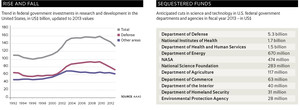

A letter sent in early August to the Congress of the United States and to President Barack Obama, signed by 165 presidents of U.S. universities conveyed the concerns of a good part of that country’s scientific community about the “sequestration” of the federal budget—a provision in force since March that established a hard cap on government spending and imposed a $85.4 billion cut for fiscal year 2013, about $10 billion of which pertained to funds for science and technology. “The combination of the erosion of federal investments in research and higher education, the additional cuts brought about by the budget sequestration, and the voluminous funds that other nations are pouring into those fields has created a new type of deficit for the United States: an innovation deficit,” the letter says. The missive is the result of a campaign led by two associations of U.S. universities. “Ignoring this innovation deficit will have serious consequences: a workforce with fewer skills that is less prepared for the job market, fewer scientific and technological discoveries originating in the United States, as well as fewer patents, start-up companies, products, and jobs.” Obama and Republican lawmakers reached an impasse on the subject of budget limits—and the legislation called for an automatic funding cut in situations of that nature. The question will be discussed again this month. The opposition is proposing cuts in certain social expenditures dear to the government’s heart, while the president’s party is looking for selective cuts, with some tax increases.

A letter sent in early August to the Congress of the United States and to President Barack Obama, signed by 165 presidents of U.S. universities conveyed the concerns of a good part of that country’s scientific community about the “sequestration” of the federal budget—a provision in force since March that established a hard cap on government spending and imposed a $85.4 billion cut for fiscal year 2013, about $10 billion of which pertained to funds for science and technology. “The combination of the erosion of federal investments in research and higher education, the additional cuts brought about by the budget sequestration, and the voluminous funds that other nations are pouring into those fields has created a new type of deficit for the United States: an innovation deficit,” the letter says. The missive is the result of a campaign led by two associations of U.S. universities. “Ignoring this innovation deficit will have serious consequences: a workforce with fewer skills that is less prepared for the job market, fewer scientific and technological discoveries originating in the United States, as well as fewer patents, start-up companies, products, and jobs.” Obama and Republican lawmakers reached an impasse on the subject of budget limits—and the legislation called for an automatic funding cut in situations of that nature. The question will be discussed again this month. The opposition is proposing cuts in certain social expenditures dear to the government’s heart, while the president’s party is looking for selective cuts, with some tax increases.

The science and technology budget in the area of national defense was one of the hardest hit, taking a cut of more than 7%. But the most vehement reaction came from researchers in the biomedical field, who depend heavily on the dollars that flow from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest medical research financing agency in the United States and on the planet. Its budget has declined from the $30.8 billion reached in 2009, to $29.1 billion this year. NIH lost $1.7 billion, equivalent to 5.5% of the expected level. This led to a halt in 700 projects and meant that 750 fewer patients would be served at the NIH Clinical Center. “If the sequester continues, NIH’s financing could fall by between 15% and 20% in the next three years, which would be disastrous,” Anindya Dutta told Pesquisa FAPESP. A professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine, Dutta is one of the researchers affected by the cuts. He says that a lot of laboratories will have to shut down because their supplies and technical staff are paid, in large measure, with NIH funds. Researchers will lose income, because part of their salary comes from appropriated funds. It will also be harder for young scientists to climb the career ladder. “It is expected that we will see students, post-doctoral grant recipients, and even professors looking for jobs in countries like Brazil, India, and China, where investment in biomedical research is expanding,” Dutta believes.

Personal collectionAnindya Dutta, of the University of Virginia: study of muscle regeneration suspendedPersonal collection

Dutta, 54, was born and educated in India but has lived in the United States since 1983. He has identified specific lines of microRNAs, molecules that play a role in the expression of genes responsible for promoting formation of muscle tissue. His research is looking for ways to manipulate the cell differentiation process in muscle tissue, in the hope of developing new treatments for diseases like muscular dystrophy. Five years ago he received $1.3 million from NIH to continue his project, which at the time was classified in the second percentile of the projects submitted to that agency—i.e., it was considered more promising than 98% of all projects. In 2012, when he renewed the request, his proposal was reclassified in the 18th percentile. In previous years, such performance would probably be sufficient to ensure that the research would continue, but because of the sequester, the request was denied. Dutta is looking for other sources of financing and has already warned the post-doctoral fellow who is working with him that he will have to let him go. Now he will have to sacrifice the lab rats on which he is studying cellular differentiation in order to save money. “It’s a huge disaster, because my postdoc will have to find a new group quickly, and the change in laboratory is going to affect his ability to find an assistant professor position. But having to sacrifice our animals before the experiments have been completed, well, that represents a complete waste of time and money,” he says.

Computational methods

Examples like that of Professor Dutta can be found at many institutions. Roland Dunbrack, who heads a laboratory at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, was hit by the budget cut on a grant application for a line of research that is attempting to design, on a computer, molecules of antibodies whose configuration is shaped so as to enable them to fight disease. “The immunological system uses those molecules to fight off infections. There are drugs based on antibody molecules that are being developed to fight cancer and other diseases, when normal cells are not functioning properly. We are using computational methods to design molecules that can be used in treatments,” explains the researcher, who is also a professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

Dunbrack submitted two proposals to NIH in 2012. One of them was accepted, but the antibodies proposal was not. “The project would probably have been accepted if the analysis had been done the year before,” says Dunbrack. He decided to make some adjustments, reducing the scope of his research, since he could only count on having one student available, someone financed by another source. “When the number of appropriations from NIH declines, we have to spend a lot more time writing proposals and much less time doing research. Many of us work at institutions that require that part of our salary—from 25% to 100%, depending on the institution—comes from grants. The same is true for the salaries paid to laboratory personnel. The way things are now, administering a laboratory is a losing proposition,” he says.

The Aids virus

A series of reports on the impact of budget sequestration on scientific research is being published on the news and blog portal The Huffington Post, signed by political affairs journalist Sam Stein (www.huffingtonpost.com/sam-stein/). One of the reports cites the case of Yuntao Wu, a professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at George Mason University, who recently led a promising front line of research on the AIDS virus. His team is studying a compound found in soy that has the potential to block communications between the surfaces and interiors of cells. He thinks this finding may lead to a new treatment to combat the virus.

Evan Cantwell/GMUYuntao Wu: a loan to keep up his research and a plan to go to ChinaEvan Cantwell/GMU

Wu’s attempt to obtain between $100,000 and $200,000 recently failed. He blames the budget sequester, noting that he had received a total of $1.2 million from NIH in the past four years. To deal with the crisis, Wu dismissed a technical staffer, suspended some projects, and has submitted ten new research proposals since February. He also took out a loan for $35,000 so as not to interrupt his work, but is already considering a Plan B. He announced that he is expanding his collaboration with groups in his native China, where he thinks he may move if the situation in the United States does not improve.

The reports in the Huffington Post provoked a variety of repercussions. “Some in the political world think the reaction is overblown, since at $29 billion, financing from the NIH is still robust,” Sam Stein wrote. “Even with sequestration, their budget is dramatically higher than it was during the Clinton administration, even when figures are adjusted for inflation.”

In January 2002, then-President George W. Bush announced a plan to double the NIH budget within five years. That would mean that the agency could spend $29.2 billion in 2007, an increase over the $20.4 billion in 2002. It is to that 2007 level that NIH funding returned in 2013, leading to the suspension of 700 research projects.

The Huffington Post reports were met with enthusiasm in the scientific world. Several letters with testimonies from researchers who told of their troubles were published. At the end of August, Stein interviewed NIH Director Francis Collins, whose tone was dramatic. “God help us if we have a worldwide flu pandemic in the next five years,” said Collins, referring to research being done on a universal vaccine against the flu. He thinks a vaccine could be achieved within a five-year horizon if it is possible to save that line of research from the budget sequester. This month, the U.S. Congress will debate the budget limits for fiscal year 2014. The expectation, according to government sources, is that it will implement a selective policy of cuts that may suspend the “sequester.” If the impasse is not resolved, the number of research projects being cut will probably increase next year.

Republish