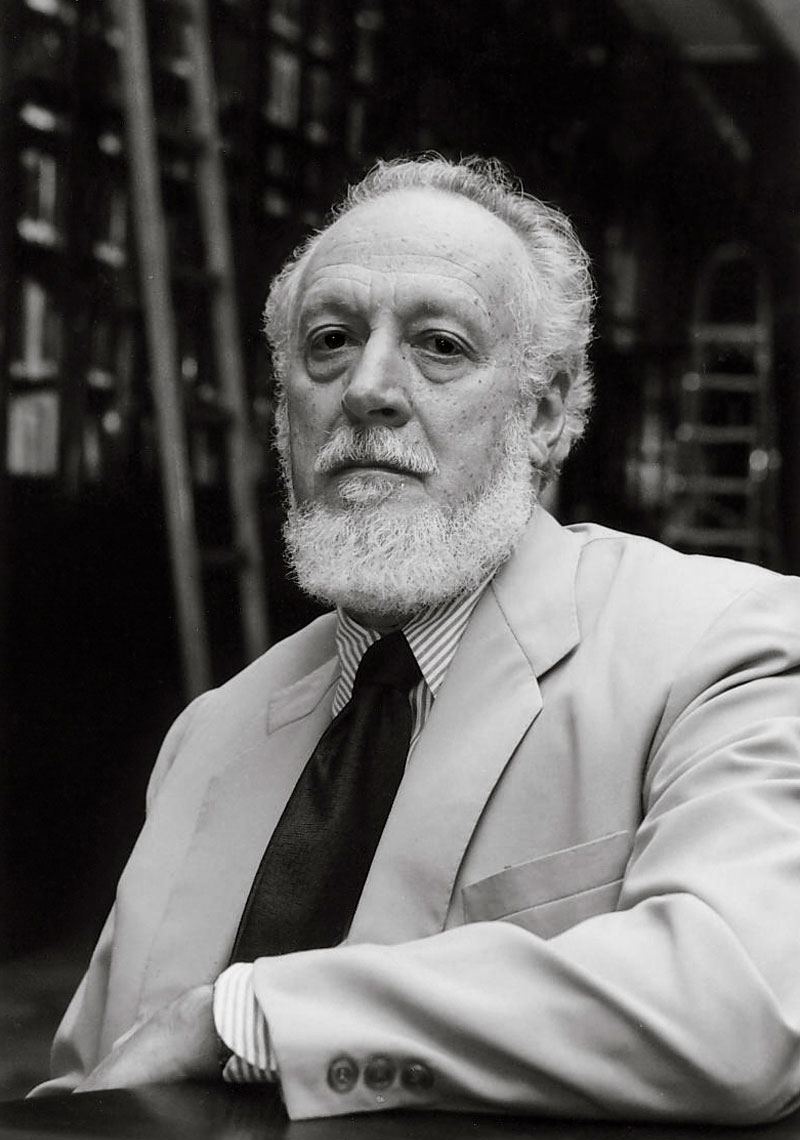

Bel Pedrosa / Companhia das LetrasAlberto da Costa e Silva in 2005: despite not having pursued an academic career, he became an indispensable authority among researchersBel Pedrosa / Companhia das Letras

Diplomat and historian Alberto da Costa e Silva was someone who “turned his distraction into a craft,” in the words of historian Mariza de Carvalho Soares, of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). In parallel to his career at the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Itamaraty), which began in 1957 and included posts at the Brazilian embassy in Nigeria (1979–1983) and, cumulatively, in Benin (1981–1983), in addition to Portugal (1986–1990), Colombia (1990–1993), and Paraguay (1993–1995), Costa e Silva maintained an unwavering interest in Africa’s history, which resulted in nine books on the subject. Despite not having pursued an academic career, he became an indispensable authority among historians and other researchers.

Costa e Silva, who died in Rio de Janeiro on November 26, at the age of 92, is recognized for his pioneering dedication to the African continent. “The West turned a blind eye to Africa, as did Brazil. We attached much more importance to our mythical, Greco-Roman history. Alberto da Costa e Silva, on the other hand, was a scholar of the various Africans who docked in Brazil,” summarizes anthropologist and historian Lilia Mortiz Schwarcz, of the Faculty of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP). “He not only studied the slave trade, but also the continent before commercial slavery,” continues Schwarcz, one of the editors of the book Três vezes Brasil: Alberto da Costa e Silva, Evaldo Cabral de Mello, José Murilo de Carvalho (Three times Brazil: Alberto da Costa e Silva, Evaldo Cabral de Mello, José Murilo de Carvalho; Bazar do Tempo, 2019).

Historian Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, of the Getulio Vargas Foundation’s São Paulo School of Economics (EESP-FGV), highlights that before 2003, with the enactment of Law no. 10.639, which required that African history be taught in high school, Brazilian universities paid little attention to the subject. “He was genuinely interested in the continent. For a long time, he was the sole spokesperson in the country,” states Alencastro.

One of his most well-known works is A enxada e a lança: A África antes dos portugueses (The hoe and the spear: Africa before the Portuguese; Nova Fronteira, 1992), which covers the entire period from prehistory to the 15th century. The book was intended to be the first volume in a trilogy, whose second volume, A manilha e o libambo (The shackle and the yoke; Nova Fronteira, 2002) covers the 16th to 18th centuries. For this work, he received the Jabuti and Sérgio Buarque de Holanda prizes, attributed by the National Library. The third volume, which would have focused on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when Africa was divided between colonial powers and then went through wars of independence, was never published.

If Brazilian historiography of the first half of the century left the close ties between Africa and Brazil in the shadows until the nineteenth century, Costa e Silva was one of the first to reinforce the importance of the connection between cities like Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and Luanda. The expression used in the title of one of his books sums up the intensity of this interaction: Um rio chamado Atlântico: A África no Brasil e o Brasil na África (A river called the Atlantic: Africa in Brazil and Brazil in Africa; Nova Fronteira, 2003). “Today, the concept presented in his work is well established. This references the circularity that took place across the Atlantic, involving techniques, knowledge, philosophies, cuisines, and languages. Alberto brings a pioneering vision and tremendous influence to this discussion,” says Schwarcz.

Born in São Paulo, Alberto Vasconcellos da Costa e Silva grew up in Fortaleza (Ceará), where he moved with his family when he was 2 years old. As a poet, he published nine books, two of which received the Jabuti prize: Ao lado de Vera (Alongside Vera; Nova Fronteira, 1997) and Poemas reunidos (A collection of poems; Nova Fronteira, 2000). He was appointed to the Brazilian Academy of Letters (ABL) in 2000, occupying chair no. 9, and was president of the institution in 2002 and 2003. The historian and diplomat was a widower and left behind three children, seven grandchildren, and a great-granddaughter.

Republish