From August 8 to 14, data from the World Health Organization (WHO) shows 7,477 laboratory-confirmed cases of monkeypox virus infection worldwide, an increase of 20% over the previous week. From the beginning of 2022 through August 22, more than 41,000 people from 93 countries have been diagnosed with the disease, with an additional 179 probable cases. There have been 12 recorded deaths, 7 of which occurred in Africa, a continent where monkeypox is endemic in some regions and to which it has mostly been restricted until recently. Two deaths were also confirmed in Spain, one in India, one in Ecuador, and one in Brazil (at the end of July).

“Almost all cases are being reported from Europe and the Americas, and almost all cases continue to be reported among men who have sex with men, underscoring the importance for all countries to design and deliver services and information tailored to these communities that protect health, human rights, and dignity,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, at a news conference in mid-August. These two continents account for 98.5% of monkeypox occurrences this year. With about 3,800 confirmed cases, Brazil is third on the list of countries with the most people infected with the virus. In late July, the WHO declared the disease an international emergency. Soon after, Brazil’s Ministry of Health created an Emergency Operations Center within its public health administration, known as COE Monkeypox, which published a contingency plan aimed at providing health professionals with information for managing the disease.

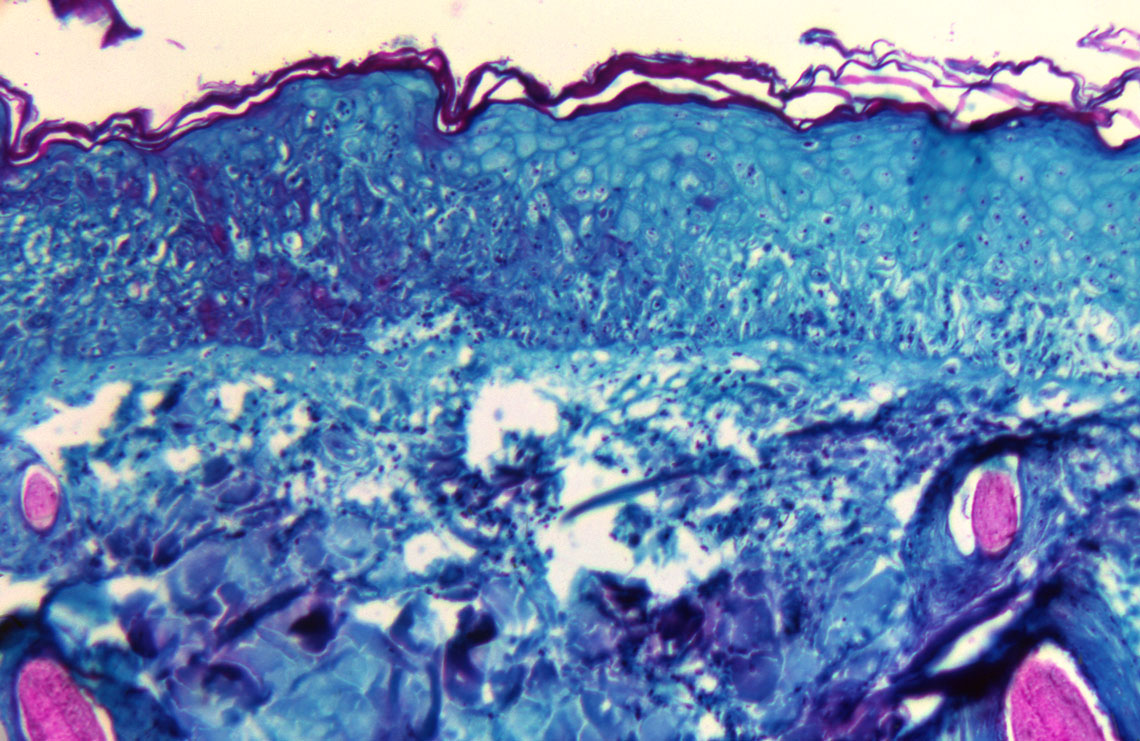

Caused by a pathogen related to the smallpox virus, a disease that was eradicated worldwide in the 1980s, monkeypox is not usually serious and its lethality is relatively low. It is considered to be milder than smallpox. In Africa, the monkeypox mortality rate tends to be higher in children under five years of age, possibly due to a lack of adequate access to health services. After being infected by the virus, it can take 5 to 21 days for the patient to experience any symptoms, such as headache, body aches, fever, and swollen lymph nodes under the jaw or in the back of the neck. The disease’s most uncomfortable clinical manifestation is the formation of pustules, or blisters, which release the virus when they break and can cause marks on the skin. In most cases, the infection clears after two or three weeks of supportive care, such as fever-reducing medication and pain relief, according to the WHO.

There is a specific vaccine against monkeypox, but it is not yet widely available. The Ministry of Health ordered 50,000 doses of the vaccine from a Danish company and the first doses are expected to arrive in September. The possibility still exists that the original vaccine used to eradicate smallpox may provide some protection against the disease. However, recent generations have not had access to the vaccine—which has not been widely used since smallpox was eliminated—and may be more vulnerable.

Monkeypox got its name after the virus was isolated in 1958 in lab monkeys, but in nature, its principal host is rodents. Years later, this virus began to be detected in humans. The first human case was identified in 1970 in Congo, Africa. Until May of this year, when it began to spread globally, the disease was occasionally reported in tourists from other parts of the world who had visited Africa.

Experts are unanimous in saying that the current outbreak of monkeypox has nothing to do with people living with monkeys, although, strictly speaking, it is possible to catch the virus from an infected primate. The disease is transmitted through direct contact with the rashes, crusts, or bodily fluids of a person infected with the virus. This contact may occur through unprotected sexual intercourse, skin injuries, touching genital areas affected with skin lesions, or kisses and even hugs. Objects, tissues, and surfaces that have been touched by infected persons can also pass the virus, in addition to respiratory secretions from patients.

For epidemiologist Eliseu Waldman, from the School of Public Health at the University of São Paulo (FSP-USP), two hypotheses could explain the current outbreak occurring outside Africa, in countries where the virus has never previously been endemic. “It may have been circulating internationally for some time without being noticed, due to its ordinarily benign symptoms and because it can be confused with certain sexually transmitted diseases,” the doctor says. “Another possibility to consider is that the difficulties imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic may have contributed to the monkeypox virus not being identified earlier in people outside Africa.”

According to Waldman, the monkeypox virus has been gradually circulating internationally, with infections increasing outside the group that was most affected thus far. “For now, transmission has occurred predominantly in young adults, in the group made up of men who have sex with men. But the trend is for the virus to become endemic in a large part of the world in people outside this group,” the USP epidemiologist adds. “It’s worth noting that transmission can occur for an extended period, up to four weeks after infection.” Being a zoonosis, a disease transmitted between animals and people, monkeypox is expected to begin being transmitted from humans to pets, a jump that could help spread the virus further. One study in the science journal Lancet reported in mid-August that a man in Paris, France, passed the disease to his dog, apparently the first occurrence of this type of transmission thus far recorded. “We’re going to need good epidemiological surveillance—of a sensitive and timely nature—closely tied to public health services and to research institutes and universities,” Waldman says.

Republish