Léo Ramos ChavesIn 1983, during an internship at Sloan Kettering Memorial Hospital in New York, Drauzio Varella realized that AIDS would hit hard in Brazil. Although he already had more than ten years of experience in oncology and was accustomed to seeing seriously ill patients, the HIV-positive patients he saw in the United States made an impression on him. They were all young people, many of them artists and intellectuals. “I was very touched by the experience,” he recalls. “I had the unmistakable feeling that a tragedy was about to happen.” He began to study the subject. When he returned to Brazil, he was the only oncologist with experience in disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare type of cancer common in AIDS patients. Because infectious disease specialists had little experience with the new illness, Drauzio began to treat AIDS cases himself at the Hospital do Câncer, in São Paulo. They came in from around the country.

Léo Ramos ChavesIn 1983, during an internship at Sloan Kettering Memorial Hospital in New York, Drauzio Varella realized that AIDS would hit hard in Brazil. Although he already had more than ten years of experience in oncology and was accustomed to seeing seriously ill patients, the HIV-positive patients he saw in the United States made an impression on him. They were all young people, many of them artists and intellectuals. “I was very touched by the experience,” he recalls. “I had the unmistakable feeling that a tragedy was about to happen.” He began to study the subject. When he returned to Brazil, he was the only oncologist with experience in disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare type of cancer common in AIDS patients. Because infectious disease specialists had little experience with the new illness, Drauzio began to treat AIDS cases himself at the Hospital do Câncer, in São Paulo. They came in from around the country.

Two years later, during a medical conference in Stockholm, Sweden, upon leaving a major discussion about the AIDS epidemic, the oncologist found himself thinking about another aspect of the disease, prejudice, and how to deal with it. “At that time, the ignorance was brutal. This is happening in Brazil and nobody’s going to say a thing?” Thus began a journey that would make him the best-known doctor in the country, first over the radio, then followed by television, print journalism, books, and the internet.

While he describes it as an educational project effected through the vehicles of mass communication, his communication work covers a multitude of themes and subjects, which sometimes extend beyond healthcare. He doesn’t shy away from controversy—at age 76, conscious that life is finite, he gives himself permission to say what he thinks. In his writing and public appearances Drauzio speaks out on abortion rights, decriminalizing drugs, and the ineffectiveness of mass incarceration as a policy for combating violence.

Married to actress Regina Braga since 1981, the father of two daughters from his first marriage, and a grandfather of two, the São Paulo oncologist divides his time between patients, communication, and writing, a source of happiness for him. In this interview, he tells us about his research activities, complains about the lack of importance Brazilians attribute to the Unified Health System (SUS), and talks about his communication work and his strong relationship with the prison world, where he learned to appreciate cachaça [Brazilian rum].

Specialty

Oncology

Institution

Member of the clinical staff of the Sírio-Libanês Hospital

Education

Medical degree from the University of São Paulo (1967)

Production

16 scientific articles and 16 books, among them Estação Carandiru

Among all your activities, your work related to scientific research is certainly the least known. How did your work with plants from the Amazon come about?

On the weekend of the Carandiru massacre in October 1992, we organized a course on biotechnology in AIDS and cancer at a hotel in São Paulo. Biotechnology was just beginning; it was the hottest area in biology. Brazil had very little of it, and we wanted to bring the top people here to draw attention to the field. I talked to a friend at the Cleveland Clinic, Ron Bukowski, about organizing a course. He told me: “Brazil is off the beaten track, internationally. If you want to bring people there, you need to offer a tour, a weekend at the beach…” Since UNIP [Paulista University] had a boat on the Amazon, the Escola da Natureza (Nature School), a typical Amazon riverboat, I thought, “What if I took these people there?” And he replied: “With that you could get whoever you want, even Robert Gallo.” Gallo, at that time, was deservedly at the top of AIDS research. We did the course with more than 20 guests—including Gallo, and it was broadcast to 20 auditoriums in a variety of cities by EMBRATEL and sponsored by UNIP, with which I had an informal connection.

And from that trip a project was born?

From the boat you can’t see a single plant that’s like any other on the shore. Observing this biodiversity, Gallo asked, “From the biological point of view, do you have any screening studies being done here?” He wanted to know if plant extracts were systematically analyzed and tested for treating diseases. It stayed in the back of my mind. As we had the necessary infrastructure, we could start up a project. I went to talk to [João Carlos] Di Genio, owner of the Objetivo private schools and UNIP. I’d had only occasional contact with him, but he has one characteristic, he perceives when things are interesting, and you don’t need to do much explaining. “How do you want to do it?” he asked. First we need to learn, I explained. I contacted Gordon Cragg, head of the natural products sector at the National Cancer Institute [NCI], which has the world’s largest cancer screening project. I went there and he said that they had lost interest in Brazil because of the biopiracy charges. But he did offer technical support; we could send people that they would train. We would have to learn to do the extractions, and then it would take rigorous taxonomy work because if there’s any error in plant classification, everything is lost. The most respected researcher in the field of Amazonian plant taxonomy, Douglas Daly, worked at the New York Botanical Garden. I left the NCI and went to New York to meet him. I found an American speaking Portuguese with the accent of a backwoods Amazonian: “Rapaaaaiz…” [Duuude…] He was passionate about Brazil, and had an ongoing project with the Federal University of Acre. We set up a herbarium, and sent a young woman who’d recently graduated from the University of São Paulo [USP], Ivana Sufredini, who learned all the technical part of extracting. She came back here and set up the lab, then returned to NCI to test the extracts on medical tumor lines that they gave us.

What was that experience like?

It was an epic. To collect the plants, we needed a permit from IBAMA. At that time, it was a tragedy. We would deliver the project paperwork, which fell into a black hole. It went on like that for years. We collected everything we could. UNIP today has the largest extract collection from the Amazon forest, 2,200 extracts. We found five extracts with more intense antineoplastic activity, which are being studied. It’s a very interesting research project, which also depends on FAPESP funding. We have produced and published a lot.

How did you choose oncology?

I graduated from USP in 1967. I started a residency in public health, but I got discouraged, it was very theoretical. I wanted to get my hands dirty, to work in a health clinic. I studied parasitology with Luis Rey, one of the greatest Brazilian authorities in malaria. He was kicked out of the university in 1964, along with Erney Plessmann de Camargo and Luiz Hildebrando Pereira da Silva. I had a lot of admiration for the three of them. I created a movement and we chose Luiz Hildebrando as our commencement speaker. As the college’s board had declined to attend the graduation, it was unofficial. Rey returned to Brazil in 1969 and was hired by the Faculty of Public Health, only he needed to get the public health degree, so he was my colleague. I thought, “A world-renowned guy is sitting here taking this course. I don’t want this to be my future.” The Secretary of Health had created the position of public health official, but the salary was the same as my rent—and I was already married. It was the era of the dictatorship; I would teach in the college prep school at night, and go out and meet with the staff of Jornal da Tarde [an important new daily newspaper at the time] and stay up talking into the wee hours. One day I met Vicente Amato Neto, an infectologist my class thought very highly of. I told him I was lost, and he suggested that I study MI [infectious diseases] because I had a connection with public health. He invited me to do an internship at the Public Employee’s Hospital. At his suggestion, I began to take more interest in the immunological aspects of infectious diseases. Modern immunology was making great strides in the early 1970s. Alois Bianchi, the greatest pediatrician we’ve ever had, invited me to give an immunology class at the Hospital do Câncer. I went and I ended up staying.

In the research done with Amazonian plants, we arrived at five extracts with intense antineoplastic activity, which are under study

What did you start working on there?

At that time I began an experiment with the use of BCG [the tuberculosis vaccine] for the treatment of malignant melanoma. When I gave that class, the medical staff came to ask for help. It was a new thing, nobody knew anything about cancer immunology. As I had already been reading up on it, I said that when there was a melanoma case, I would like to see it. I started going one morning a week, and received some cases of melanoma. One of these was a man who’d had melanoma on his arm and was beginning to have nodules in various places. I proposed to try to treat him with oral BCG and see what happened. The lesions began to redden. I photographed and removed one of them. After a while, they began to turn very red and regress. A few months later, they completely disappeared and left a white halo in their place, which is characteristic of melanoma rejection. I was fascinated. After we had seen other cases, we published in the journal Cancer in 1981, which was the first Brazilian research in the magazine. I presented these results twice at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, which was the mecca of world oncology. It was one of the first scientific demonstrations—of well-studied cases, including images—that it was possible to stimulate the immune system and provoke tumor rejection at a distance. That’s how I became an oncologist.

How did the shift from oncology to AIDS come about?

At the end of 1981, Joe Burchenal, the head of oncology at Memorial was in Brazil. At lunch one day he commented that there were cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia that had appeared in New York in apparently non-immunocompromised young men. At the same time, in San Francisco cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma were appearing in young men, by coincidence, homosexuals, like those in New York. I went after the Morbidity and Mortality Report from the CDCs [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the United States] read the case descriptions, and became very interested. Here we had a disease caused by an infectious agent, probably a virus, which caused immune deficiency, opportunistic infectious diseases, cancer—disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma—in young homosexuals. I went to Memorial in 1983 and stayed for three months. There was a researcher there, Susan Krown, who was working with interferon in Kaposi. I was shocked because the patients were all young, mostly intellectuals, writers, journalists, and painters. I started studying like crazy. When I returned to Brazil, I was the only oncologist who had experience with disseminated Kaposi. I began to treat the first cases. Infectious disease specialists had little experience with it. I treated people from all over Brazil at the Hospital do Câncer. I was consumed by the AIDS epidemic.

Was that when you started your health communication work?

At that time, the ignorance was brutal. They called it a gay plague, which was meant to say that women or heterosexuals weren’t at risk, nor those taking drugs through intravenous injection. In New York I realized that a tragedy was about to happen in Brazil.

What did you do?

I was good friends with Fernando Vieira de Mello [1929–2001], director of Jovem Pan radio, who was an excellent journalist. He said, “You have to give an interview on the radio, it’s no use just talking to me.” I resisted quite a bit. At that time, a doctor who spoke in the mass media was viewed negatively. I gave the interview, it was long, and he broke it up into segments that were inserted in the program schedule. I complained, “You can’t do things like that, I’m going to have problems with my colleagues, I’m supposedly a serious doctor.” He replied, “Do you want to be in good with your colleagues or get this information out to the people?” That swayed me. I returned to the station after a few days and asked what I needed to do. He explained that the messages transmitted on the radio have to be short, and shouldn’t exceed two minutes. You have to introduce yourself. And direct your message to the group you’re trying to reach, it’s no use talking to everyone. “I am Dr. Drauzio Varella talking to those of you who are young and homosexual; to you who take intravenous drugs.” For each group it’s a different language.

Personal archive

UNIP’s boat Escola da Natureza, used to collect plants in the AmazonPersonal archiveAnd your colleagues?

No one ever said anything to me. I was sure that this kind of communication was important. I’d see people talking about it on the street, talking to me, ordinary people. I thought, “That’s what I want to do.” If anyone thinks I just like the attention, it’s their problem, not mine. To this day I hear people saying that I was born for this job—it’s not true. It’s training. I gave classes at prep school for 20 years, beginning in my first year of college. My father had four children, two jobs; I couldn’t go to college without working. Objetivo [a network of private schools], which I helped to found and which I named, eventually had 25 classes of 400 students. We gave the same class 25 times a week. Teenagers don’t quiet down even at the movies; you have to keep their attention. It was a long process. It’s not talent, it’s training.

From working with AIDS, how did you wind up at Carandiru?

Because of the radio broadcasts, I was asked to make a video about AIDS. We did it with a professional producer, who shot it on Indianópolis Avenue, in São Paulo, a transvestite hangout in the red-light district, and in the prison. In Brazil we have conjugal visitation, and no precaution was taken to help those women, to inform them. We filmed at the state penitentiary and I spent the day there. In the infirmary there were people dying, with cachexia [a wasting condition]; it was a tragedy. The experience made a deep impression on me. Ever since I was a kid I’d liked prison movies. There are people who are attracted to this environment, I’ve met other people like that. I spent the next few days thinking about the prison; my wife said she’d never seen me so quiet. After a few weeks, I went to the head of the medical department of the São Paulo penitentiary system, Manoel Schechtman, and offered to do volunteer work. He said that the biggest problem was at the São Paulo Detention Center, Carandiru, which had more than 7,000 people, and nobody wanted to work there. I went to talk with its director, Ismael Pedrosa [1935–2005]. My thinking went like this: “First, we need to demonstrate what’s happening here, how many people in here are infected.” From that number, we define what should be done.

How did you begin?

I proposed to do a survey with the people who received conjugal visits. It was a significant sample; there were 1,500 people enrolled in the program. I got a donation of test kits, and the collection work could be done by the users in the prison, the “mainliners,” who know how to find a vein better than anyone. I spoke with the director and he brought me five prisoners. I asked, and they had experience. “We can get a vein with a crooked needle, with this equipment of yours it’s child’s play,” one of them replied. We collected blood from 1,492 people. We tested it, and 17.3% of them were infected. Of the transgender people imprisoned there for more than six years, 100% were infected. I started using this data to talk to the authorities. At a minimum we needed to distribute condoms for the conjugal visits and alert the women, and send them to the health clinics. No one wanted to hear about it.

But you insisted…

Jail is the right place to spread this kind of information. Where do 7,000 criminals get together? They spend time in jail, they go back on the streets, they spread throughout the entire city, and then they to back to jail. The information transmitted inside can be disseminated throughout the city to a group that’s unreachable outside the prisons. I proposed to the director that I give lectures on AIDS. UNIP donated the big screen and the microphone. I did two or three and realized it wasn’t going to work. I wanted to do a systematic job, to the whole prison. Then Valdemar Gonçalves, the prison director, appeared and organized it so that each session would be seen by one floor of each cellblock. At 8 a.m., they would open these cells first, then the prisoners would come down and see the lecture. This was before opening the other floors; otherwise the others would have mingled in. We held a meeting with the prisoners who were the chief custodians of each cellblock. At the time there was no PCC [First Command of the Capital, a large organized crime gang throughout the state prisons], the chief custodians were in charge of the prison. They were watching people die; the epidemic wasn’t theoretical for them. We explained that we wanted to pass along information, but there could be no incidents. If someone died, it would end our work. They said, “You can rest easy, nothing will happen.” Another problem was getting the prisoners out of bed at 7:50. Delinquents don’t wake up early for anything. Then Valdemar had the idea of showing a pornographic film. After the lecture, we’d leave the room, “so as not to lose their respect,” and they showed the film. It was a package deal: you come in, the door closes, and you stay until the end. It worked beautifully. I did those lectures for about ten years.

Personal archive

Drauzio interviews residents of Acre State about malaria for the national weekly television program Fantástico, in 2018Personal archiveSo you went from that to attending physician?

When I finished a lecture, people would stop me in the corridors. “Uh, doctor, look at this…” They would line up, it looked like a cour des miracles. I began attending one day a week. It lasted until 2002, when the prison was shut down.

Is your relationship with the prison still strong?

Carandiru was an unforgettable prison. It’s not just me: the guards, who I still meet with even today, agree. I took a particular liking to walking around in it alone, going into the cells, to being respected in that environment due to the exercise of my profession. It wasn’t for my own personal value. The social interaction was lasting, direct. The prison guards stood by, went up, and entered the cells. There were always factions and their function was to keep them from uniting. A guard once told me, “Their business is to grab power in jail; ours is to throw a monkey wrench in the works.” If they started getting together, they’d take one out, transfer another in, and they were able manage things like that. Cellblock 8 had 1,200 repeat offenders, and five or six employees watching over them. They have a very impressive knowledge of human nature. After the massacre, in 1992, the relationship changed. When something like that happens, it was pretty clear that it wouldn’t happen again. No one was going to send in the Military Police again, a week later. The prisoners began to thrive, to take over. The state was forced to retreat, to let up, and the power vacuum didn’t stay empty. Immediately, it was occupied, and the factions began to take control. It was the beginning of the PCC.

Back on the topic of AIDS, what is the role of the media today?

It has to specifically target at-risk populations. It can’t have, at this point in time, bias against homosexuals, transgender people… There is repression embedded in the discussion, of not speaking clearly, of offending families. Eleven thousand people die every year in Brazil as a result of AIDS and we’re going to be worried about prejudice?

It’s something like abortion.

It’s the same thing. I once attended a meeting with the teacher Mario Sérgio Cortella and a young rabbi from Rio, Nilton Bonder. When it was the rabbi’s turn, they asked: “How do you see the abortion question?” He said: “In Judaism life begins when the child is born.” Period. Some people think that life begins when the sperm enters the egg. One can also think that human life is characterized by the functioning of the central nervous system. What you can’t do is impose the same way of thinking. Women lose their lives having unsafe abortions.

The Unified Health System, SUS, was the greatest revolution in Brazilian healthcare history. There is nothing comparable.

What is the most difficult issue to resolve in Brazilian public healthcare?

Organization. We have the basic healthcare units [UBS] and a public health program cited as one of the ten best in the world, which is the Family Health Strategy. There are the community health agents, who live in the same district, earn a salary, and are responsible for the families under their jurisdiction. There’s also a nurse’s aide, a nurse, and a doctor. Today it covers just over 60% of the Brazilian population, but it should cover 100%. When a local resident has a problem, this team usually resolves it. It’s a bit like my experience in the prisons. There are no laboratories or X-ray machines there. Even so, I resolve about 90% of the cases myself.

That many?

Yes, with the basic drug kit available. Usually, the problems are simple. How often do we become seriously ill? Once or twice in our lives, in relatively normal people. Most of the time things get resolved in primary care. We know today that a hospital with less than 100 beds is technically and economically infeasible. But hospitals with 50 beds are the majority in Brazil. Building them is easy. Then you have to equip them and hire the doctors. That size of hospital will be very expensive for such a low patient-care capacity. It’s not feasible.

What is the solution?

Transform the small hospitals into outpatient centers. If there are 12 cities more or less close to each other, the biggest one is the one that should have a hospital with 100 beds or more, which all the municipalities should collaborate on, along with the state. Those who really need the hospital would go there. In general, we have a health structure that’s ready to go in Brazil. What does it need? In addition to organization, more money, because the total invested is small compared to what’s necessary.

How should healthcare be organized?

Brazil has no public health policy. In the last ten years, we’ve had twelve health ministers. This is because the position is political currency among the political parties. In state and municipal governments it’s the same thing. How do you organize and establish health policy under these conditions? In the ministry and in the state and municipal secretariats there are very competent people. When the Minister of Health goes down in Germany, he takes seven or eight assistants with him, who rise and fall with him. The minister’s role is to establish policies to direct the public health system. In Brazil, the minister brings a multitude of people into positions of trust, swaps out all the directors of local government and hospitals. Here, we can’t even show society the importance and relevance of SUS.

I love doing these projects on the internet, with texts and videos, because they reach an audience that’s inaccessible otherwise.

There isn’t another country in the world with more than 100 million inhabitants that has dared to offer free public healthcare to all. Not one. We are the only one. People don’t know this. When it comes to SUS, it’s often said: “It’s shameful, there’s gurneys in the hallway, children being attended to in chairs in the reception area.” This is because it’s not working at the primary care level. Just look at the lines at emergency rooms. If a doctor examines all these people, 80% to 90% will be released. They go there because they can’t get care at their UBS. At the emergency ward of the hospital, the patient knows that they will be taken care of, one way or another.

Most of these people are cared for by SUS.

SUS was the greatest revolution in Brazilian healthcare history. There is nothing comparable. I was a resident at the Hospital das Clínicas of the USP Medical School. At that time there was the INPS [the National Institute of Social Welfare]. Only workers with formal, registered employment were entitled to INPS benefits. Those who didn’t have this right were classified as indigent. It wasn’t a theoretical thing: it would be written on their medical record. The self-employed, and all the field workers, were dependent on society’s charity, such as the Santa Casa de Misericórdia [Holy House of Mercy, a centuries-old charity]. In 1988, they put in the Constitution: “Health is a right of all and a duty of the State.” Although I don’t like this slogan very much.

Why not?

First, it doesn’t say where the money comes from. Second, it infantilizes people. Taking care of one’s health is a duty of the citizen, primarily. This responsibility must be attributed correctly. When they fall ill and can’t treat themselves, patients can be treated by the state. In Brazil, everyone has this right. The system is hybrid, since we also have paid, supplementary healthcare. This system serves 47 million people, more or less. The rest, about 160 million people, depend on SUS. The investment of the private and public systems is around the same. The difference is that one serves 47 million and the other 160 million. Even if I have a private health plan, I can still be taken care of by the public system. In Chile, for example, you opt for one or the other. SUS is the largest income distribution program in the history of Brazil. The bolsa família (the federal Family Allowance) program is a timid project compared to SUS. A citizen may be living under a bridge and if he or she needs a liver transplant, they can get it at Hospital das Clínicas for free. How much would they spend in a private hospital? It’s a system that reduces social inequality. No one sees this other aspect of SUS.

How does your work as a writer happen? How do you prepare?

I read all the time. It’s much easier today; we take in information from every direction. I got more and more involved with writing. I wrote Estação Carandiru, which was published in 1999. When it came out, that book was number one on the bestseller list for four years, and has sold more than 500,000 copies to date. I think it had the merit of bringing the reality of a highly representative prison such as Carandiru out of the jailhouse for the first time, by a person who wasn’t involved in that world. That’s when I discovered a passion for writing. Journalism is also a very interesting exercise. You have to write within the allotted space, under deadline; you can’t be too fussy. And with a beginning, middle, and end. Unlike a book, where one wanders and often loses oneself in writing. Journalism gives you a goal, and I started to enjoy doing it.

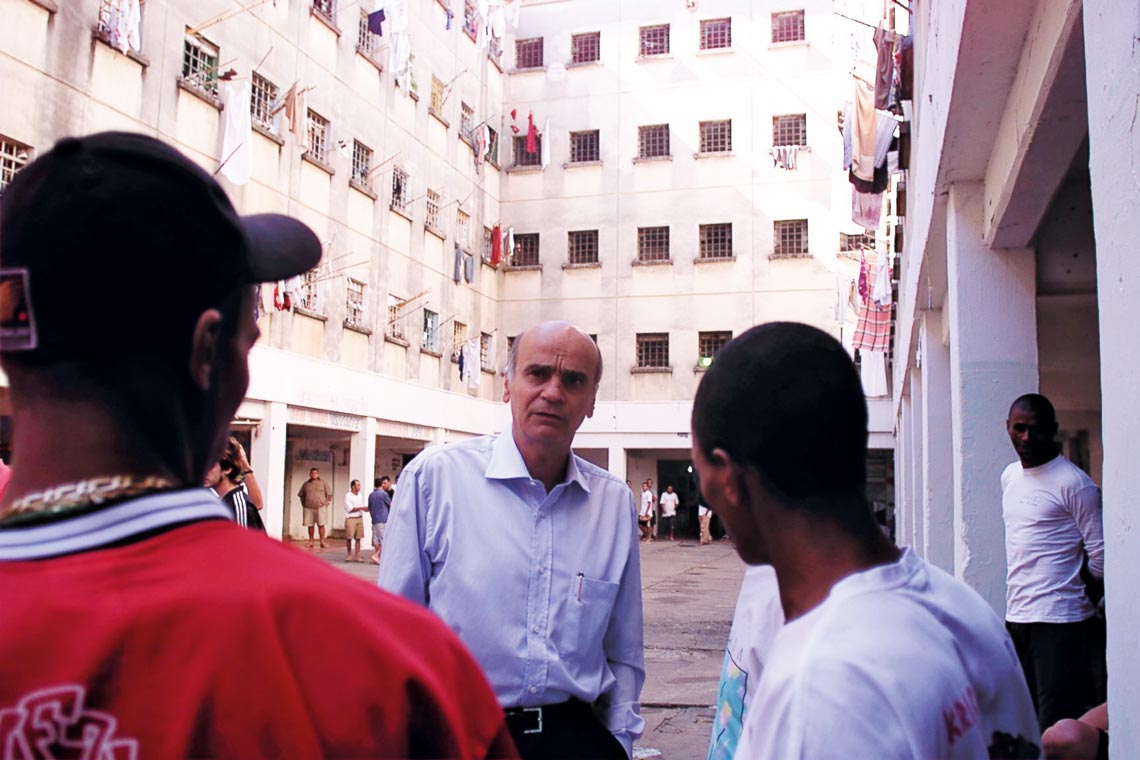

Caio Guatelli / Folhapress

In Carandiru, in 2001, with the rap group Comunidade Carcerária [Prison Community]Caio Guatelli / FolhapressDoes writing have a therapeutic effect for you?

Think about this: I sit facing a wall, with a computer, and I write. I have an idea, I sit there putting down words, and suddenly—sometimes this happens—I find a connection that works well in the text and I feel happy. And I obtained this happiness alone, staring at a white wall. Such happiness doesn’t exist in the world around us. With a little laptop in hand, one can arrive at that point. Once you have experienced that degree of happiness, you never stop writing.

So writing isn’t a long-suffering process?

For me it never was. On a Saturday morning, I go to the hospital, visit the sick, run back to the house, and write. It’s a huge pleasure. Before lunch I drink a cachaça to “maximize” the work… This I learned from the folks at Carandiru. Before cachaça I drank beer. Until one of them said: “Doctor, you have to drink cachaça because if you get drunk, they’ll say you’re a drinker. If you spend money drinking champagne, they’re going to say you’re a drinker. Beer, when it’s hot out, you drink one bottle, then another, and by the time you feel it you’ve already drank too much. With cachaça, you know who you’re dealing with.” It’s true, it’s easier to control.

With cachaça or without it, you became a writer…

I did follow that career path. I have my two columns, in the Folha de São Paulo newspaper and in CartaCapital magazine. For the internet, I take the text I write for Folha and summarize it in two minutes on YouTube, where I have a channel. Sometimes even in less time. When I take a look, 350,000 people have already watched. I have one video with almost 2 million views. It’s another world.

And they get a lot of comments…

It has everything. There are taboo subjects, like talking about abortion. It’s a matter of public health and not a religious question. When I talk about it, the responses are terrible. I’m 76 years old; I’m starting to see things with a closer horizon in mind. I can’t be worried about people cursing me out. We have to put forward ideas that have social relevance. Every time the ignorant take power, during dictatorships, for example, what do they do? The subtext is always “lower the culture.” At these times, the important thing is to maintain an open dialogue, a multiplicity of ideas. Self-censorship can’t take root.

Personal archive

During a meeting with prison guard friends in 2018Personal archiveDoes this also apply to taboo subjects?

I’m an atheist. The religious think and act as if they have a monopoly on human generosity. We know that there is generosity in chimpanzees and gorillas—who don’t pray. What is the basic principle of all religion? Belief, you have to believe. And what is the basic principle of science? You can’t believe in anything that hasn’t any experiments and results that can be reproduced. Only from that basis can we draw conclusions. Science is not the only way to see the world. There are other ways. But I don’t see how to reconcile these other worldviews because they are antagonistic.

Do you have a team that writes for the site and records videos?

There’s a group that started making recordings with me and set up their own agency, Uzumaki, which now provides services for the site. These languages change very quickly; we have to try to keep up. I love doing these projects on the internet because they reach an audience that’s inaccessible otherwise. The other day I was in a movie theater with my wife and there were some kids there. Suddenly, a girl placed her phone in front of my face with a photo: “Are you this guy here?” “I am,” I said. “Can we take a picture with you?” These are kids, 12 and 13 years old, who I can talk to using the internet, but not on television.

Are you working on a new book?

I am, but it’s still very early on. It’s basically about my memories, but the format isn’t well defined. I resisted it for a long time. It goes like this: we go about doing things in life and some work out, and some don’t. Many depended on myself, on my work, on some good decisions I made. Others no, they depended on opportunities.

You worry about turning chance events into personal merits…

Exactly. And when you appear on television, you become famous. Television is full of foolish people because the guy thinks that all that recognition is based on his personal merit. He doesn’t realize that if it were someone else the same thing would happen. It’s very mediocre to reach a mature age and still be looking at yourself in the mirror. There are other things that are more interesting.

Is there something you would like to have done and haven’t done yet?

When I got yellow fever I was 61 years old. There was a moment, technically, when I saw the exams, and I thought I was going to die. I thought, “What do you have left to do?” Well, there were lots of things to do. Now, at this point in my life, I’ve done everything I needed and wanted to do, but of course I can do more.