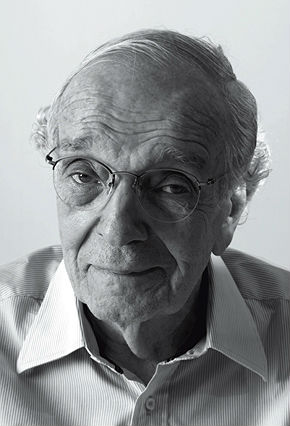

Léo RamosAlberto Dines, one of the most respected and polemic Brazilian journalists, turned 80 on Carnival Sunday, February 19. He celebrated the date by having a quiet lunch with his wife, Norma Couri, who is also a journalist. Still, such a discreet event for a master of several generations of media professionals, who has been active in the field since the early 1950s, could only be due to the dispersion of people that sweeps over the country during Carnival. Once this period, drowsy or fey, depending on one’s viewpoint, was over and done with, the tributes to Dines multiplied. They ranged from parties to intense debates, including a seminar organized by FAPESP on March 22, “The scientific knowledge of journalism in Brazil: the contribution of Alberto Dines.”

Léo RamosAlberto Dines, one of the most respected and polemic Brazilian journalists, turned 80 on Carnival Sunday, February 19. He celebrated the date by having a quiet lunch with his wife, Norma Couri, who is also a journalist. Still, such a discreet event for a master of several generations of media professionals, who has been active in the field since the early 1950s, could only be due to the dispersion of people that sweeps over the country during Carnival. Once this period, drowsy or fey, depending on one’s viewpoint, was over and done with, the tributes to Dines multiplied. They ranged from parties to intense debates, including a seminar organized by FAPESP on March 22, “The scientific knowledge of journalism in Brazil: the contribution of Alberto Dines.”

And what a contribution! From Cadernos de Jornalismo e Comunicação” [Journalism and Communication Supplements] published by the Jornal do Brasil daily in the 1960s and 1970s, to the classic book, “O papel do jornal” [The paper/role of the newspaper], published in 1974, from the polished analysis of the second half of the 1970s on Brazilian communication vehicles in his column “Jornal dos jornais” [Newspaper of newspapers] in the daily Folha de S. Paulo, to the contemporary “Observatório da Imprensa” [Observation of the press] started in the late1990’s, Dines has both produced and rigorously reflected about Brazilian journalism, almost uninterruptedly, for six decades. And all of this in parallel with his experience in organizing copy writing, on par with his capacity to invent communication vehicles. And, of course, during brief intervals, to write splendid books such as “Morte no paraíso” [Death in paradise] in 1981, and “Vínculos do fogo” [Links of fire] in 1992, biographies of Stefan Zweig and of Antônio José da Silva, the Jew, respectively.

All these achievements, which show the pioneering spirit of Dines, his inclination to create new approaches that cast light upon the exercise of journalism and his investigative journalistic ability to recreate the obscure pathways of famous people, were the subject of talks given during the seminar organized by FAPESP (see www.agencia.fapesp.br). Dines speaks a little about all of this in the following interview with Pesquisa FAPESP.

Our objective here is to explore your contribution to the theoretical knowledge and practical aspects of journalism. Let’s start with the Cadernos de Jornalismo [Journalism Supplements] that you organized during your time at Jornal do Brasil.

Yes, it was in 1965. At that time, I had already been in professional journalism for 10 years and had had 2 years of academic experience, because I had started to lecture at PUC in 1963. I had a focus of sorts, not a theoretical approach, but a thinking one. When PUC invited me, I saw that I had experience in several journalistic activities and I accepted – I had worked in morning and evening papers, two different styles of journalism at that time, in radio and cinema, which was a dream, and had ventured into television a little. So, as you would say today, I had experience in several media platforms, and I thought that I should systematize all of this. Intuitively I concluded that the discipline that I would like to teach was comparative journalism .

So you invented the discipline of comparative journalism in Brazil in 1963.

As far as I knew, it didn’t exist. The idea came from comparative law. From a comparison, you can establish differences and paradigms. The fact is that the Jornal dos Jornais experience was, in a way, a consequence of this first path. However, between PUC and the launch of the first Caderno de Jornalismo [Journalism Supplement], there was an experience that I see as an epiphany in my professional career, in all senses. In September of 1964, I went to do a three month complementary course at Columbia University, in New York, connected with an organization that doesn’t exist anymore, the World Press Institute. Columbia invited newspaper editors from each continent and they put together a program with a special course. Mine was for the editors of Latin-American newspapers.

Fantastic!

Marvelous! It was my first course in a university. With good professors and great professionals. I still have all the books and also my notes, which I took thinking about the Jornal do Brasil. Besides the course itself and the resulting friendships, there was an interesting thing where we could choose, in groups of three, newspapers where we could make an extended visit. So I got together with an Argentinean from Cordoba, Jorge Remonda, whose family was the owner of a very good newspaper there, La Voz del Interior [The voice of the –hinterland], and Uribe, whose first name I can’t remember now, was a member of one of the important Colombian families, and was connected with what is now the most important newspaper in Bogotá. We formed a group – there was money for travel – and we choose to go to the Pacific coast. We visited the Los Angeles Times. Afterwards we went by car to Seattle and then by plane to New York and there we split up. I wanted to see the New York Times; obviously for me, a very important newspaper, and then the New York Herald Tribune. At that time, it was independent and fascinating. A newspaper-magazine. I pursued this a lot, because my early career experience was in a magazine. First Visão and then Manchete, Fatos & Fotos… While in newspapers, I worked for Última Hora [Breaking News], Diário da Noite [Night Paper], etc. I was thinking in a symbiotic way about bringing together newspapers and magazines. In other words, a well written newspaper, well finished, hence the fascination of the Herald Tribune, including its modus faciendi, meaning the newspaper put together during a single meeting throughout the day by a team of great text, photo and design journalists.

And you returned from the United States to join the Jornal do Brasil inspired as much by the New York Times as by the Herald.

In the New York Times, a classic newspaper, which I would describe as orthodox, I saw something that really made an impression on me: in the old editing building still near Broadway on 43 rd Street, there was an enormous broadside on the wall produced by the journalists called Winners and Sinners. It commented on a subject, using arguments, jokes and making fun, everything. I wanted to do something like that. It couldn’t be a posted broadside, which I something really like. As it happens, when I was a militant in the Zionist socialist movement I did a course on broadsides. However, in the old Journal do Brasil this wouldn’t do, the writing was split up into rooms, so then I thought about something similar but with another format.

You joined Jornal do Brasil in 1962. After PUC and the United States, you returned to the newspaper with new powers and a very broad view.

I joined JB on the 8th of January of 1962. I had no defined position. My name only began to appear in the credits after 1964. They said that I needed to manage the work. I agreed and suggested that I could be the managing editor because I had organized the editing in publishers, which was unusual. If I have any merit regarding JB, it was the organization of the editing of the newspaper. I think I inherited a certain gift for organization from my father. While still in Russia before the First World War, he had taken a secretarial course, that was basically small scale management . Then I learnt from him seeing him work. From the early days, he established t a connection with the major international Jewish organizations of support for immigration. There were great philanthropic Jews and the twentieth century was underscored by large population migrations due to wars, pogroms, and later inflation, after the 1920s…these organizations needed people who could speak several languages and who had organizational skills. It was necessary to get the Jews out of small towns where they lived on charity and provide them with a manual occupation that might enable them to transform themselves. I didn’t really understand the purpose of my father’s work. However, there were always files on his desk that were very well organized and this I assimilated.

You spoke about your father already in Brazil.

Yes, there was a period when he worked in commerce in Curitiba; soon after he went to Rio, was employed and worked for 25 years in a large organization that was a forerunner of the Albert Einstein hospital. The fact of the matter is that I think I was a good editor who was concerned about creating clearly defined sections.

Which sections did you have in those early days? Political, general subjects…

Politics at that time was practically limited to Brasília. In Rio we had a collaborator, Heráclito Sales, who was had column, and the city reports that covered the House of Representatives. We created an economics section, which didn’t exist before. The newspapers reproduced what they received from the New York, Chicago and Rio de Janeiro stock exchanges, and also what came from the commodities exchange. When there was a government decision, it would be on the Brasília page. We also started to be concerned with commentaries. In sum, we started to plan the newspaper.

Was this first meeting held in the morning?

No, in the afternoon. The newspapers started working very late because everyone had two jobs, me included. In the morning I worked at Manchete, at that time on Fatos & Fotos [facts and photos], and after lunch I would go to Jornal do Brasil. For several years, I had two jobs, as did all the journalists. After this time, we pushed for, and it happened, a full time job with a 7 hour-day for reporters, and not just 5 hours as previously. After the establishment of the different sections, this being a new work methodology, we started holding two meetings per day. Actually, one of the first areas I also created was research. The newspaper didn’t even file any of its photographs. There were no dictionaries. I proposed that we start building a basic library, with reference books and that we file the negatives. We started buying books, to build up a database (there was no internet), with everything in files and so, we created a research department. With this, the reporter could consult the information in the research department before he prepared his material. This became standard practice. In 1965, I decided to turn this department a producer of content, as we would say today.

And this was in fact, an innovation for Brazilian journalism.

Yes, also because we employed an extraordinary team of journalists: Fernando Gabeira, Murilo Felisberto, Moacyr Japiassu, and later Raul Ryff, who had been the secretary of former President Jânio Quadros. To sum it up, great journalists, young and older, to compose coherent and complete material, used to support the facts of the day. And we supplied services – at that time agencies that prepared and supplied background information for newspapers already existed. The JB authorized this expense because it would improve the quality of newspapers content, as we were very concerned about the quality of information. And when the Globo TV network started in 1965, I prepared a memorandum of about 10 pages for all the editors and managers, informing them that from then on, we would have a real competitor. Because the Tupi TV network, a pioneering concern, was a confusion of associates. When Globo came on the air with Time-Life as a partner, I thought “now we are really going to have a competitor.” I installed TV in the editing offices and we started to work keeping our eyes on the enemy.

Let’s get back to the Cadernos de Jornalismo [Journalism Supplements]

On returning from the United States, the question was how to do something that was similar to their broadsides. The management of JB wasn’t very interested in my dream. They didn’t rule it out, however, saying “Dines, invent something and do it.” I started to pester several people about this, and Gabeira, who managed the research department, a think tank, let’s say, was the first. He and Murilo Felisberto, both from the state of Minas Gerais, adored talking about journalism. In fact, in Gabriel García Márquez’s book on speeches, a brilliant work that has been published already Portuguese (Eu não vim fazer um discurso, Record, 2011), he tells us how, in his time, t people worked like crazy on the editing and then in the early morning, go to a simple bar or to a restaurant to talk about the newspaper. Here we also had our specialists in this. To sum it up, I spoke with Gabeira, who as research editor, would be in charge of this. The JB company had a small printing works to print forms and reports and I managed, together with the manager of the printing works, to print a short run of the supplements, with a slightly better quality paper, and a colored cover printed on coated paper. It was for in-house circulation, distributed to advertising agencies and to friends. Later on, we made an agreement with a chain of book stores called Entrelivros that also started to sell them. All of this against the wishes of the senior management. In the end, the undertaking was successful and we produced I don’t know how many issues, about four or five a year. It should have been every two months but we never quite managed to achieve this. I encouraged Oldemário Touguinhó [1934-2003] who was a straightforward person and a first class journalist, a sports editor, to write for the notes. He was such a true journalist that when he finished his column, he’d go and have his dinner and then a beer , but he couldn’t go to bed without passing by the newspaper to see it being printed, and he would often find a mistake. He was an incredible character who died prematurely. He would cover the World Cup and if there was anything different, like what happened in Mexico in 1970, with the student revolts, he’d send material covering it. And afterwards he reported this in the notes. That was what we wanted.

While you led this process, the newspaper was actually transformed into a reference, into a model for the whole country.

The title, Jornal do Brasil, helped a lot in this sense. Rio de Janeiro, apart from its having been the country’s capital, was a city with a national vocation. The character of the Rio inhabitant overflowed into the rest of Brazil. It was well assimilated by São Paulo, more circumspect, by the Minas Gerais, less vocal, by the Northeast, and in the end, the newspaper managed to achieve this sort of synthesis. Another thing that was very important was the development of a fabulous network of correspondents and large branches. The JB network of branches was an investment the yielded good returns. It brought a lot of political influence and financial returns for the newspaper, because the publishing team of each branch was very good.

However, apart from this, Dines, I would say that the influence of JB was due also to the internships of the professionals in other places in Rio.

Indeed, we did encourage this a lot and we did it because I had realized what it had been like to visit the New York Times for example. We had to have the function of a school. Something that I thought was very important at that time and that wasn’t much commented on was that we created a distribution agency for journalistic material, the AJB (Agência Jornal do Brasil). The only domestic predecessor of this service was Agência Meridional, of the journalist Assis Chateaubriand. As I had concerns that one might call social, the income from each article published in another newspaper was divided by three: the reporter, the agency and the newspaper.

You established a copyright model.

It was a cooperative model that was linked to my past in the Zionist socialist militant movement. And with these newspapers we collaborated in all ways. Always, when I was able, I would give a talk to the editorial staff. So, if the newspaper per se was a model, as the graphic revolution of JB was the most influential that there had been in the country, we developed an excellent system of dissemination. The reforms, under the leadership of Odylo Costa Filho , took place in 1956. Brito wanted to neutralize him and on the day he took over, he said to me “I want another newspaper.” I replied that I wasn’t going to that, on the contrary, all that was needed was to fix a few things.

Brito was the …

Manuel Francisco do Nascimento Brito, son in law of the countess Pereira Carneiro. The countess had only one daughter called Leda from her first marriage. She later married count Pereira Carneiro, and they had no children. Then Leda married a young, handsome boy from Rio whose dream of becoming a diplomat didn’t materialize; however, he accomplished important things. As an entrepreneur, for example, he funded the renovation of the JB radio station, and for this he invited excellent people, in particular Reynaldo Jardim, who was an extraordinary character. Unfortunately, he died last year [on Feb. 1, 2011]. He was an excellent poet, a real idealist and he was always a permanent creator. He was the one who came up with the Caderno B [B Supplement] section.

We have the impression that you were especially fond of the B during your work as chief editor.

That was true. B was created during Odylo’s renovation and his intention was to use the leftovers on the next day. Because the newspaper photographed a lot, there were a lot of good pictures that that could not be used in the normal “hot” edition. For example, that famous photograph of Jânio Quadros with his feet pointing inward, taken by Erno Schneider who was a great photographer from Rio Grande do Sul state.

Which Pesquisa FAPESP, incidentally, republished exactly one year ago in issue nº 182.

The photograph came out in the Caderno B [B Supplement] section two days after the event [the meeting of presidents Jânio Quadros and Arturo Frondizi, of Argentina, on the bridge at Uruguaiana, on April 21, 1961 . There was some noise behind the Brazilian president while he walked to the meeting and according to Schneider, this made half turn to look back]. In general, it was just this, re-using hot news. And B went out four days a week, whereas the newspaper didn’t circulate on Mondays, which was the case of all the morning papers at that time. I extended the circulation of B to the other days, Saturday being the literary B day, with more literary material and illustrations. Little by little, I transformed it from a news recycling section and moving it toward its own production, great interviews, etc. This turned JB into a newspaper with ideas. We had a collection of fantastic critics and we prepared a famous table showing their votes. This opened up the newspaper for debates. We had theater critics, art critics, etc. The newspaper covered culture and it shined in this area.

You stayed with JB until 1973 and then faced dramatic problems after the AI-5 decree. And then, Dines, regarding your intellectual journalistic production, you waited during 1974 and 1975 for something to happen. Then came the Folha de São Paulo and the Newspaper of newspapers.

When I was sacked from JB, the doors were really closed. People that had invited me six months before said to me “I can’t employ you any longer; the government doesn’t want you.” Armando Nogueira who was a great personal friend said to me, “I can’t employ you now. However, if you travel, we´ll see what we can do afterwards.” The Editora Abril publishing house had offered me a top management position in São Paulo, but they couldn’t maintain the offer. Roberto Civita was my friend and came to me and said, “Spend some time abroad at some university,” and added, “Write a book.” I told him that I was already writing a book “O papel do jornal” [The role of the newspaper] and that going abroad wouldn’t be a bad idea. Soon after came the invitation from Columbia University. I´m sure that it was he who articulated this, even though he denied it,, because this invitation appeared from the Tinker Institute and I evidently accepted it. I stayed there in 1974 and 1975.

Was it during this period that this book was published?

No, it came out in March or April of 1974. I started to write it two weeks after being fired. In the last issue of the supplements, that was not published, there was a large article of mine, under the title “A crise do papel e o papel do jornal” [The paper crisis and the role of newspapers].” Unfortunately, I didn’t keep it, but I wrote the book as a result of it, since the paper crisis was real, the newspapers wanted to reduce the number of pages, wanted to cut down services, they had the same suicidal instincts they display today. I have already witnessed this business of the press wanting to commit suicide when they discover they have a competitor. At that time, the competitor was television.

Today, is the suicide impulse due to the internet?

Yes, obviously. If you get hold of the book, whose text is practically the same as the article, what I say there is that “we need better newspapers and not worse ones. Give us newspapers that can even be more expensive,” as the intelligent reader will be willing to pay a little more for the paper, which was already expensive because of the oil crisis, in order to have a good newspaper.

The book was a success in the middle of the silence of Brazil’s society at that time…

It was. There weren’t many books on journalism; Danton Jobim had published Espírito do jornalismo (The spirit of journalism) in 1960, but there weren’t many more books.

Our classic study was still the História da imprensa no Brasil [The history of the press in Brazil], by Nelson Werneck Sodré, from 1966.

Just that. There were some books on journalism in general that had been translated and their publication was financed by the American embassy. Then, when I saw that there was a ring fence against my staying in the profession, I thought about leaving at least a description of my ideas, of my experiences and of what Jornal do Brasil did at various times. It was with this spirit that I wrote “O papel do jornal” [The role of the newspaper].

How did your second stay in New York affect what you did afterwards?

The influence upon why due to living there was extraordinary. Because it was 1974, post Watergate, and the press was discussing the situation intensely. All the concepts of media watching and media criticism were found in the day to day discussions. There was the case of a public prosecutor who monitored the Watergate case; he conducted part of the investigation and then when this was finished sold a series of articles to a newspaper. From then on, a discussion arose about what came to be known as checkbook journalism, in which the statement by someone is paid for, even if their work was public. This became an ethical debate, and for me this discussion was a positive shock [see this link, for example].

What did you work on during this time?

I lived on 119th Street, in a hotel that Columbia had for academic staff near the campus. I had tasks to carry out, seminars, but it was always understood that I had nothing to teach there and that I was there to learn. For the students that were interested, I could describe what the press was like in Latin America, especially the relations between the government and the press. So much so that the theme of the two conferences that I had to do, one each in each school term, was the relations between the government and the press in Brazil. This was where I immersed myself in the history of the press. I hadn’t taken Werneck’s book and the Columbia library didn’t have it, so I asked Otto Lara to send it to me. The students were journalists and students from the school of journalism. It was a graduate and highly intensive. In the meeting with the professors, I noted everything down; I was an extraordinary apprentice.

And from that time came again the desire to produce a broadside. The United States appears to have stimulated this.

It was more or less that. I think it was in March 1975; Cláudio Abramo went to New York and had lunch with me. He already had the authorization from Octavio Frias to implement changes. He said to me “I think you have never read the Folha,” which was true. Nobody read the Folha. It was a tremendously bad newspaper. He told me that they wanted to publish a newspaper with good content and he wanted me to promise that the Folha would be the first vehicle that I would contact when I returned to Brazil. I did just that. Frias proposed that I manage a branch and write a political article. I had written very little at Jornal do Brasil. Whenever I had an idea, I would pass it on to the writing crowd. I think that this position is like that of a conductor. However, Frias lit up in me the wish to write and we made use of this to write together an opinion column, which newspaper lacked. Ruy Lopes, from Brasília, at the top of the page, with me in the middle and at the bottom, the columnists took turns. Cláudio Abramo, who was the expert on design did that; he made some suggestions and the thing worked. Also, I spoke with Frias for him to pay me nothing more than what we had agree on, I wanted to write in the second section on Mondays, the worst issue of the week. He asked why and I explained that I wanted to comment on the work of the newspapers and other media. He said that I would only make enemies.

He was right!

Obviously! I even made some at Folha. Frias and Cláudio worked very closely together and they were the ones that decided to publish the first column that I sent for page six of the first section, and on Sunday. Today it is the ombudsman slot.

From then on, you got the times of the slow, gradual and safe détente, the watchword of the Geisel administration.

My first article in the Jornal dos jornais was “A distensão é para todos” [Détente is for everyone] and I really made some powerful enemies: Elio Gaspari and Veja and, later, in the Folha itself, where I worked until 1980, when I was sacked by telephone by Boris Casoy who was the editing director. I had written an article formally accusing Paulo Maluf of being the person responsible for the repression of the ABC strike. The article wasn’t published. The next day, I wrote another one on the same subject. This too wasn’t published. Then I published one of these articles in the O Pasquim newspaper, which I was helping during that difficult phase. I had suggested to Jaguar and Ziraldo to do a page called “Jornal da cesta” (Rubbish bin newspaper). This page had a small phrase attributed to Shakespeare: “The most important thing in the history of journalism is not what comes out in the newspapers but what ends up in the rubbish bin.” I published one of the rejected articles with the page number that it would have had in the Folha. Boris said that he felt attacked and he fired me. A short while ago I had a meeting with Cremilda Medina and I listed all of the dismissals and censures that I suffered. I even calculated the statistics.

How many were there?

Up until 2008 or 2009, about one major dismissal or aggression a year, if I am not mistaken. The first was the work of Chateaubriand. He fired me in 1960 at the time of the Brazilian democracy, when I was the editor of Diário da Noite. I was very satisfied with my performance, so much so that I went to London to spend a few days at the Daily Mirror, a newspaper whose style I liked a lot. He still fired me. Why? Because in January of 1961, the Santa Maria, a well known Portuguese passenger ship, was hijacked as an act of protest against the Salazar dictatorship. Chateaubriand decreed that the Diários Associados (Associated Dailies company) would not publish a single line about this incident. He was very close to Salazar. And I disobeyed him. I said “I can’t.” I had got hold of pictures taken inside the Santa Maria, and a tabloid lives off these sorts of photographs. We printed them and I was fired on the next day. Not by him directly, as he was already quadriplegic. The person who fired me, very elegantly and even kindly, was João Calmon. his right hand man. Late, he became a senator. He said “Oh, Dines, the old man didn’t like it, you struck deep,” and he added “but I know that you have already done something for Bloch and will easily find another job.” It was true. A week before, through a relation by marriage, Adolpho Bloch had asked me for help. He had launched the first issue of Fatos & Fotos, totally dedicated to Juscelino Kubitschek, who had passed the presidential sash to Jânio Quadros, and he didn’t know how to follow up with the second edition. The fact was that Adolpho had asked me to sort out at least number two and I had tried to put together that news magazine, in black and white, and to do it in just one run. It had no cover; or, rather, the cover was made from the same paper used inside. Black and white, beautiful! Black rotogravure with all the printing possibilities that I couldn’t use on Diário da Noite because of equipment limitations. I took along the people who worked with me and we produced a beautiful magazine, which many people worked on over time: Paulo Henrique Amorim, Itamar de Freitas, a fine young crowd.

After leaving Folha, what did you do?

I took my money and invested it; it was a good time for the stock market. I decided that I would fulfill a dream with which I was already involved: a biography of Stefan Zweig. It was in 1980 and the book had to come out in 1981, the centennial of his birth. I immersed myself in this; the only exception I made was for the O Pasquim newspaper.

I would like you to talk a little about your going to Portugal and lastly, the construction of new instruments to reflect on journalism, namely, Labjor and the Observatório da Imprensa.

I went to Editora Abril, and as editorial Vice-director, and had, at the same time, a very good period and a very bad one. Why? Because of the mafia spirit that has always been present in the Veja editorial department. It was closed, and didn’t accept any relationship with the management of the magazine. The department chose whoever they wanted to employ and the like. When I was hired by Abril, Veja decided that I could do what I liked in the rest of Abril but not there. I developed some interesting work from the institutional point of view and even for education. We created journalism courses that, today, all the journalistic institutions have. We introduced the placement of the best students and afterwards of the others in a position that was called the postman, with the person reading the letters to the editor. Editora Abril received hundreds of letters a day and no one read them, only Veja sometimes picked up theirs. I worked there from 1982 until 1988. During this time, Morte no paraíso [Death in paradise] was launched and I thought I’d like to write another biography. I had another character up my sleeve, Antônio José da Silva. I had already research something, but had come to the conclusion that I had to go to Portugal in order to be able to produce something of the standards that I wanted to reach. I applied for a study grant from the Fundação Vitae and it was approved. Norma and I even had to get married, leaving our things here in an apartment that we had bought. We needed the sum of our incomes to get the financing. It was a fun marriage, which our children attended. She was at JB and became paper’s Lisbon correspondent. Then we went, we rented a nice apartment and those were probably the best years of my life, with the awareness that they were. First, because Lisbon is charming. It is like old Rio de Janeiro. It was the first year that I spent rigorously without thinking about newspapers. I merely read the news. When I was about to come to the end of the period of the grant, I realized I couldn’t leave. The subject had an impressive richness and I’d arrive at home inspired. Exactly at that time, Editora Abril asked if I wouldn’t like to stay a bit longer in Portugal, because they wanted to launch some adult magazines. I eared a reasonable salary, had a car and it was great. It was hard, because in the morning until after lunch I’d be at the Tombo tower, working, poring over material, reading, taking notes. In the afternoon, I’d go to the publisher and at night, write or read at home. I published the first volume of the book in 1992 and started to collect material for the second volume but in 1995, I wanted to return. Fernando Henrique Cardoso had been elected president, Brazil was alive and I didn’t want to be an immigrant outside my country. In 1992, on a trip I had taken for health reasons, I started to see the state at which the Brazilian press had arrived: it was horrible, the triumphalism over the impeachment of Fernando Collor de Mello, that mania for freebies… I thought that it would be very good to found a study center and Luiz Schwarcz suggested that I speak with the president of Unicamp, Carlos Vogt. I knew that Unicamp at some point had wanted to institute a graduate course in journalism because the university’s president at that time, Paulo Renato de Souza, asked Cláudio Abramo for a proposal and he asked if we could work together on this project. Unfortunately, Cláudio died and the project didn’t go ahead. I wrote to Vogt suggesting that we might do some preparatory work. He replied that he was going to Paris and could stop by Lisbon. I put him up at a marvelous hotel in the Rua das Janelas Verdes street. We ate very well and had a great weekend. This was when the idea came up of creating Labjor, Laboratório de Estudos Avançados em Jornalismo (Laboratory of advanced studies in journalism).

So you were partners in the creation of the laboratory?

Vogt already had left the position of university president and said he would join the project as he liked it a lot . He felt that he could make a good contribution to it. He supplied a lot of energy, to me and to José Marques de Melo, who was with us at the beginning of the project but later left for reasons that had nothing to do with Labjor. Anyway, we started to put together the academic bases for the center. By coincidence, at this time, I was traveling a lot between São Paulo and Lisbon, and some young friends of mine, good Portuguese journalists, contacted me to discuss the creation of a journalistic study center in Lisbon. I told them about the Brazilian project and they liked it, so we thought about making twin centers with exchanges. However, that Portuguese pride of not wanting to copy Brazilians and they decided to invent a name. At that time, the Observatoire de la Presse was created in Paris. They came up with the idea to call the Portuguese Center something similar. I thought it was excellent. Then the name Observatório da Imprensa (Press Observatory) was coined and this Portuguese entity was born, of which I am the founder.

What is the name of the Portuguese entity?

Observatório da Imprensa (Press observatory). They named it. At some point, I spoke with Vogt, telling him that we had created Labjor to communicate with society and that it would serve no purpose merely to remain within academia discussing things. Society should say whether the journalism on offer was what it wanted. He thought the rationale was perfect and we started to think about what to do. Magazines were expensive; we tried cycles of talks, but it didn’t work. Then Mauro Malin, one of the younger members of the group, proposed that we do something on the internet. Vogt thought that something could be done at the Uniemp Institute, which had the equipment, and I proposed that we launch the idea of the Observatory (Observatory). I ask our Portuguese colleagues for authorization. Afterwards I remembered the doctrine of the quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg, according to which, when you observe a phenomenon, you interfere with it. I thought “here we have something! Let’s observe the press, and in doing so, the observed will feel the observation and change their behavior.” The thing started and evolved and I saw that it was impossible to do Labjor in Campinas and the Observatorio in São Paulo. We stuck with the Observatório, which was linked to the Uniemp Institute and headed by Vogt. Thanks to him, the internet management committee examined our project and told us that they wanted the internet in Brazil to play a social function. That was where our initial financing, a tiny amount, came from. It was once a fortnight, until Caio Túlio proposed that it be hosted at Uol. We didn’t pay anything, but we were installed in a large portal and this soon raised us to another level. The work increased, we overcame barriers, and we were studied by other Latin American countries, because they have academic mathematical models for evaluating the media, while what we are carrying out is journalism within journalism.

What is your general evaluation of Brazilian journalism today?

Brazilian journalism has an extraordinary vitality and is seductive because of it. However, its quality is falling as time goes by, it’s degrading from within. Still, this doesn’t keep it from generating extraordinary things once in a while. I was moved by the material that Mírian Leitão did on Rubens Paiva. She was an honored professional, working from 5 a.m. to about 11 p.m., doing thousands of things, but she still had time to do the things that her conscience dictate. Because she too had been tortured, and when she was pregnant. She said what she’d do and she did it. A beautiful thing, good, striking and devastating. So Brazilian journalism is capable of doing such things.

In the meeting between the reflections of academia and journalism in its own habitat, do you see a possibility for the creation of new vehicles?

There we enter what the Americans call wisdom thinking. I have hopes that this will occur. I think that we need a big bang, like paft! New things have to appear because Brazil deserves it culturally and Brazil needs it. Brazil will not take a step forward into the world if within it communication is not sound, and has depth. And it must be daily.