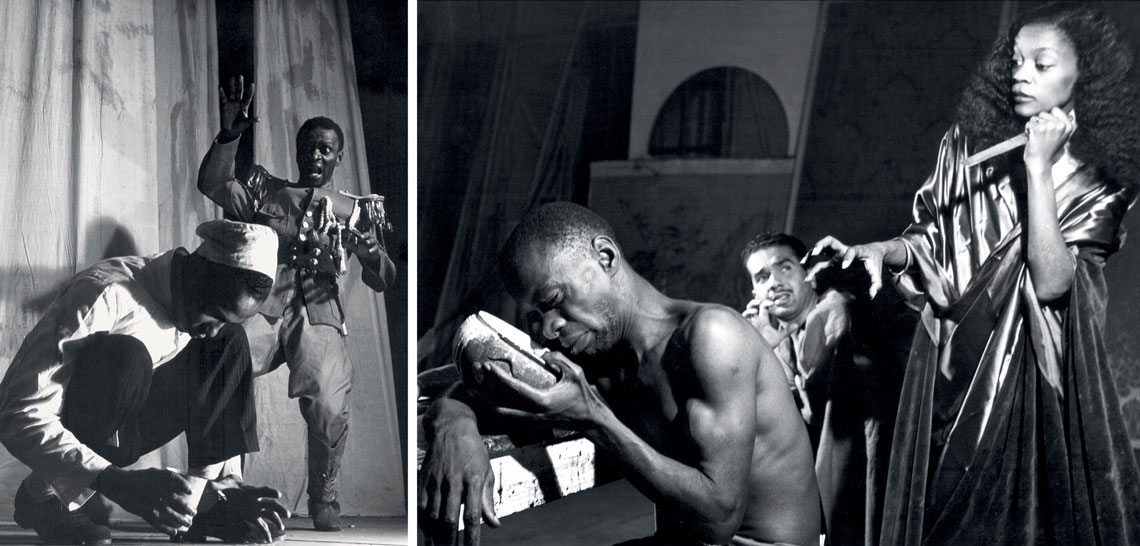

José Medeiros / Abdias Nascimento Collection / IpeafroNascimento as Othello in the 1940sJosé Medeiros / Abdias Nascimento Collection / Ipeafro

On May 8, 1945—the same day Nazi Germany surrendered and World War II came to an end—Brazil witnessed a milestone of its own. In Rio de Janeiro, the grand stage of the Municipal Theater welcomed, for the first time, a production featuring a Black lead and a majority Black cast—a radical break from the norms of Brazil’s performing arts scene. The play was The Emperor Jones, written by American playwright Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953), with Aguinaldo Camargo (1918-1952) starring in the title role. The drama follows an African American man who, after committing a murder, escapes to a Caribbean island and seizes power as emperor.

This historic performance marked the debut of the Black Experimental Theater (TEN), founded a year earlier in Rio by playwright, actor, and director Abdias Nascimento (1914-2011). “It was the end of the era when blackness was synonymous with mockery on the Brazilian stage,” Nascimento would write five decades later, in a 1997 article for Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. He was referring to the entrenched practice in Brazilian theater of assigning Black performers only minor or caricatured roles—“ridiculous, mischievous, and pejorative,” as he described them. Major parts were typically reserved for White actors performing in blackface.

From then on, TEN became a key platform for training and launching black actors who would go on to become major names in Brazilian theater, including icons like Ruth de Souza (1921-2019) and Léa Garcia (1933-2023). One of the company’s most symbolic moments came in 1949 during the Shakespeare Festival at the Fênix Theater in Rio. A scene from William Shakespeare’s Othello (1564-1616) was performed by two Black actors—Souza and Nascimento—as Desdemona and Othello.

“The presence of Black artists in Brazilian theater merits more in-depth study,” says Leda Maria Martins, a retired professor of literature at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). “In the eighteenth century, Black people performed all kinds of roles, as acting was then seen as a low-status occupation. But by the nineteenth century, Black performers were increasingly pushed to the margins, reduced to highly stereotyped, secondary characters.”

According to Martins, the theater company founded by Abdias Nascimento made important contributions to modernizing Brazilian theater—though its influence has often gone unrecognized. “Abdias was a pioneer, for instance, in bringing performative elements rooted in African traditions into his productions, especially ritual gestures from Candomblé,” explains Martins, whose doctoral thesis, “A cena em sombras: Expressões do teatro negro no Brasil e nos EUA” (A scene in shadows: Expressions of Black theater in Brazil and the US), defended at UFMG in 1991, was one of the earliest academic studies on TEN.

José Medeiros / Instituto Moreira SallesA rehearsal of the Black Experimental Theater in 1944, with actor Grande Otelo in the center, wearing a tieJosé Medeiros / Instituto Moreira Salles

With few existing plays depicting the Black experience in Brazil, TEN began to commission and stage Brazilian works such as O filho pródigo (The prodigal son; 1947) by Lúcio Cardoso (1912-1968), O anjo negro (Black angel; 1946) by Nelson Rodrigues (1912-1980), and Sortilégio, mistério negro (Sortilege, Black mystery; 1951), written by Nascimento himself. The nine original plays created for TEN were eventually compiled into the anthology Dramas para negros e prólogo para brancos (Dramas for Blacks and a prologue for Whites), first published in 1961 and recently reissued by publishing house Temporal.

“Many of the plays written for TEN reveal Black protagonists’ desire to ‘whiten’ themselves,” observes Martins, who also wrote the anthology’s preface. “In those narratives, the whiter one’s skin, the greater the chance of moving up the social hierarchy. Interracial relationships also feature prominently,” she adds. “It may sound contradictory, but this was a reality of the time—a period when eugenic ideas were still circulating widely across Brazil. In the early twentieth century, the national ideal was to become White, a belief voiced even by celebrated, highly influential intellectuals like Monteiro Lobato [1882-1948].”

The idea of staging a predominantly Black cast in Brazilian theater wasn’t an entirely new one. Some two decades earlier, actor, director, and playwright De Chocolat (1887-1956) had established Companhia Negra de Revistas in Rio de Janeiro, active from 1926 to 1927. Yet no initiative came close to matching the influence of TEN. Even with limited resources, TEN extended its mission to include literacy and cultural programs for the Black community, attracting factory and domestic workers.

TEN’s success also inspired other initiatives, like the Black theater company Teatro Experimental do Negro de São Paulo (TENSP), founded in 1945 by professor and journalist Geraldo Campos de Oliveira. “Both TEN and TENSP were made possible by the democratic opening that followed the end of the Estado Novo dictatorship [1937-1945] and lasted until the military coup of 1964,” says Mário Augusto Medeiros da Silva, a sociologist at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and an expert on Brazil’s Black movement. “It’s no coincidence that after 1964, both companies collapsed. The military regime [1964-1985] viewed antiracist activism as subversive and worked aggressively to silence these efforts.”

José Medeiros / Abdias Nascimento Collection / IpeafroFrom left: scenes from The Emperor Jones (1945), with Aguinaldo Camargo (standing), and O filho pródigo (The prodigal son; 1947), with Ruth de SouzaJosé Medeiros / Abdias Nascimento Collection / Ipeafro

TEN’s debut at the Municipal Theater in Rio was also a turnaround in Nascimento’s personal life. Just two years earlier, in April 1943, he had been imprisoned at São Paulo’s infamous Carandiru penitentiary. At 29, Nascimento landed in jail after standing up to a racist incident alongside his friend Sebastião Rodrigues Alves in the 1930s. Both men, then serving in the Brazilian Army, had been barred from entering a nightclub through the front door and clashed with an officer from São Paulo’s State Department of Political and Social Order (DEOPS-SP).

Expelled from the Army over the incident, Nascimento later traveled in 1941 to the Amazon and to Peru with Santa Hermandad de la Orquídea, a group of Brazilian and Argentine intellectuals. In Peru, he watched The Emperor Jones performed by a White actor in blackface. It was there that he conceived the idea of founding a Black theater company in Brazil. But on his return, he learned he had been convicted in absentia for his part in the earlier altercation.

While imprisoned at Carandiru, Nascimento cofounded Teatro do Sentenciado with fellow inmates—a theater group composed entirely of convicts, which organized six productions in total. During his time behind bars, he also wrote Submundo: cadernos de um penitenciário (Underworld: A prisoner’s log), a memoir-like account chronicling the lives of other notable inmates, such as Lino Catarino, and documenting the challenges of organizing a theater company behind bars. The manuscript was finally published in 2023 by Zahar.

“They created their own scripts and handled every detail—from costumes to lighting,” says Viviane Becker Narvaes, of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO). “Teatro do Sentenciado opened up discussions about race inside the prison system by celebrating figures like abolitionist José do Patrocínio [1853–1905],” she explains. Narvaes’s doctoral dissertation on the group, completed in 2020 at the University of São Paulo (USP), is slated for publication this year by Hucitec.

In 1968, as Brazil’s military regime intensified political repression under Institutional Act No. 5 (AI-5), Nascimento chose to remain in the US, where he was living on a scholarship from the Fairfield Foundation. “In Oakland, Abdias was welcomed by the Black Panthers and was already seen as a major figure within Pan-Africanism—an international movement advocating for the rights and interests of Black peoples,” says Gilberto Alexandre Sobrinho, of UNICAMP’s Institute of Arts. During his postdoctoral fellowship at New York University from 2021 to 2022, with grant funding from FAPESP, Sobrinho researched Nascimento’s years in the US. He remained there until 1981, with an interlude in Nigeria between 1976 and 1977.

MASP Collection | Elisa Larkin Nascimento / Abdias Nascimento Collection / IpeafroNascimento speaks at Serra da Barriga (Alagoas), in 1983; Okê Oxóssi (1970), a painting by NascimentoMASP Collection | Elisa Larkin Nascimento / Abdias Nascimento Collection / Ipeafro

In the 1970s, Nascimento took up a teaching position at the State University of New York, in Buffalo, where he founded the Chair of African Cultures in the New World. Because he wasn’t fluent in English, he conducted his classes in Portuguese, with translators assisting his students. Alongside his academic life, Nascimento took up painting, creating images inspired by orixás—African deities—and religious traditions of Afro-Brazilian culture. “Abdias became part of the Latin American arts scene in Harlem, in upper Manhattan, and interacted with key figures of the Black Arts Movement,” says Sobrinho. “He wasn’t looking to sell his art to galleries, but to build a collective visual identity that reflected the aspirations of Black Brazilians.”

When he returned to Brazil in 1981, Nascimento founded the Afro-Brazilian Research Institute (IPEAFRO), which is now led by his widow, social scientist Elisa Larkin Nascimento. In the 1980s, he ventured into Brazilian politics. After successfully running for Congress (1983-1987) with the Democratic Labor Party (PDT), Nascimento later served as a substitute senator in the 1990s for anthropologist and politician Darcy Ribeiro (1922-1997). Following Ribeiro’s death, Nascimento held the Senate seat until 1999.

During his tenure, Nascimento proposed legislation on reparations for Brazil’s Black population. His initiatives passed through all legislative committees, though they never advanced to a full congressional vote. Before his death in Rio de Janeiro in 2011, at the age of 97, Nascimento was able to witness some of the ideas he had long championed take shape through the efforts of other lawmakers. “What we now call reparative or affirmative action was already being advocated for by the Black Experimental Theater back then,” notes Sobrinho. “They even pushed for something resembling today’s racial quotas.”

The story above was published with the title “A stage for struggle” in issue in issue 349 of march/2025.

Project

Afroperspectivism and artistic creation: Struggle, thought and images in Abdias Nascimento (nº 19/22573-9); Grant Mechanism Research Fellowship Abroad; Principal Investigator Gilberto Alexandre Sobrinho (UNICAMP); Investment R$83,266.96.

Scientific articles

SOBRINHO, G. A. O legado do Teatro Experimental do Negro (TEN): Lições de estética, política e comunicação. Conceição/Conception. 2023.

SOBRINHO, G. A. Abdias Nascimento no século XXI e o trânsito de suas obras e ideias nos circuitos da diversidade. Brasiliana: Journal for Brazilian Studies. 2024.

SILVA, M. A. M. O Teatro Experimental do Negro de São Paulo, 1945–66. Novos Estudos Cebrap. 2022.