Ormuzd Alves/Folhapress

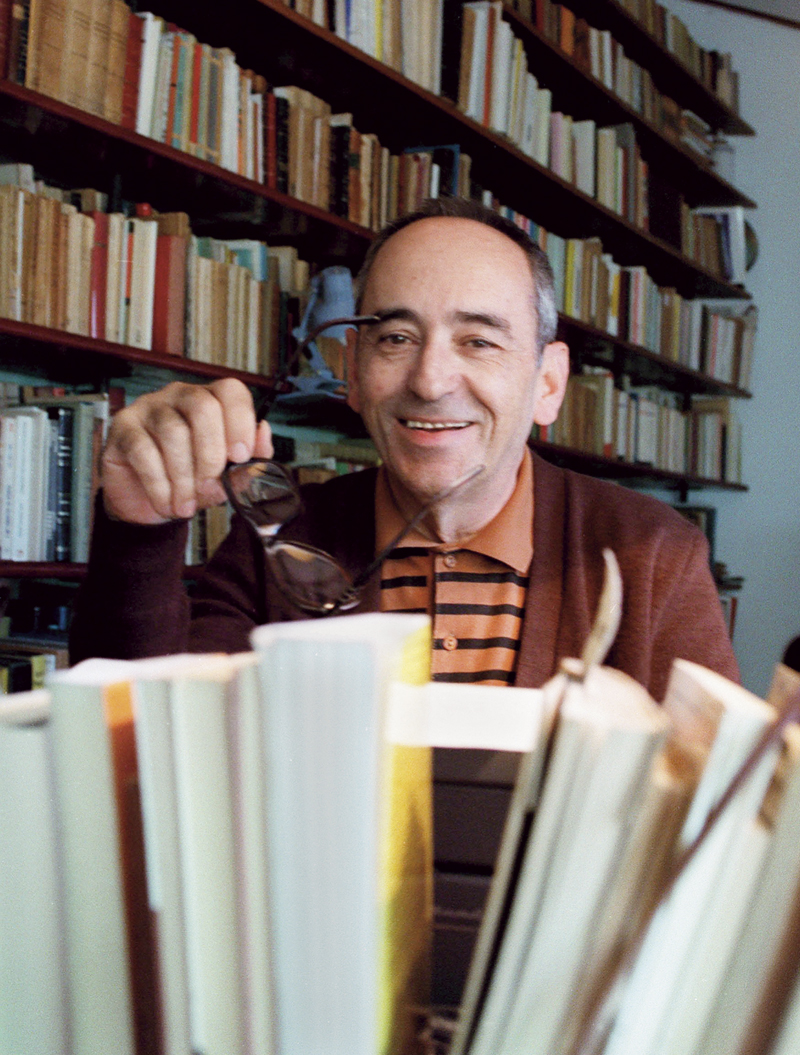

José Paulo Paes, in 1991, in his home library in the city of São PauloOrmuzd Alves/FolhapressWhen he published his first book of poems, in 1947, José Paulo Paes (1926–1998) sent it to Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902–1987), who was already an established author at the time. In a letter, the seasoned writer advises the beginner to overcome influences and find his own voice: “You have an undeniable poetic flair, you handle free verse with a fair amount of rhythmic confidence, you never slip into poor taste—but you don’t yet seem like yourself to me, you’re still looking for yourself through others, when it’s within yourself that you have to find yourself.”

By making his literary debut with the suggestive title O aluno (The student; Edições O livro), Paes positioned himself as a kind of pupil of Itabirano and other modernists to whom he paid homage, such as Manuel Bandeira (1886–1968) and Murilo Mendes (1901–1975). Paes’s literary affinity with Drummond is well known to researchers. However, few scholars know that only one year later, the pupil did not spare the master, this time in the role of literary critic. In 1984, in a series of essays published in Curitiba’s O Dia newspaper, the 21-year-old, who at the time was linked to revolutionary ideals and the Communist Party, classified Drummond’s socially themed poetry as “escapist poetry,” representative of the petty bourgeoisie, due to its tendency to transpose concrete reality to the abstract plane. When analyzing the use of humor in Drummond’s poetry, Paes contrasts it with verses by two poets: Georgian poet Vladímir Maiakóvski (1893–1930) and Bahian poet Castro Alves (1847–1871), who, in the critic’s opinion, were effectively revolutionary.

The texts “Carlos Drummond de Andrade and humor – I, II, and III,” which at the time were not published in book form, are now part of the collection José Paulo Paes: Crítica reunida sobre literatura brasileira & inéditos em livros (A collection of critiques on Brazilian literature & unprecedented in books; Cepe Editora/Ateliê Editorial). With more than 1,000 pages, the two-volume work includes essays by Paes centered on Brazilian literature. “From a critical point of view, it can’t be said that José Paulo followed a specific playbook, whether that of Antonio Candido [1918–2017] or Roberto Schwarz,” says Fernando Paixão, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Brazilian Studies Institute (IEB-USP) and organizer of the collection together with literary critic and researcher Ieda Lebensztayn, responsible for locating the unpublished texts. “He was similar to the concretists, but more in terms of his poetic work than theoretically. In his critical analyses, José Paulo has always been free.”

Family's personal collection

Paes and the literary critic Alfredo Bosi (in a suit), who became friends in the 1960sFamily's personal collectionThe new collection features critical reviews by chronological order of publication, as well as unpublished texts. It covers a variety of themes ranging from Augusto dos Anjos’s (1884–1914) poetry to Adoniran Barbosa’s (1910–1982) samba, as well as reflections on translation, the presence of surrealism in Brazil, and the revival of lesser-known figures such as the Bahian poets Sosígenes Costa (1901–1968) and Jacinta Passos (1914–1973). His essays reveal an eclectic critic, with a vision of literature that, according to Sergio Bento, a Brazilian literature professor at the Federal University of Uberlândia (UFU), has always been devoid of prejudice. An example of this, he says, is the article “Por uma literatura brasileira de entretenimento (ou: o mordomo não é o único culpado)” (For a Brazilian entertainment literature [or: The butler is not the only culprit]),” originally published in the book A aventura literária: Ensaios sobre ficção e ficções (The literary adventure: Essays on fiction and works of fiction; Companhia das Letras, 1990). In the book, the critic argues that less prestigious genres such as detective novels, science fiction, and adventure novels should be judged not only by aesthetic literary criteria, but also through a lens that considers the sociology of taste and consumption. Paes argues that, after all, the readers of Agatha Christie (1890–1976) and Alexandre Dumas (1802–1870) become admirers of James Joyce (1882–1941) and Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880).

However, in the article, the intellectual laments that, in the late 1980s, publication within these genres was still incipient in Brazilian literature. “Paes was not linked to the university, and he didn’t even have a degree. He began teaching classes at UNICAMP [University of Campinas] and USP, but as a guest professor. Along with Augusto de Campos, he was a renowned twentieth-century critic untethered to academia,” states Bento, author of a dissertation on Paes’s poetry, defended in 2015 at USP’s School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH). “As such, he could break away from a certain cultural elitism that only deemed high literature relevant. Paes realized that people read for entertainment, which was uncommon for the average Brazilian critic at the time.”

One of the most striking aspects of Paes’s essayism, according to historical and literary critic Alfredo Bosi (1936–2021) in a testimonial included in the collection, is precisely his breadth of interests and tastes, and the distance he maintained from “narrow-minded aesthetic theories, tending towards categorical judgments.” His curiosity for all kinds of literature surprised the author of História concisa da literatura brasileira (A concise history of Brazilian literature) when the two became friends in the mid-1960s. In his encounters with Paes, who he described as “a free, unrestricted reader” and “an observer without parti pris,” there was a reversal of roles. Bosi, who was a professor of Brazilian literature at USP for more than four decades, recalls: “It was the self-taught José Paulo who taught the university professor. The professor learned to reread with new eyes what he had already read as a literature professional.”

Family's personal collection

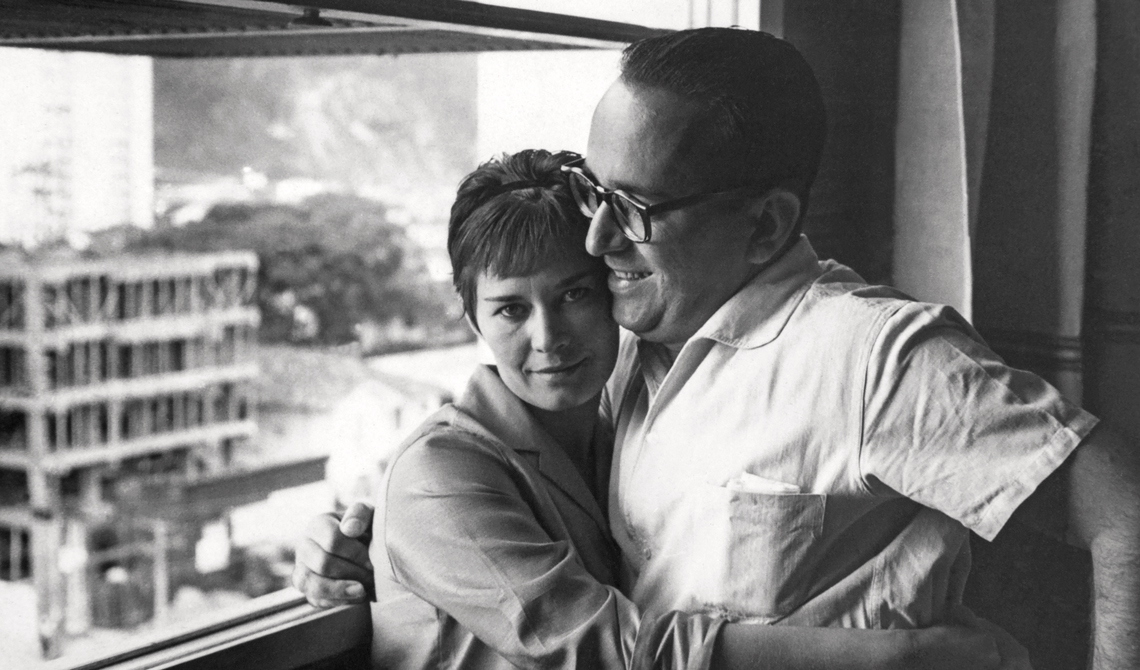

With his wife, ballerina Dora Costa, to whom he dedicated his second book, Cúmplices, in 1951Family's personal collectionBorn in Taquaritinga (São Paulo), in 1926, Paes came from a lower-middle-class family of Portuguese descent. In the 1940s, he migrated to Curitiba, where he studied as a chemistry technician and began socializing with writers and intellectuals such as Dalton Trevisan. It was in the capital of Paraná that he began collaborating with the press, making his literary debut by publishing O aluno (The student). “At the time, Dalton was an editor for the magazine Joaquim, publishing unpublished works by poets such as Drummond and Bandeira. Before that, Curitiba’s literary scene stemmed from nineteenth-century symbolism. Modernism arrived in the city through Dalton’s magazine,” says Marcelo Sandmann, who researched Paes’s poetry in his master’s thesis and who is currently a Portuguese literature professor at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR). “Paes already knew the Romantics and the Parnassians, but it was through his connection with writers from here, especially Glauco Flores de Sá Brito [1919–1970], that he discovered Brazilian modernist poetry.”

The poet moved to São Paulo, in the late 1940s, to work in the pharmaceutical industry, where he remained for 11 years. During that time, he met ballerina Dora Costa, whom he married and to whom he dedicated his second book, Cúmplices (Accomplices; Edição Alanco, 1951). Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, the author developed a style that was difficult for researchers to classify. Chronologically, he belongs to the 1945 generation, but he has a chameleon-like ability to span several periods of Brazilian literature, without adhering to any one group. With Novas cartas chilenas (New Chilean letters; a 1954 poem published two years later in Revista Brasiliense) and Epigramas (Epigrams; Editora Cultrix, 1958), the “student” begins demonstrating his distinct voice, reaching maturity with Anatomias (Anatomies; Editora Cultrix, 1967), a book presented by concretist Augusto de Campos in which his writing takes on an experimental nature, marked by concision and humor.

In 1984, he broke into children’s poetry by publishing É isso ali (That’s it; Editora Salamandra), gaining widespread recognition. And, in 1997, one year before his death, he won the Jabuti prize for Um passarinho me contou (A little bird told me; Editora Ática). “When we discuss children’s poetry in twentieth-century Brazil, the names Cecília Meireles [1901–1964], Manoel de Barros [1916–2014], and José Paulo Paes come to mind,” notes Bento. “His children’s poems are delightful: they explore rhymes, puns, paranomasias [words similar in sound but different in meaning.] That’s why they were more impactful than his poetic work without age restrictions.”

Family's personal collection

Paes (wearing glasses) at an event (undated) attended by Bahian novelist Jorge Amado (at the microphone)Family's personal collectionPaes, who worked in the publishing sector as an editor at Cultrix in São Paulo from the 1960s to the 1980s, was mild-mannered in nature, which may have contributed to his work receiving little attention from scholars. Among the few reviews of the author are, for example, a preface by Alfredo Bosi for the anthology Um por todos (One for all), published in 1986 by Editora Brasiliense, and another by literary critic Davi Arrigucci for the anthology Os melhores poemas (The best poems; Global, 1998).

This small sample has now multiplied with the release of another collection: Anatomias da meia-palavra: Ensaios sobre a obra de José Paulo Paes (Anatomies of the half-word: Essays on the work of José Paulo Paes; Editora UFPR, 2022), which features articles written by seven researchers, such as Bento and Sandmann, covering various facets of his work. The collection was organized by Marcos Pasche, a Brazilian literature professor at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), and Henrique Duarte Neto, a PhD in literature from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC). According to Pasche, the great legacy Paes has left on contemporary Brazilian literature is the autonomy that defines his poetic journey. “Paes had important counterparts, such as the concretists, but he never abandoned, for example, his ongoing relationship with ancient Greek culture, which was cemented through his work as a translator.”

In one of the collection’s articles, Susana Scramim, a literary theory professor at UFSC, writes that translation is not a secondary aspect of Paes’s work, rather it reverberates throughout his writing. Drummond even encouraged him to learn languages. In the same letter from 1947, the poet from Minas Gerais recommended reading foreign authors in their original language as an antidote to the crude imitation of national models. Following his mentor’s advice, Paes became a self-taught polyglot: he learned Spanish, French, English, German, Modern and Ancient Greek, Danish, and Italian. He translated works by authors such as William Carlos Williams (1883–1963) and Nikos Kazantzakis (1883–1957) into Portuguese. He translated Ascese: Os salvadores de Deus (Ascesis: The Saviors of God; Editora Ática), written by the Greek author, which won the Jabuti prize in 1998.

Reproduction

Book covers for some books written by the author, who wrote poetry for children and adults. The work Um passarinho me contou won the Jabuti prize in 1997ReproductionTowards the end of his life, Paes’s poems were marked by the memorialist tone he adopted to delve into his childhood and evoke family memories of Taquaritinga in the book Prosas seguidas de odes mínimas (Prose followed by minor odes; Companhia das Letras, 1992). This stylistic turn coincided with a tragic biographical event: the amputation of his left leg due to a circulatory issue. Even in the most grave moments, however, the lesson of humor, which he inherited from Drummond and carried throughout his life, prevented the poet from surrendering to cheap sentimentality: “Legs/ for what do I want you?/ If I no longer have/ anything to dance for./ If I no longer want/ to go anywhere anymore./ Legs?/ One is enough,” he writes in “Ode to my left leg.”

Twenty-five years after José Paulo Paes’s death, academic studies on the author are expected to become more in-depth with the incorporation of his collection at IEB-USP, scheduled to occur by the end of 2023. “We want to focus on Paes’s essays that were left out of the collection and continue researching him,” concludes Paixão.

Republish