Three decades ago, children and adolescents became rights holders in Brazil. When Law No. 8,069, the Statute on Children and Adolescents (ECA) went into effect it began to secure “opportunities and facilities” that would provide them with “physical, mental, moral, spiritual, and social development, in conditions of freedom and dignity.” Since then, people from birth to age 18 are no longer viewed as either the occasional beneficiaries of charity and assistance, or objects requiring legal measures. Institutions were created and public policies have been adopted to guarantee their rights, affording changes that, in the estimation of experts, continue to have repercussions on multiple aspects of childhood in Brazil. The establishment of child protection and rights agencies led to the redistribution of decision-making power, which had previously been the sole mandate of judges. The implementation of mechanisms to make the adoption system more transparent, and the determination that adolescents who commit juvenile offenses should be sheltered in separate institutions from victims of abandonment are two distinct achievements. Yet challenges still remain, including the struggle against violence and the need to create strategies to give children and adolescents a voice throughout the legal process, among other issues.

Signed into law on July 13, 1990 by then President Fernando Collor de Mello, the ECA articulates and provides regulations for Article 227 of Brazil’s 1988 Federal Constitution. The statute is recognized as some of the first legislation in the world to adapt the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (UN) on November 20, 1989. The CRC entered into effect in September 1990 and became a legal instrument for promoting child protection, which was ratified by 196 countries. “Brazil taking a leading role in incorporating the principles of the convention into its federal legislation has made the country an international leader in CRC adaptation,” observes Mario Volpi, coordinator of the Adolescent Citizenship Program of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Brazil. He adds that the ECA inspired the creation of similar legislation in at least 15 countries in Latin America, including Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay. Like Brazil, by adopting the CRC regulations these countries have also accomplished important achievements such as reducing infant mortality and expanding access to education.

“The ECA contains 236 articles. Half of these have already been modified, always in the direction of expanding their reach,” says Roberto da Silva, a professor at the School of Education of the University of São Paulo (FE-USP). The ECA topic that has been modified most concerns family and adoption issues. “Until 2005, Brazil was listed as one of the world’s largest exporters of children for adoption. That situation began to change due to guidelines established by the statute,” adds Silva, who lived in shelters from the age of five on, and has since worked at the State Foundation for the Welfare of Minors (FEBEM) and the prison system. Today, he coordinates a research group and teaches courses on ECA theory and practice.

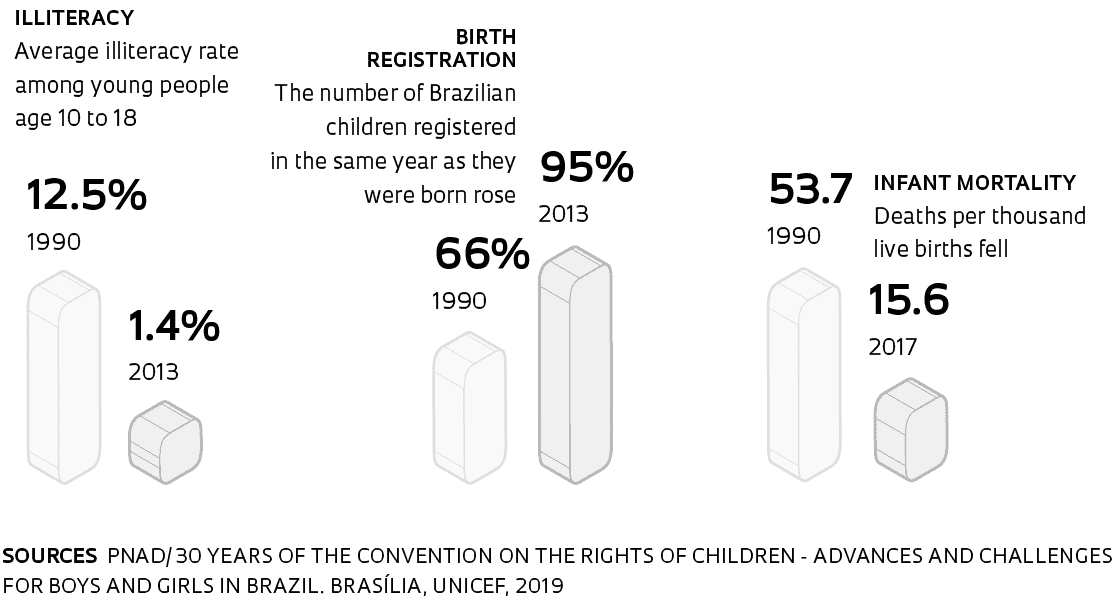

A UNICEF assessment of the 30 years the Convention on the Rights of the Child has been in effect points out that Brazil’s constitution was adopted at a time when the country, like other developing nations, faced serious problems with the trafficking, sale, kidnapping, and theft of children, who were peddled on the illegal international adoption market. When the ECA went into effect, it became mandatory for each district to register adults qualified to adopt children, as well as children available for adoption. Keeping children in the country became a priority. In 2009, in the wake of these changes, Law No. 12,010, also known as the National Adoption Law, modified 54 of the ECA’s articles. In addition to the existing district-level registrations, state and national registration also became mandatory. “The adoption system has become more transparent and has begun to follow rules that avoid discrimination. It’s no longer possible, for example, to cut in line to speed up an adoption process,” observes Rubens Naves, a lawyer and retired professor from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo Law School (PUC-SP). This only became viable, he points out, to the extent public policies were adopted to ensure the rights established by the ECA, such as actions to expand vaccination coverage and encourage breastfeeding, which contributed to reducing infant mortality (see data at right).

In relation to recent changes incorporated into the statute, Josiane Rose Petry Veronese, a tenured professor of Child and Adolescent Law at the Federal University of Santa Catarina Law School (UFSC), highlights that the National Adoption Law also established that termination of family rights cases, which could make a child available for adoption, cannot extend beyond 180 days. Statistics indicate that children under 6 are more easily adopted, while beyond that age finding homes for them becomes increasingly difficult. “Streamlining the legal process of termination of family rights increases their chances for adoption,” states educator Amanda Rodrigues de Souza Colozio. In her doctoral research in special education at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) she is studying the circumstances of children and adolescents sheltered in childcare institutions with high psychomotor, socioemotional, and intellectual capacities, among other factors. “As part of my doctoral research, I am following a 13-year-old student with a high learning capacity who has been removed from his biological family by social workers since the age of 8 because of his mother’s chemical dependency. Today, he lives in a childcare institution and is on his fourth attempt at reintegration, with the high probability he’ll be permanently removed from his family. Since he’s already a teenager, his chances of being adopted are minimal,” she laments.

In Brazil, the history of caring for children and adolescents in childcare facilities stretches back to the colonial period, when Jesuit priests founded institutions to receive indigenous people. Beginning in 1825, the Santa Casa de Misericórdia (Holy House of Mercy) in São Paulo began to operate what was then called a “foundling wheel,” a kind of rotating platform installed in an external wall to receive unwanted children. According to data from the institution, during the time it was in operation, until 1950, the foundling wheel had received about 4,600 babies. Colozio observes that before the ECA the 1979 Minors Code provided for the protection and supervision of minors with legal issues, albeit from a punitive and paternalistic approach. There was no distinction made between abandoned children, orphans, truants, and adolescents in conflict with the law. All received the same treatment: they were sent to institutions where they remained interned, under state supervision.

“The laws that preceded the statute stipulated measures to prevent or rehabilitate youth from situations of delinquency. Because it considered that abandoned children and adolescents had the potential to be involved in juvenile offenses, they were interned to the same degree as those who actually committed crimes,” explains sociologist Bruna Gisi, a professor at the USP School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH-USP), who has researched juvenile justice for more than 10 years. Gisi explains that the ECA brought about a change in this framework, by differentiating those who commit juvenile offenses from adolescents who are the victims of rights violations. Juliana Vinuto, from the Department of Public Safety at Fluminense Federal University (UFF), notes that the Minors Code established the existence of large detention complexes, such as FEBEM, which sheltered thousands of adolescents with legal problems in São Paulo until its closing in 2006. “Before ECA, young people were seen as an object of intervention. They were placed in detention units for various reasons. The objective was to change them, often through the use of violence,” she adds. The ECA established that detention units, exclusively for those accused of juvenile offenses, can house a maximum of 90 teenagers, but this is not always observed. Many institutions face overcrowding problems.

Léo Ramos Chaves

Léo Ramos Chaves

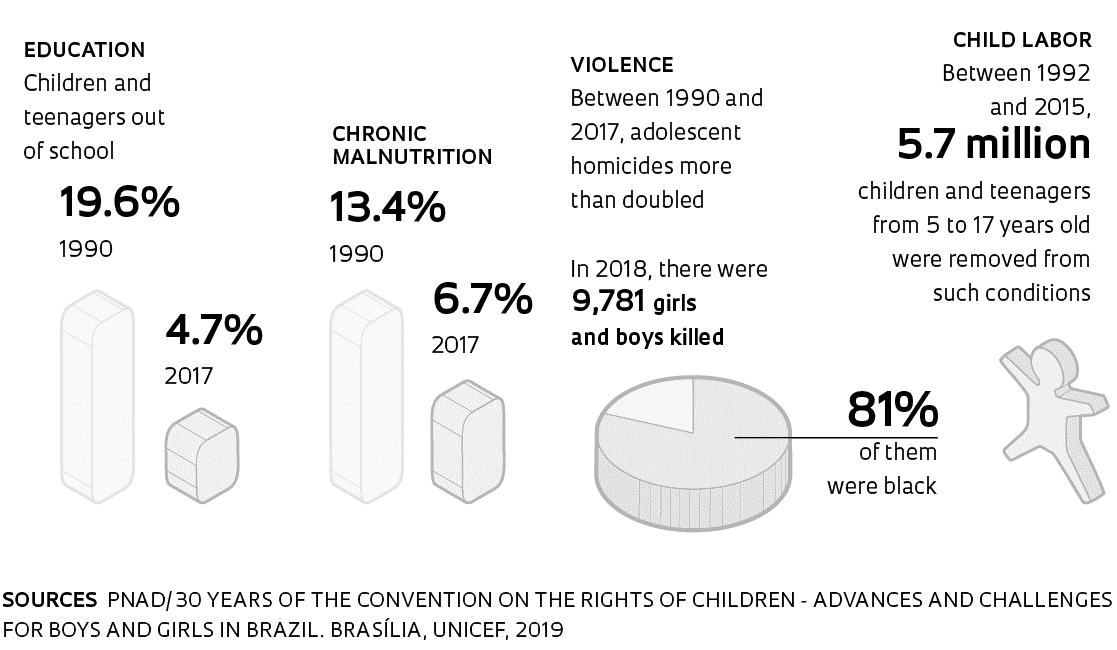

To ensure a safety net that operates as intended by its legal framework, over the past 30 years the ECA has promoted the creation of institutions such as child protection agencies and rights advisory councils for children and adolescents. “By having their members chosen from within the community, these agencies opened up the possibility for civil society to participate in decision-making,” says Vicente de Paula Faleiros, who trained in law and social work and is a retired tenured professor from the University of Brasília (UnB). The primary responsibilities of the child protection agencies include implementing protective measures for children and adolescents who are victims of violence, referring complaints regarding rights violations, establishing provisions for compliance with protective measures determined by the courts, requisitioning birth and death certificates, and oversight of conditions in childcare institutions. One example of how these changes have helped protect young people comes from Jardins, an upscale neighborhood in São Paulo. Motivated by complaints from residents and businesses, at the end of August the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) called on the child protection agency to investigate cases of child labor in the region. According to the MP, the pandemic has aggravated conditions in the city—from May to July there was a 26% increase in the number of recorded cases.

“Before the statute, juvenile court judges, now called childhood and youth court judges, held 100% of the decision-making power in civil and criminal cases involving children and adolescents,” observes Roberto da Silva, from FE-USP. With the advent of the statute, which stipulated the creation of municipal councils and protection agencies for children and adolescents, the situation changed completely. Today, practically every municipality in the country has such an agency, whose function is to guarantee respect for the rights of those under age 18. According to Silva, the councils were fundamental in the effort to redistribute decision-making power among different societal institutions. “By doing that, the statute removed 80% of these powers from the hands of judges,” Silva estimates. Today, judges can rule on cases of changes in custody or guardianship, and on juvenile offenses. “All other matters involving children are now being arbitrated by institutions within civil society or the government,” he adds. During her doctoral work, Gisi, from USP, conducted field research at the Brás Special Courts for Children and Youth, in São Paulo. “I interviewed some judges and followed several hearings and observed that not all of them maintain a discourse that’s in tune with ECA principles, adopting a more repressive and punitive rationale when making decisions,” she notes.

A children’s rights researcher for more than 20 years, Faleiros says that most reports of sexual abuse are referred to the child protection agencies, which are also qualified to require children’s attendance in schools. “The ECA’s contribution to increasing access to education has been crucial,” observes Volpi, from UNICEF (see data at left). “While before the ECA it was necessary to resort to court procedures to enroll a child who wasn’t attending school due to the negligence of their legal guardians, today one simply calls the child protection agency, which can perform registrations and take the measures necessary to place the child in school,” he explains. These agencies are also tasked with participating in the municipality’s budget planning for the development of education, health, social assistance, and public safety policies concerning children and adolescents.

In addition to the improved status given to children and adolescents, the adoption of the ECA also placed Brazil in the spotlight because it was one of the first laws in the world to permit litigation regarding the social rights of younger citizens in areas such as health and education. UNICEF’s assessment indicates that since the statute went into effect, court rulings have begun to ensure that the government provides prostheses and orthoses, guaranteed the hiring of sign language teachers and assistants for autistic and disabled children in public schools, and expanded the availability of daycare. And in the assessment of attorney Rubens Naves from PUC-SP, therein lies one of the legislation’s greatest benefits. He notes that because of the ECA, as of 2011, mothers with children who don’t have access to early childhood education were able to begin suing the city of São Paulo to create places for their children. Such initiatives had a significant impact on reducing the waiting list, says Naves, who is also a member of the advisory committee for the Childhood and Youth Agency of the São Paulo State Court System (TJSP). In 2016, more than 103,000 children were still awaiting placement in daycare centers in the city. Another 3,400 were waiting to be enrolled in preschool, according to data from the Municipal Education Department (SME). In July this year, the waiting list for placement in daycare centers was down to 22,300 children, according to data from the SME.

The recognition of children and adolescents as rights holders mobilized the state to establish public policies to ensure compliance in various arenas. In education, the advances are evident: and the approval of the National Education Plan in 2014, which established 20 goals to improve public education throughout the country by 2024. Thus, although in 1990 almost 20% of children ages 7 to 14 (the mandatory age group at the time) were not attending school, by 2018, only 4.2% of children in the same age group were out of school, according to a UNICEF report based on data from the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD). The report also indicates that there was a significant drop in the average illiteracy rate among the 10 to 18 age group: from 12.5%, in 1990, to 1.4%, in 2013.

Léo Ramos Chaves

Léo Ramos Chaves

Despite progress, the treatment of young people in conflict with the law still faces challenges, says Vinuto, at UFF. She states that only 15% of the adolescents held in socio-educational care centers committed crimes of homicide or rape. The majority are serving time for theft or drug trafficking, offenses that according to the ECA do not allow for internment in socio-educational care centers. Another problem involves the idea of socio-education itself, which originated along with the statute to provide for the development of linked educational and social programs, which allow young people to rebuild their lives and plan their futures. One of the key functions of socio-education is to ensure that adolescents remain in school. However, according to the findings in Vinuto’s doctoral thesis, in practice this is often unfeasible due to overcrowding and the scarcity of material conditions at educational institutions.

The treatment of offenders is only one aspect that might be improved. Another, in the view of UFSC’s Veronese, involves the need to create new mechanisms through which children in violent environments can be heard in legal proceedings. Since 2017, Law No. 13,431, known as the Specialized Listening Law, has motivated municipalities such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Florianópolis to create specific physical spaces within the Child and Youth Courts. Psychologists and social workers have been hired to ensure that participation is conducted appropriately, avoiding situations in which a child feels intimidated or is required to repeat their testimony several times. Another difficulty concerns physical punishment, which was permitted by the Civil Code until 2002, but expressly prohibited since the enactment of the Boy Bernardo Law. “One attitude that’s still firmly entrenched is the idea that it’s possible to overpower children’s bodies using violence to correct behaviors or educate them,” she observes.

Léo Ramos Chaves

Léo Ramos Chaves

The arrival of the pandemic has exacerbated this situation. In Brazil, according to the portal of the National Ombudsman for Human Rights, which gathers data from the Dial 100 and Dial 180 services [hotlines for violence against children and teenagers, and women, respectively], violations of the rights of children and adolescents have increased in recent months. From March through May, Dial 100 registered 85,200 complaints, an increase of 11% compared to records from January through June 2019. More than 70% of cases of sexual violence are committed by victims’ relatives. In addition, with schools closed and the worsening of family living conditions, child labor, which had shown significant reductions since the ECA (see data at left), has recently been on the rise. “Investment is urgently needed to guarantee safe conditions for reopening schools, by analyzing epidemiological conditions in each region, establishing adequate sanitary conditions, and preparing students and education professionals to safely resume teaching activities,” she argues. Volpi adds that UNICEF, in partnership with the Union of Municipal Education Directors (UNDIME) and the National Council of State Secretaries of Education (CONSED), is analyzing which states meet conditions for reopening their educational institutions. “The ECA is very clear about one principle: that to ensure one right, you can’t violate another. In other words, the right to health is as important as the right to education,” he concludes.

Paradoxes of juvenile justice

In the United Kingdom, the first institutions dedicated to the criminal liability of children and adolescents and receiving abandoned individuals were created in the middle of the nineteenth century. These were followed by the establishment of the first juvenile courts, as a result of the Children Act of 1908. In a study conducted from 2017 to 2018 at King’s College London, in England, sociologist Liana de Paula, from the School of Philosophy, Language and Human Sciences at the Federal University of São Paulo (EFLCH-UNIFESP), studied recent changes in the history of juvenile justice there, comparing it with the situation in Brazil. In 1927 the first Minors Code in Brazil proposed measures to ensure that the children of poor workers didn’t “wander” the streets of cities and were instead sent to institutions that prepared them to become part of the work force. “In the United Kingdom, until the end of the twentieth century, juvenile justice developed based on the idea of providing social welfare as a way to prevent delinquency. Since the end of the nineteenth century, young people were judged and dealt with in a different system than adults,” she notes. However, in 1993, the murder of James Bulger, a boy who was not yet two years old, by two 10-year-old children, provoked a reinterpretation of the British system, which began to adopt a punitive approach that was no longer oriented around the idea of protection. Since then, through changes made to federal legislation regarding certain crimes young people can be tried and convicted with the same sentences as adults. “With the tougher legislation, more adolescents have been imprisoned since the 1990s, which generated an increase in recidivism, in addition to multiplying the government’s costs in maintaining the system. Because of these problems, today England is looking for ways to rethink its juvenile justice framework,” she explains.

Republish