NOTIMEX / AFP

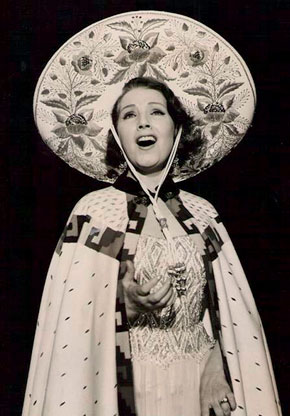

NOTIMEX / AFPLibertad Lamarque in "Cita en la frontera" (1940)NOTIMEX / AFP

In the poem Pneumotórax, Manuel Bandeira, after finding out that he was ill and lamenting “a whole life that could have been, but was not,” hears the following words from the doctor: “The only thing you can do is play an Argentine tango.” Today, perhaps, the Brazilian film industry might not be lamenting “what could have been” if it had depended less on government funding, as the Argentine film industry did in the 1930s, and had resorted to a local version of the “Argentine tango.” “From 1933 to 1942, the Argentine film industry – with its popular musicals based on the tango and on melodrama – enjoyed its golden age. The industry subsisted in its own market , challenging and distinguishing itself from Hollywood competition, and went forward with no State interference. In Brazil, however, the same period, as critic Alex Viany points out, was not as fruitful, despite – or because of – state protectionism,” states Arthur Autran, a professor at the Department of Arts and Communication of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFScar) and author of the study Sonhos industriais: o cinema de estúdio no Brasil e na Argentina (1930-1955) [Industrial dreams: studio-based cinema in Brazil and in Argentina, 1930-1955).

At first, the opportunities to establish a motion picture industry were similar in both countries, but the results were totally different. “Brazil had a numerically reasonable film production, which quickly declined and remained like that until the end of the Second World War. In Argentina, on the other hand, film production increased gradually and achieved impressive numbers: from 1930 to 1940, the number of feature films increased from 2 to 56, a remarkable achievement in an industry comprised of four thousand technicians and actors and 30 motion picture studios,” says Autran.

Both in Brazil and in Argentina, the advent of the movietone sound system motivated film producers, who were encouraged by the existence of audiences for national films, given that the American talkies were spoken in English. It took two years for talkies to adapt to the international market with subtitles and dubbing, and to reach a broader audience, unable to understand the films because viewers did not understand the films’ original language. In addition, film exhibitors did not have the capital to invest in sound equipment.

“It was a unique opportunity; Brazilian and Argentine film producers, after having spent decades experiencing the basic apathy of silent movies, took action to create a local motion picture industry, similar to that of Hollywood, but adapted to local tastes,” says the researcher. Film producers felt it was their “patriotic duty” to prevent the “denationalization” of national cultures, threatened by the Yankee talkies. In Brazil, this “crusade” led to the creation, in 1930, of the studios Cinédia, by Adhemar Gonzaga, and Sonofilms, by Alberto Byington; and 1933 saw the birth of Brasil Vita Filmes, created by Carmen Santos. In Argentina, the “crusade” led to the creation of the Argentina Sono Film (1931), Lumiton (1933) and Rio de La Plata (1934) motion picture studios.

CINEMATECA BRASILEIRA ARCHIVES

CINEMATECA BRASILEIRA ARCHIVES"Alô, alô carnaval", starring Aurora Miranda (1936)CINEMATECA BRASILEIRA ARCHIVES

The Revolution of 1930, in search of “modern means” to implement the program to create a national identity, opened its arms to motion pictures, which raised the hopes of Brazilian film producers. And their hopes came true: in 1932, the new government enacted Decree 21240, which reduced import duties on blank films and obliged movie theaters to show Brazilian-made short feature films before the sessions of imported full length films. “The producers were ecstatic. Still, the State’s actions were insufficient and in the long term proved to be detrimental to the industry, because they took away the opportunity for the national motion picture industry to regulate itself according to market laws without losing its creative freedom,” Autran explains. Creation thus began to be regulated by the State. The government’s “ favors” demanded reciprocal actions, including the power to influence the themes of films and the esthetics of productions, which had to be in line with government projects. The motion picture industry could not complain, as this agreement had been reached to meet the industry’s professional needs. For Brazilian film producers, state patronage was the only means to deal with competition from abroad.

Hollywood

The Argentines, however, proved that there were other ways. “To distinguish itself from Hollywood – which was investing heavily in musicals – and to attract mass local audiences, the Argentine film industry also invested in musicals. But the producers had the insight to bring ‘a taste of Buenos Aires’ to the screen, taking advantage of the successful experience of the ‘sainete’, plays that combined music and comedy, and of the national passion for tango, cultivated as the quintessence of Argentine culture,” says the American historian Matthew Karush, author of The melodramatic nation (2007). By making Argentine films appeal directly to the population – in a way that the Americans had never been able to do – they attracted the working class masses. The Argentine producers’ strategy was to film familiar places where the plots that interested Argentine audiences unfolded.

Brazil also invested in productions with popular music soundtracks, especially samba. However, there were only a few such productions and some were not very successful. The tango was truly a manifestation of a national culture and had a powerful integration that reached out even to the immigrants, who felt – by what they saw on the screens – assimilated into Argentina. The Brazilians, however, did not always identify with the samba once Carnival festivities were over. The reason was that it was the State that imposed the rhythm on the hillside shantytowns converting it into a symbol of nationality. “In both Argentina and Brazil, the critics and the elite frowned at the use of popular music in films, which led some producers to invest in films that were ‘sophisticated’ enough to attract the more lucrative viewers,” says Autran.

CINEMATECA BRASILEIRA ARCHIVES

CINEMATECA BRASILEIRA ARCHIVESGilda de Abreu in "Bonequinha de seda" (1936)CINEMATECA BRASILEIRA ARCHIVES

There was a major difference, however. The Argentine motion picture industry was led by producers with experience in the motion picture market, especially in distribution – the most efficient thermometer to measure viewers’ requirements. The Brazilians lacked this expertise; in addition, they were against the ‘intrusion’ of popular plays and music in motion pictures, even though the success of such films as Alô, alô carnaval (1936), Bonequinha de seda (1936) or Favela dos meus amores (1938) proved them wrong. To the delight of the Argentine moviegoers, the Argentine producers, who were wiser in this respect, soon went back to producing motion pictures starring Gardel, slapstick comedies starred by Sandrini, the poor yet dignified con man, and melodramas starred by Libertad Lamarque, acting as the poor and honest heroine living in a world of wealthy, overbearing people. “The audience identified with these characters and made direct associations with the class divisions of Argentine society, a view that preached the moral superiority of the poor over the rich,” Karush points out. In spite of their conservative plots, Argentine films were socially ambiguous, fostering – and raising – the viewers’ awareness of social class.

The working class made up the bulk of the movie theater audiences. They watched films whose plots focused on the differences between the rich – portrayed as being hypocritical, elitists, and anti-nationalists, and the poor, portrayed as being noble, generous, and nationalistic. “The films featured images of a national identity and emphasized a visible social polarity. Watching them allowed people to dream of a united nation, rejecting the selfishness of the modern elite and celebrating the dignified solidarity of the poor. Counting on the power of motion picture images, this populist Manichaeism became consolidated in Argentine society and gained irresistible appeal which, later on, the Peronist movement would channel to its benefit,” says Karush.

“The expertise of the Argentine producers created a motion picture industry that was able to maintain close contact with local moviegoers. This generated income and, thanks to the exponential growth of the number of films, enabled Argentine motion pictures to be exported to the Latin American market, including Brazil, where the Argentines saw great potential,” says Autran. The Argentines were right in doing so, because the situation in Brazil was radically different. Producers found it difficult to survive, because of the weak ties established between Brazilian moviegoers and local motion picture production. How could any producer be successful in a market totally dominated by American-made feature films, if he could only count on Brazilian-made films, following the State’s “culture-making” parameters?

THE PICTURE DESK / AFP

THE PICTURE DESK / AFPGardel, in the middle, in "Tango Bar" (1935)THE PICTURE DESK / AFP

Nation

“The government was never interested in industrializing the Brazilian motion picture industry. It only wanted to use films as an official propaganda tool for a program that aimed at shaping nationality,” Autran points out. The purpose of Brazilian films was to convey cultural values and unite the nation. Entertainment, which the government despised, could be provided by foreign motion pictures. “Unlike in Argentina, when Brazilian film producers had to choose between the State and moviegoers, they were co-opted and chose the State.”

The Argentines knew how to evaluate the market potential and did not align themselves with the State. “The Brazilians’ decision to align themselves with the government came with a high price tag that is still being charged, a characteristic of the addictive relationship between the Brazilian motion picture industry and the State, which only gets worse as time goes by,” says Autran. The chances were equal, but, ‘with one head’, the Argentines were able to build a strong motion picture industry. It was not until Peron came to power that laws protecting the Argentine motion picture industry were enacted. “Even so, state intervention was restricted to documentaries and news features with political propaganda. Fiction movies never mentioned Peron. This was due to the development model adopted by the Argentine film industry in the 1930s, which resulted in good productions that were unaffected by the State ,” says Argentine historian Clara Krieger, author of Cine y peronismo (2009). “The Argentine film industry underwent a crisis in 1942, especially because of the unclear neutrality of the relationship between the Peronist movement and the Fascists, which led Americans to cut back on exports of blank films for movies, thus rendering film production unfeasible,” she points out. “For many years, the Argentine film industry took images of the lower income segments of the population to the screens.”

Unlike the Argentines, the Brazilians, from the 1950s onwards, invested with great enthusiasm in musical comedies that the Brazilian people could identify with. This combination of popular themes with radio artists, circus performers, and revue artists – that producers had stigmatized for many years – resulted in one of the Brazilian motion picture industry’s most profitable periods. “Burlesque enabled the manifestations of the ordinary people to become the basis of the cultural industry’s repertoire, the industry’s expression of how upset it was with the state taking over the people´s cultural lives, restrictions on speaking out in public, and the suppression of laughter by the seriousness of the government authorities,” Autran points out. Brazil adopted the cambalache genre, although it was late in doing so. The “original sin,” however, had reached the point of no return. “ All over the world, other than in the USA and India, the State provides support for the motion picture industry. But only Brazil does this unconditionally, in the sense that filmmakers need not achieve any market returns. This allows filmmakers to produce extremely expensive films for no reason other than the profit of a very few people,” the researcher adds. As in the past, there is no incentive for the Brazilian motion picture industry to stand on its own two feet; it is still “ dancing” with the State. How can one deal with this when the time to “ play an Argentine tango” is past?

Republish