At first glance, oncillas may appear indistinguishable from one another. But not to Tadeu de Oliveira, a biologist at the State University of Maranhão (UEMA). Having examined thousands of images and videos captured by camera traps, and having observed these creatures both in the wild and in captivity, Oliveira—along with fellow UEMA researcher Lester Fox-Rosales and 40 other coauthors—has recently redefined the conceptual and geographical boundaries of the species Leopardus tigrinus based on morphological, ecological, and geographical patterns, in a paper published in January in Scientific Reports.

Initially described in 1777 based on a specimen collected in French Guiana, over the centuries the species has been classified into four subspecies: Leopardus tigrinus tigrinus, L. t. pardinoides, L. t. oncilla and L. t. guttulus. In 2013, the southern tiger cat was distinguished as a separate species, L. guttulus, through the genetic research of Tatiane Trigo, a geneticist who demonstrated the absence of genetic exchange with other species. Trigo conducted her research as a postdoctoral fellow at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) under the guidance of Thales de Freitas, from the same institution, and Eduardo Eizirik, from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS).

The current taxonomic classifications are based on limited available data, which are often incomplete or tentative. Oliveira explains that a unique aspect of his approach is what he humorously refers to as his “brain algorithm,” which, he claims, is better trained than image recognition software. By considering factors such as the animal’s size, ear shape, tail morphology, spot patterns (rosettes), and overall appearance, Oliveira is able to distinguish between different oncilla types at a glance.

A key moment in Oliveira’s oncilla research came in 2011 when American ecologist Rebecca Zug, then a PhD candidate studying the Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus), shared hundreds of photos of felines captured by her camera traps. “I spent the night poring over the images and realized that they weren’t the same species I was familiar with,” recalls Oliveira. Zug, currently affiliated with the University of San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador, is a coauthor of the Scientific Reports article.

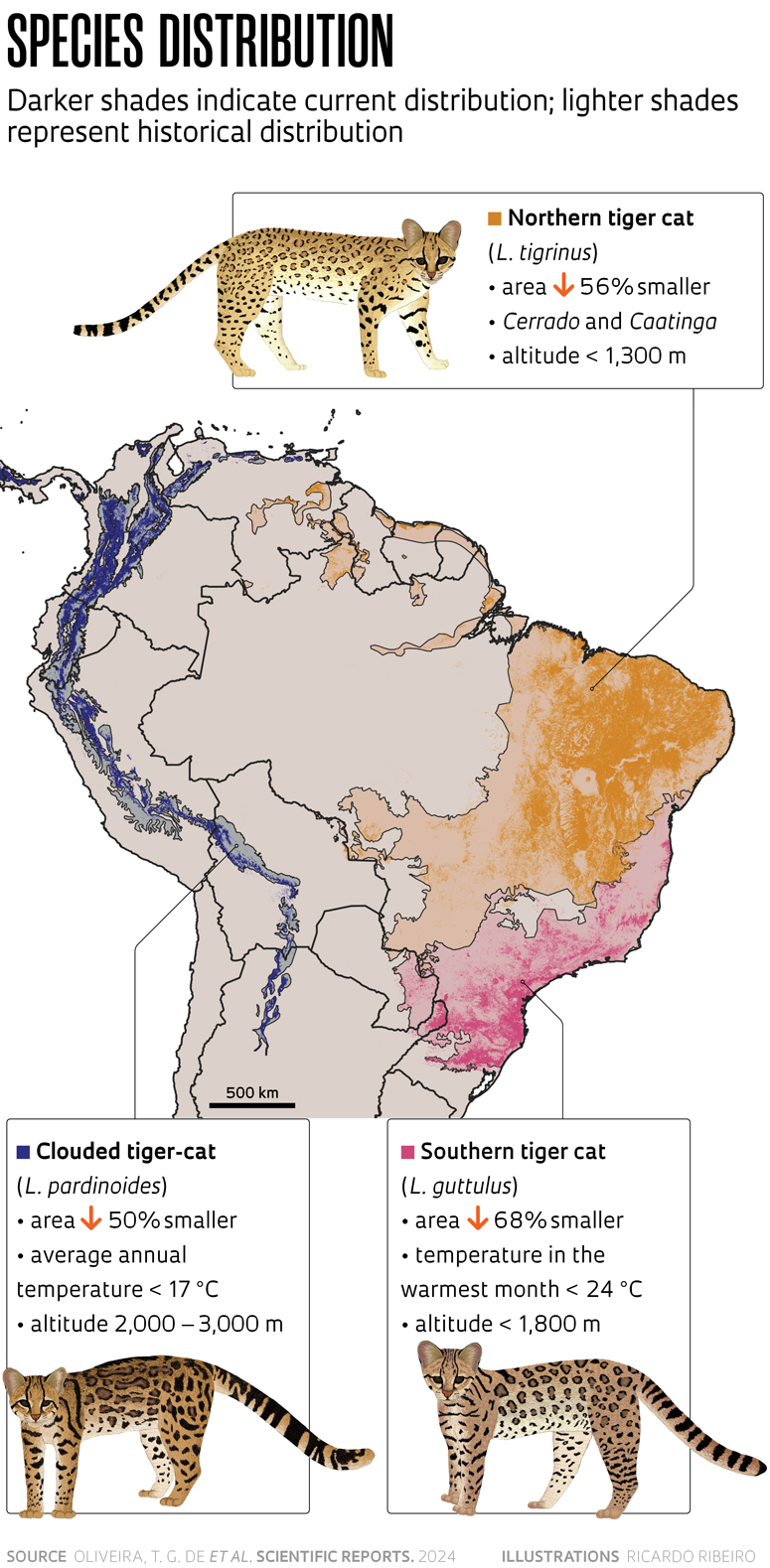

Subsequent research led to a taxonomic reorganization of the L. tigrinus complex and the recognition of a separate species. Andean populations, previously classified as L. t. pardinoides, were found to be markedly distinct from their counterparts—even having two teats whereas other tigrinus subspecies have four. Living in the mist-shrouded forests of the Andes, hence their common name, “clouded tiger cats,” these populations have been redesignated as L. pardinoides.

Adding to the findings from live animal studies is a wealth of genomic data produced by Jonas Lescroart, a Belgian geneticist pursuing a joint PhD between PUC-RS and the University of Antwerp under the guidance of respectively Eizirik and evolutionary biologist Hannes Svardal. In a December article in Molecular Biology and Evolution, he showed that L. pardinoides is closely related to the Central American oncilla. “Genomic, morphological, and ecological data all tell the same story,” says Lescroart. “From a genetic perspective, there’s no doubt that the Andean oncilla constitutes a distinct species.”

“Biogeographic data could shed light on the evolutionary history of these felines, as their current distribution offers a credible narrative of how the different species radiated across South America from a common ancestor in Central America,” Lescroart adds. According to his research, the southern and northern oncillas diverged from a common ancestor approximately 1.46 million years ago, while the Andean oncilla branched off from this lineage about 2.39 million years ago. The separation between populations of L. pardinoides from Central America and those in the northern Andes is a more recent event, occurring between 61,000 and 453,000 years ago.

Genetically placing the population from the Guiana Shield (a geological formation in the northern Amazon, including Amapá) remains a challenge due to sparse sampling in this region. This sampling gap, as termed by biologist Fabio Nascimento, a researcher at the Museum of Zoology (MZ) at USP, also posed a challenge in his earlier work several years ago. In 2017, Nascimento and biologist Anderson Feijó, then a PhD student at the Federal University of Paraíba, collaborated on a taxonomic review published in the journal Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. “We relied on available material from museum collections, primarily consisting of skins, skulls, and skeletons, to examine morphological variation and the taxonomy of the L. tigrinus complex,” Nascimento says.