Just before World Obesity Day on March 4, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced a new international study’s latest estimates of the problem. Based on weight and height information from 222 million people in more than 190 countries, a group of 1,500 researchers, some of them Brazilian, calculated the global progression of obesity over the last three decades. The conclusions, presented in an article published in The Lancet in March, could have a major impact and encourage health authorities and public policy makers to act urgently.

The most alarming finding is that there are currently 1.04 billion people with obesity worldwide, meaning that one in every eight of the planet’s inhabitants (12.5%) is well above what is considered a healthy weight. This group of the population is at a higher risk than other individuals of developing diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, certain forms of cancer, and of dying young.

Between 1990 and 2022, the world’s population grew by 51%, rising from 5.3 billion people to 8 billion. In the same timeframe, the total number of individuals with obesity increased by 360%, from 221 million to the current 1.04 billion—of which 159 million are children and adolescents.

The prevalence of obesity among adults has increased in almost every country on Earth. In relative terms, the average frequency doubled among women (from 8.8% to 18.5%) and tripled among men (from 4.8% to 14%). The global trend, which has been observed among adults since the 1990s, is also now affecting children and adolescents. The increase was approximately fourfold in the 5–19 age group. The proportion of obese female children and adolescents increased from 1.7% in 1990 to 6.9% in 2022. Among boys, it jumped from 2.1% to 9.3%.

The rise in obesity in absolute and relative numbers was accompanied by a significant reduction in people who are underweight. The total number of people whose weight was below a healthy level decreased from 649 million in 1990 to 532 million in 2022.

With the simultaneous rise in obesity and drop in number of people who are underweight, being overweight has become the world’s leading cause of malnutrition (an imbalance between the calories and nutrients that the body needs and those that it obtains). The problems are two sides of the same coin. Being underweight leads to health problems due to an absence of what the body needs. Obesity occurs due to an excess. There are now more obese people than underweight people in every region of the planet except Southeast Asia.

“It is very concerning that the obesity epidemic that was evident among adults in much of the world in 1990 is now mirrored in school-aged children and adolescents. At the same time, hundreds of millions are still affected by undernutrition, particularly in some of the poorest parts of the world,” said epidemiologist Majid Ezzati of Imperial College London, coordinator of the study, in a press release. “To successfully tackle both forms of malnutrition it is vital we significantly improve the availability and affordability of healthy, nutritious foods.”

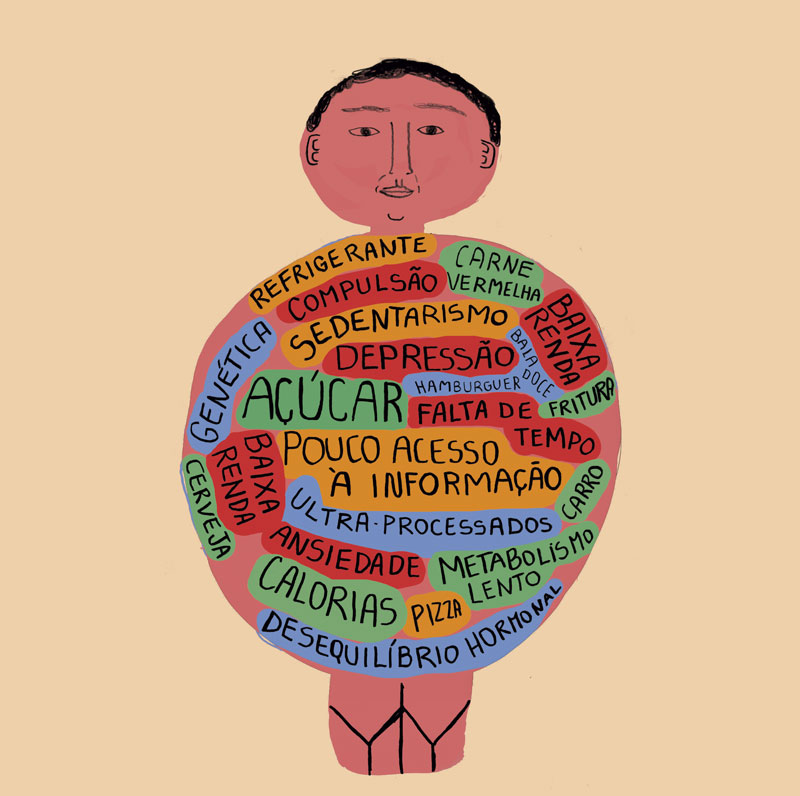

For some time now, obesity has been considered a chronic and multifaceted disease. On an individual level, it results from a combination of genetics and living conditions. There are a small number of genes known to make a person gain weight when altered. But there are more than 300 that regulate the accumulation and consumption of energy. A person may even have genetic characteristics that favor weight gain, but gain little weight if they maintain a healthy diet and exercise regularly, for example. Or they may not have the genetic variants that encourage the accumulation of fat, but they gain weight anyway because they eat too much or only have access to high-calorie foods.

The WHO and other health agencies generally use the body mass index (BMI) to classify whether or not an adult is in the ideal weight range—in children and adolescents, the criterion is different, based on how much their weight deviates from ideal growth curves. A person’s BMI is calculated by dividing their weight—or mass (muscles, bones and fat)—by the square of their height. Individuals are then classified into one of four categories: underweight (BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2); healthy weight (BMI greater than 18.5 kg/m2 and less than 25 kg/m2); overweight (BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2); or obese (BMI greater than 30 kg/m2). According to the index, a person who is 1.7 m tall will be underweight if they weigh less than 53.5 kg and obese if they weigh more than 86.7 kg.

It is a useful tool for estimating health at a populational level because it is based on two easy-to-obtain measurements (weight and height). It does not, however, always indicate an individual’s real health status because it does not take into account what proportion of their mass is fat (a person can have a BMI greater than 25 because they are very muscular) or where the fat is concentrated (fat stored between the organs is more harmful than fat under the skin). Doctors and nutritionists therefore use other indicators, such as waist circumference and analysis of the blood fat levels, to estimate an individual’s health.

Experts are also concerned that more people are becoming obese at an earlier age. The younger they become obese, the longer a person remains at a greater risk of developing associated diseases, although there are healthy obese people. “Obesity is becoming more severe, early, and prolonged. It’s almost a life sentence,” says Brazilian pediatrician and nutritionist Mauro Fisberg of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). One of the authors of the article published in The Lancet, Fisberg says the population is now more likely to remain overweight for longer or to become obese. “Some children who are overweight in the prepubertal years no longer experience the weight loss that used to be characteristic of puberty,” he says.

Experts are also concerned that more people are becoming obese at an earlier age. The younger they become obese, the longer a person remains at a greater risk of developing associated diseases, although there are healthy obese people. “Obesity is becoming more severe, early, and prolonged. It’s almost a life sentence,” says Brazilian pediatrician and nutritionist Mauro Fisberg of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). One of the authors of the article published in The Lancet, Fisberg says the population is now more likely to remain overweight for longer or to become obese. “Some children who are overweight in the prepubertal years no longer experience the weight loss that used to be characteristic of puberty,” he says.

In reality, the situation described in The Lancet may be even worse. And if nothing is done to drastically change things, the problem could continue to worsen over the next decade. The 2024 World Obesity Atlas, published by the World Obesity Federation (WOF) in March, estimates that 42% of the world’s adult population was overweight in 2020—with around 1.39 billion people overweight and 810 million obese. The document projects that the figure will reach 54% by 2035, with 1.77 billion people overweight and 1.53 billion obese, which would cost the global economy US$4 trillion per year in healthcare expenses and lost productivity.

Brazil finds itself in an intermediate situation, although the proportion of people with obesity is much higher than the global average. With the increase in weight gain over recent decades, the number of obese Brazilian children and adolescents rose from 3.1% (including both sexes) in 1990 to 14.3% among girls and 17.1% among boys in 2022. In adults, it rose from 11.9% to 32% among women and from 5.8% to 25% among men. The country is currently 54th in the world in terms of childhood obesity and 65th and 70th for men and women respectively.

In Brazil, the nutritional transition, marked by a decline in malnutrition and a simultaneous increase in people being overweight and obese, began well before the 1990s. At the University of São Paulo (USP), physician and epidemiologist Carlos Augusto Monteiro and his colleagues identified its inception in the 1970s (see interview). In the following decade, excess weight began to emerge as a public health concern for the adult population.

Just like in the rest of the world, the problem is expected to get worse in Brazil over the coming years. Based on weight and height data from 730,000 Brazilian adults collected through telephone interviews between 2006 and 2019, UNIFESP epidemiologist Leandro Rezende and colleagues calculated the recent evolution of obesity in the country: the proportion of people with a BMI greater than 30 rose from 11.8% in 2006 to 20.3% in 2019, according to the results published in Scientific Reports in 2022. The relative increase in prevalence was greater among women, young adults, Black people and minority groups, and people with an intermediate level of formal education (8 to 11 years of schooling). The group projects that by 2030, 68% of Brazilian adults will be overweight, with 29.6% obese.

In a review article published in Nature Metabolism in March, researchers from USP, the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and the National Autonomous University of Mexico listed seven social, economic, and cultural factors that may play a predominant role in the rising number of people who are overweight or obese, especially in Latin America. These include exposure to certain types of food, social inequality, and limited access to scientific knowledge. “There are genetic factors involved in the onset of obesity, but a person’s circumstances are the main determinant of the problem,” says Sandra Ferreira Vivolo, an endocrinologist from USP’s School of Public Health and lead author of the article. “This factor has a close relationship with socioeconomic status, which influences access to education, adequate nutrition, healthcare, and safe physical activity.”

Environmental conditions are even capable of modifying a person’s risk of developing obesity from before birth. They shape gene activation patterns in adults—without altering the genes themselves—and these patterns can be passed onto children, a phenomenon called epigenetics. “In animal studies, it has been shown that exposing the parents to poor nutrition, especially the mother during pregnancy, has an impact on the offspring, who tend to gain more weight when subjected to a diet rich in fat,” says UNICAMP biologist Marcelo Mori, corresponding author of the study.

In an attempt to change the global situation, several countries, including Brazil, signed up to the WHO Acceleration Plan to Stop Obesity at the 75th World Health Assembly, held in 2022. The plan includes actions such as implementing regulations to protect the population from the harmful impacts of marketing by the food industry and establishing nutritional labeling policies (including front labels) and fiscal policies (such as taxes and subsidies that promote healthy diets).

In Brazil, the Brazilian Dietary Guide, which provides official dietary guidelines, established more than a decade ago that “adequate and healthy food is a basic human right that includes guaranteeing permanent and regular access in a socially fair way,” proposing that “natural or minimally processed food, in wide variety and predominantly of vegetable origin, is the basis of the diet.” The problem, however, still appears far from being resolved.

In a qualitative study published in the journal Cadernos de Saúde Pública in March, a team led by nutritionist Larissa Loures Mendes of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) interviewed residents of favelas in Brazil’s Southeast to assess how they perceive food access—it is estimated that 16 million Brazilians live in 11,000 favelas across the country. Based on the responses, the researchers found that the favelas lack many of the resources and fundamental elements needed for an adequate and healthy diet. There is an absence of information about food, income is insufficient, and there are very few establishments that sell healthy foods at affordable prices.

This situation may be beginning to change, however. In March, the federal government issued a decree establishing the composition of a new basic food hamper for government programs that primarily contains natural or minimally processed food, in addition to culinary ingredients. The new hamper will contain beans, cereals, roots, and tubers; fruit, vegetables, and greens; chestnuts and walnuts; meat, eggs, milk, and cheese; sugar, salt, oil, and fats; and coffee, tea, herbs, and spices.

Modern weight-loss drugs and stomach-reduction surgeries may be effective approaches for specific and severe cases, but they are not the best method for tackling the problem at a population level. “For developing countries like ours, the most effective strategy is prevention,” says Vivolo. “It is better to change the social and cultural determinants of obesity than to rely on pharmacological or surgical interventions,” adds Rezende.

Projects

1. The reciprocal action of the immune system and metabolism as the main determinant of the aging process (nº 21/08354-2); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Marcelo Alves da Silva Mori (UNICAMP); Investment R$4,055,356.61.

2. CMPO – Multidisciplinary Center for Research into Obesity and Associated Diseases (nº 13/07607-8); Grant Mechanism Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs); Principal Investigator Licio Augusto Velloso (UNICAMP); Investment R$49,186,229.92.

Scientific articles

NCD RISK FACTOR COLLABORATION. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet. Vol. 403, no. 10431, pp. 1027–50. Mar. 16, 2024.

ESTIVALETI, J. M. et al. Time trends and projected obesity epidemic in Brazilian adults between 2006 and 2030. Scientific Reports. July 26, 2022.

FERREIRA, S. R. G. et al. Determinants of obesity in Latin America. Nature Metabolism. Mar. 4, 2024.

ROCHA, L. L. Percepção dos residentes de favelas brasileiras sobre o ambiente alimentar: Um estudo qualitativo. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. Mar. 2024.