When propagating through a material, a laser beam of significant intensity slightly modifies the density of the physical medium and generates tiny vibrations. These acoustic oscillations distort the material and can cause alterations in the original characteristics of the light beam. Two recent scientific articles to which Brazilian physicists contributed presented experimental progress in controlling the interactions between light waves (photons) and acoustic or mechanical waves (phonons) within a physical medium—the phenomenon briefly described above.

“The papers describe advances that could help in the development of devices for quantum communication systems,” says Gustavo Wiederhecker of the Gleb Wataghin Physics Institute at the University of Campinas (IFGW-UNICAMP). Wiederhecker coauthored one of the articles and heads FAPESP’s QuTIa Quantum Technologies Program, under which the two studies were carried out.

The first article, published in Nature Communications on March 15, presents a silicon crystal designed to very quickly dissipate heat and to increase efficiency when processing information based on qubits (quantum bits). The second, published in Physical Review Letters on March 21, reported on a new strategy for manipulating the polarization of light, meaning the (vertical or horizontal) plane on which its electromagnetic waves vibrate. This advance could be useful for producing thinner, purer laser beams, which could, theoretically, increase data transmission capacity in optical fibers.

Both studies were conducted by physicists from UNICAMP in partnership with American universities. With different approaches, both studies have contributed to the development of optical devices capable of performing so-called quantum transduction through acoustic oscillations. The process consists of using mechanical vibrations to convert quantum information between two forms of energy, from one wavelength of the electromagnetic spectrum to another. To create a quantum network, qubits encoded in microwave frequencies need to be converted into quantum bits that work with visible light, without significant loss of information.

This is the focal point of the Nature Communications article, which suggests that quantum transduction can be performed using a silicon crystal with which light can interact along a plane in two dimensions. Until now, transducers have always been crystals, whose structure allows for interactions with light in one dimension, only in a given direction. The disadvantage of these one-dimensional crystals is their propensity for residual heating. The material absorbs some of the light energy, making the transduction process less efficient. “Our crystal was designed to ‘talk’ to the superconducting qubits and to dissipate heat very quickly,” explains IFGW-UNICAMP’s Thiago Alegre. He wrote the paper together with André Primo, who completed his PhD under Alegre’s supervision in 2024, and with colleagues from Stanford University, USA.

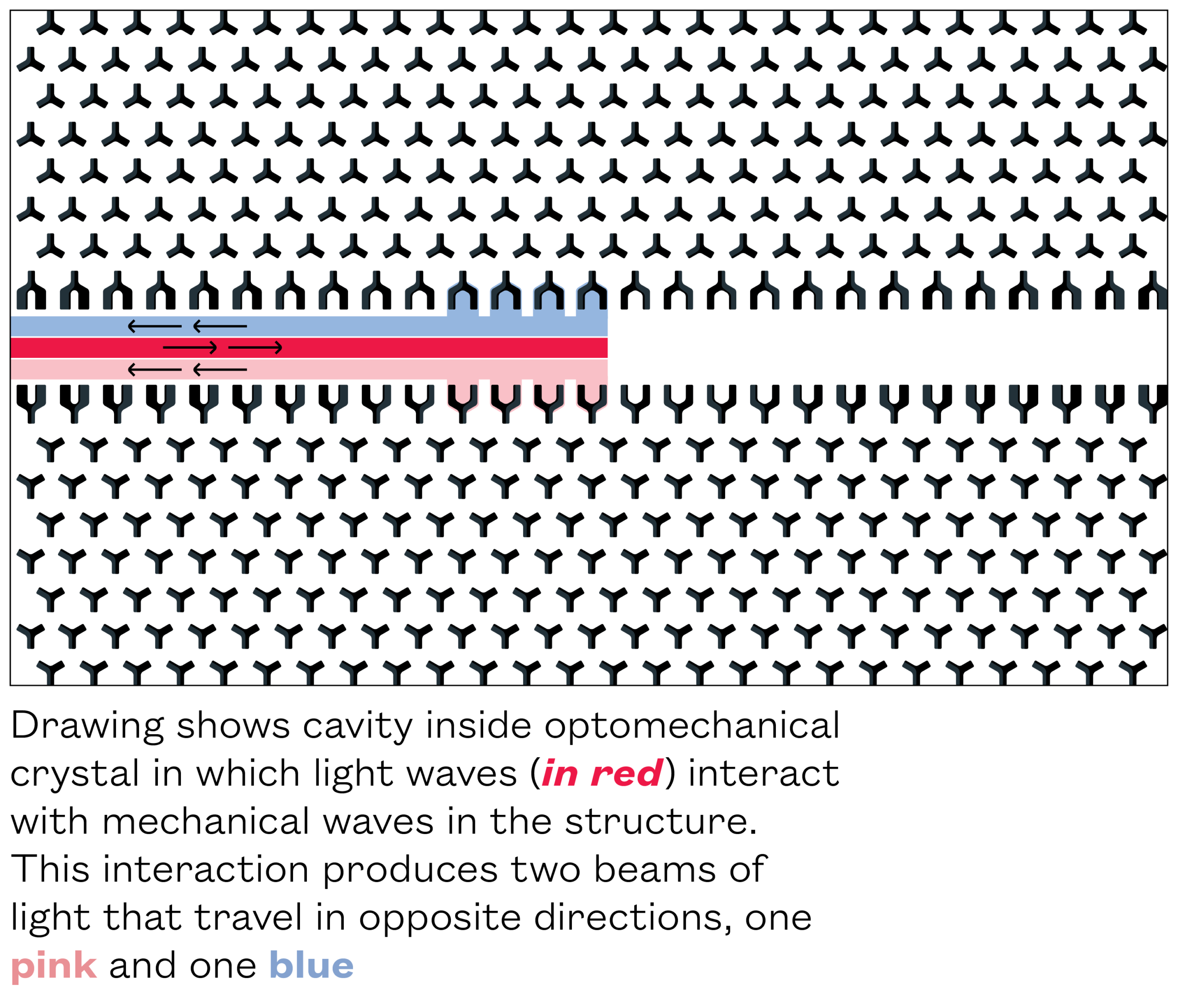

To curb the temperature increase, the researchers designed a two-dimensional optomechanical crystal with structures they called “boomerangs” and “daggers.” The boomerangs, which are more external, function as shields against interactions between the crystal and the environment, preventing mechanical disturbance. The more internal dagger structures serve to trap the light inserted into the crystal with an optical fiber. In addition to confining the photons, the daggers also vibrate, generating acoustic waves. The phonons arising from this vibration interact with the photons between the daggers and couple to them. Due to this quantum coupling, any change in the state of the photons causes an almost instantaneous change in the phonons, and vice versa. The result is that within this device, it is possible to convert information contained in light into acoustic vibrations.

To transmit information between quantum processors usually requires superconducting materials that operate at microwave frequencies and at extremely cold temperatures, close to absolute zero (-273.15 degrees Celsius). A microwave transmission line between these devices would have to operate at similar temperatures, since at these frequencies, quantum information becomes disorganized at higher temperatures. In practice, the cooling required to build longer quantum networks of more than a few meters hits a thermal barrier.

The geometry of the crystal proposed by UNICAMP and its partners overcomes the problem of residual heating, but it still needs to be refined so that it can handle converting quantum information from one form of energy to another. The team has not yet been able to fully control the acoustic vibrations of the crystal during the process of converting data from microwave frequencies to visible light frequencies. If this goal can be achieved, it will be possible to transmit quantum data via lasers over extensive fiber optic networks. “Fibers are excellent thermal insulators and information carried by light is not disturbed by temperature variations,” says Primo.

Anderson Gomes, a physicist from the Federal University of Pernambuco who did not participate in the study, says the research is highly original. “It extends the frontier of knowledge in optomechanics,” he says. “It is the first step towards demonstrating transduction with a two-dimensional silicon crystal.”

The second article addresses a phenomenon known as Brillouin scattering, a process that occurs when the properties of a light shining on a medium are altered due to the influence of the material’s acoustic vibrations. The result of this interaction between photons and phonons is that the scattered light can have a different frequency (color) than the incident light. In the field of communications, the manipulation of this type of scattering, proposed in 1922 by the French physicist Léon Brillouin (1889–1969), is currently used to measure temperature and pressure in optical fibers.

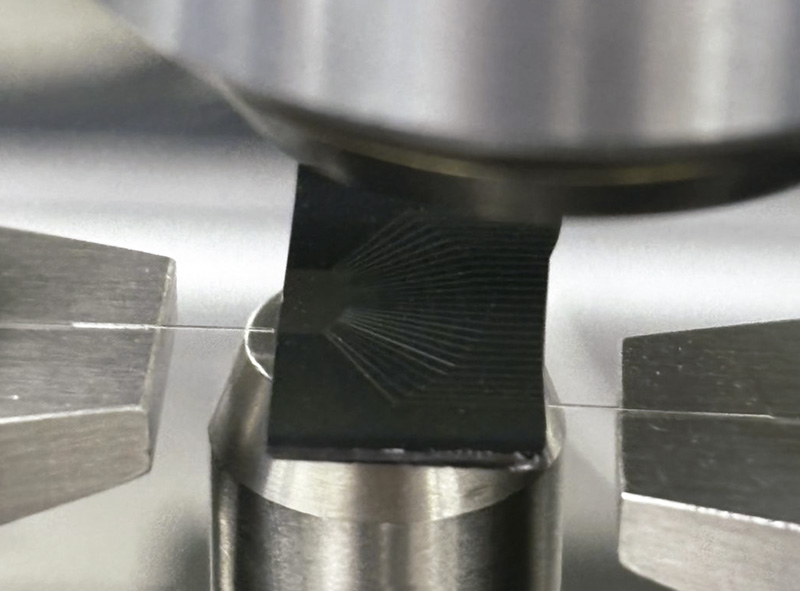

Thiago Alegre / UNICAMPImage of a waveguide created at UNICAMP (black rectangle), attached to two optical fibersThiago Alegre / UNICAMP

In the article published in Physical Review Letters, physicists directed a laser beam into lithium niobate (LiNbO₃) waveguides in an effort to change the light’s polarization (the plane on which its electromagnetic waves vibrate). This type of alteration can produce purer, finer lasers, which tend to be more efficient at transmitting information. Waveguides are structures that confine and direct the propagation of electromagnetic waves (usually lasers) or mechanical vibrations.

Lithium niobate, a material often used in telecommunications, has a microscopic hexagonal structure like a honeycomb. One of its properties is that it is anisotropic, meaning that changing the orientation of its structure modifies the way it interacts with light. Waveguides are typically made from isotropic materials such as silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), which interact with electromagnetic radiation in the same way regardless of the orientation of their structures.

In addition to being anisotropic, lithium niobate was chosen for the experiment because of another desirable characteristic: it is piezoelectric, which means it produces electrical charges when it vibrates or is subject to mechanical stress. Experiments carried out at the IFGW’s Integrated Photonics Laboratory indicate that changing the incline of a LiNbO₃ waveguide alters the intensity of light scattering. The electromagnetic frequency of the scattered waves also differs depending on the angle.

In lithium niobate waveguides, light interacting with vibrations is scattered in cross-polarization. If the initial laser beam is horizontal, the light reflected by the phonons of the physical medium is vertically polarized and vice versa. “This way of manipulating the information transmitted by light could be useful for manufacturing waveguides that function as polarization converters,” points out the study’s lead author, physicist Caique Rodrigues, who completed his PhD at UNICAMP in early 2025, supervised by Wiederhecker. In addition to Rodrigues, the paper was coauthored by Wiederhecker, Alegre, and four other researchers from the UNICAMP optics group, as well as colleagues from Harvard University, USA.

Cleber Mendonça, a physicist from the São Carlos Physics Institute at the University of São Paulo (IFSC-USP) who did not participate in the study, highlights that the results reinforce the possibility that the polarization of light can be manipulated with something similar to an optical key. “It could thus be possible to select the light polarization that would or would not propagate inside optical fibers,” he says.

The story above was published with the title “The light of sound” in issue 351 of May/2025.

Projects

1. Nonlinear nanophotonic circuits: Fundamental blocks for optical frequency synthesis, filtering, and signal processing (n° 18/15577-5); Grant Mechanism Research Grant – Young Investigator Award – Phase 2; Principal Investigator Gustavo Silva Wiederhecker (UNICAMP); Investment R$2,638,358.71.

2. Optomechanical cavities for strong coupling with single photons (n° 18/15580-6); Grant Mechanism Research Grant – Young Investigator Award – Phase 2; Principal Investigator Thiago Pedro Mayer Alegre (UNICAMP); Investment R$3,035,457.34.

3. Integrated photonic devices (n° 18/25339-4); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Newton Cesário Frateschi (UNICAMP); Investment R$8,503,478.05.

Scientific articles

RODRIGUES. C. C. et al. Cross-polarized stimulated brillouin scattering in lithium niobate waveguides. Physical Review Letters. Mar. 21, 2025.

MAYOR. F. M. et al. High photon-phonon pair generation rate in a two-dimensional optomechanical crystal. Nature Communications. Mar. 15, 2025.

Republish