In 1969, at the age of 19, José Augusto Chinellato was a first-year physics student at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), living in a boarding house on Rua Culto à Ciência in the center of the city. One day, he decided to apply for a job in the laboratory located in the basement of the building opposite — now the Technical College of Campinas (COTUCA) — which he knew was headed by none other than the physicist César Lattes (1924–2005). “I went in and asked to work on something,” recalls Chinellato. “I was given the task of looking for traces of collisions of cosmic rays [particles from space] recorded on photographic plates.” Cosmic rays were Lattes’s main research topic (see report on page 56). A partnership blossomed. In the following years, Lattes acted as his advisor during his master’s degree and PhD at the university’s Gleb Wataghin Institute of Physics (IFGW).

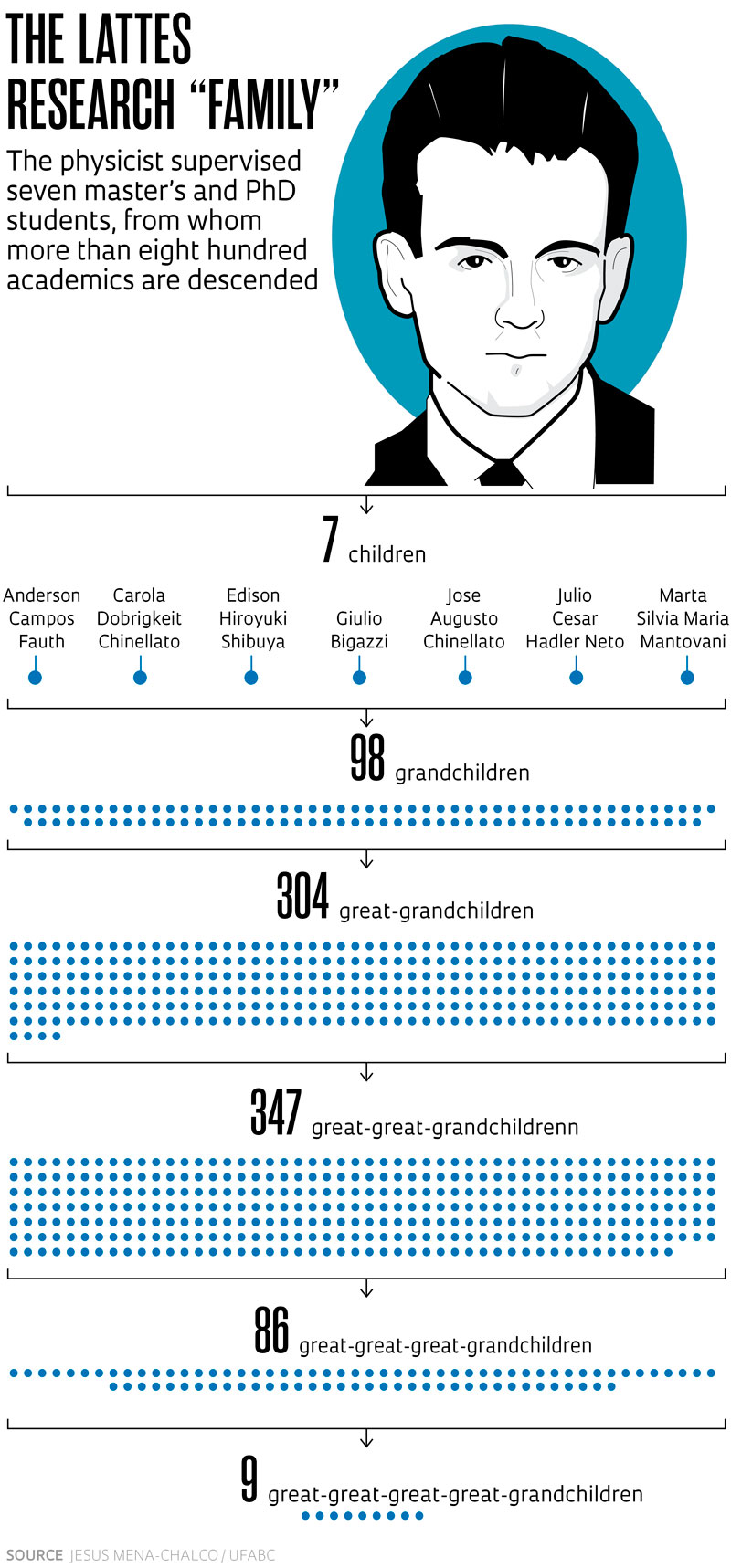

Chinellato is one of the seven academic “children” of Lattes — people who were mentored by him in graduate school — according to a recent study. The survey data was used to draw graphs that show the direct and indirect links between the physicist and different generations of researchers. Lattes is thus considered the “father” of the master’s and PhD students he supervised, who are classified as his “children.” Researchers supervised by these “children” are the academic “grandchildren” of Lattes, and so on. An analysis based on data from March 2024, carried out by computer scientist Jesús Mena-Chalco of the Federal University of ABC (UFABC) at the request of Pesquisa FAPESP, identified 851 academic descendants of Lattes (see graphic).

“They are split across six generations from between 1966 and 2024, considering master’s, doctoral, and postdoctoral advisees, supervisees, and co-supervisees,” explains Mena-Chalco, who extracted the data from the Lattes Platform. Of those for which it was possible to identify the degree type, 312 were doctorates and 416 were master’s degrees. The descendants are mostly from the fields of physics (26.12%) and geosciences (18.99%). Mena-Chalco notes that this type of work has limitations. “It is possible that there are researchers who did not register their résumés on the Lattes platform or were not named by their advisors,” says the computer scientist, coordinator of Plataforma Acácia, a project that has been reconstructing the academic lineages of Brazilian researchers since 2019.

Some of the descendants followed the same line of research of their academic parents. Chinellato was hired as a professor at the Physics Institute at UNICAMP at the age of 25, on Lattes’s recommendation. Today, he works at the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina together with his wife, Carola Dobrigkeit Chinellato, another academic daughter of Lattes.

“This observatory is currently the world’s leading experiment on high-energy cosmic rays,” says UNICAMP physicist Anderson Fauth, who also works at Pierre Auger. Fauth, who has a degree in physics from the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), arrived in Campinas in 1982 to study meson particles during a master’s degree under the supervision of Lattes. He recalls his sarcastic sense of humor: “One of the first things he told me was not to be shy about asking questions.” The supervision lasted until 1985. “He had to leave due to episodes of depression. I was then supervised by Japanese researcher Kotaro Sawayanagi, also from UNICAMP.” During his PhD, supervised by physicist Armando Turtelli Junior, Fauth worked on the development of cosmic ray detectors and was later head of the Lepton Laboratory at the Department of Cosmic Rays and Chronology, founded by Lattes.

One of Lattes’s 98 academic grandchildren, physicist Sérgio Roberto de Paulo of the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT), studies physics applied to the environment and remembers seeing Lattes around the IFGW after he retired. “He imprinted principles on our group that remain to this day, even though I work on a different line of research, such as: not following fads, having ambitious scientific goals, and never sweeping unexpected results under the carpet. They need to be analyzed,” says de Paulo, who was supervised by UNICAMP physicist Julio Cesar Hadler Neto during his PhD, which he defended in 1991.

Luiz Vitor de Souza Filho, a researcher from the São Carlos Institute of Physics at the University of São Paulo (IFSC-USP) who is another of Lattes’s academic grandsons, works in the field of particle astrophysics. For him, the field is heir to the first lines of research on cosmic rays led by the great physicist. “Without abandoning the study of particles, more time and resources are now spent attempting to understand the origin of the energy of cosmic rays,” says the physicist, who was supervised by Carola Chinellato at UNICAMP from undergraduate to doctorate, which he completed in 2004. During this time, he crossed paths with Lattes just once. “Even so, he was omnipresent. Not a day went by without hearing his name. Some stories were exciting and motivating, others not so much,” recalls Souza Filho. He is currently chairman of the international scientific committee overseeing works on the Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA), which will be the largest gamma-ray astronomical observatory in the world.

Souza Filho supervised astrophysicist Rita de Cássia dos Anjos during her PhD at IFSC-USP, for which she studied the propagation of high-energy cosmic ray particles, graduating in 2014. Later that year, she became a professor at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), Palotina campus, where she collaborates as a member of the Pierre Auger and CTA observatories. At UFPR, she created a high-energy physics research group. As a faithful academic great-granddaughter of Lattes, she retains the initiative to seek international collaborations and research funding. “It is important to expand these studies beyond the Rio-São Paulo axis,” says Anjos, who was one of the laureates of the L’Oréal-Unesco-ABC Program for Women in Science in 2020 and was awarded the 1st Anselmo Salles Paschoa Prize by the Brazilian Physics Society (SBF) in 2023.

Republish