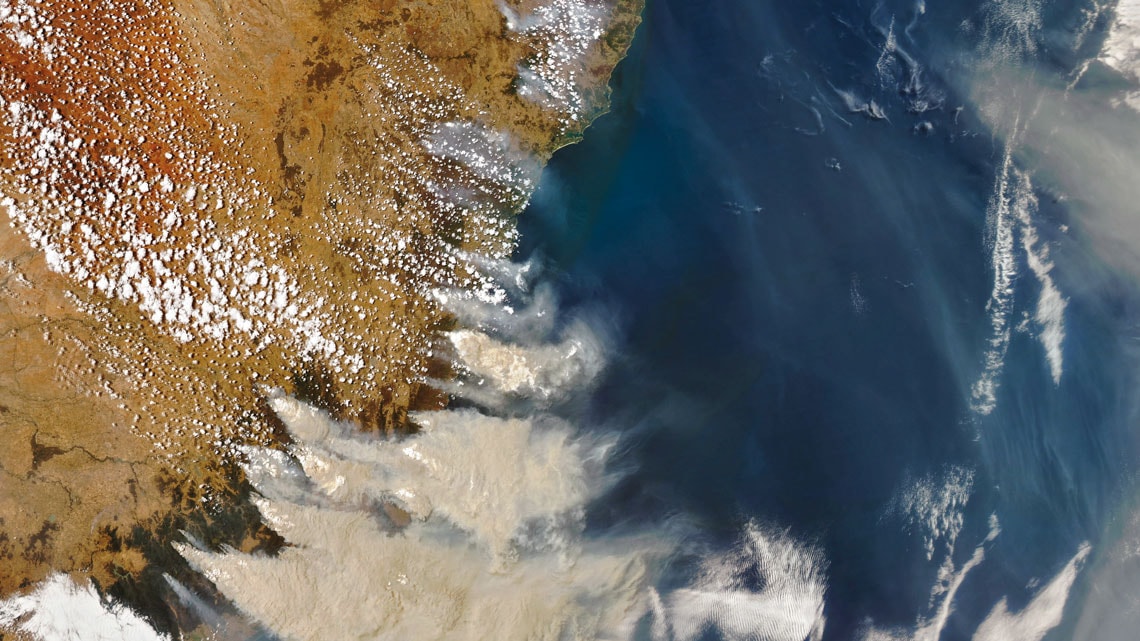

Australia’s forest fire season began in September 2019—months before expected—and has been one of the most devastating yet. The southern and eastern portions of the country, home to its two largest cities (Sydney and Melbourne), in addition to its capital, Canberra, were the most affected. By mid-January, when two days of heavy rain brought some relief to areas in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, hit the hardest by the fires, around 180,000 square kilometers (km2) of forest had been consumed by the flames. Over 2,600 homes and 6,000 buildings or facilities were destroyed, and 29 people died. It is estimated that 1 billion animals—not counting frogs and insects—have succumbed to the fires, including specimens of the unique Australian fauna, such as kangaroos, koalas, and wallabies.

The area affected by the fires in Australia in 2019 is more than 2.5 times the size of the forest-clearing fires in the Brazilian Amazon last year, when fires and resulting deforestation escalated in the northern region of the country. It is also larger than the areas of the Cerrado (wooded savanna)—the Brazilian biome most accustomed to fire—that burned last year, reaching 148,000 km2, nearly 75% more than in 2018. The damage in Australia may even increase, depending on weather conditions in January and February, historically considered the peak of the forest fire season.

There are more differences than similarities between the 2019 fires in Australia’s forests and those in the largest rainforest on the planet. Both fires released large amounts of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), due to the burning of plant biomass (trees, shrubs, and grasses), which stores a significant amount of carbon. In both cases, the global climate change scenario, which has gradually made large portions of Australia and the Amazon warmer and drier, seems to have created a backdrop that favors the occurrence and spread of fires during the months when droughts are longer and more intense. But the similarities end there.

Natural conditions in Australia hardly resemble those in the Amazon. “The situations are different. The Amazon boasts a rainy climate, which means that natural fires, usually caused by lightning, are an abnormality,” points out climatologist José Marengo, head of Research and Development at the Center for Natural Disasters Monitoring (CEMADEN). “In Australia, fires are part of the ecosystem and are necessary for its regeneration, much like what happens in the Cerrado, in Brazil. Although, of course, not at the abnormal levels seen last year.” In evolutionary terms, the plants that have developed in the Amazon are those that have adapted to very humid environments. Australia is the opposite, with the dominant species being those that thrive in dry environments, which are conducive to natural fires.

Brett Hemmings / Getty Images

Forest fire in November 2019 in Colo Heights, in the Australian state of New South Wales: 1 billion animals may have died in the fireBrett Hemmings / Getty ImagesDue to the high humidity, major natural fires are uncommon in the Amazon. Even if lightning strikes the forest during a drought, the spread of fires without human intervention is very rare. The average annual rainfall in the northern region of Brazil is over 2,000 millimeters (mm), and in some areas it is much higher. “In the Amazon, fires are generally linked to agricultural expansion and land occupation,” says meteorologist Luiz Augusto Machado, from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), who studies the process of rain formation in the region. “It is very unlikely that an electric discharge will cause and spread a fire in the rainforest.” In Australia, reports indicate that, during the current forest fire season, lightning from pyrocumulus clouds, which form over hot areas, such as forest fires or volcanoes, are helping spread and cause new fires in dry areas near the original fires.

While there are reports of arson arrests, Australia’s extended season of devastating fires is seen to be the result of extreme climate conditions caused by global warming. “There have been very large fires in the past, but they weren’t followed up with yet more very large fires a mere 15 years later. Normally, you’d be expecting a gap of 50 or 100 years [between major fires],” wrote David Bowman—director of the Fire Centre at the School of Natural Sciences at the University of Tasmania, Australia—in early January, on the science outreach website The Conversation. In February and March of 2009, for example, there were major forest fires in the state of Victoria that caused the deaths of 179 people and the loss of 4,000 buildings. “So, ecology is telling us that the intervals between the fires are shrinking. That is a really big warning sign. The whole system is moving to a world that is hotter, drier, and with more frequent fire activity. It’s what was forecast and it’s what is now happening,” said Bowman.

Eucalyptus trees on fire

From the time when Aboriginal peoples occupied the Australian territory, thousands of years ago, fire has been used sparingly, usually in the beginning of the dry season, to help regenerate the vegetation and clear land for farming. Small controlled fires, for example, reduce competition from established plants and create ash beds suitable for the growth of new plants. About 75% of Australia’s forests are made up of eucalyptus trees, native to the country, whose evolutionary history points to a close relationship with fire-prone environments. Eucalyptus trees, and some plants from the Proteaceae family, have robust underground systems, ready to sprout quickly after their trunks and branches are burned.

“There is good fire and bad fire,” explains forest engineer Giselda Durigan, from the Laboratory of Ecology and Hydrology at the São Paulo Forestry Institute, who studies the ecological processes of the Cerrado and the Atlantic Forest. “Sometimes fires are necessary for fire-adapted systems.” Durigan points out, however, that the current fires in Australia are due to extreme climate conditions, which far exceed historical averages that kept the balance in the ecosystems. “It is very difficult to control forest fires when there is prolonged drought, high temperatures, and strong winds,” claims the researcher, who visited northern Australia last year, before the fires began.

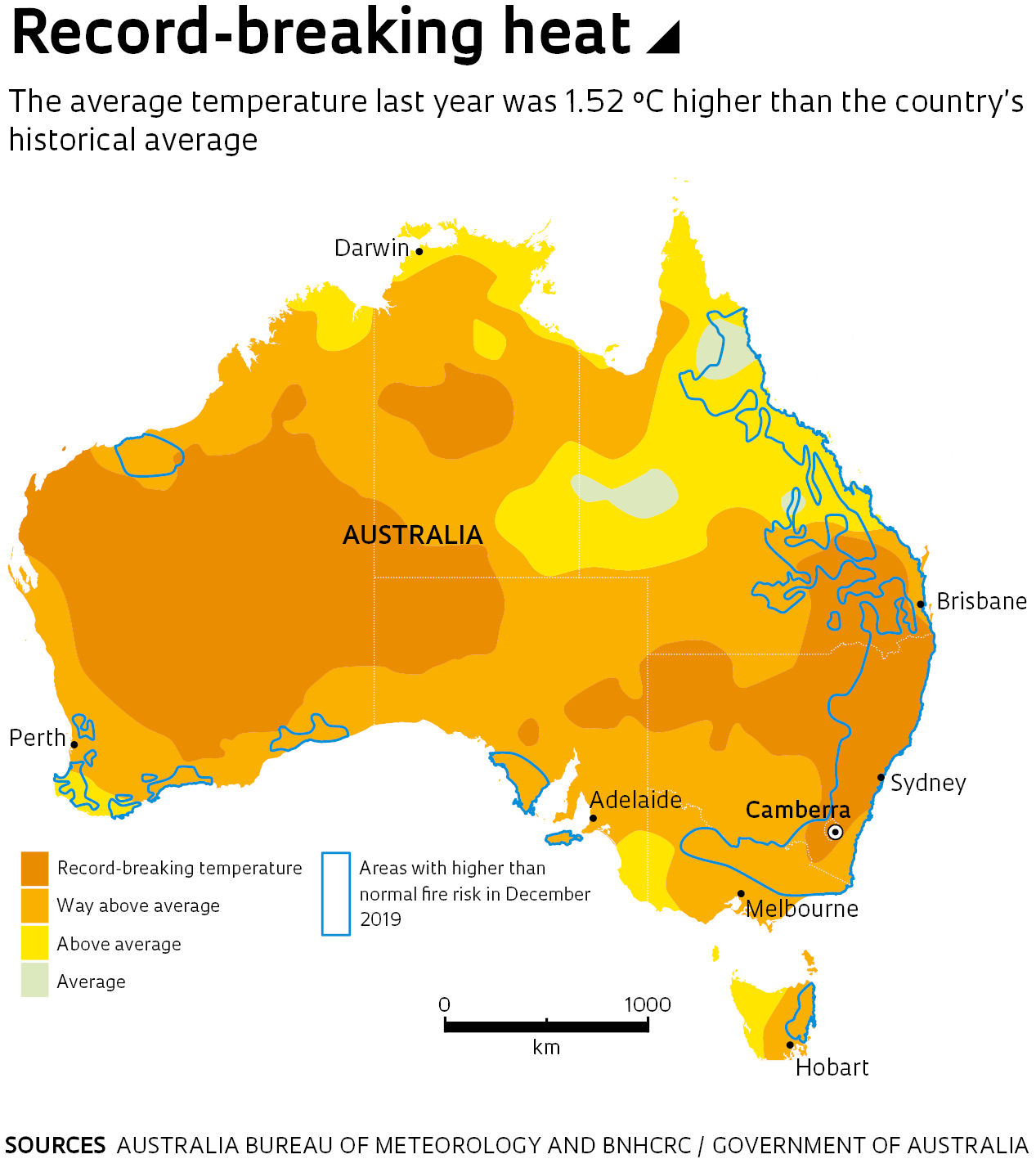

Except for Antarctica, Australia is the continent with the lowest rainfall rates on the planet. According to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, 2019 was the driest and warmest year in the former British penal colony since 1900, when systematic records of climate data began. Experts associate these unprecedented climate extremes with Australia’s current extended fire season. In 2019, rainfall rates averaged 277 mm, 40% less than the average for the period between 1961 and 1990. Until then, 1902 had been the driest year, with rainfall of 314.5 mm. Rainfall rates in New South Wales, home to Sydney, the most populous city in Australia, only reached 250 mm last year, a record-breaking low for the state.

The average temperature in the country was 1.52 ºC higher than the historical mark, and the average maximum temperature exceeded the historical average by 2 ºC. “Observations indicate that extreme climate conditions favorable to forest fires are likely to become more frequent in the summer, and the burning season tends to start earlier, especially in southern and eastern Australia,” says climatologist Lisa Alexander, from the University of New South Wales Climate Change Research Centre, in Sydney. “This escalation is due to the action of human beings, but that does not mean that the natural climate variability from year to year has played no role in the current fire season.”

Globally, 2019 was the second hottest year on the planet, after 2016. Ironically, despite so much drought and heat, for some northern areas in the state of Queensland, located in northeastern Australia, 2019 saw record rainfall rates throughout the year, basically due to major storms recorded between January and February of last year. But much of Queensland suffered from drought, heat, and fires throughout the year.

With a population of just 25 million, Australia is a continental country, slightly smaller than Brazil, with the Indian Ocean to the west and the Pacific Ocean to the east. Due to its geographical position, the temperature of ocean waters greatly influences its rainfall rates. Two non-periodic oceanographic phenomena affect the Australian climate: El Niño, which is the abnormal warming of the Pacific waters, and the Indian Ocean Dipole, or the difference between water temperatures at the western portion of the Indian Ocean (closer to Africa) and its eastern portion (near Australia). El Niño—an anomaly that also affects the climate in South America, including Brazil—did not occur in 2019. But the Indian Ocean Dipole, a phenomenon discovered only in 1999, had one of its most intense positive phases ever recorded.

The so-called positive phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole occurs when the waters are warmer on the western side than on the eastern. In climactic terms, this results in less rainfall in central and southern Australia, increasing the risk of forest fires. In the past, the positive phase was identified as occurring from May until mid-November. During the second week of October, the surface waters of the Indian Ocean adjacent to Australia were 2.15 ºC cooler than the waters near Africa—a historic record. Up until then, the highest difference (1.48 ºC) had been observed in the beginning of November 2006.

Regardless of how the Australian fires originated, the country debates the role of the federal government in preventing and combating fires. Skeptical of climate change and of sustainability measures for the economy, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison has been the target of criticism, as the country that is home to eucalyptus trees and kangaroos is also the largest global exporter of coal, the use of which greatly increases greenhouse gas emissions.

Republish