More than 1,000 pages distributed in two volumes, analyses of 26 researchers specialized in distinct cinematographic time periods and genres, which rebuild more than 100 years of national production. The book with these characteristics, Nova história do cinema brasileiro (New history of Brazilian film) (SESC, 2018), was organized by Fernão Pessoa Ramos and Sheila Schvarzman and provides a historiographic view of Brazilian cinema that addresses themes that are also very much a part of these first two decades of the 21st century, such as the role of women in society and issues related to gender or racial and ethnic minorities. The initiative was started by Ramos, researcher at the Art Institute of the University of Campinas (IA-UNICAMP) and author of other books about film.

“I felt there was a need for an up-to-date edition that was more complete,” he said, referring to the prior work, História do cinema brasileiro (History of Brazilian film; published by Círculo do Livro), which was 500 pages long and was published in 1987. “I wanted to think about the great themes and issues around Brazilian film, always valuing the historical perspective and its placement in the chronology,” explains Ramos, author of the text that, in the book, provides a snapshot of the period between the Cinema Novo movement and the so-called Revival, passing through the great crisis. In addition to filling the time gap, there was a concern with broadening the themes already addressed. “Knowledge about silent films, and consequently the section dedicated to the topic, grew. There are 200 pages stitched together by nine authors,” explains Schvarzman, a postgraduate professor in communications and history of Brazilian film at the Anhembi Morumbi University in São Paulo.

Copies provided by Fernão Pessoa Ramos

Born in Cairo, actress Eva Nill (1909–1990) stood out in productions by filmmaker Humberto Mauro (1897–1983)Copies provided by Fernão Pessoa Ramos“For the public in general, the fact that Brazil has produced silent films is not very well known. Many cannot even imagine that this happened. Yet, for us researchers, what was important was to bring to light everything that could be known from recent years,” said Schvarzman. The researchers identified the survival of 36 feature films and 218 documentaries (short films) until 1930. Together they estimate that these represent 10% of the production that Brazil was able to preserve. “Not all are intact. For some of the feature films, we were able to recover only some fragments that survived over time,” said Carlos Roberto de Souza, author of the chapter that talks about film in São Paulo, between 1912 and 1930, and professor with the Imaging and Sound Postgraduate Program at the Federal University of São Carlos (PPGIS-UFSCar).

At the beginning of the 20th century, the key film production centers were Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, cities with greater financial resources, which made “natural” films—as the cinematographic records are called for scenes of nature, urban landscapes, scientific demonstrations, political and social events. Between 1920 and 1930, cities such as Recife (Pernambuco), Porto Alegre and Pelotas (Rio Grande do Sul), Campinas (São Paulo) and Cataguases (Mato Grosso) also stood out with the so-called “regional cycles.”

According to Luciana Corrêa de Araújo, professor at PPGIS-UFSCar and author of the chapter that addresses film in Pernambuco at the beginning of the last century, in the second half of the 1920s, production in this northeastern state was particularly “robust and expressive.” Until now, research registers about 50 films produced in only six years, beginning in 1924, including short and feature films, nature, and fiction.

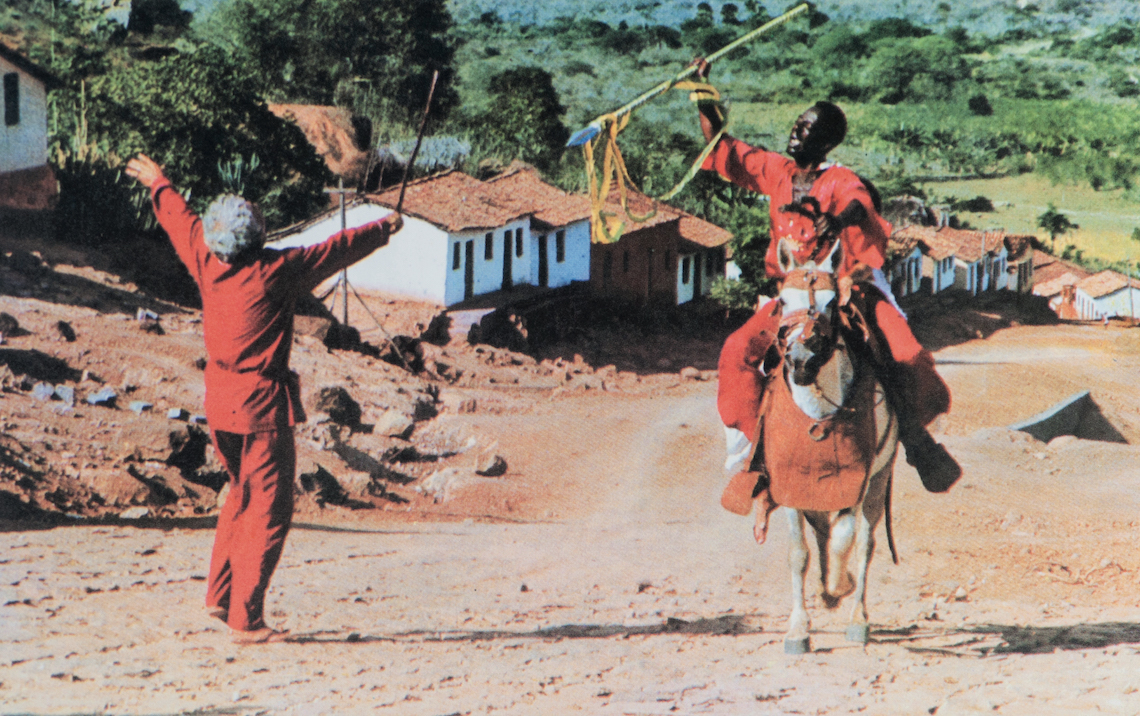

Copies provided by Fernão Pessoa Ramos

O Dragão da Maldade contra o Santo Guerreiro (The Evil Dragon vs. the Holy Warrior), directed by Glauber Rocha (1939–1981), joins the Abraccine list of top 100 Brazilian filmsCopies provided by Fernão Pessoa RamosNew approach

“Our approach is not restricted only to directors, but presents a broader analysis that includes exhibitors, the public, producers, box offices, and the screening rooms,” explains Ramos when pointing out that the intention of the project was to offer an overall view on the subject. “Film is not made by the lighting. We are not talking about poetry. It is about collective art which depends on a team, on the quality of the screening of its product, and on the receptiveness of the public,” explains Carlos Roberto de Souza.

1,118 pages

Seven sections

› The beginnings, silent film, and the beginning of audible film (1895/1935)

› Studios and independent producers (1930/1954)

› INCE and educational documentary film

(1937–1966)

› Cinema Novo, Cinema Marginal, and beyond (1955–1980)

› EMBRA and the mouth

› The great crisis and the revival (1985–2003)

› Contemporary Brazilian film

An example of this is the chapter “The beginnings of film in Brazil,” in which José Inacio de Melo Souza, retired researcher for Cinemateca Brasileira, describes the then innovative technologies that were being used, as in the case of the cosmoramas (boxes that imitated real scenes, such as landscapes of European cities, for example, beginning from a painted background and with the support of sculpted objects that confer a 3D perspective) and magical lanterns (made using lenses and a dark room). According to Melo Souza, the first screenings took place in Brazil in public places, such as streets and fairs, and they were organized by peddlers who carried the films in suitcases. The first time a film was shown on a proper screen was July 1896, on Ouvidor Street in Rio de Janeiro—the audience was exclusively comprised of journalists.

The minorities and prejudice

Before Nova história do cinema brasileiro (New history of Brazilian film) was written, Ramos and Schvarzman presented to their invited collaborators the principles they felt were fundamental to its creation. “We were concerned about delving into issues that had previously gone unnoticed by history and that now represent a trend in historiography,” said Ramos, referring to racism, the role of women, people of African descent, and indigenous peoples in the film productions. Such concern was not part of their 1987 book.

Copies provided by Fernão Pessoa Ramos

Wagner Moura in a scene of Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad), a police film directed by José Padilha (2007)Copies provided by Fernão Pessoa RamosSchvarzman remembers that prejudice was so entrenched in the past that these themes did not arouse attention. “There were few women directors of feature films in fiction,” writes Cleber Eduardo, curator of the now traditional Tiradentes Film Show, in Minas Gerais State. Two of the filmmakers he highlights include (from São Paulo) Ana Carolina, director of Getúlio Vargas (1974) and A Primeira Missa ou Tristes Tropeços, Enganos e Urucum (2014), and (from Rio) Lúcia Murat, winner of the Kikito for best film at the Gramado Festival, with Uma Longa Viagem (A Long Journey; 2011).

Racial issues are apparent in the small details. For example, in Thesouro Perdido (Lost Treasure), of 1926, film director Humberto Mauro (1897–1983), from Minas Gerais, shows a black boy with a lit cigarette in his mouth. In the following image, a frog does the same thing. “Comparing the mouth of a black boy with that of a frog is racism, regardless of whether or not the director intended it so,” assesses Schvarzman, author of the doctoral thesis about the work of Mauro.

Book delves into issues that comprise a trend in contemporary historiography

The 2000s

Romantic comedy, a genre that was not part of Ramos’s first book, earned an audience and significance in the more than three decades that separate the two books. “Many critics turned their noses at films such as De Pernas pro Ar (Topsy-Turvy; 2010) due to the clear popular appeal,” observes Schvarzman. She states that the film addresses sex, prejudice, and stereotypes of social relationships and drove 3.5 million viewers across the country to the movie theater.

The lead character, played by actress Ingrid Guimarães, is a woman who is devoted to her work and sees her life changed radically when her husband decides to leave home. Two years later, with De Pernas pro Ar 2 (Topsy-Turvy 2), Guimarães attracted an even larger paying audience: 4.8 million people. “The contemporary film explains a lot about Brazil—it reveals the interest in consumerism, the change in the role of women, and the interest in social climbing,” said Schvarzman. She believes that Brazilian film has taken to the big screen a current view of the country.

Some films led to the creation of network TV series, such as Ó Pai, Ó (2007), by Monique Gardenberg, and Divã (Divan; 2009), directed by José Alvarenga Júnior. Others have been successful on streaming sites, such as Se Eu Fosse Você (If I Were You; 2006), by Daniel Filho, and Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad; 2007), by José Padilha. It is about a new era in which the seventh art continues to adapt to the new possibilities of reproduction. “The platform changes, but the art continues to live, as what happened in every evolution that film has gone through—the arrival of color, of sound, and of digitalization,” states Ramos.

Projects

1. The staging of a documentary: Analysis and trial definition (nº 17/07597-3); Grant Mechanism Research Abroad; Investigator Fernão Pessoa Ramos (UNICAMP); Research Site University of Chicago (USA); Investment R$43,718.33.

2. South of the west – Theory and history of the documentary: Intersections between Australian and Brazilian Documentary Films (nº 16/14286-1); Grant Mechanism International Visiting Research Grant; Investigator Fernão Pessoa Ramos (UNICAMP); Visiting Researcher Deane Martin Williams (Monash University) Investment R$35,574.75.