The demands of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transvestite, and transgender (LGBT) communities have never been resolved through the legislative process, by passing bills. The majority of LGBT rights in Brazil were acquired through legal actions taken up by the judicial branch. Lawsuits filed in state courts were moved up to the superior courts and eventually arrived at the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court (STF), according to studies by sociologist Gustavo Gomes da Costa Santos, a professor at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE). This was the path taken by the legalization for same-sex civil unions, which received legal recognition by the STF in May 2011. Other legal actions involving the donation of blood by gay men, and changes in the legal names of transgender individuals are currently awaiting judgment by the STF.

Gomes da Costa adds that these demands usually follow a very similar course in countries as different as the United States and South Africa. “There is a trend happening worldwide in which judicial courts have taken the leading role in procedures which recognize the rights of this niche of society,” said the researcher, who coordinates the Diversiones Research Group—Human Rights, Power, and Culture in Gender and Sexuality, under the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). According to him, this is because these demands face resistance from conservative groups within state and federal legislatures. “In Brazil, the Evangelical Parliamentary Front, and House members with ties to the Catholic Church are often the main opponents of this type of legislation,” he says.

The process of recognizing a “stable union” [a type of national, legally recognized common-law marriage] for same-sex couples was linked to the impact of the arrival of AIDS in Brazil, where the first cases were recorded in 1982, says anthropologist Regina Facchini, coordinator of the Pagu Gender Studies Center of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). “In the 1980s, AIDS deaths among gay men were very common. In numerous cases, surviving partners even lost the home they lived in because the relationship wasn’t legally recognized. The process of recognizing the stable unions of same-sex couples was initially related to this type of situation and sought to guarantee pension, retirement, or inheritance rights,” Facchini says.

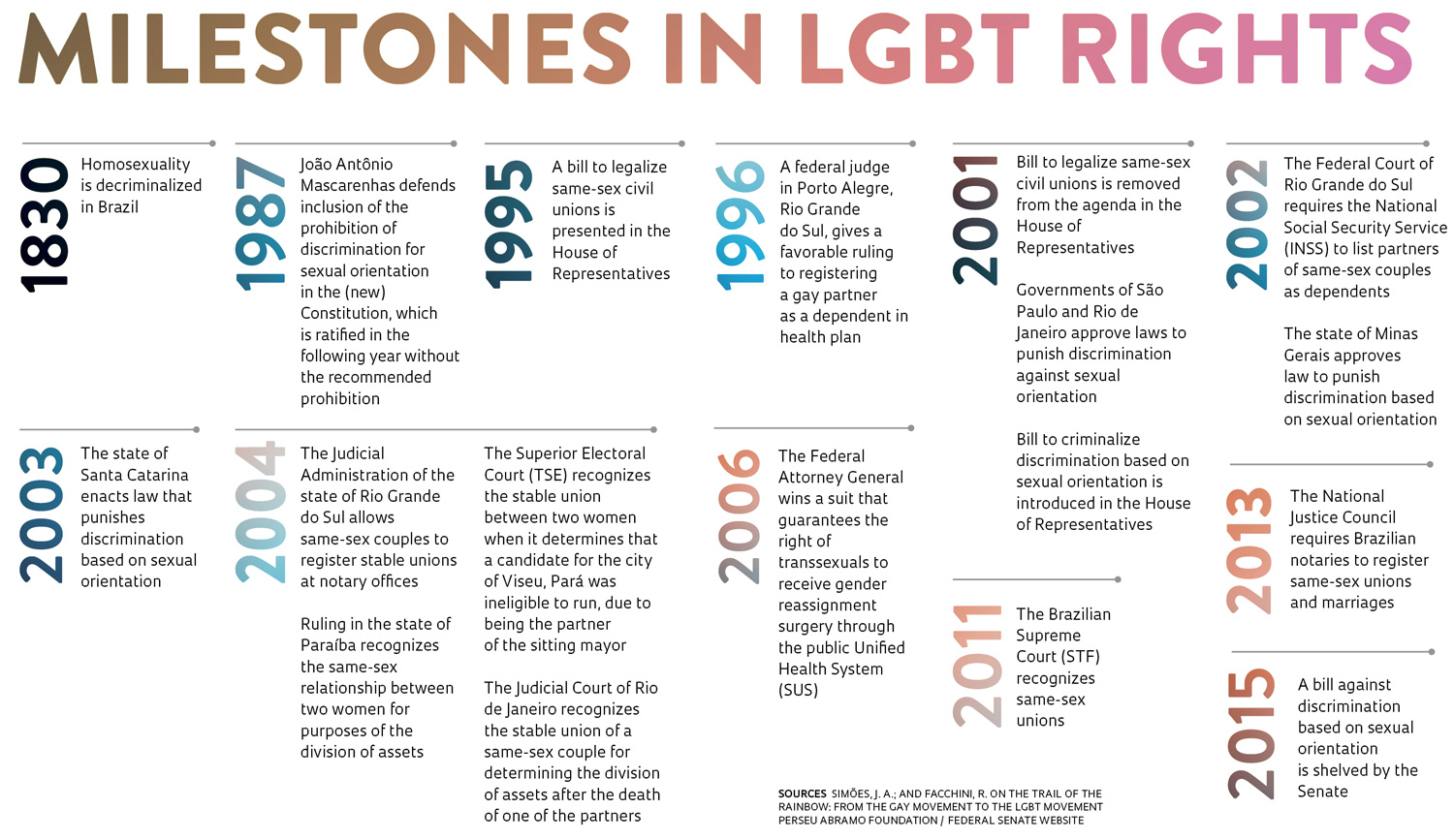

In order to meet these demands, the first attempt to legalize same-sex civil unions was made in 1995 through House Bill No. 1151, authored by then congressional representative Marta Suplicy. Presented in the Brazilian House of Representatives in October of that year, the bill’s principal spokesperson was Representative Roberto Jefferson, who proposed the recognition of “registered civil partnerships”—not unions—in addition to vetoing the adoption of children by these couples.

Gomes da Costa, from UFPE, explains that at that time the Brazilian Constitution was interpreted as establishing that unions were valid only between men and women, so the phrase proposed by Jefferson sought to facilitate a way through legalization. “If the bill had kept the term “civil union,” it would have resulted in a request for a change to the Constitution and the risk of it being voted down would have been greater,” says Gomes da Costa, who notes that the bill was approved in a house committee, but never got put to a full vote. “Bill No. 1151 was removed from the agenda in 2001, after an agreement among house leaders,” says the researcher, who has studied every legislative initiative that addressed the LGBT community, starting from when the civil government was restored in 1985 up through 2012. In 2011, Marta Suplicy, by then a recently elected senator, filed Senate Bill (PLS) No. 612/2011 to request legal recognition for stable unions between same-sex couples. The bill’s vote was postponed at the end of last year.

Although state and federal court cases became more frequent after the 1980s, it wasn’t until the 1990s that the judiciary began to perform a significant role in guaranteeing rights for the LGBT community, when the first rulings favorable to the recognition of same-sex couples were handed down. “People entered the state courts to have their unions recognized in order to receive their pension, inheritance, or retirement, then the judges denied their claims, they appealed, and the lawsuits proceeded to the superior court,” explains Gomes da Costa. One of the pioneering decisions came in July 1996, when federal judge Roger Raupp Rios of Porto Alegre gave a favorable ruling to registering a gay male partner as a health care dependent (see sequence of cases).

The issue of recognition of same-sex couples reached the STF in 2008. That year, the Rio de Janeiro State Attorney’s Office filed a civil suit with the STF—Arbitration for Non-Compliance with a Fundamental [constitutional] Precept (ADPF), No. 132—regarding the regulation of pension rights of its employees. “The government of Rio de Janeiro consulted the STF to determine whether it should recognize pension claims by partners from same-sex couples,” says Thiago de Souza Amparo, a professor at the School of Law of the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV).

Stable union

Stable union

During the STF’s analysis of the case, Deborah Duprat, the interim federal attorney general, submitted that the court recognize same-sex stable unions through a new civil suit—the Direct Action of Unconstitutionality (ADI), No. 4277—inasmuch as the legal opinion of the Federal Attorney’s Office maintained that the effects of ADPF 132 would be restricted to the state of Rio. Duprat argued that the mandatory recognition of stable unions between same-sex couples should be drawn from the Constitution itself, by analogous duplication of the standards considered valid for stable unions between men and women. In May 2011, the STF applied this interpretation of the Constitution to Article 1723 of the Civil Code, which deals with the legal framework of stable unions, equating same-sex unions with heterosexual unions. “The Supreme Court judges interpreted the Constitution differently than did Roberto Jefferson in 1995, arguing that the document was not restrictive to couples made up of men and women and citing that situation as only one example of a family unit,” explains the FGV professor. Even after the STF’s decision, some notary offices refused to register the stable unions of LGBT couples, which led the National Justice Council to issue a ruling forcing them to carry out the procedure.

According to Gomes da Costa, after the Court’s decision, the formalization of same-sex unions—which previously only happened under specific circumstances—became frequent in Brazil. In 2017, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) released the Civil Registry Statistics, reporting that since 2013 registration of same-sex marriages grew 51.7%, while stable union applications rose 15.7%. In addition, the UFPE researcher notes that the decision also cut the bureaucratic red tape for adoption procedures by these couples. Previously, some judges had alleged that same-sex partners didn’t live in a stable union and weren’t married, criteria fundamental to authorizing the adoption of children in accordance with the Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA).

Criminalization of homophobia

Another demand of the LGBT community that has gained traction in the state and municipal legislative spheres since the 2000s is the criminalization of homophobia. Data from the Brazilian Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transvestite, Transsexual, and Intersex Association (ABGLT) indicate that in 2004, about seventy cities and nine Brazilian states had some type of law to combat discrimination based on sexual orientation. This is according to the book Direitos e políticas sexuais no Brasil: Mapeamento e diagnóstico (Sexual rights and policies in Brazil: Survey and diagnosis), published by the Center for Studies and Research on Collective Health (CEPESC), and the Latin American Center for Sexuality and Human Rights (CLAM) of the State University of Rio de January (UERJ). Anthropologist Sérgio Luís Carrara, professor at UERJ and a researcher at CLAM, explains that these laws may involve punishment for discrimination in commercial establishments and real estate purchase or rental transactions, or may reach even further, including such situations as on-the-job prejudice or discriminatory hiring practices. “However, the laws establish fines or sanctions, but don’t penalize the accused in the criminal courts, something that will only be possible when Brazil has a federal law that criminalizes homophobia,” Carrara says.

Cases under analysis

There are three cases pending in the STF regarding LGBT rights scheduled to be decided this year. The first involves a transsexual woman who claims the right to use toilets designated for the gender that she herself identifies with. The second—a combination of two lawsuits—is a suit regarding changing the name and legal gender of transsexuals on civil registration documents, without the requirement to perform sex reassignment surgery.

The third case concerns blood donations by men who have sex with other men, who are currently prohibited from giving blood for 12 months following the sexual act. During the last session held to discuss the issue, which took place in late 2017, all the judges voted to allow blood donation by this portion of the population without restrictions. However, with his vote, Judge Alexandre de Moraes stressed the need for the blood to be stored for three months, and to undergo tests to detect the presence of HIV after this incubation period. The STF has not yet decided the case.

“In recent years, the court has been called to debate issues that have historically been brought to the legislative branch. However, the Supreme Court can’t keep up with so many cases, such that the lawsuits can frequently take years to be heard,” comments the FGV researcher. Amparo believes that in cases that meet with considerable societal resistance, such as those related to the LGBT community, this delay may work in favor of allowing public opinion to mature, so that the judges’ final ruling will be more widely accepted. “The cost, on the other hand, is the damage being done to the constitutional rights of the parties involved in these legal proceedings, due to the slow pace—intentional or not—of the Supreme Court,” he concludes.

Scientific article

GOMES DA COSTA SANTOS, G. Movimento LGBT e partidos políticos no Brasil. Contemporânea— Revista de Sociologia da UFSCAR. Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 179–212, Jan.–Jun. 2016.

Books

SIMÕES, J. A. and FACCHINI, R. Na trilha do arco-íris: Do movimento homossexual ao LGBT. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo. 2009, 194 pages.

VIANNA, A. and LACERDA, P. Direitos e políticas sexuais no Brasil: Mapeamento e diagnóstico. Rio de Janeiro: CEPESC. 2004, 246 pages.