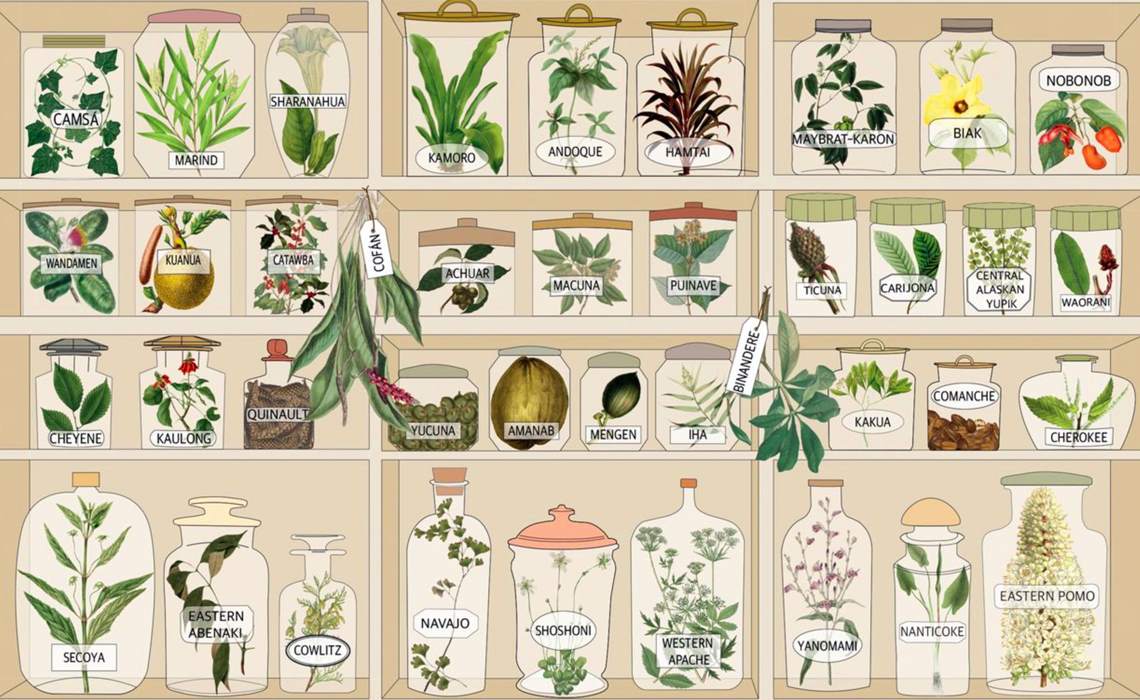

A considerable portion of human heritage is in danger of disappearing by the end of this century—an oral encyclopedia of medicinal practices in which the therapeutic and healing applications of thousands of plant species are catalogued. Irreparable losses of this knowledge have already occurred with the death of indigenous languages at a more drastic rate than the loss of biodiversity. These are some of the key conclusions that Spanish biologists Rodrigo Cámara-Leret and Jordi Bascompte draw in a paper published in June in PNAS.

In an interdisciplinary study, they intersected data on medicinal plants in three regions of high cultural and biological diversity (the west Amazon, including a portion in Brazil, a large dataset for North America, especially the US, and New Guinea) with data on the indigenous languages and linguistic branches in these regions to assess how knowledge of herbal medicine is distributed across linguistic groups, and to what extent languages contain unique, group-specific knowledge of medicinal plants. Their study shows, for example, that the Ticuna language, spoken by approximately 50,000 inhabitants of the Brazilian portion of the Amazon, encapsulates knowledge of more than 150 medicinal plant uses that is unique to this group. Ticuna has been classified as vulnerable by the Endangered Languages Project, an international initiative led by Google to identify and preserve languages at risk of extinction.

Cámara-Leret, a member of a research group led by Bascompte in the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, said he was surprised to “learn that more than 75% of indigenous knowledge in these regions is linguistically unique, or only known to one language.” In other words, at least three out of every four medicinal plant uses contained in traditional indigenous knowledge are encoded in a single language and in no other, with no overlaps or redundancy. “Even more surprisingly, we found that unique knowledge is more strongly associated with threatened languages than with threatened plants,” Cámara-Leret told Pesquisa FAPESP. This is especially significant at a time when environmental preservation efforts are increasingly focused on maintaining biodiversity, while often neglecting the importance of preserving biocultural diversity.

Glenn Shepard / MPEG

The Matsigenka also use certain plants to bathe their babies and protect them from the spirits of hunting animalsGlenn Shepard / MPEGIn determining whether medicinal properties are language-specific, the biologists used 20 broad medicinal categories such as digestive system, cardiovascular system or dental health. This means that if two languages describe a particular plant as a remedy for two very different conditions within the same broad medicinal category, then the relevant knowledge was considered to be shared across those languages. The researchers therefore believe their estimate of linguistically unique ethnobotanical knowledge is rather conservative.

There are more than 7,000 languages spoken in the world. About 30% of them will be extinct by the end of the twenty-first century. Urban expansion, continued colonization, deforestation, and cultural assimilation are the main culprits in this process of mass linguistic extinction. This trend is highly concerning given that traditional knowledge is often inextricably linked to the cultures, languages, and territories of the peoples who developed it. “Each language uses unique terminology to describe its surroundings, and when that terminology begins to erode, it’s as if the index to the forest library has been removed. This often happens when indigenous languages are replaced by more dominant languages that do not have established terms for plants in a particular region of the forest,” explains Cámara-Leret.

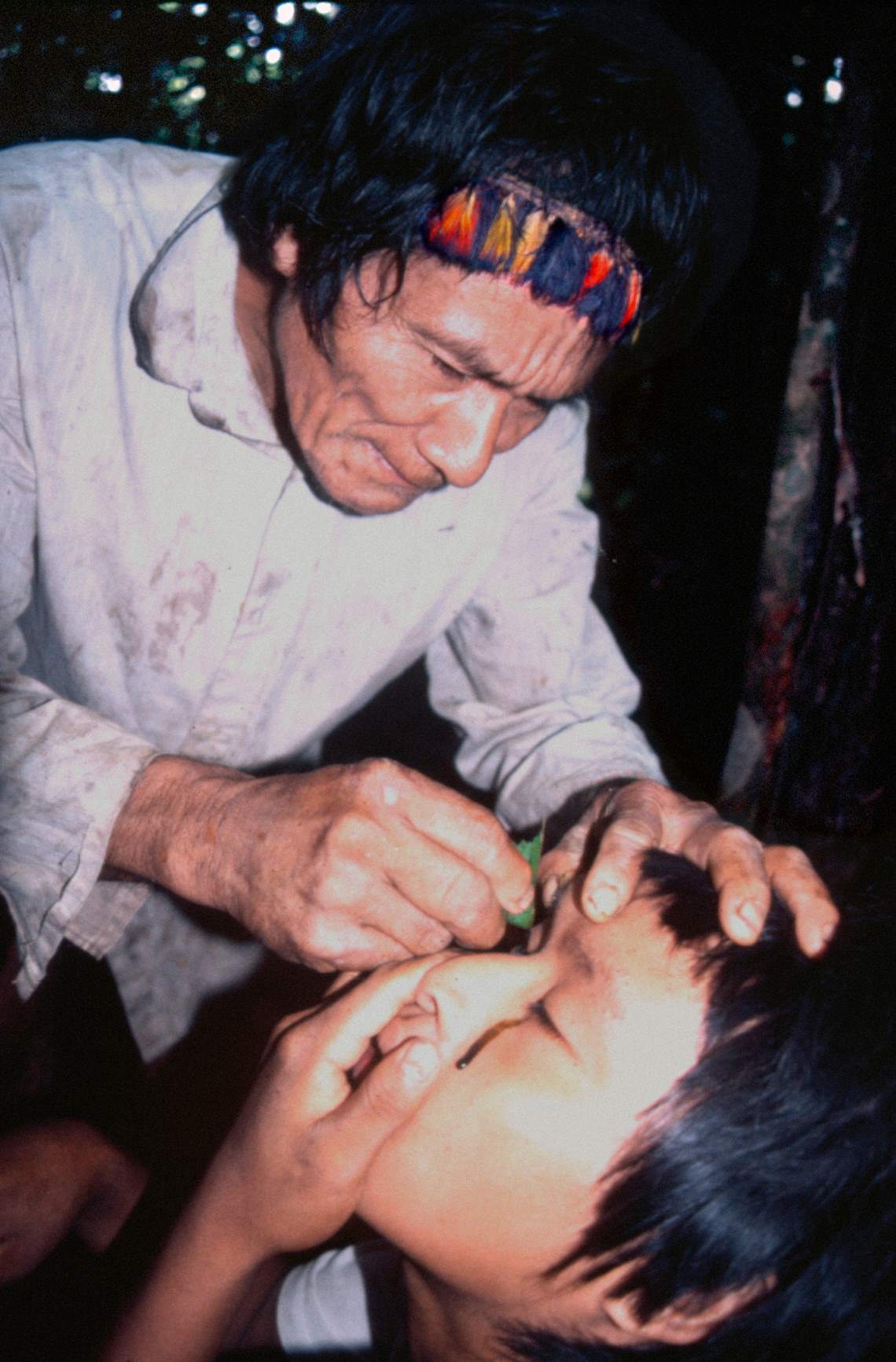

But the loss of environmentally adapted terminology is just one factor in the loss of ethnobotanical knowledge caused by language extinction. The death of a language and the breakdown of a culture entail the loss of a broader cognitive process. “Apprentices learn orally from their elders, and the knowledge they acquire includes myths, stories, and the names of places that need to be referred to in their own language in order to understand their place in the ecosystem and their connection with the land,” explains Cámara-Leret. “For example, the rituals required to become a traditional healer in northwestern Amazonia involve years of isolation during the day in the forest, and aspirants must sit at night with their elders in a maloca to learn the names of plants, their uses, myths, and their relationship with other beings and with diseases. Most of these rituals are lost when the associated languages are no longer spoken.”

Although the extinction of a language is one factor in the disintegration of a culture and a traditional body of knowledge, the relationship between these dimensions of the disappearance of human experiences is neither linear nor obvious. “Much of the ancestral knowledge held by certain indigenous peoples has been preserved because cultural practices continued even after the ancestral language was eventually abandoned,” says Wilmar D’Angelis, a professor of linguistics at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), who is leading an effort to preserve indigenous languages in the state of São Paulo and southern Brazil.

Glenn Shepard / MPEG

Jointed flatsedge (Cyperus spp.) is one of the most widely used medicinal plants among the Matsigenka people of Peru and other indigenous and traditional peoples in the AmazonGlenn Shepard / MPEGAlthough the linkage is not immediately obvious, D’Angelis believes a significant portion of traditional knowledge is reliant on ancestral languages, which use terminology that provides clues as to the nature and common attributes of different plants or animals. D’Angelis notes, for example, that Tupi names for plants or animals always describe unique attributes, whether morphological or functional, of their object. “This helps speakers of the language to not only identify the object itself, but to perceive traits that are shared in common by multiple objects.” D’Angelis cites plants of the Araceae family as an example. These plants have edible tubers and are called mangará in Tupi. Mangarataia stands for “mangará that burns,” which one might guess means ginger. Among medicinal plants, D’Angelis cites the acariçoba, a highly prevalent Amazon plant species known by indigenous peoples for its medicinal properties. The plant derives its name from the bald uakari, a red-faced monkey that the plant resembles.

Glenn Shepard Jr., a medical anthropologist at the Emílio Goeldi Museum of Pará, in Belém, argues that “a culture can survive without its associated language, or with the language in a dormant state, but maintaining the original language obviously helps to better preserve the knowledge of that culture. There are many examples of cultures thought to have become extinct that later reemerged.” He notes that while language and culture are usually intertwined, they are not one and the same thing. And while practices can survive the death of a language, languages can be culturally impoverished, with a resulting loss of knowledge of the environment in which they developed. “If indigenous people speak their mother tongue, we know their culture is being preserved with it. If they don’t speak their ancestral language, they can preserve their culture in other ways, but it becomes more difficult to sustain,” he says.

Shepard stresses, however, that “loss of language is the first step toward a loss of knowledge, which in turn leads to an ecological loss,” noting that efforts to preserve languages, traditional indigenous knowledge and biomes are interlinked. “The linguistic diversity map of Brazil overlaps its biodiversity map. Indian reservations help to preserve the language, the culture, and standing forests. Forests cannot be maintained without indigenous peoples living in them, speaking their own language, preserving their culture and their dietary traditions,” he explains. Cámara-Leret concurs: “Our findings underline the need to incorporate the cultural dimension and indigenous knowledge into current biodiversity conservation efforts, as most of the best-preserved areas in the world are on indigenous lands, where the vitality of their languages is central to conservation.”

Glenn Shepard / MPEG

Other plant remedies are applied directly to the eyes to enhance visual acuityGlenn Shepard / MPEGAn uncalculated loss

Languages are unique windows to the world and encapsulate the local human experience of a given culture. Studying each language can provide a better understanding of aspects surrounding the linguistic capabilities and cognition of the human species. That is why each language and each culture has an intrinsic value that warrants efforts to preserve it.

But the study by Cámara-Leret and Bascompte adds a new dimension: the mass extinction of languages and the consequent loss of traditional knowledge will undermine the discovery of treatments whose potential is still unknown to science. Only a very small portion (6%) of plant species has been screened for medicinal activity.

When a language is lost, and with it its associated library of medicinally active plants, the prospects of that ethnobotanical knowledge being rediscovered are poor. Indigenous peoples have been experimenting with plants for centuries in a forest with thousands of species, and “the likelihood of rediscovering this vast medicinal knowledge before plants and other regional languages are lost may be slim,” warns Cámara-Leret. He adds that the unlikelihood of rediscovery is compounded by sophisticated aspects such as indigenous knowledge about the preparation of plants, dosages, or combinations to produce synergistic effects.

The United Nations Organization for Education, Science, and Culture (UNESCO) has proclaimed the period between 2022 and 2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages. In designing approaches to language preservation, Cámara-Leret recommends “supporting local communities and language transmission from parent to child through government programs for bilingual education, community radios, and the preservation of indigenous cultures in each country.” Shepard points to the need to explore indigenous cosmologies for a deeper understanding of subtle and often overlooked attributes of plants. In a 2019 article in the journal Anthropology Today, in collaboration with British anthropologist Lewis Daly, he wrote that “plants and people are entwined in deep historical partnerships.” Each endangered indigenous language unrepeatably illuminates specific dimensions of those partnerships.

Scientific articles

CÁMARA-LERET, R. and BASCOMPTE, J. Language extinction triggers the loss of unique medicinal knowledge. PNAS. Vol. 118, no. 24, e2103683118. June 15, 2021.

SHEPARD JR., G. and DALY, L. Magic darts and messenger molecules: Toward a phytoethnography of indigenous Amazonia. Anthropology Today. Vol. 35, no. 2, p. 13–7. Apr. 1, 2019.