The framework for benchmarking graduate programs in Brazil will see its most extensive overhaul in more than two decades. The Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), a Ministry of Education agency responsible for assessing the quality of master’s and doctoral programs, has announced that the country’s more than 4,000 active programs will no longer be benchmarked using a single composite score—currently on a scale of 3 to 7 for recommended and recognized programs—but will now be assessed across five different dimensions: Education and Training, Research, International and Regional Engagement, Innovation, and Societal Impact. The details of the new framework will be fleshed out over the coming months by experts from the academic community and the technical department at CAPES. The changes will be effective for the assessment cycle beginning in 2021, and the results will be reported in 2025.

The goal is to provide more meaningful and comprehensive insight into program quality across different aspects, revealing strengths and weaknesses. CAPES chairman Anderson Ribeiro Correia says the current model, with its focus on research and education metrics, has played an important role in expanding graduate education in Brazil since the 1960s, but has become too narrow to accommodate the growing diversity of programs. “We’ve created high-quality graduate programs that have different strengths. But we’ve continued to measure their quality on the basis of scholarly publishing only,” he says. Correia notes that the system in place gives little weight, for example, to how university training benefits the lives of alumni, or the development of local communities. “There are programs that give a significant boost to students’ careers, supporting better pay and social mobility. Other programs have a notable impact on local economies, even if they are not quite at the state of the art. By recognizing and encouraging these contributions, we can amplify the impact that graduate education has on Brazil’s development.”

The idea of radically changing the current model has been two years in the making. After announcing results for the 2013–2016 assessment cycle, CAPES managers commissioned a study from the institution’s Technical-Scientific Board on aspects of the system that needed improvement. Experts and organizations in the field of graduate education were consulted and offered two key insights: the importance of universities self-assessing their programs—describing their initial expectations and whether they have been met; and the need to implement metrics that reflect the different missions that graduate programs can pursue other than high-quality research, such as supporting regional development and collaborating with industry.

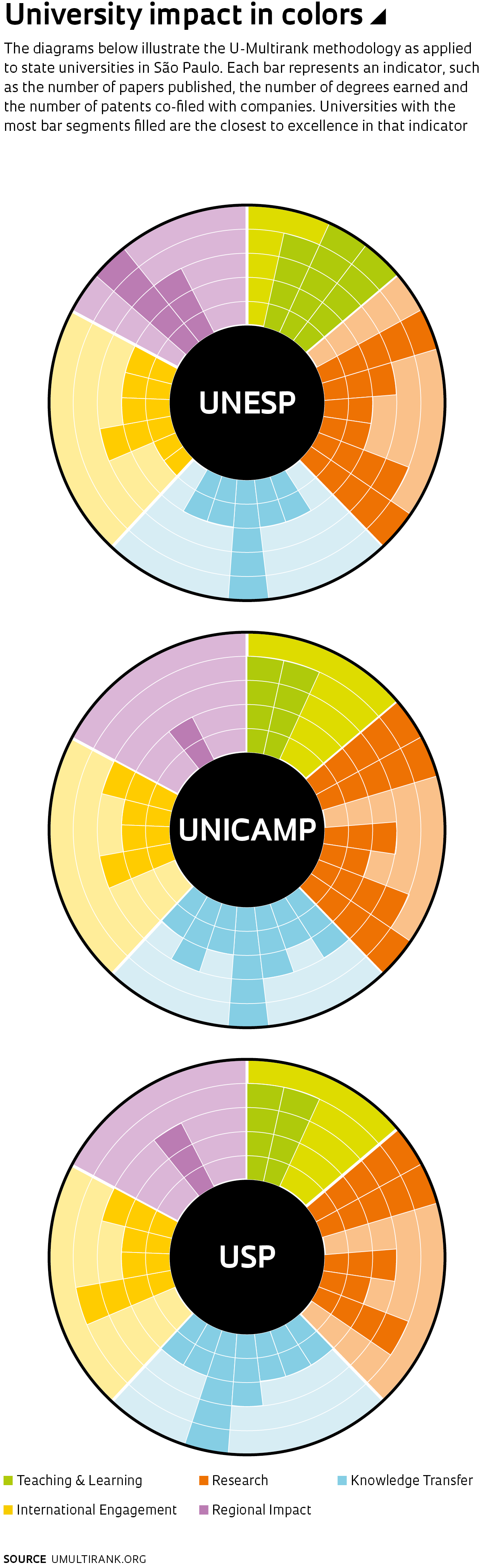

In late 2018, CAPES sent a delegation to Germany and the Netherlands, including SBPC’s honorary chairwoman, Helena Nader, and the agency’s Assessment Director, Sonia Baó, to learn more about U-Multirank, a university benchmarking tool that seemed to align with their aspirations for change in Brazil’s graduate education model. U-Multirank measures universities’ strengths and weaknesses across five different dimensions: teaching and learning, research, knowledge transfer, international orientation, and regional engagement. The results are displayed in a five-color sunburst chart representing the five assessment dimensions, with bars showing the level of performance for each indicator.

The framework was created in 2014 by the Center for Higher Education Development in Gütersloh, Germany, and the Center for Higher Education Policy Studies at Universiteit Twente, the Netherlands, as part of a European Commission initiative to develop an approach that provides a better measure of European universities’ individual strengths than available international rankings. It is currently used by universities in 96 countries, including Brazil, where it has been adopted by the three state universities in São Paulo. Brazil’s new graduate benchmarking model will likely draw inspiration from U-Multirank, but will be adapted to CAPES’ evaluation goals. “U-Multirank was developed to provide a comprehensive assessment of universities and has many indicators that are specifically for undergraduate education. Purpose-appropriate indicators will need to be developed to measure the quality of graduate programs,” says Abílio Baeta Neves, who served as chairman at CAPES between 2016 and 2018, when plans were first made for the new framework.

The changes announced in the CAPES assessment model have been well received by the academic community. Zoologist Telma Berchielli, associate dean for graduate student affairs at São Paulo State University (UNESP), says that an approach that recognizes all the different facets of graduate education has been well overdue. “The previous approach was extremely rigid. It seemed primarily concerned with people being trained to work at universities, whereas today many PhDs go on to work in industry. They contribute to society just the same, but in a different way,” she says. UNESP has a broad offering of programs, she notes—some very well ranked, and others that have yet to reach maturity, but all generating regional impact through the universities’ network of campuses in 24 cities. She cites as examples the animal biology program at the university’s campus in São José do Rio Preto, which is less than 10 years old and yet earned the top score (7) in the most recent edition of the CAPES assessment; and the coastal biodiversity program offered at the campus in the seaside city of São Vicente, which received a more modest score of 4. “But both provide local impact by creating knowledge and training specialists, and this has not been adequately recognized.” Berchielli especially welcomes the introduction of self-assessments in the new model. “This exercise will show what each program’s strengths are, what the university’s mission is, and where its best research is focused.”

Statistician Nancy Lopes Garcia, associate dean for graduate student affairs at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), agrees that the evaluation model needs an overhaul, but has a number of concerns. “Too much focus could be placed on the economic and social impact of a program. How would this dimension apply to basic science programs, which can take years to develop applications, but are essential in making those applications possible? How can one measure the economic and social contribution of a program, for example, in mathematics?” she wonders. She believes UNICAMP will not be significantly affected by the changes, however. “We have consistently invested in the quality of our programs, which for the most part are very solid and internationally competitive. Just under half of our students are in graduate programs, the highest proportion among universities in São Paulo.”

While the impact from the new guidelines is difficult to predict before the details are known, Baeta Neves believes the potential implications could be substantial. “It won’t be a simple matter as it will upset a deeply rooted assessment culture that has influenced the design of current programs. They will have to orient themselves without the composite scoring system they use today, and this is uncharted territory for them,” he explains. The CAPES assessment, which is used as a basis for awarding grants and funding, has shaped the functioning of Brazil’s graduate education system over time. Before 1996, programs were ranked using alphabetical ratings from A to E. In subsequent years, a score of 1 to 5 was assigned to programs offering only master’s degrees, and up to 7 for programs including doctoral degrees. In 1998, differential scores of either 6 or 7 were introduced to reflect aspects such as international engagement and faculty experience abroad. By then, internationalization had come to be recognized as a key lever in research—studies had shown that research in collaboration with foreign institutions had a four times greater citation impact than research done locally.

In the past 20 years, the number of programs has almost tripled and society has become increasingly demanding in terms of the impacts science is expected to produce, but the assessment system has not kept up with the times. Baeta Neves says the future model could be highly transformational if it abandons what he sees as an excess of normative requirements in the current model. “Universities, especially the most prestigious ones, need to be allowed more leeway to experiment. The current system is highly controlling and imposes requirements that are entirely unrelated to excellence. It requires, for example, a minimum number of professors in each program. But why would having 12 faculty be better than having, say, 10 or 9?”

Brazil’s graduate assessment system is globally unique. In the US, program accreditation and assessment is done in a decentralized manner by scientific associations. The most recent countrywide assessment of doctoral programs in the US was carried out in 2010. The report, published by the National Academy of Sciences, examined data for the 2005–2006 academic year from 5,000 programs in 62 fields at 212 institutions. Compared with data from the mid-1990s, the numbers of doctoral students had increased by 4% in engineering and 9% in the physical sciences, but declined by 5% in the social sciences and 12% in the humanities. Interestingly, the report found that doctoral education in the US was dominated by programs in public universities—72% of the doctoral programs in the study were in public universities. Of the 37 universities that produced the most PhDs from 2002–2006, only 12 were private universities.

The Brazilian assessment framework is similar in scale to the system used to monitor research quality at universities in the UK, where assessments are conducted every five years to determine the allocation of research funding for the following period. “UK assessments are on the basis of research only as there are no graduate programs proper to be evaluated as in Brazil. To do doctoral research, students approach potential supervisors with a proposed project. If accepted, their research will count toward a PhD degree,” explains Baeta Neves.

Not only will the CAPES model see radical changes starting in 2021, but the current assessment process (for the period 2017–2020) has also been reformulated so that it values the quality of research over quantity. The assessment form now has three items instead of five, and different weights. For example, it now recognizes the scientific output of alumni, and not only faculty. “Until the previous edition, indicators related to the student body were more quantitative in nature—such as the number of students enrolled and the average time taken to earn degrees. The assessment now measures students’ scholarly output within five years of completing their master’s or doctoral degrees. While citations will only be captured in the short term, this is progress nonetheless,” says Nancy Garcia of UNICAMP.

Qualis, the system CAPES uses to benchmark the quality of research produced by graduate programs, is also being reformulated. Science journals are rated on their impact and prestige in their respective fields, and programs that publish in the most prestigious journals score additional points in the assessment. The goal in the reformulation is to make the Qualis system less subjective. Whereas previously a journal could be rated high in one field but low in another, in the following assessment cycle a single rating will be used across all fields. But each field will be permitted to partly adjust the rating, either up or down two levels for 10% of journals, or up or down one level for 20% of journals.

The most significant change relates to the quality of research. Rather than reporting the number of papers at the highest tiers of the Qualis assessment, programs will now submit a selection of what they believe to be their highest-quality papers and documents for review. Information scientist Rogério Mugnaini, of the School of Communications and Arts at the University of São Paulo (USP), says that valuing the quality of research over quantity can have a beneficial effect. “In the CAPES assessment, there are some fields that place too much emphasis on quantitative metrics, leading researchers to push to publish as much as they can at any cost, often at the expense of quality. This can also congest the peer review system,” he says. Mugnaini notes that similar reformulations are being implemented internationally. The UK’s assessment system, which previously used more quantitative criteria given the amount of effort it would take to review all university research over a five-year period, has reintroduced criteria based primarily on peer review. “Changes in the CAPES system are often proposed by experts in different fields and do not always reflect recent global developments in science assessment. When considering prospective changes, it is important that current best practice be taken into account.”

Republish