At the turn of the twentieth century, a doctor from Pernambuco followed a path similar to that of others seeking innovative treatments for psychological disorders, like the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) in Europe. Antônio Austregésilo Rodrigues Lima (1876–1960), a neurologist and psychiatrist from Brazil, who often signed his works simply as Antônio Austregésilo, delved into what would later evolve into psychotherapy. He made significant theoretical contributions to psychoanalysis, including refining the diagnosis of hysteria, which at the time was commonly associated with women, and distinguishing it from other psychological and physical conditions.

As a sexologist, Austregésilo was keen to understand the intricacies of Rio de Janeiro’s nightlife. “He visited cabarets, spoke to prostitutes, and took an interest in life as it was,” says psychiatrist Paulo Dalgalarrondo from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), one of the authors of an article about Austregésilo published in July 2020 in the Latin American Journal of Fundamental Psychopathology.

Austregésilo authored books written in accessible language on sexuality, such as Neurastenia sexual e seu tratamento (Sexual neurasthenia and its treatment; 1919) and Conduta sexual (Sexual conduct; 1939). In these works, he proposed sex education as a means to address what he viewed as deviations in sexuality, including homosexuality. He championed a candid, non-hypocritical approach to sexuality in schools and advocated for the broad dissemination of sexology among students—a stance that continues to stir discomfort in more conservative sectors of Brazilian society.

Family’s Collection Austregésilo in the traditional uniform of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, to which he was elected in 1914Family’s Collection

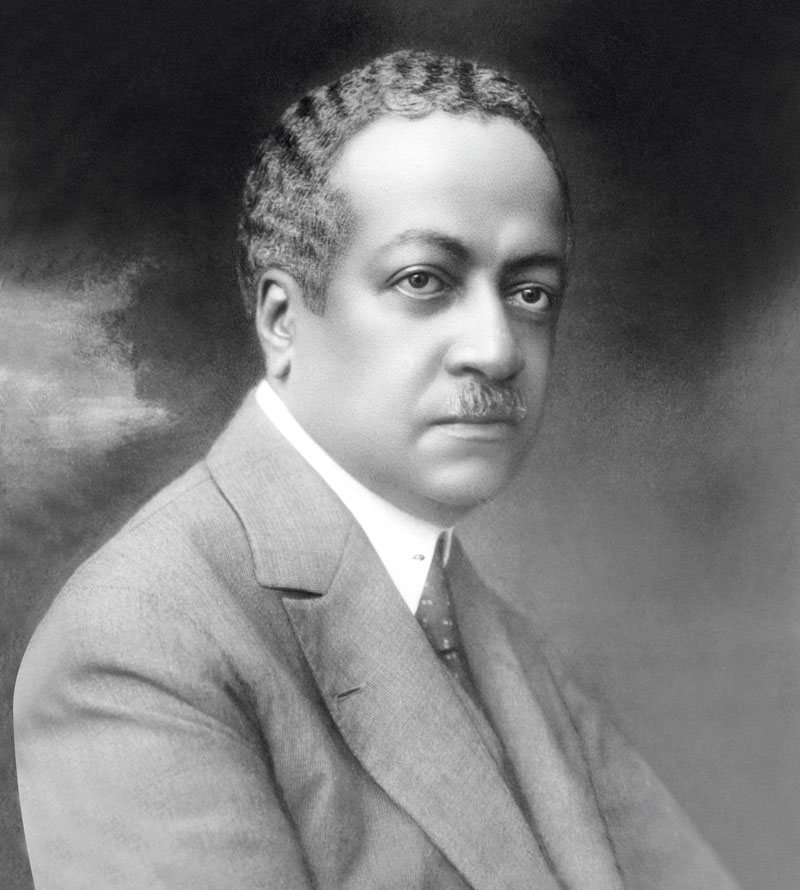

Austregésilo was of mixed-race descent and, unlike many other Afro-descendants, had the opportunity to pursue his studies—his father was a lawyer. At 16, he moved from Recife to Rio de Janeiro to study medicine. His interest in mental disorders became evident in 1899 with his final thesis, Estudo clínico do delírio (Clinical study of delirium). In the following decade, he joined the team of the prominent Black psychiatrist Juliano Moreira (1872–1933), who ran the Hospício Nacional de Alienados from 1903 to 1930. Established in 1852, this was Brazil’s first psychiatric hospital, located in Rio de Janeiro (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 124 and 263).

One of the pioneers of psychiatry in Brazil and a founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, which he chaired from 1926 to 1929, Moreira abolished the use of straitjackets, removed bars from patients’ room windows, created spaces for dialogue with those being treated, and separated adults from children. He and Austregésilo were convinced of psychiatry’s disciplinary and moralizing role. They advocated for hygienism, which promoted the sanitation of cities to prevent epidemics, and recommended mental and physical hygiene as a means of preventing mental disorders.

Austregésilo also engaged with eugenics, a strategy aimed at improving the human species by sterilizing individuals deemed unfit, such as those with hereditary diseases, or by preventing the reproduction of so-called inferior races. In Conduta sexual, he supported the penal sterilization of repeat offenders but opposed the racist views of São Paulo doctor Renato Kehl (1889–1974), who founded the São Paulo Eugenics Society and attributed mental disorders to skin color.

National Archive / Wikimedia CommonsJuliano Moreira, director of the Hospício Nacional de Alienados from 1903 to 1930National Archive / Wikimedia Commons

Critic of freud

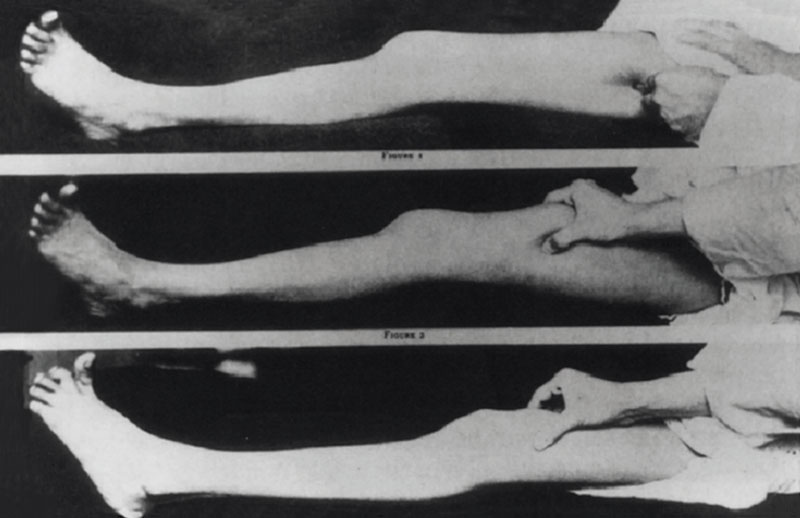

In 1912, Austregésilo became the first professor of the newly created chair of neurology at the National Faculty of Medicine, which later integrated into the University of Rio de Janeiro, now the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). That year, alongside his student Faustino Esposel (1888–1931), he published an article in the French psychiatric journal L’Encéphale on a symptom that had not yet been described in relation to damage to the corticospinal tract. This bundle of axons, the extensions of neurons, transmits signals from the cerebral cortex to the spinal cord and controls voluntary movements. The so-called Austregésilo-Esposel sign consists of pressure applied to the muscles and nerves in the central region of the thigh, which causes the big toe to rise and the neighboring toes to fan out. This sign can indicate damage to the spinal cord or brain.

Another pioneering work, published in 1928 in the Revue Neurologique, this time with fellow neurologist and compatriot Aluízio Marques (1902–1965), was the description of the first case of post-traumatic dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions). This case involved a 25-year-old patient who had experienced the symptom since the age of 13, resulting from head trauma caused by falling from a streetcar.

Austregésilo visited medical research centers in Europe and the United States and represented Brazil at international neurology congresses. One of the studies he supervised at the Faculty of Medicine in Rio was that of Genserico Aragão de Souza Pinto (1888–1958), from Ceará, whose final thesis, defended in 1914, was the first academic work on psychoanalysis in Brazil.

Elected in 1914 to the Brazilian Academy of Letters (ABL), Austregésilo wrote 35 books. In his inaugural speech, he warned of “the tendency towards exaggerated mimicry of things from the Old World” in Brazilian intellectual circles, a tendency that, according to him, reflected a certain “disdain for our original qualities.” Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Silvia Alexim Nunes concurs: “Brazilian psychiatry was very imported.”

National Archive / Wikimedia CommonsHospício Nacional de Alienados, the first psychiatric hospital in Brazil, between 1859 and 1861National Archive / Wikimedia Commons

His body of work includes psychoanalytical writings and literary essays. “He was read by a more educated audience, including doctors, teachers, lawyers, engineers, and civil servants,” says Dalgalarrondo from UNICAMP.

In two books published in 1916, Pequenos males (Little evils) and A cura dos nervosos (Cure for the nervous), Austregésilo advocated for the use of dialogue to treat mental disorders. “He relied on a therapy based on persuasion, on the idea that the patient could be convinced to correct what was considered an error in thinking through conversations with the therapist,” explains psychologist Mikael Almeida Corrêa, from the Federal University of Rio Grande (FURG) and author of an article on Austregésilo’s early works published in June 2024 in the Revista Brasileira de História da Ciência.

Corrêa suggests that this method was a precursor to today’s cognitive-behavioral therapies, developed by Swiss neuropathologist Paul Charles Dubois (1848–1918). In this approach, conditions such as hypochondria, anxiety, panic, and phobias were treated by reeducating the mind and body.

Austregésilo considered psychoanalytic theory, which was beginning to gain ground in Brazil at the turn of the twentieth century, to be just one of several interesting alternatives for treating psychological disorders. His critical eye led him to develop an approach similar to Freud’s theory of the human mind. For the Austrian doctor, the psyche can be understood as the interaction between the id (the unconscious, where libido resides, formed by desires and instincts), the ego (the basis of the conscious personality, which adjusts to desires), and the superego (the aspect of the personality shaped by morals and the repression of desires).

Austregésilo, A. E ESPOSEL, F. L’Encéphale.Austregésilo-Esposel sign: toe reflex indicates neurological alterationAustregésilo, A. E ESPOSEL, F. L’Encéphale.

The doctor from Pernambuco proposed an alternative structure, composed of what he called fames (hunger, in Latin), libido, and ego. Fames corresponds to the most basic survival needs, particularly related to nutrition, which he described as the “inner force of living matter” in his 1938 book Fames, Libido, Ego. He viewed libido as specifically linked to sexual desire, in contrast to Freud’s broader interpretation of libido as motivating desires beyond just sexual needs. Finally, Austregésilo saw the ego as the structure that integrates these two fundamental motivations.

In the same 1938 book, while acknowledging what he considered “Freud’s genius vision,” Austregésilo critiqued psychoanalysis, which he referred to as “dogmatic doctrines.” According to him, Freudians believed that everything could be explained through the psychoanalytic framework of the “sage of Vienna.” He also expressed reservations about the supposed dominant role of the libido in psychic disorders: “I fully agree that in the human species the libido plays a very prominent role in the origin of neuropsychoses, but I am not an exclusivist as Freud and his supporters want me to be.”

In an article on the state of the art of psychiatry, published in 1945 in the Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana, he wrote: “Body and spirit form a physiopathological unity. The clinician must always bear in mind that there are psychic roots in organic illnesses, just as there are often organic elements in functional illnesses.”

His criticisms, however, did not have a lasting impact among Brazilian psychoanalysts in the mid-twentieth century. According to Nunes, the hygienists, including Austregésilo, adapted what they found useful in psychoanalysis—the idea of the unconscious and the possibility of accessing it—in a moralizing and pedagogical context, aimed at correcting behavior. This approach, however, diverged from the core goals of Freudian psychoanalysis.

Family’s Collection Austregésilo (featured) and the medical team in front of the women’s clinic, between 1900 and 1920Family’s Collection

False hysteria

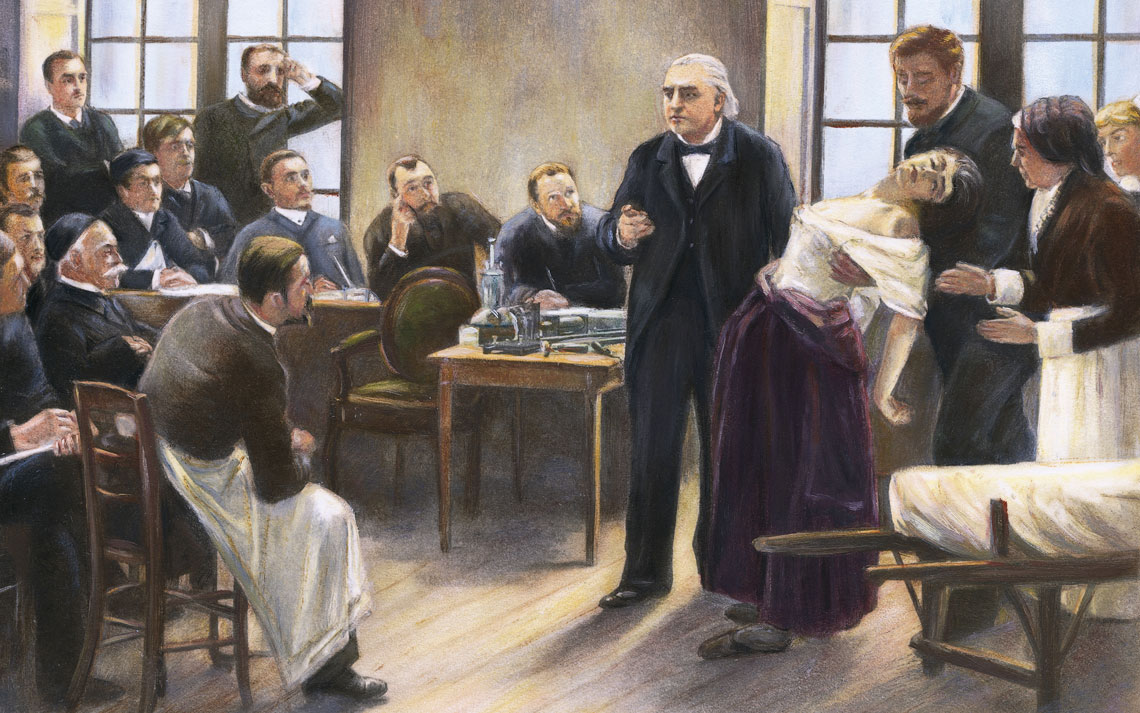

One disorder that received significant attention from psychiatrists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was hysteria. Typically characterized by psychological crises, fainting, and tremors, hysteria had long been seen as a condition specific to women—hysteros being the Greek word for uterus. In the nineteenth century, diagnoses of hysteria were often used as a tool for medical control and for disciplining the female body, leading to a wave of hospitalizations for women whose behavior did not align with the expectations of wife and mother according to prevailing social norms. By the early twentieth century, while hysteria was attributed to neurological or psychological causes rather than being linked to the female reproductive system, the condition was still strongly associated with women. Moreover, the diagnoses were often imprecise.

Dissatisfied with these inaccurate assessments, Austregésilo distinguished between hysteria and hysteroid syndrome, or pseudo-hysteria, arguing that many cases previously thought to be hysteria were, in fact, the result of other physical or psychological conditions, such as early dementia, brain tumors, or alcohol intoxication. “He cleared the field and made hysteria diagnoses more accurate,” says Nunes. “In this, he was successful and very influential.” According to Nunes, Austregésilo did not follow the prevailing trend of psychiatrists who characterized women showing signs of hysteria as degenerate, although he was still committed to the hygienist ideal of educating individuals toward behaviors that conformed to societal morals.

Dalgalarrondo notes that Austregésilo approached the study of the relationship between infectious diseases, such as syphilis, and the psychological alterations associated with them—such as neurosyphilis (an infection of the central nervous system)—with great rigor. The exact nature of the mental alterations, whether a direct effect of the pathogen or an indirect result of an imbalance in the body’s defenses, remained unclear. “Although he didn’t have current knowledge, he wasn’t simple-minded, as one might suppose, and was aware of the high complexity of the causal relationships being investigated,” says the UNICAMP psychiatrist.

Austregésilo was elected deputy for Pernambuco in 1921, and was reelected three times, holding office until the 1930 Revolution. While researching the history of the House of Brazil in the University City of Paris, inaugurated in 1959, historian Angélica Muller from Fluminense Federal University (UFF) discovered an earlier design for the building that highlighted the prestige of the Pernambuco doctor.

In 1926, Austregésilo traveled to France to mediate diplomatic negotiations for the construction of a building to house Brazilian students in Paris. “When he returned, he proposed a bill calling for the creation of a Brazilian student house in the French capital,” says Muller. The bill was approved that same year, with funding sanctioned by then-president Washington Luís (1869–1957). However, when Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954) came to power in 1930, the project was abandoned. The idea of building the House of Brazil in Paris was only revived in a different form in the 1950s.

The story above was published with the title “In Freud’s shadow” in issue 347 of january/2025.

Scientific articles

AUSTREGÉSILO, A. Os progressos da psiquiatria. Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. Vol. 24, no. 12. Dec. 1945.

CORREA, M. A. Havia um “Freud brasileiro”? Notas biográficas e análise teórica das primeiras obras de Antônio Austregésilo. Revista Brasileira de História da Ciência. Vol. 17, no. 1. pp. 325–44. Jan.–June. 2024.

DALGALARRONDO, P. et al. Das psicoses associadas a infecções no Brasil: 100 anos da contribuição psicopatológica de Antônio Austregésilo. Revista Latino-americana de Psicopatologia Fundamental. Vol. 23, no. 3. July–Sept. 2020.

NUNES, S. A. Histeria e psiquiatria no Brasil da Primeira República. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos. Vol. 17, sup. 2. pp. 373–89. Dec. 2010.