“Pedro, this bug is different.” Vinicius Lopez was still studying biology in Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, when, in early 2017, he sent a message along with photos of male and female wasps of an apparently unknown species to biologist Pedro Bartholomay. At the time, Bartholomay was pursuing his doctorate at the National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA) in Manaus, Amazonas, and specializing in hymenoptera—an order of insects that includes bees, ants, and wasps.

Lopez had received the images from biology student Herbeson Martins, who had photographed the wasps in a preserved Caatinga (semiarid scrublands) area on the campus of the Federal University of Vale do São Francisco (UNIVASF) in Petrolina, Pernambuco. The exchange of information and collaborative effort among the three friends ultimately led to a study on this unique group of wasps that possess rare evolutionary features. They are the first wasps in Brazil to exhibit ultra-black spots or stripes that reflect only 0.5% of light. Other animals—such as butterflies, fish, birds, and even panda bears—also feature white, black, or ultra-black markings that help them blend into their environments and confuse predators.

Upon receiving Lopez’s message, Bartholomay recalled a specimen of a female from this seemingly new species that was kept at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR). It had been collected in 2012 from the municipality of Russas in Ceará by biologist Kevin Williams, from the California Department of Food and Agriculture, in the United States. Williams had classified it as a probable new species, temporarily named Goncharovtilla oblomovi, but was unable to proceed with further description due to the lack of additional specimens.

Through DNA analysis, Bartholomay, Lopez, and Martins confirmed that the specimens collected in Pernambuco and Ceará were indeed a unique species. They then set about composing a detailed description, in collaboration with Williams and Roberto Cambra from the University of Panama, who had also discovered a new species in that country. The comprehensive account of the two new genera—each with one species—grouped within the Mutillidae family, was published in November 2024 in the scientific journal Zootaxa.

Light Filters

During his doctorate, completed in 2024 at the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Philosophy, Sciences, and Languages and Literature (FFCLRP-USP), Lopez used a spectrometer—a device that measures the light reflected from an object—to measure the intensity of the black coloration in G. oblomovi and Traumatomutilla bifurca, another species of wasp from the Caatinga, also found in the Cerrado (wooded savanna biome). “The black of both species was more intense than the black used to calibrate the equipment,” noted Lopez, who has been conducting a postdoctoral internship at the Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM) since 2024.

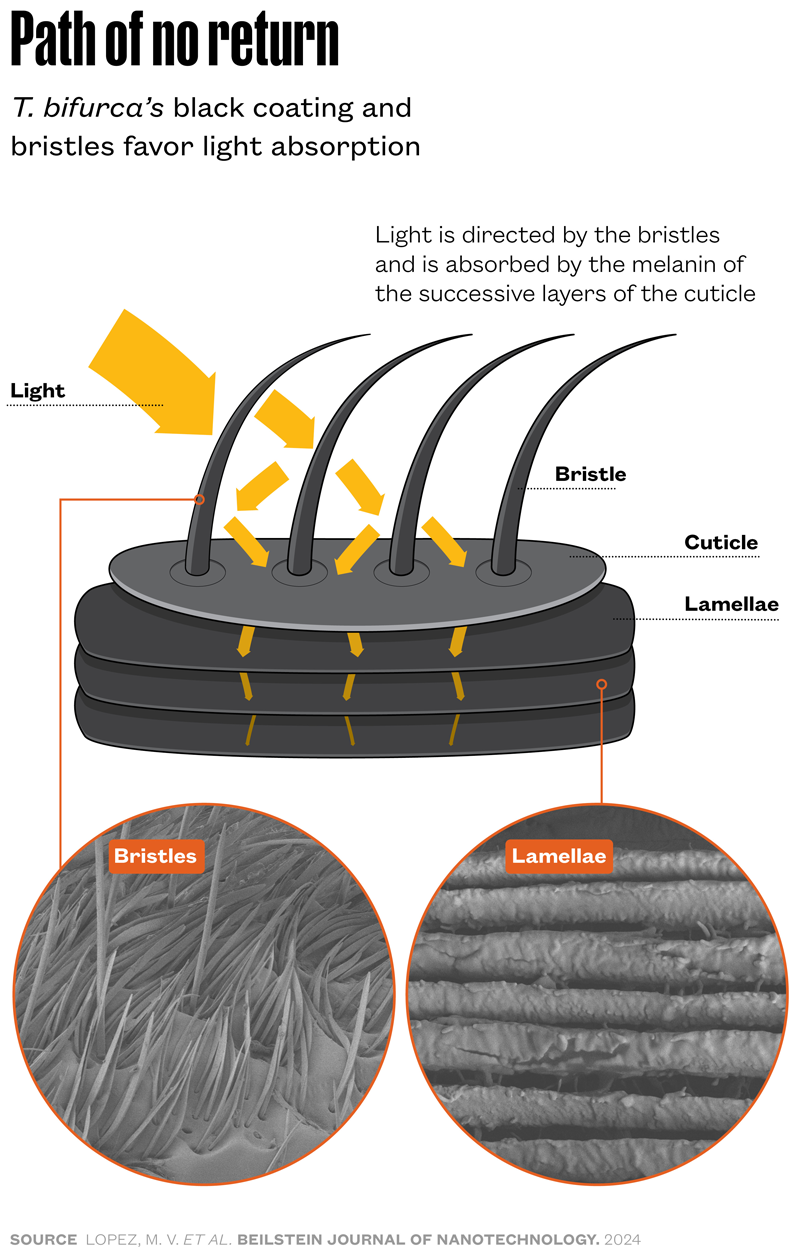

T. bifurca reflects so little light because of the structure of its armor, also known as the cuticle. As detailed in a December article in the Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology, the bristles on the wasp’s armor direct light into layers, or lamellae. In each layer, the pigment melanin absorbs the light, and the remaining light passes to the next layer, where it is also absorbed, successively (see infographic).

The dark color helps keep the wasps’ bodies 2 degrees Celsius below the outside temperature, as demonstrated experimentally by Brazilian and German biologists. “The idea that black heats up more than white is not always correct,” says Lopez. “Dark colors can result from the absorption of light by structures that dissipate a lot of heat, while light colors come from surfaces that absorb little light but retain almost all the heat they receive, as they emit very little radiation.” According to Lopez, the white and black parts of the wasps exhibit the same thermal behavior, as they are made up of the same type of cuticle. In vultures, however, the black coloring gets very hot and helps kill pathogens from the carrion they consume.

“To understand the effects of ultra-black coloring on camouflage, we would need to know the predators, because it all depends on how the hunter locates the prey,” comments biologist Alexandre Palaoro from UFPR, an expert in animal behavior. He explains that black is associated with the temperature control mechanism, which directs light and heat to specific regions of the body. “The abdomen of insects is notoriously thin and dissipates heat very efficiently.”

Pedro Igor Monteiro / iNaturalistIn birds, such as the yellow-headed vulture, the heat generated by black coloring helps eliminate microorganismsPedro Igor Monteiro / iNaturalist

Tough Females

Martins, who has been pursuing a PhD at the Institute of Biosciences at the University of São Paulo (IB-USP) since 2024, observed that both male and female wasps are solitary, more active in the early morning and late afternoon, and equally covered in black and white spots. They both produce a squeaking sound, which has earned them the popular name “squeaky ants.” When threatened, the wasps vibrate two plates under their abdomen, generating friction that produces the squeak, a defense mechanism intended to ward off potential danger.

There are also significant differences between the sexes. Males have wings, can fly, lack a sting, and measure between 4 and 9.5 millimeters (mm) in length. They attempt to mate with females, even those of other species, and die after copulating. Females, on the other hand, are flightless, possess a painful stinger, are larger, ranging from 6 to 10 mm, and refuse further mating after fertilization. They parasitize bee nests, laying their eggs there. Additionally, the armor of the females is harder than that of the males. “They are little armored tanks,” Lopez compares.

Researchers from Hanover College and the universities of Missouri and Tennessee in the United States have concluded that the females of other wasp species in the Mutillidae family, each exhibiting ultra-black spots, “appear to be almost immune to predation,” as reported in a May 2014 article in Ecology and Evolution. This conclusion came from an experiment in which wasps were offered to lizards, birds, frogs, and small mammals. Two birds attempted to peck at a wasp after several unsuccessful attacks, and only one frog ate it, but then regurgitated it, blinking a lot, which indicated pain. The second time it was offered, the frog refused.

The story above was published with the title “The advantages of being ultra-black” in issue in issue 349 of march/2025.

Scientific articles

DAVIS, A. L. et al. Diverse nanostructures underlie thin ultra-black scales in butterflies. Nature Communications. Vol. 11, 1294. Mar. 10, 2020.

GALL, B. G. et al. The indestructible insect: Velvet ants from across the United States avoid predation by representatives from all major tetrapod clades. Ecology and Evolution. Vol. 8, no. 11. May 18, 2018.

LOPEZ, M. V. et al. Ultrablack color in velvet ant cuticle. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology. Vol. 15, pp. 1554–65. Dec. 2, 2024.

WILLIAMS, K. A. et al. Two new genera of Neotropical Dasymutillini (Hymenoptera, Mutillidae, Sphaeropthalminae): Goncharovtilla gen. nov. from Brazil and Dasyphuta gen. nov. from Panama. Zootaxa. Vol. 5538, no. 2. Nov. 14, 2024.