University of Arkansas

The researcher is launching a book on the eclipseUniversity of ArkansasIn the early 2000s, Irish astrophysicist and science historian Daniel Kennefick, now at the University of Arkansas, joined the team at the Einstein Papers Project, an extensive endeavor that began in 1986 and that is still underway today. Coordinated by researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the Project concerns the publication, with commentary, of thousands of scientific and nonscientific writings, such as letters and other documents, written by Albert Einstein (1879–1955). Kennefick joined the project during the editing of the volume for 1919, the year of the total solar eclipse that provided the first experimental proof that the general theory of relativity was correct. Upon seeing the documents from the era, he noticed that from time to time an author would make a claim that Kennefick had heard before but had not paid much attention to: namely, that British astronomer Arthur Eddington (1882–1944), who coordinated one of the two British expeditions that observed the 1919 eclipse (on the African island of Príncipe), had been a great supporter of Einstein’s ideas and would have therefore deliberately favored the interpretation that the light of stars curves according to the calculations predicted by the theory of relativity and not as Newton’s theory of gravity predicted.

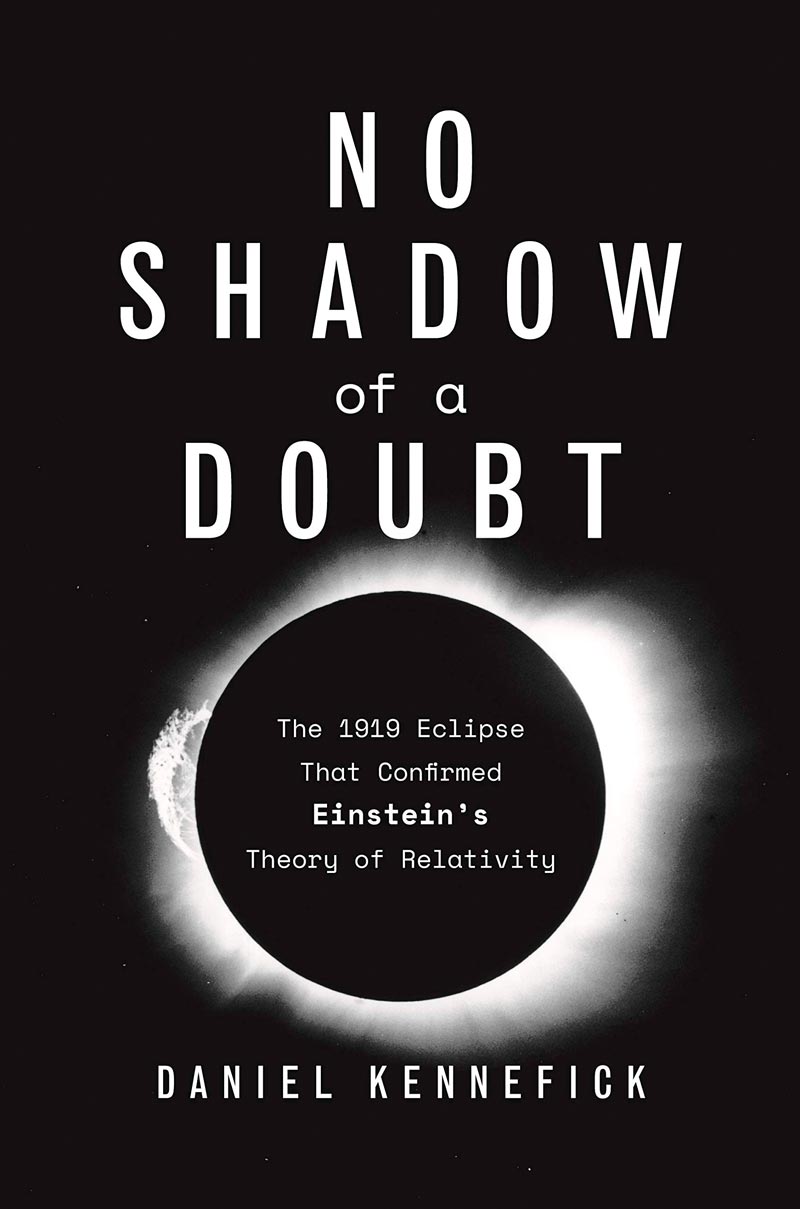

Kennefick became interested in this question and, along with his work as a theoretical physicist in the area of gravitational waves, decided to investigate it in depth. In recent years, he has visited British archives to consult the writings and letters of the time. The result of this work is the book No Shadow of a Doubt: The 1919 Eclipse That Confirmed Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, which will be released in English by Princeton University Press at the end of April. In this interview, the astrophysicist relates the details of the two expeditions, refutes the thesis that Eddington was biased towards Einstein, and points out that without the Sobral data, the 1919 eclipse would not have been useful in confirming the predictions of general relativity.

Why does Eddington’s work analyzing the 1919 eclipse data still generate some controversy, especially in academic circles?

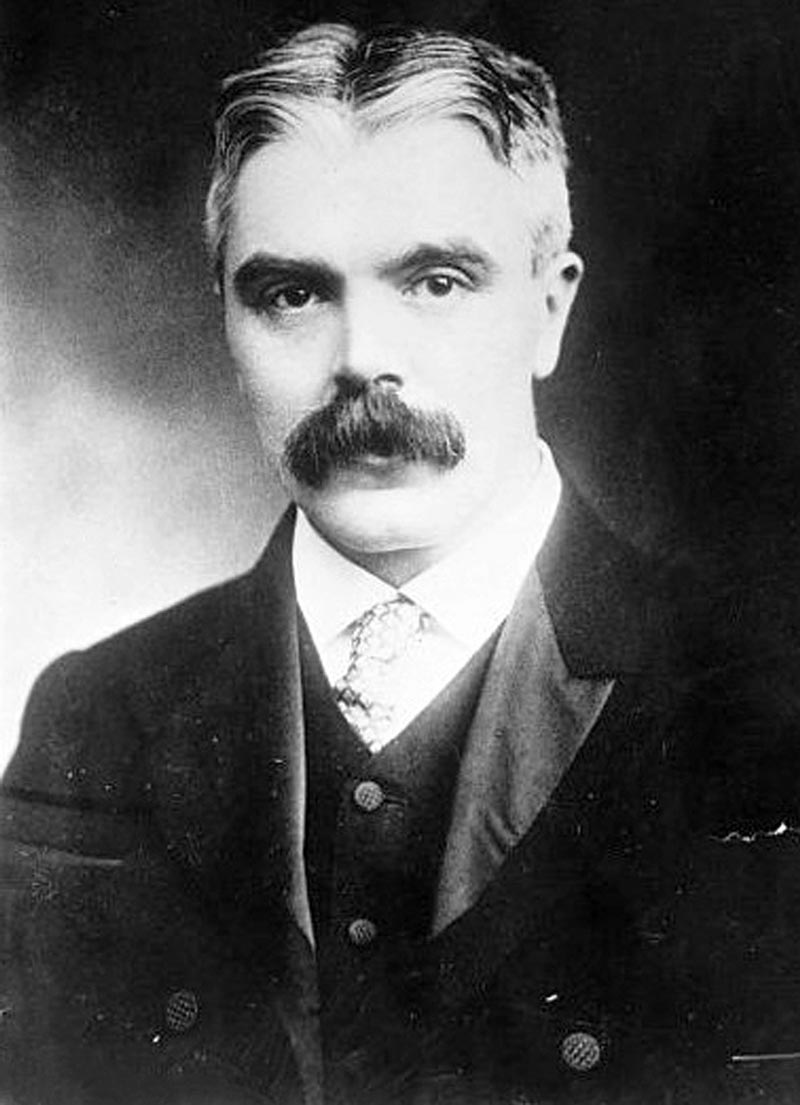

Eddington was a supporter of the theory of relativity in the United Kingdom and eventually became the most famous scientist associated with the 1919 eclipse observations. Some astrophysicists and historians imply that he would have deliberately favored Einstein’s ideas when analyzing the eclipse data. Fortunately, this kind of allegation didn’t gain much traction among nonspecialist audiences. However, one can read comments on the Amazon website from lay readers regarding various works that reiterate this type of criticism of Eddington. Moreover, the role of Frank Dyson [1868–1939], who was the Royal Astronomer of the United Kingdom and the main organizer of the expeditions, has been unfairly neglected. Eddington wasn’t involved in any way with the Sobral data. In addition to not having been in Brazil and therefore not having participated in the production of these records, he didn’t analyze the data from this expedition. This was handled by people from the Greenwich Observatory, basically Dyson, who was the director, and his subordinates.

Is it correct to say that the two British expeditions, one to Sobral and the other to Príncipe, acted independently, although they were coordinated?

Yes. Dyson and Eddington got along well and had a friendly relationship. For a time, before 1919, Dyson was Eddington’s boss when he worked at the Greenwich Observatory. Both knew the importance of the 1919 eclipse. They organized the studies, but the expeditions acted separately. In 1919, each of them was the director of an English observatory: Dyson was at Greenwich, and Eddington directed the observatory at the University of Cambridge. They were in positions that allowed them to mount their own expeditions. Dyson didn’t travel with his expedition to Sobral; he sent two assistants. Eddington took part in the expedition to Príncipe. Because his assistants had died in World War I, he also took a watchmaker who had worked on the instruments in the lab.

Subsequent expeditions were unable to improve on the 1919 measurements in any significant way

Why didn’t Dyson take part in any of the expeditions?

He never said why he didn’t participate, but there are two likely explanations. The most likely reason is that there was a very important meeting in the summer of 1919 that founded the International Astronomical Union, which to this day is the leading international organization of astronomers. He attended the meeting and became one of the principal leaders in the field. Dyson wanted to be at this meeting. In addition, there were few people at the Greenwich Observatory from 1914 to 1918 because of the war, and he didn’t think that he could go away. It was probably a combination of both.

Are the reasons given for discarding the data from the larger telescope used in Sobral reasonable?

I think so. It’s not true that they only discarded the data from that telescope after having obtained a result for the deflection of the light that didn’t match up with Einstein’s theory. I consulted Davidson’s notes, who was Dyson’s assistant in Sobral. They were written a day or two after the eclipse. Davidson said that they had examined the plates from the larger telescope and that they looked horrible, that they couldn’t extract much data from them. Right away, they knew something had gone wrong with the observations with that instrument. They were disappointed, and this problem served as the basis for their later decision to discard these measurements.

Luiz Queiroz

An aerial view of the Eclipse Museum in Sobral, inaugurated in May 1999 and closed since 2014Luiz QueirozAnd the data obtained on Príncipe? How much weight did they have in the final verdict?

Those data were used but weren’t considered good. In this case, the problem wasn’t due to a malfunctioning telescope but due to the presence of clouds at the time of the eclipse. They wouldn’t have been able to make any confirmations with a serious impact if they had needed to rely solely on the Príncipe data. Without Sobral, they wouldn’t have been able to reach a conclusion.

Can the fact that Eddington went to Príncipe, rather than Sobral, be interpreted as an indication that the African expedition was seen as more important than the expedition to Sobral?

The British were afraid of bad weather. Therefore, they planned on going to two places to minimize that risk. That way they would increase the project’s chances of success. I think that’s basically what led them to choose two locations. They probably would have come to Brazil anyway. They had trouble finding a place to observe the eclipse in Africa. The greater part of the continent where the eclipse would be visible was in the jungles of the Congo and inaccessible to them. In 1912, Eddington observed an eclipse in Brazil. Sobral was one of the few places in the eclipse’s path that had a relatively dry climate, which increased the chances of experiencing good weather there.

Smithsonian Institution

Eddington…Smithsonian InstitutionWhy did the data from the 1919 eclipse take years to be fully accepted by scientists?

I wouldn’t say that other scientists—especially astronomers—didn’t believe the data; I believe they thought that the measurements needed to be confirmed by other studies. This is typical behavior in science, which mustn’t simply accept someone’s word about something. Under normal circumstances, scientists immediately try to replicate a result that is so important. However, in the case of Einstein’s theory, we had to wait for the occurrence of another eclipse to try to do that. This particularity made that situation special. It was necessary to wait for years to try to make new measurements. This added a certain drama to the situation. Although they confirmed the data from Dyson and Eddington, subsequent expeditions failed to significantly improve the accuracy of the measurements.

Einstein really didn’t interfere in Dyson and Eddington’s final conclusions?

He didn’t communicate with any of the English astronomers, not even Eddington, whom he later came to know reasonably well. Through the media, Einstein knew that the British scientists had gone on an expedition to try to prove his theory. Einstein wasn’t an astronomer and was never involved in this kind of a measurement. However, he encouraged people to take on this kind of an enterprise and even helped raise money for a German expedition before 1919.

US Library of Congress

…and Dyson, the British coordinators of the expeditions to Príncipe and SobralUS Library of CongressWhat did you see as interesting in the archives from the British expeditions?

I’ve read the letters that Eddington sent to his mother’s house and notes from the committee meetings that organized the expeditions. However, what was most important was obtaining access to the data analysis produced by the Dyson team. They kept records of the data and of their calculations. Thus, I was able to see how they did the analyses and came to their important conclusion of rejecting the data from the larger telescope used in Sobral.

Was this kind of data unavailable from Eddington’s expedition to Príncipe?

Unfortunately, for some reason I’m unaware of, no data from this expedition has survived. The photographic plates were lost. I’ve talked to many archivists and no one knows what happened. The loss must have occurred more than 50 years ago. The plates from Sobral survived and were used in a reanalysis of the eclipse data, which was done by other researchers in 1979. However, I’ve never seen them. I talked to some astronomers about this. They say that after 1979, the Sobral plates were moved and no one could tell me exactly where they are. They must be mixed in among other plates.