When Leandro Moreira arrived from São Paulo to take up a research position at the Federal University of Ouro Preto (UFOP), the biologist was surprised to find that the environmental protection areas near the campus were teeming with frogs and toads. Moreira found it surprising because of the high concentrations of arsenic, a potent poison known to exist in the soils and water of that region.

Arsenic naturally occurs in the Ouro Preto prefecture of Minas Gerais State and throughout the Quadrilátero Ferrífero (iron quadrangle) region, and mining activities have caused the contamination to worsen over recent decades. Toxic and carcinogenic, arsenic ranks among the most dangerous pollutants for health — together with mercury, lead, and cadmium. A single dose of 125 milligrams can kill an adult human. So how do animals survive when they breathe through a thin layer of skin and require constant contact with water, making them extremely vulnerable to environmental toxicity?

The survival of amphibians in contaminated environments has now been partially explained. The research Moreira coordinated identified arsenic-resistant bacteria on the skin of amphibians in the region. Moreover, the study provided the first experimental evidence that such bacterial resistance extends to the host, providing some amount of protection against poisoning, as detailed in an article published in May in Scientific Reports.

Amphibians (frogs, toads, tree frogs, salamanders, and caecilians, or blind snakes) are known to be sensitive to changes in temperature, solar radiation, and pollutants. “If the natural environment is suddenly disturbed by the release of a substance or a change in climate, they are often the first vertebrates to disappear,” Moreira explains. For this reason, many researchers use amphibians as bioindicators of environmental quality and have nicknamed them the “canaries in the coal mine” of global climate change. The term refers to an old practice in England, where the small birds were taken into mining tunnels to warn of elevated concentrations of lethal gases. If the birds began to faint, it was a sign that the workers should leave.

Adriano Lima SilveiraThe Blacksmith Toad (Boana faber), included in the experiment, is one of the species that resist toxins in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero regionAdriano Lima Silveira

In vertebrates, the skin is the first line of defense against pathogens and toxic substances. Amphibians have permeable skin, meaning that substances from the air and water easily enter their bodies. The skin microbiota, a community of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, and fungi that live and thrive on vertebrate skin, is one of the few barriers protecting the body’s interior from the external environment.

Like gastrointestinal bacteria, whose importance to overall health has been the subject of growing research, skin bacteria work in groups. They recognize each other’s presence and can secrete substances into their environment that facilitate their proliferation and provide protection, forming a layer known as a biofilm. The UFOP researchers had already detected arsenic tolerance among these bacteria in 2019, as they described in an article in Herpetology Notes. However, the microorganisms’ resistance did not necessarily signify that frogs and toads benefited from this bacterial layer. It remained to be proven whether the biofilm formed by the microorganisms conferred the power to block the toxic substance.

Roadside slaughterhouse

Moreira and biologist Isabella Cordeiro, a doctoral student in his lab, needed to select species representatives living both in arsenic-rich and pollution-free environments. Such was the case for five species — four tree frogs and one toad — found both in the Quadrilátero Ferrífero and in a forest reserve in João Neiva, Espírito Santo, where the water does not contain arsenic. The researchers traveled to the reserve in Espírito Santo to collect microorganisms from the amphibians’ skin.

Thanks to the kind of fortuitous encounters that can occur during fieldwork, on one return trip they came across a bullfrog farm that was breeding a North American species (Lithobates catesbeianus) commonly raised for food. The researchers stopped to talk to the frog farmers and discovered that the frogs’ skins were discarded after the meat was harvested. The owner agreed to send the frozen skins to the university.

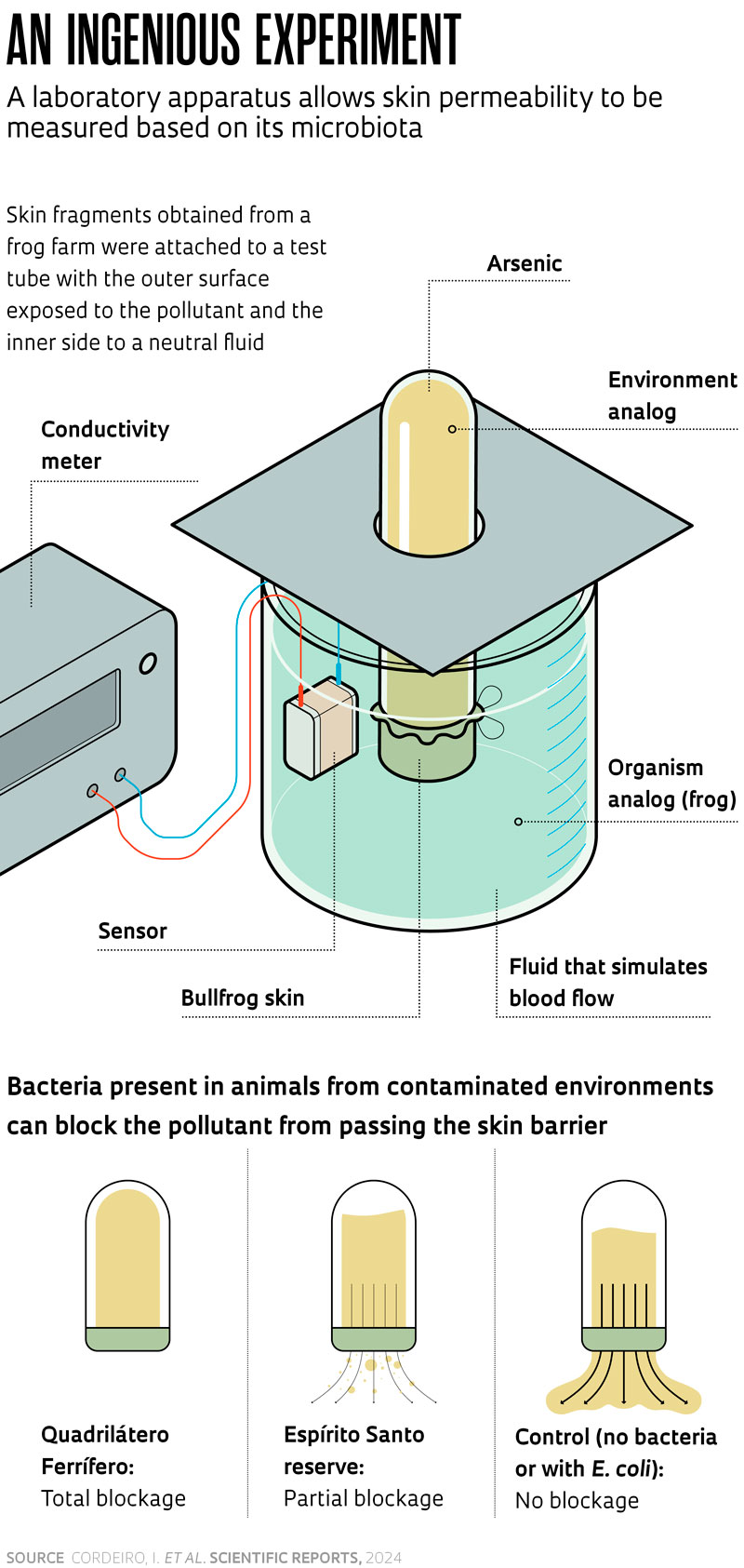

Back in the lab, the researchers sterilized the bullfrog skins and applied four different treatments to their outer surfaces: arsenic-tolerant bacteria from amphibian skin from the Quadrilátero Ferrífero, bacteria from frogs from the uncontaminated area, and two controls—one was left bacteria-free and one applied with only Escherichia coli, which typically does not inhabit skin (see infographic). The results supported the researchers’ protective layer hypothesis: arsenic passage was blocked only in skins coated with bacteria collected from amphibians in the naturally contaminated regions of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero.

The team also observed that the bacteria in the experiment proliferated within the test tube solution, potentially indicating that they have adapted to take advantage of the arsenic environment, deriving energy from processing the element. While studies on the composition and toxin tolerance of bacteria in the amphibian skin microbiota have been conducted in other regions of the world contaminated by heavy metals, pesticides, herbicides, and other pollutants, the authors say no one had previously evaluated the role of bacteria and the permeability of amphibians’ skin to contaminants.

Protective yes, infallible no

“Amphibians remain excellent bioindicators of environmental disturbances, but we must also consider the nature of each threat and whether evolution has had time to respond,” suggests Moreira. In mineral-rich regions where a contaminant was present even before human intervention, prolonged exposure might have allowed microorganisms to adapt.

Thinking about the time evolution requires and about different types of adaptation led Brazilian ecologist Guilherme Becker of Pennsylvania State University (PSU) in the United States to focus his research on amphibians and reptiles from various countries to understand how pathogens affect microbiota and how microorganisms, in turn, affect pathogens. His team also investigates how climate factors influence this interaction.

This effect is especially relevant in the context of a worrying pandemic disease among amphibians, called chytridiomycosis. The fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, also known as chytrid or Bd, is responsible for the extinction of dozens of frog, toad, and tree frog species and has affected hundreds more.

Adriano Lima SilveiraThe pajama tree frog (Hypsiboas polytaenius) lives in vegetation around flooded areas, where it lays its eggsAdriano Lima Silveira

At PSU, the team led by Becker, who is a coauthor of the arsenic tolerance paper, has already discovered that periods of prolonged drought reduce the quality of the skin microbiome’s protection against fungi, as described in an article in January’s Ecology Letters. Invasion by other pathogens, such as viruses or fungi (chytrid or others), can reduce this protection.

Contact can be either harmful or beneficial. “It’s like vaccination: with exposure to small, constant, and continuous concentrations of viruses or fungi over time, the microbiota tends to become more combative, and certain types of bacteria produce antifungal substances because gradual exposure changes the composition of bacterial species inhabiting the frog over time,” explains Becker, who published these findings in 2023 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

Some bacterial types have already been identified as effective against chytrid, such as certain Pseudomonas species, but researchers emphasize that none of them guarantees protection by itself. The key lies in the diversity of species within the microorganism community living and interacting on the skin. When a microbiome (or forest) is diverse, invasion by new organisms becomes more difficult, and the system as a whole tends to be more stable.

If diversity is disrupted, stability is also compromised, making the system vulnerable and facilitating the entry of “enemies.” Becker’s studies indicate that in addition to pathogens and drought events, other factors, such as forest cover and direct solar radiation can destabilize diversity on multiple scales — from microbiota to large ecosystems.

In tests with amphibians from Brazil and Madagascar described in 2022 in the journal Animal Microbiome, Becker found that species threatened by extinction due to chytrid have much less diverse microbiota than those not under threat. Another analysis conducted in partnership with herpetologist Jackson Preuss from the University of West Santa Catarina (UNOESC), discovered that lakes with high concentrations of fecal coliforms also impair microbiota species composition, according to a 2020 article in Environmental Science and Technology.

Adriano Lima SilveiraThe small cururu toad (Rhinella crucifer) lives further away from water, and has less-resistant microbiotaAdriano Lima Silveira

The researchers observed that the microbiota diversity of Dendropsophus minutus tree frogs decreases in ponds where carp farmers normally dump pig feces, compared to waters not affected by this practice, which is common in southern Brazil. In frogs from contaminated ponds, the bacterial species that died left room for colonization by others that facilitated the entry of the fungi that cause chytridiomycosis. “This shows that a disruption in equilibrium can have various origins; a healthy microbiota needs to be diverse to respond to mycoses and viruses,” Preuss observes.

The antifungal role of skin microbiota has garnered more attention due to the interest in finding solutions and developing probiotic treatments for chytridiomycosis, notes Mexican microbiologist Eria Caudillo from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), who considers it essential to broaden the scope of research to the microbiota’s other functions, as the UFOP study did. “Chytridiomycosis affects about 8% of the world’s amphibian biodiversity, but other factors like deforestation, invasive species, and environmental contamination are more pervasive.”

Caudillo, who works with the critically endangered axolotl salamander, highlights other difficulties reported by Brazilian researchers, including the limited number of studies that have been conducted with live amphibians due to challenges in obtaining environmental permits and the need for resources and infrastructure. “That’s the beauty of the experiment done with arsenic-tolerant amphibians; the apparatus they invented was innovative, low-cost, and didn’t unnecessarily kill animals.” She emphasizes other potential applications of this knowledge, such as developing biological filters using pollutant-resistant bacteria.

The rapid life cycle of bacteria enables them to respond to evolutionary pressures much faster than animals. This could make them the best fighters against environmental changes caused by human activity. However, they are not invincible. When significant, sudden impacts occur, no amount of diversity or defensive shields can withstand them.

Scientific articles

CORDEIRO, I. F. et al. Amphibian tolerance to arsenic: Microbiome-mediated insights. Scientific Reports. vol. 14, 10193. may 3, 2024.

CORDEIRO, I. F. et al. Arsenic resistance in cultured cutaneous microbiota is associated with anuran lifestyles in the Iron Quadrangle, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Herpetology Notes. vol. 12. oct. 30, 2019.

GREENSPAN, S. E. et al. Low microbiome diversity in threatened amphibians from two biodiversity hotspots. Animal Microbiome. vol. 4, 69. dec. 29, 2022.

PREUSS, J. F. et al. Widespread pig farming practice linked to shifts in skin microbiomes and disease in pond-breeding amphibians. Environmental Science and Technology. vol. 54, no. 18, pp. 11301–12. aug. 26, 2020.

BUTTIMER, S. et al. Skin microbiome disturbance linked to drought-associated amphibian disease. Ecology Letters. vol. 27, no. 1, e14372. jan. 26, 2024.

SIOMKO, S. A. Selection of an anti-pathogen skin microbiome following prophylaxis treatment in an amphibian model system. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. vol. 378, no. 1882. july 31, 2023.

GREENSPAN, S. E. et al. Low microbiome diversity in threatened amphibians from two biodiversity hotspots. Animal Microbiome. vol. 4, 69. dec. 29, 2022.

Republish