In October 2010, Brazilian astronomer Duilia de Mello was preparing to give a talk on stellar formations located outside the galaxies at the Carnegie Institute in US capital Washington, DC. Before the presentation, she was very moved to see Vera Rubin (1928–2016) and Nancy Roman (1925–2018) in the audience—two prominent astronomers of the American scientific community. Both asked questions at the end of the talk, with Rubin asking if Mello knew if the galaxies presented were dwarfs, and how much dark matter they had.

“It was a very good question, and we have no answer to date,” recalls Mello, then practicing at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and currently vice dean at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. The good news is that the answers to those questions may come from two large observation devices set to begin operating in the coming years: the Vera Rubin Observatory, an initiative worth almost US$500 million being built in Chile, and the Nancy Roman Space Telescope, a NASA enterprise costing more than US$3.2 billion. This is the first time that astronomy projects of this scale have been named for researchers.

Under construction at Cerro Pachón, in the Chilean Andes, the Rubin Observatory, which up to 2020 was known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, is set to go online at the end of 2025. During its first 10 years of activity there will be four priorities: to compile an inventory of the Solar System, map the Milky Way, localize visible transitory events such as stellar explosions, and investigate dark energy and, primarily, dark matter.

The change in the Observatory’s name is a way of recognizing the research conducted by Rubin, which provided strong evidence of the existence of dark matter. Working alongside astronomer Kent Ford, Rubin studied galaxies close to the Milky Way while working at the Carnegie Institute in the late 1970s. On observing that peripheral stars rotated around the galaxy at a velocity similar to that of more central stars, they found it odd and decided to investigate the phenomenon.

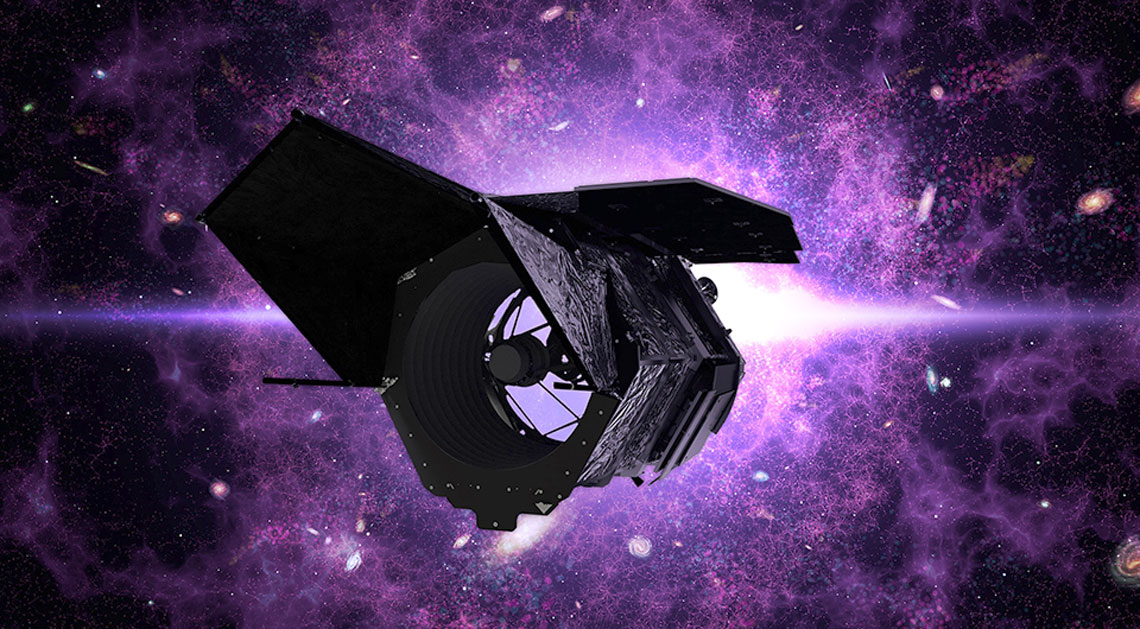

GSFC / SVS Illustration of the Roman Space Telescope, a US$3.2-billion NASA project forecast to begin operation in 2027GSFC / SVS

“It is to be expected that more central stars rotate faster, with peripheral ones moving more slowly. That’s what happens with the planets of our galaxy,” explains Puerto Rican astrophysicist Karín Menéndez-Delmestre, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). The difference in velocity is due to the gravitational force exercised by the mass of all the celestial bodies inside the galaxy. However, in their studies Rubin and Ford noted that the total mass of the visible objects in the galaxies observed was not sufficient to justify the accelerated movement of marginal stars.

Their starting point was a notion previously proposed by other astronomers: similar anomalies observed in the movement of other stars could be explained if the universe contained invisible, as well as luminous, material. Using precise systematic measurements, Rubin and Ford demonstrated, without leaving any room for doubt, that the galaxies have many times more dark mass than is visible.

For all that is known of the existence of this type of hidden material due to its gravitational effect on the visible part of the universe, its constituent particles are as yet unknown. To provide clues on this and other open questions, the Reuben Observatory will register clear images of a piece of the sky using the biggest astronomy camera ever built, with 3,200 megapixels, and a telescope with a lens of 8.4 meters (m). Moreover, it will return to the same part of the sky every three nights, exploring brief events, objects that shine weakly, or those a great distance away. The observatory is funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and Department of Energy (DOE).

The background of NASA’s Roman Space Telescope is similar. Up to March 2020 it was known as the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope, or WFIRST. NASA then decided to rename it in honor of Nancy Roman. Having been the first female researcher to head the space agency’s astronomy department, at the beginning of the 1960s, she is considered the first woman to have held an executive post at NASA.

RubinObs / NSF / AURA / H. StockebrandUnder construction in Chile, the Vera Rubin Observatory, an initiative of almost US$500 million, is set to be inaugurated in 2025RubinObs / NSF / AURA / H. Stockebrand

Roman built her academic career before joining the institution. Despite having made important discoveries on the classification of stars and their orbits in the Milky Way, she felt poorly paid and disenfranchised as a woman in her endeavors to become a senior researcher. For this reason she accepted other jobs, one of which was at NASA, where she was responsible during almost 20 years for managing the program that would give rise to the Hubble Space Telescope, named in tribute to the work of American astronomer Edwin Powell Hubble (1889–1953). Roman is often remembered as the “mother” of Hubble—launched into orbit in 1990 and still operational today—for her efforts in making the project happen.

The Roman telescope is forecast for launch in 2027, and has a lens of 2.4 m in diameter, equal to that of the Hubble. It will be capable of studying dark energy (which moves the expansion of the universe) and dark matter, exoplanets, and objects or phenomena that can be captured using infrared light, but are not visible to the human eye. One of the differences between the Roman and the Hubble will be the camera’s field of vision: the Roman’s will be 100 times bigger, capturing more elements in the infrared spectrum.

Duilia de Mello says that recognition of Rubin and Roman is of paramount importance. “As with the Hubble telescope, people will look up the names and know who they were and what they did. It is a way of showing that such important women came to be honored,” she states. Menéndez-Delmestre shares this opinion: “Names that were previously left somewhat on the margins are being brought to the forefront of history. For example, many researchers wonder why Rubin did not win the Nobel prize.”

According to astrophysicist Rita de Cássia dos Anjos, of the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), this recognition may also help to increase the number of female researchers in the area. 2023 data from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) indicate that in Brazil there are 19,000 researchers in the wider exact and earth sciences field, which encompasses astronomy and astrophysics. Of these, 6,800 are women, of which 1,800 Black, and 68 Indigenous researchers.

“Without this recognition, how can we motivate girls to embark upon scientific careers? This type of action and the emergence of awards dedicated to women are some of the possible pathways,” says dos Anjos.

Name of the world’s biggest space telescope in recent controversy

Since the mid-2010s, members of the global astronomical community have criticized the choice of American director James Webb (1906–1992) for the name of the US$10-billion super space telescope launched by NASA in December 2021. He was the second director of the fledgling American space agency, holding the post between 1961 and 1968.

Webb had been publicly accused of having endorsed or been aware of the mass dismissal of and discrimination against LGBTQIA+ staff some 15 years before heading up NASA, when he was State Department undersecretary during the administration of US President Harry Truman (1884–1972). However, a background investigation of the agency, published in 2022, found that there was no direct evidence that Webb participated in the dismissals, and his name was maintained for the telescope.

Not all were satisfied with the decision. Certain scientific journals, such as the British Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, came to prohibit the use of the name James Webb to designate the telescope for a brief period in articles published in its editions, advocating for the use of JWST only. Subsequently, with the disclosure of more NASA documents about Webb, the periodical took a more flexible stance and currently accepts both ways of referring to the observation device, although they prefer the acronym JWST.