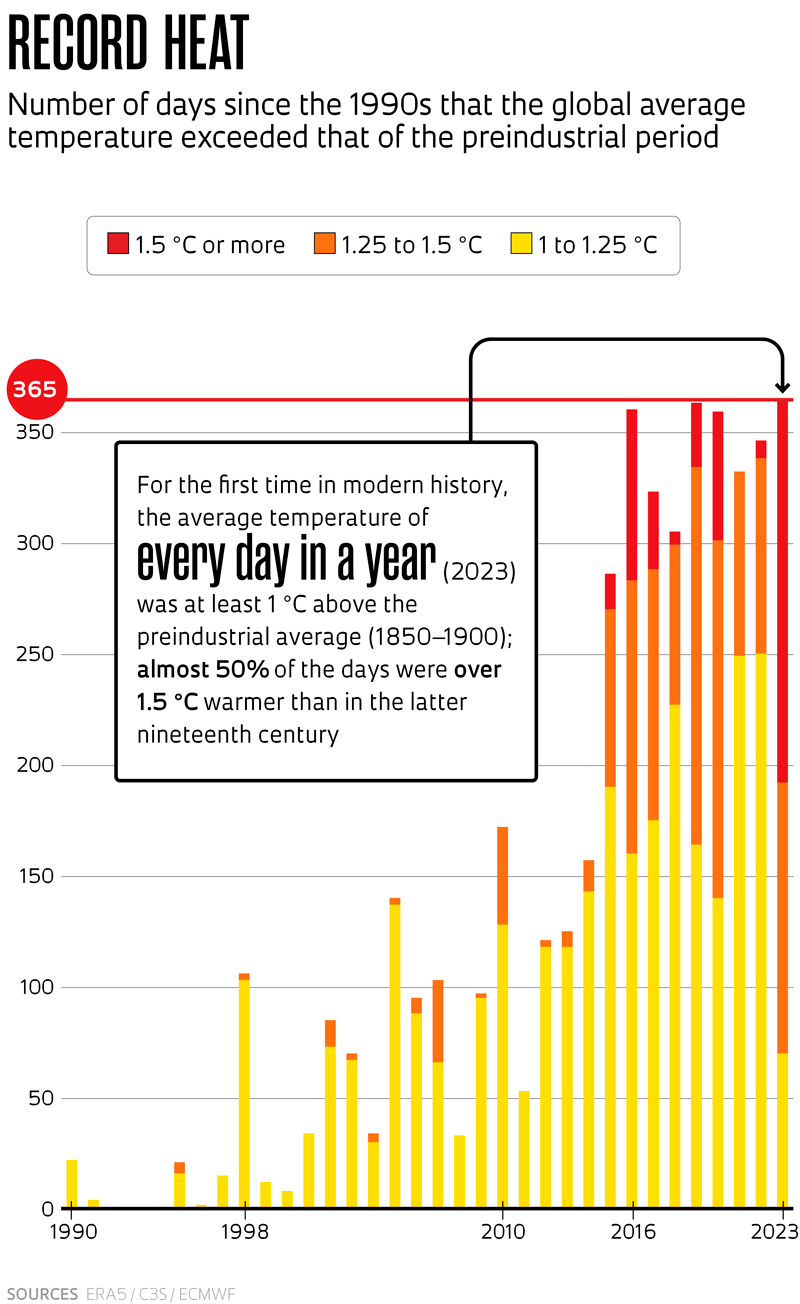

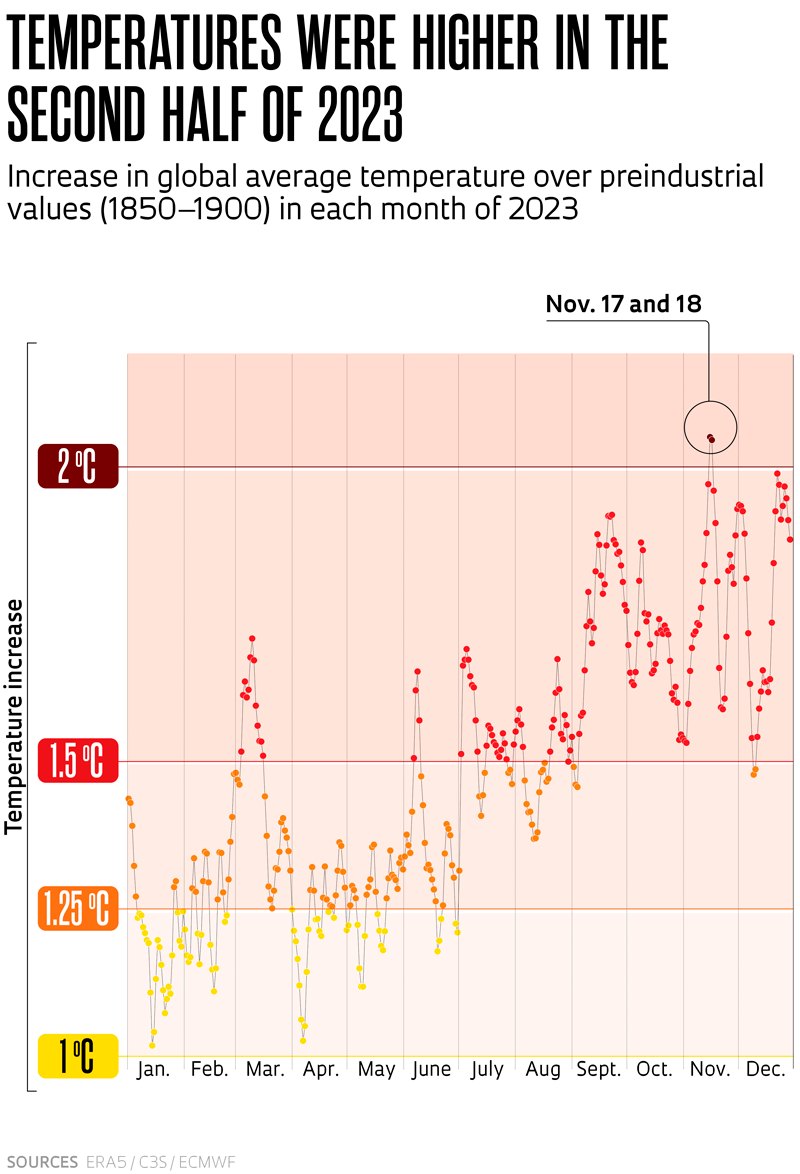

The figures that follow are unparalleled in modern human history. All 365 days of 2023 were at least 1 degree Celsius (ºC) warmer than the global average temperature between 1850 and 1900. Almost half of them were 1.5 °C or more above this baseline, which represents the climate of the preindustrial era. On two days — November 17 and 18 — temperatures more than 2 °C above the late nineteenth century average were recorded for the first time (see graph).

These data, released at the beginning of January by the European climate change service Copernicus, confirm the predictions that 2023 was the hottest year on the planet since 1850. The average temperature of Earth’s atmosphere hit 14.98 °C, which is 0.17 °C above the previous record, set in 2016, and 0.6 °C above the average for the period 1991–2020. It was 1.48 °C warmer than the average for the period 1850–1900.

Using data from Copernicus and five other international services that monitor the global average temperature, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) also confirmed that 2023 was the hottest year since records began in 1850. According to the WMO survey, last year’s temperature was 1.45 °C higher than the preindustrial average, almost equal to the value calculated independently by the European agency. The WMO’s margin of error is 0.12 °C.

“Climate change is the biggest challenge that humanity faces. It is affecting all of us, especially the most vulnerable,” said Argentine meteorologist Celeste Saulo, the WMO’s first female secretary-general, in a press release. “We cannot afford to wait any longer. We are already taking action, but we have to do more and we have to do it quickly. We have to make drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and accelerate the transition to renewable energy sources.”

The latter half of last year was especially torrid. Every month between June and December 2023 was the hottest in modern history compared to the same month in each of the last 172 years, according to Copernicus. Most of the days that averaged 1.5 ºC above preindustrial temperatures last year occurred during this period (see graph).

The annual average atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) — the two greenhouse gases that contribute most to global warming — continued to rise in 2023, remaining at the highest value ever recorded. The CO2 concentration was measured at 419 parts per million (ppm) and CH4 at 1,902 parts per billion (ppb).

“The extremes we have observed over the last few months provide a dramatic testimony of how far we now are from the climate in which our civilization developed. This has profound consequences for the Paris Agreement and all human endeavors,” said Italian physicist Carlo Buontempo, director of Copernicus, in a press release. “If we want to successfully manage our climate risk portfolio, we need to urgently decarbonize our economy whilst using climate data and knowledge to prepare for the future.”

Ratified at the end of 2015, the Paris Climate Agreement is an international treaty signed by almost 200 countries with the aim of limiting global warming this century to a maximum of 2 °C above the average preindustrial temperature. Ideally, the increase would be limited to 1.5 °C, which would still be considered high and would lead to a serious climate crisis, but for which the socioeconomic losses would, in theory, still be manageable.

According to data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC), Earth’s climate is currently almost 1.2 °C warmer than it was in the mid-nineteenth century. As indicated by the most recent global data, the 1.5 °C global warming threshold was equaled and exceeded for much of last year. “I remember discussing at IPCC meetings that this limit would be reached within a few decades, but we are seeing it happening right now,” says Pedro Leite da Silva Dias, a meteorologist from the Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of São Paulo (IAG-USP).

Brazil is no exception when it comes to climate extremes. Last year was the country’s hottest on record since the National Institute of Meteorology (INMET) began keeping records in 1961. The average temperature in 2023 was 24.92 °C, which is 0.03 °C hotter than the previous record, set in 2015, and 0.69 °C higher than the average for the period 1991–2020.

“Everything indicated that 2023 was warmer than normal. We faced nine heat waves over the year,” points out INMET meteorologist Danielle Ferreira. “We had a very atypical winter with few air mass inflows, and a spring in which the rainfall came late in central Brazil. In December, at the beginning of the summer, there was also little rain.”

The institute’s historical data indicate that the country is becoming warmer decade on decade. Four of Brazil’s five hottest years occurred recently: in 2023, 2015, 2019, and 2016, in decreasing order of average temperature. Only the fifth was recorded in the previous century, in 1998.

There is a general consensus that in addition to global climate change, the natural phenomenon of El Niño has had a significant part to play in the heat records set since last year. The weather event is characterized by unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. A moderate-strong El Niño has been occurring in this oceanic region since mid-2023, affecting temperatures and rainfall patterns in various areas of the world.

Republish