At the end of January, two articles were published almost simultaneously by members of the international DELVE collaboration in The Astrophysical Journal. Brazilians who are part of the DELVE collaboration participated as coauthors in both studies and reported the discovery of two extremely small galaxies with very low luminosity, or ultra-faint galaxies as astrophysicists call them. The smallest, with around 2,000 stars, was named Aquarius III and the other, with roughly double the stars, Leo VI. The names refer to the constellations in which the galaxies are located, Aquarius and Leo, respectively.

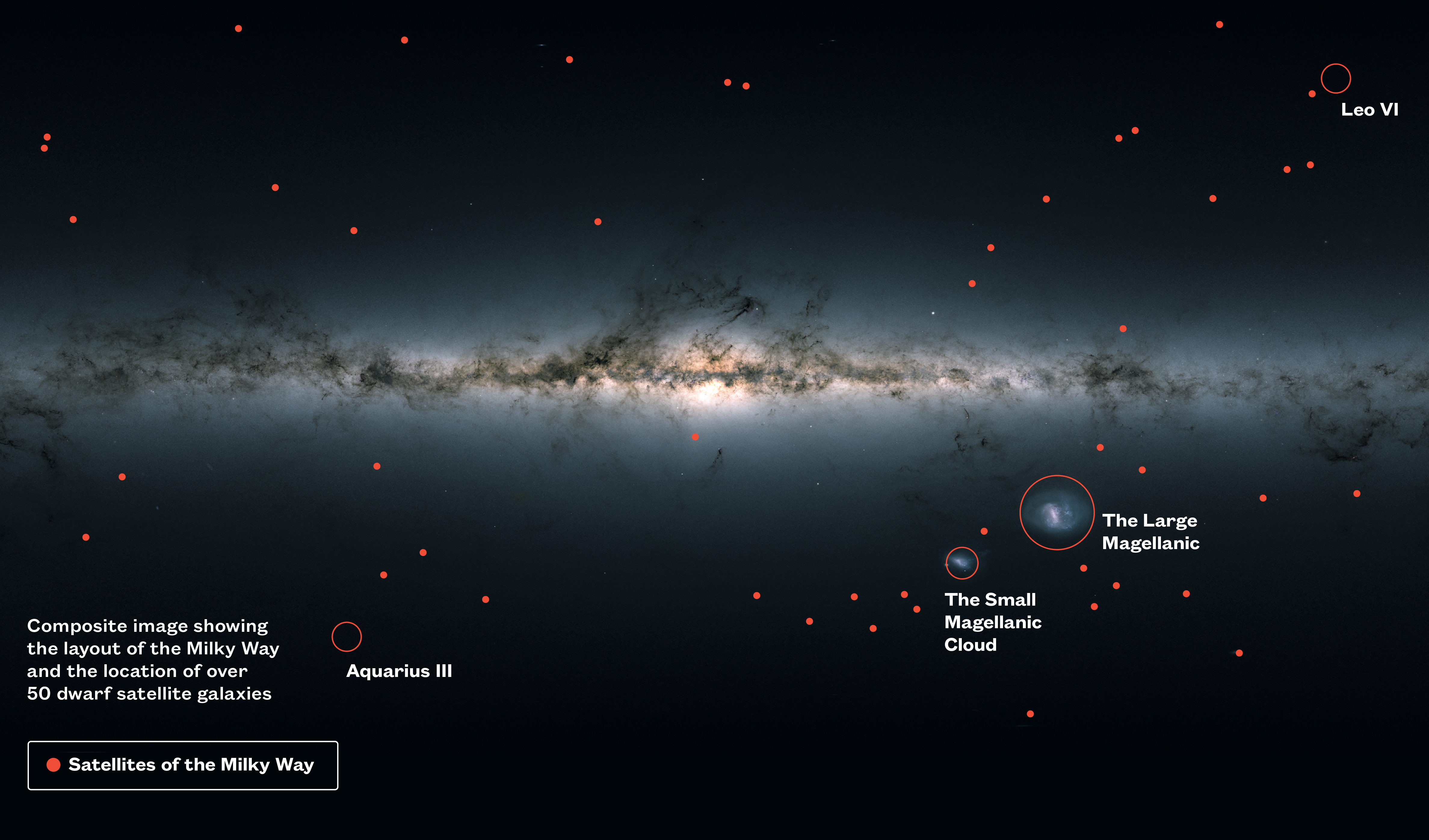

Aquarius III and Leo VI are two dwarf satellite galaxies of the Milky Way. Like the moon in relation to the Earth, they orbit around the Milky Way, which is made up of a population estimated at between 100 billion and 400 billion stars. The gravitational force resulting from the immense mass of our galaxy attracts and keeps them in orbit around it. Until the beginning of this century, astrophysicists knew of 11 dwarf galaxies considered satellites of the Milky Way. In the past two decades, the introduction of more powerful and sensitive telescopes and observational instruments has enabled the identification of smaller and fainter galaxies around the Milky Way. With the discovery of Aquarius III and Leo VI, this number reaches 65, of which 51 have had this status confirmed (see above, the location of these galaxies in relation to the layout of the Milky Way).

“Studying dwarf galaxies is a way of trying to understand the formation and evolution of the Milky Way,” says astrophysicist Guilherme Limberg, one of the authors of the two articles. “Aquarius III is the smallest known satellite galaxy of the Milky Way and one of the smallest galaxies ever discovered.” In October 2024, while he was a FAPESP scholarship beneficiary, he defended his PhD thesis on the topic at the Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences of the University of São Paulo (IAG-USP) and is currently doing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Kavli Institute of Cosmological Physics of the University of Chicago, USA.

The interaction of the Milky Way with these dwarf satellite galaxies is one of the parts that interests researchers the most. “For example, we know that the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy is, little by little, being engulfed by our galaxy,” comments astrophysicist Clécio De Bom, of the Brazilian Center for Research in Physics (CBPF), another participant of the DELVE collaboration and coauthor of the two articles. In the case of Aquarius III, there are signs that it will one day be destroyed due to the tidal forces of the Milky Way—a secondary effect of our galaxy’s immense gravitational force, capable of breaking celestial bodies apart. For now, the available data does not allow them to predict whether Leo VI will share the same fate.

Any reasonably sized galaxy among the billions in the Universe may be surrounded by dwarf satellite galaxies. The three largest galaxies in the so-called Local Universe (Andromeda, the Milky Way, and Triangulum) are surrounded by smaller counterparts. The Local Universe is Earth’s cosmic neighborhood, a region of space with a radius of approximately 1 billion light-years, 20,000 times larger than the Milky Way. Although the name suggests small star formations, dwarf satellite galaxies come in a variety of sizes. Some are of considerable size.

ESORelatively sparse stars form the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy, a satellite of the Milky WayESO

Such is the case with the two Magellanic Clouds, the Large and the Small. Like Aquarius III and Leo VI, they are classified as dwarf satellite galaxies of the Milky Way, despite being much larger than the two structures discovered this year. The estimated mass of the Large Magellanic Cloud, which contains around 10 times more stars than its smaller counterpart, represents between 10% and 20% of the Milky Way’s mass. The two clouds are so large that, just like the Milky Way, they can be seen with the naked eye in the Southern Hemisphere. They have been known to the Indigenous peoples of South America since time immemorial and to the Europeans since the age of Discovery.

The majority of dwarf satellite galaxies have a diffuse, poorly defined shape. They barely look like a concentration of stars. In their most evident forms, they display a light halo of denser color at their center, dotted with a few brighter stars. For many dwarf galaxies, like the two recently discovered satellite galaxies of the Milky Way, there are no clear images. They generally look nothing like the beautiful large spirals, such as the Milky Way, with its denser central bulge and two stellar arms.

Galaxy or star cluster?

The two new dwarf satellite galaxies were initially identified by the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), a powerful camera installed in the Blanco telescope, in Cerro Tololo, in the Chilean Andes. Since 2012, DECam has been used in surveys of the southern sky, such as the Dark Energy Survey (DES), and more recently in the DELVE collaboration. Once a structure with potential to be classified as a dwarf satellite galaxy of the Milky Way is observed, astrophysicists must eliminate a troubling doubt. Clusters of a few thousand stars can form into a small cluster star, a simpler structure, or a small dwarf galaxy, a more complex formation.

The way to differentiate one type of structure from another is by looking at the characteristics of its star population. “The stars in the clusters were formed simultaneously, from a single event that took place in a cloud of gas and dust,” explains Limberg. “They have the same chemical composition and evolutionary history.” In a galaxy, the stars tend to be more diverse, originating from more than one formative event, with a variety of ages and compositions.

To discover whether there is more than one generation of stars, researchers need to determine the level of metallicity of some celestial bodies within the candidate galaxy. Roughly speaking, when there are stars with different levels of metal content, it suggests it is a galaxy, made up of different stellar populations. In a star cluster, the metallicity is the same throughout its stars, since in this case, all the stars were formed at the same time.

ESA / Gaia / DPACThe Large (left) and Small Magellanic CloudESA / Gaia / DPAC

The metallicity of six stars from the Aquarius III galaxy and nine from Leo VI were determined based on measurements made by the spectrograph of the Keck Observatory, in Hawaii. This instrument breaks down the light from stars into its different wavelengths, which enables the chemical composition of the stars to be deduced. The brightest star of Aquarius III presented similar chemical characteristics to the rare stars found in the halo of the Milky Way.

“This is extremely interesting,” comments Brazilian astrophysicist Vinicius Placco, of NOIRLab, a research center funded by the USA’s National Science Foundation (NSF). “But we need high-resolution measurements to confirm these chemical abundances and then we can speculate about the origin of the star.” Placco is one of the coauthors of the article about Aquarius III and also participates in the DELVE survey. In these studies, astrophysicists also provide data about the motion and location of around 10 stars from each dwarf galaxy based on observations with the European space telescope Gaia.

The discovery of over 50 dwarf satellite galaxies of the Milky Way in the last 20 years reduces a point of friction between theory and astronomical observations. According to cosmological models, the Milky Way and other similar galaxies should have many dwarf galaxies in their orbit, as many as a few hundred of these satellites. These predictions are based on the fact that 85% of the matter in the Universe is composed of cold dark matter, which is invisible and of unknown nature. The other 15% is made of normal baryonic matter, which gives shape to the visible structures of the Cosmos.

The existence of dark matter is deduced based on its gravitational effect on the structure of celestial objects. The gravity produced by normal matter is incapable of explaining the interaction between the visible structures of the Cosmos and their distribution. Therefore, compared to normal matter, there must be an almost six times greater quantity of an unknown type of matter—dark matter—to explain the known Universe.

The theory predicts the existence of sub-halos of dark matter surrounding large galaxies, such as the Milky Way, which could lead to the formation of stars and the emergence of many dwarf satellite galaxies. It is true that these small structures are difficult to observe, an obstacle that has only recently begun to be overcome. “In the last six years, the DELVE project has discovered six dwarf galaxies orbiting our galaxy,” says De Bom. “But the problem of the lack of satellite galaxies has not yet been fully resolved by us or by any other initiative.”

The story above was published with the title “Neighbors in orbit” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Project

The chemodynamical structure of the galactic halo (nº 21/10429-0) Grant Mechanism Direct Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Silvia Cristina Fernandes Rossi (USP); Beneficiary Guilherme Limberg; Investment R$243,432.29.

Scientific articles

CERNY, W. et al. Discovery and spectroscopic confirmation of aquarius III: A low-mass milky way satellite galaxy. The Astrophysical Journal. Jan. 23, 2025.

TAN, C. Y. et al A pride of satellites in the constellation Leo? Discovery of the Leo VI milky way satellite ultra-faint dwarf galaxy with DELVE early data release 3. The Astrophysical Journal. Jan. 24, 2025.