On June 10 of this year, at the age of 94, Affonso Brandão Hennel, who had for decades managed the company Sociedade Eletro Mercantil Paulista—better known by its acronym SEMP—passed away. Founded in 1942 in the Barra Funda district of São Paulo, SEMP was the first company in Brazil to assemble a television set, accomplishing this feat in 1951. In 1972, it began manufacturing the first national color television, which was sold under the SEMP-Toshiba brand starting in 1977, following a partnership with the Japanese company that lasted until its dissolution in 2016.

The smart TVs now emerging from factories such as the one currently known as SEMP TCL—following a merger with the Chinese multinational TCL Corporation—represent a history of ongoing technological advancement, flawed predictions, and intensifying competition that began 100 years ago. Using a cardboard box, bicycle headlight lenses, sewing needles, and scissors, Scottish engineer John Logie Baird (1888–1946) assembled a device capable of transmitting a static image—the silhouette of a Maltese cross—from an electromechanical transmitter to a receiver a few meters away in 1924. This marked the first TV broadcast in history.

Internet Archive | Memória da PropagandaThe first television magazine from 1928; a 1960s advertisement for the Invictus television set, one of the first brands manufactured in Brazil; and a 1964 edition of Monitor de Rádio e Televisão, a publication that ran from 1947 to 1982Internet Archive | Memória da Propaganda

Two years later, in the presence of members of the Royal Institution, Baird transmitted a moving human figure from one room of his laboratory in London to another. The small, monochrome image was flickering and fragmented, displayed on a screen measuring just 8 centimeters (cm) by 6 cm. The logo for the new product was ambitious: a globe with an eye at its center, accompanied by the words “The Eye of the World.”

In 1927, Baird transmitted a TV signal over a distance of 653 kilometers, from London to Glasgow. The following year, in 1928, he achieved the first transcontinental television broadcast, from London to New York. That same year, Baird also made the first color broadcast, which was described by the scientific journal Nature on August 18 as follows: “Delphiniums and carnations appeared in their natural colours, and a basket of strawberries showed the red fruit very clearly.” The Nature report also predicted: “[…] we are confident that [TV] will become an integral part of our daily lives. Instead of merely hearing an expert describe the progress of a boat race or a soccer match, the younger generation can expect to watch them on television as well.”

The public’s reception was not as enthusiastic as that of the scientists. A memo dated October 1, 1928, from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the UK’s public broadcaster, noted that Baird’s electromechanical TV, which was then undergoing testing, could only capture very slow movements. Any gesture made at normal speed resulted in a blur. Moreover, the expressions of the audience leaving the show “revealed neither enthusiasm nor interest.” This reaction was certainly understandable given the low image quality: while modern TVs have resolutions with over a thousand lines, Baird’s TV had only 30.

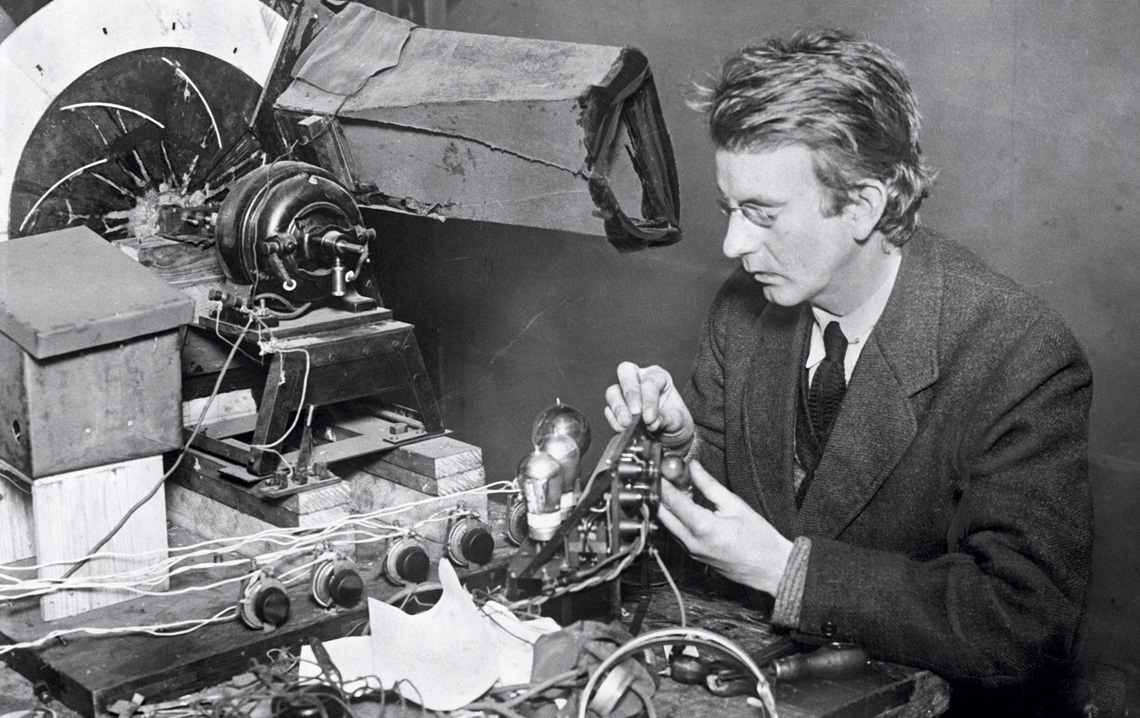

Hulter-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty ImagesIn 1925, Baird adjusts the transmitter of a rudimentary television set he inventedHulter-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Images

Two decades later, despite considerable technical improvements, television still faced some resistance. In 1946, American film producer Darryl Francis Zanuck (1902–1979), founder of 20th Century Fox, was quoted as saying: “Television won’t be able to hold on to any market it captures after the first six months. People will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night.” He couldn’t have been more wrong. After World War II (1939–1945), the economic boom in the United States made TV an affordable and essential consumer product, guaranteeing its prominent place in American living rooms.

Television made its debut in Brazil in 1950, with the pioneering broadcaster TV Tupi in São Paulo, which was inaugurated on September 18 by journalist and businessman Assis Chateaubriand (1892–1968). At that time, there were only 200 TV sets, which Chateaubriand had hastily imported from the United States after realizing there would be no audience to watch the premiere, as noted by writer Fernando Morais in his book Chatô: O rei do Brasil (Chatô: The king of Brazil) (Cia. das Letras; 1994). Today, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) estimates that 71.5 million Brazilian households—nearly 80% of the 90.7 million total—are equipped with a television, which can receive signals from 583 broadcasters and 13,692 repeaters.

Synthesis of knowledge

The term “television” began to be used around two decades before the invention was introduced to the world. It is believed to have been coined by Russian scientist Constantin Perskyi (1854–1906), derived from the Greek word tele (far) and the Latin word videre (to see). He first used the term at the French International Congress of Electricity, one of the events at the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris, where he presented a thesis on the possibility of transmitting images over a distance based on the photoelectric properties of selenium (the ability to convert light into electricity). These properties were demonstrated 27 years earlier by English electrical engineer Willoughby Smith (1828–1891).

Science MuseumThe Televisor, designed by Baird, the first TV receiver sold in Europe in the 1930sScience Museum

“The TV is the result of knowledge and research in various fields, such as mechanics, electricity, and engineering, and was born from the efforts of hundreds of people,” says electrical engineer Marcelo Zuffo, from the University of São Paulo’s Polytechnic School (POLI-USP) and coordinator of USP’s Interdisciplinary Center for Interactive Technologies (CITI-USP). Two major scientific breakthroughs were crucial to this development: the Nipkow disk and, most importantly, the cathode-ray tube.

The invention of German scientist Paul Nipkow (1860–1940) was the key component of Baird’s electromechanical apparatus. The rotating disk with holes that captured images was based on a property of the human eye known as visual persistence. “The image captured by the eye remains on the retina for microseconds,” explains Zuffo. “When the disk was spun rapidly, the images appeared to move.” It was through using Nipkow’s disk that Baird built his pioneering television set.

The rotating disks of the electromechanical TV were soon replaced by analog electronic TV technology, which utilized the cathode-ray tube, invented in 1897 by German physicist Karl Ferdinand Braun (1850–1918). The cathode-ray tube, shaped like a reclining wine decanter, converted electrical signals into images.

Visions4netjournalA 1953 advertisement for a cathode-ray tubeVisions4netjournal

Tube TVs—referred to by researchers as TV 1.0—dominated the global market for decades. Another breakthrough came with the development of color TV in the 1960s, which arrived in Brazil in the following decade.

The next technological leap, TV 2.0, marked the transition from analog to digital systems, which convert signals into binary numbers. The first studies for implementing digital TV in Brazil began the same year it was launched in the United States, in 1998. “We started comparing the digital TV standards from North America, Europe, and Japan,” recalls electrical engineer Cristiano Akamine, from Mackenzie Presbyterian University.

In 2004, Mackenzie hosted the first meeting to formalize a large scientific cooperation network aimed at shaping the Brazilian Digital TV System (SBTVD), a project that mobilized 1,200 Brazilian researchers (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 120). “On June 29, 2006, the federal government published Decree No. 5,820, establishing the Brazilian Digital TV System, based on the recommendations of Brazilian academia,” says Akamine with pride.

Digital TV was launched in Brazil in 2007, and analog transmissions were scheduled to end nationwide by the end of 2024. However, in December 2023, the Ministry of Communications extended the deadline to June 2025. Meanwhile, researchers at the Brazilian Digital Terrestrial TV System Forum are already exploring innovations for digital TV. The so-called TV 3.0 (commercially known as DTV+) promises superior video and audio quality, along with new features such as content personalization, even on free-to-air TV. “TV channel numbers will be replaced by applications from free-to-air broadcasters. Viewers will navigate as if they were using a streaming platform. Television will become more and more like a smartphone,” predicts Akamine. The introduction of smart TVs in 2011 marked a new era. Unlike digital TVs, smart TVs have internet access and applications.

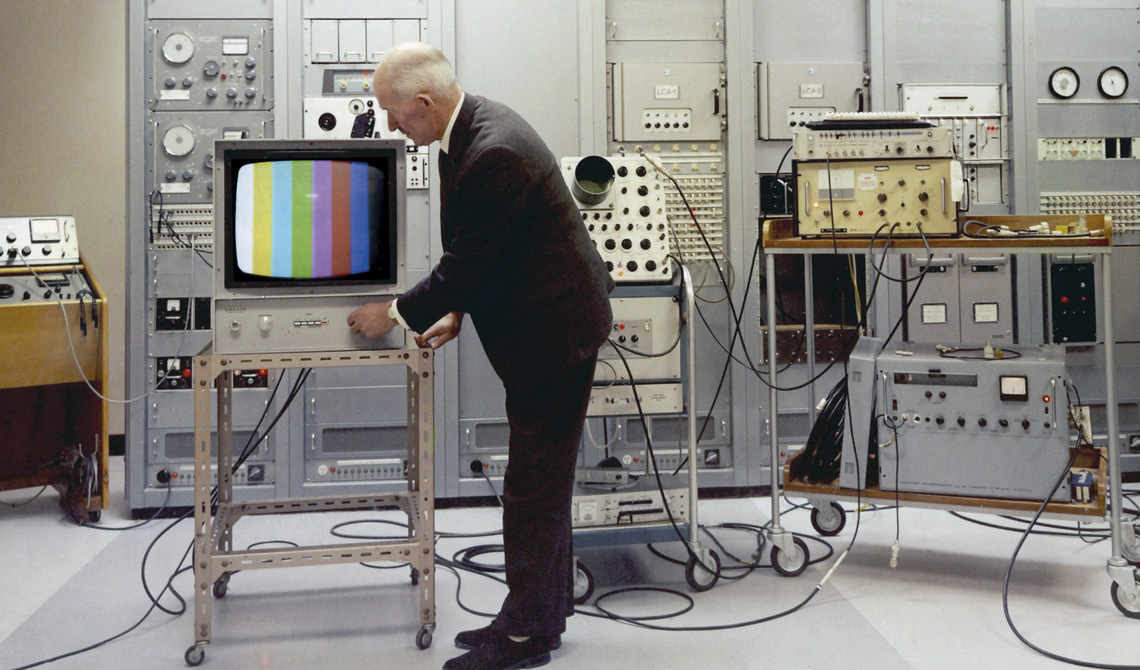

Archives New ZealandColor television test at the Mount Kaukau transmission station, New Zealand, in 1970Archives New Zealand

Space for discussion

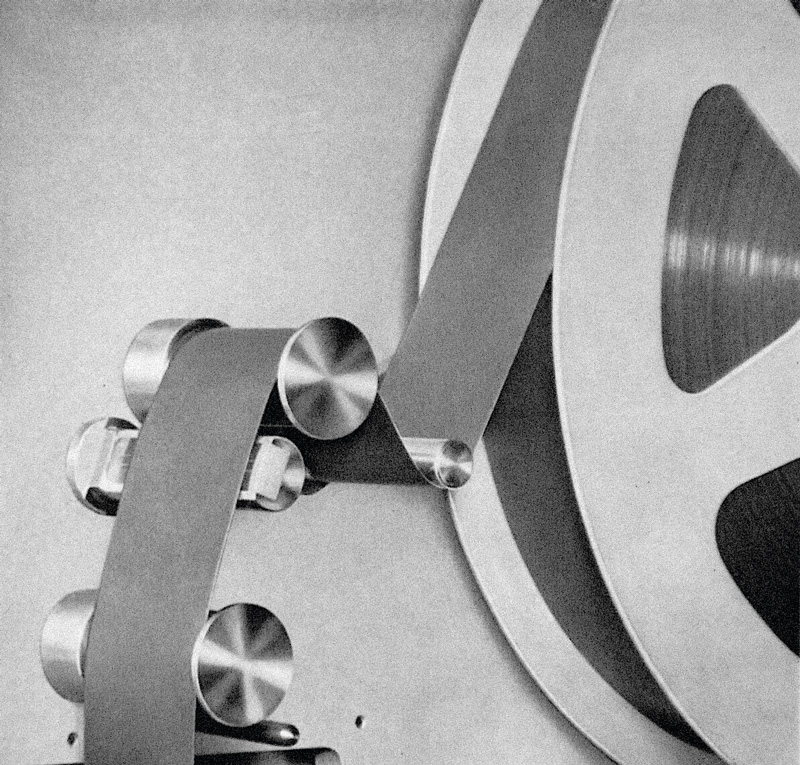

Technological innovations have been accompanied by changes in how television is produced and consumed. One of the first major shifts came with the introduction of videotapes (VT), invented in the United States in 1956 and adopted in Brazil in 1959. While the earliest TV programs were adaptations of popular radio shows and theater performances, which had to be presented live, the advent of videotapes allowed for recording outside the studios, leading to new narrative possibilities in television fiction.

“The ability to record external scenes enabled scriptwriters to bring in locations and references that viewers could recognize,” says social scientist Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes, from the University of São Paulo’s School of Communications and Arts (ECA-USP) and coordinator of the Center for Telenovela Studies (CETVN).

Quad Videotape GroupA clip from the videotape, which allowed the operator to edit parts of the filmsQuad Videotape Group

From 1965 onwards, satellite transmissions further solidified television as the country’s primary means of mass communication. “TV became one of the major agents of cultural and political transformation in Brazil. It reached all social classes, mobilized debates, and even influenced the timing of major sporting and cultural events due to its programming schedule,” explains Gilberto Alexandre Sobrinho, from the Institute of Arts at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP).

According to historian Eduardo Victorio Morettin, also from ECA-USP, television is a privileged historical resource. Supported by FAPESP, he is cataloguing TV Tupi’s journalistic archive, housed at the Cinemateca Brasileira. “We are surveying TV news reports that are relevant for digitization. In one year, we’ve already collected 4,000 news items.”

This catalogued collection will shed light on how TV depicted key historical events such as the amnesty movement, the 1964 coup, student protests, and the May 1968 movement in France. “Our goal is to show how these news programs helped construct a more conservative society,” says Morettin.

Television—and telenovelas in particular—has become a public space for discussing issues that resonate with society. “Television is a communicative tool that, if used effectively, can contribute to social inclusion, environmental responsibility, and respect for diversity,” argues Lopes.

Brazilian Radio and Television MuseumFuzarca and Torresmo, comedians from the 1950s on TV TupiBrazilian Radio and Television Museum

However, the relevance of television in Brazilian society has been challenged in recent years by the rise of the internet and video streaming platforms. Free-to-air TV programs now compete with content produced globally, and television itself faces competition from mobile devices. According to the IBGE’s 2022 Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), 91.5% of Brazilian households now have internet access, and 43.4% (31.1 million) have a paid video streaming subscription. “In several countries, such as the United States, streaming now surpasses broadcast TV in viewership. It’s only a matter of time before this happens in Brazil,” says Sobrinho.

“A new technology doesn’t necessarily replace the previous one,” disagrees Lopes. According to her, a process of mutual influence is occurring in television fiction, with “the serialization of the soap opera and the novelization of the series.” While telenovelas are adopting more dynamic narrative structures, there are already series where episodes are released one by one, as in the soap opera format.

“In Brazil, while the audience is shrinking, free-to-air TV still dominates. It remains one of the only communication platforms that can address a population of over 200 million people,” says communications researcher Melina Meimaridis, who is completing a postdoctoral fellowship at Fluminense Federal University. She predicts that traditional television in the living room will coexist with cell phones and computer monitors. “It’s not one versus the other; the viewer won’t be limited to a single experience.”

The story above was published with the title “Tubes, videotapes, and smart TV” in issue 346 of December/2024.

Project

Audiovisual, history and preservation: The place of Brazilian newsreels and television reports in the construction of memory (1946–1974) (nº 22/06032-0); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Eduardo Victorio Morettin (USP); Investment R$1,767,131.92.

Scientific articles

LOPES, M. I. V. de. Telenovela como recurso comunicativo. Matrizes. Vol. 3, no. 1. Dec. 15, 2011.

MEIMARIDIS, M. Revendo a hegemonia da TV brasileira: O streaming de vídeo como força disruptiva na indústria televisiva nacional. Revista Geminis. Vol. 14, no. 2. Oct. 19, 2023.

VERRUMO, M. A. et al. Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes e os 30 anos do Centro de Estudos de Telenovela da USP: Uma jornada narrada pela teleficção. Matrizes. Vol. 17, no. 1. Apr. 30, 2023.

Books

MORAIS, F. Chatô, o rei do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016.

GOMES, G. O. & LOPES, M. I. (Eds.). Anuário Obitel 2020. O melodrama em tempos de streaming. Porto Alegre: Editora Sulina, 2020.