [Einstein] just got lucky. I think he was mentally ill. But the mentally ill sometimes see things that other people don’t see. He made two lucky guesses: his theory on the photoelectric effect and his theory on black-body radiation, the basis of quantum mechanics. But in everything else I think he’s clueless,” said Lattes in an article published in the newspaper Jornal do Brasil on June 15, 1980.

In a presentation at the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC), physicist Jayme Tiomno (1920–2011), then at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), defended Einstein’s ideas. “Lattes regretted this whole situation later,” says physicist Edison Shibuya, a retired professor from UNICAMP who was supervised by the pion discoverer during his PhD, then studied cosmic rays with him and worked alongside him for almost four decades. “Lattes saw that the measurements he used to test relativity could have been affected by the equipment.”

Lattes was married and had four daughters, three of whom are still alive. None studied physics or became scientists. He also had a brother, Davide, who owned a construction company. At the universities he attended, in addition to his scientific work, he left hundreds of academic descendants: researchers supervised by him in their master’s or doctoral studies who in turn trained new postgraduate students (see text). For a master, there is no greater legacy than the success of their pupils. In April 2024, the Presidency of the Brazilian Republic included Lattes in the Livro dos heróis e heroínas da pátria (Book of national heroes).

Republish