MIGUEL BOYANANMaterial sent to Cemel: Technology and a little bit of luck helps in identificationMIGUEL BOYANAN

The 30th of June of 1999 marked a change in the paradigm of Brazilian legal medicine. On that date, in the town of Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo State, the Legal Medicine Center (Cemel) started to operate. The main difference from other centers is the fact that it is installed in a university campus – in this case that of the University of São Paulo (USP) -, along with the Service for the Verification of Deaths in the Interior (SVOI) and the town’s Medical-Legal Examinations Center (NPML) was also transferred to the site.

The research carried out at the university is thus extended to the IML (Legal Medical Institute), a rare fact in the history of Brazilian medicine. The creator of the center, Carmen Cinira Santos Martin, a professor at the Pathology Department of the Medical School, had been fighting for almost eighteen years to take this specialty out of the limbo. Her interest goes beyond having an improved building other than the decrepit and austere morgue of the town. “I wanted to improve the teaching of the discipline of forensic medicine and to turn it into something as good as that what exists in the world”, Carmen explains.

She has not managed to do that yet. But today, four years after its inauguration, Carmen is beginning to receive the returns from the attention that she has dedicated to the center and to forensic medicine. The edition of the 1st of May ofNature had two pages describing the work being carried out at the Cemel. The magazine took an interest in this distant center of a developing country when it got to know of the work of Marco Aurélio Guimarães, a young Brazilian researcher at Cemel who took his post-doctorate thesis at Sheffield University in Britain. Guimarães extracted DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) from the bone and teeth of old bones, something difficult to manage even for the best laboratories in the world.

Carmen is collecting other fruits of her perseverance. The Cemel Center is a reference for Brazilian towns and she is constantly invited to give talks at all ends of the country in order to explain how she attained this legal medicine working system. The model of the center, a building of some 1,200 m2 , which today runs with thirty employees (including those of the IML and the SVOI), also serves as an inspiration for the Public Health System (SUS), which already has ready a minute on the law concerning questions on the verification of the cause of death. In the following interview, Carmen explains the reason behind this success.

How did the magazine Nature discover your work?

The researcher Marco Aurélio Guimarães did his post-doctorate phase at Sheffield University in Britain, carrying out examinations on the DNA of bones from European archeological sites. The results were excellent. Afterwards he applied the same technique on material sent from Brazil. The results were also very interesting and published in the local press in the United Kingdom. Nature got to know and contacted Marco Aurélio to get a better understanding of the identified cases. The exchange of information between the reporter from Nature, David Adam, and the researcher, resulted in the interest of the magazine in knowing at first hand legal medicine at the Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, the material from Brazil that had been researched and the person responsible for it. We are talking about Professor Daniel Muñoz from the Medicine School of USP in São Paulo, who was the first person to be interviewed by the English magazine and who spoke of his work regarding the identification of people who had disappeared during the military regime.

Was the story done here?

Marco Aurélio returned in December to Ribeirão Preto and kept exchanging e-mails with the reporter from Nature. He told him that he had been working at an emergent center of legal medicine, but that our country had immense difficulties in this area. Then the reporter came here in February and stayed for two days with us, getting to know the location and asking about everything.

You yourself are from Rio de Janeiro. How did you come to work at Ribeirão Preto?

I came here for my post-graduate thesis. I studied medicine at the University of Brasilia, back at the beginning of the 70’s. I completed the course and did my residency in pathology. Then, during the third year I wanted to quit medicine, as I didn’t like having to deal with sick people. At that point one of my professors said: “OK, go and work with the dead.” I thought it was an excellent idea and during my fourth year I was already starting to train in legal medicine. Since then, I’ve never left the area. When I completed my residency, I wanted to teach, following a family trend. And I wanted to give lessons on violence, a subject that fascinated me. I chose Ribeirão Preto because it ran one of the best post-graduation courses in pathology in Brazil. In fact, it was not the best, it was the second best. However the first one, in Salvador, I couldn’t enter. I went there, made my application, but since I was the only candidate during that year I wasn’t accepted.

You yourself wanted to have a teaching career in what exactly?

In what I could do, which was pathology. I was a pathologist, but had an interest in forensic medicine. I chose pathology because it involves working with the body. It was the only way of learning to deal well with the question, in order to later to apply that learning in questions of violence. Since there was no master’s, doctorate, or medical residency in legal medicine, nor even a short specialization course in the universities, I opted for my post-graduation in pathology. In truth, I could have applied for entry into the police force, which is where the coroners learn in Brazil, but I didn’t want to get myself involved in the Police Academy. In Ribeirão Preto, all the professors interviewed me to see if they would accept me as a post-graduate. I was clear: I stated that I had not enjoyed pathology, but liked legal medicine. To which they asked: “What then are you doing here?” But one of them who ended up being my supervisor for my master’s and doctorate, Professor José Alberto Melo de Oliveira, looked through my résumé and asked: “Wait a minute, you really like legal medicine?” I confirmed it and he helped me. I ended up doing my master’s and doctorate on questions dealing with legal medicine within the Pathology Department.

Now, so many years afterwards, you intend to set up first forensic pathology course. How is it going to be?

In Brazil, medical residency in functioning legal medicine does not as yet exist. We intend to make a bridge between pathology and legal medicine at the Medical School here in Ribeirão Preto, creating a four-year residency course in forensic pathology, which is part of legal medicine. We’re in negotiations with the Pathology Department.

So, the master’s and doctorate courses in legal medicine are going to be on forensic pathology, which is none other than part of legal medicine, correct?

That’s correct. I do not want to leave the Pathology Department which is excellent. It’s simply a question of nomenclature, who wants to work, works independently from the name of the specialty.

Why has there always been difficulties in the teaching of legal medicine in Brazil?

In the first place, the formation of a legal doctor does not exist. Any medical doctor, with any background, can today take the course to be a legal doctor. He takes the course by merely reading theory. In the Police Academy – I’m speaking about the State of São Paulo -, these candidates are trained during approximately one month. They have to leave everything, family, other things to do, etc. Many of them give up. After this training, they begin their professional activity carrying out examinations in the morgue and looking at body wounds of people who are alive.

What they are learning to do is merely impressionist work? Only describing what they see, as any other person would do?

That’s more or less it. It’s not surprising that the quality of legal medicine in Brazil is extremely poor. It’s only good on the occasion when the individual who is doing it is a very good professional through his/her own merit.

The Nina Rodrigues Institute in Salvador, where you yourself wanted to go, is it also the same?

It is more or less the same, as it is throughout Brazil. The difference is that in Salvador there is a more open environment. Within the building of the Nina Rodrigues Institute I was even inspired to think about things here. The institute there was better in days gone by. But, still it is the best structure Brazil because the person who constructed the building, Professor Maria Teresa Pacheco, is a visionary. She built a beautiful building of 5,000 m2 . At the time of building, the university was together with the IML, which led to legal medicine advancing at the university. When it’s together it works well. When it’s separated the quality falls through lack of research.

You inspired yourself on what centers in order to create the Medical-Legal Center (Cemel)?

Portugal has a model that I consider to be ideal. But in Brazil, Salvador and Brasilia also have major importance because they are more open. As a student, one could go to the Medical-Legal Institute and can walk through the building at will. This was during the military regime. These things only happened because the university opened up space. Maria Teresa Pacheco, today a retired professor, allowed the student in Salvador to see legal medicine from the inside and not only in theory. In Brasilia it was the same thing.

Why is the model for the Cemel different?

Because we invited the IML to come to the university and we can work together, mainly in research. Today we already have four legal medical doctors from Ribeirão Preto who have concluded or are concluding their post graduation and their research was motivated by the work carried out together. This is a huge difference. This was made possible by researchers at the Medical School of Ribeirão Preto. Who had the courage to sign a check for R$ 600,000 for the creation of this center was Professor José Antunes Rodrigues, who is one of the best researchers that we have, and is an ex-director of the college.

How did this process come about?

One day, back in 1996, I spoke to Professor Antunes and told him that I had been at this school for nearly fifteen years and had never taken a student to the mortuary of the IML in Ribeirão. And that I never would. The IML had a terrible room; small extremely ugly and poorly prepared. Legal medicine already dealt with everything in a sad manner, everything ugly – ugly for others, for me it is beautiful – and I could not take a student who had been thinking in taking up another specialty to a place like this. I wanted to bring students into legal medicine, seduce them with my specialty and not frighten them. If one was to take them to the mortuary, they would never again wish to know about legal medicine. I spent eighteen years giving lessons using models. I even said to them: “If you want to go to the IML in Ribeirão, you can go, but I’m not going to take you there”. I said to Professor Antunes that I was not going to continue working in that manner, that I was going to do other things, and he ended up by taking over the Cemel project.

Why did Portugal serve as inspiration?

There, obliged by federal law, a university professor has to be the director of the IML. It is a much more advance system than ours. The director cannot have a police career. One doesn’t have the police in the middle, because the coroner is affiliated not to the Secretary of Public Security, but to the Secretary of Justice. Dealing with magistracy is another level. There is no police commissioner in the middle. The Portuguese researcher Nuno Rodrigues, from the University of Coimbra, a specialist in legal medicine, of worldwide renown, whenever he comes to Brazil says in his lectures that it is not possible to agree with the Brazilian system, in which the machine that punishes is the one that investigates. He is also a member of Amnesty International.

This model from Portugal is similar to that in the United Kingdom and the United States?

I have copied the American model in one sense and the Portuguese model in another. In terms of administration I copied the Portuguese. In the United States, the university is not necessarily working hand in hand with the IML. For example, I know very well the people from Colorado in the United States. The head of the IML service is not a university professor, but has taken a course in pathology. There lies the basis for all: he is a pathologist in the first place. Afterwards he went on to do forensic pathology. This is the good part of the American, British and Canadian models. However, the administration of them is not as good as that in Portugal because the IML does not work in conjunction with the university.

Why is the system better when it is headed by a professor?

Because of the university. The professor values research.

But is it not a problem when the best university teams also turn themselves into bureaucratic teams?

The professor of legal medicine does not carry out research in this area if he is not aware of what is going on within the IML. This is the big issue that people do not understand. In the IMLs there are competent professionals, but if they are not trained in research, they are going to work in a limited manner. I am together with the IML but I don’t run the IML. Although the administrative post should really be one of value, it is necessary that someone is available to create research groups in locations where there is teaching and assistance and scientific investigation doesn’t occur as it should. Today I run two administrations. I administer the Cemel because it belongs to USP. The other administration, temporarily, is that of the Service for the Verification of Deaths in the Interior (SVOI), which is a unit of USP.

Is it an advantage to have your IML colleagues here within?

It is because it makes all of our work easier. It is similar to the model in use by the Americans. The American does the same thing only with a better base because the doctor that verifies death is the same person who examines violent death.

Does the formation of coroners in Portugal involve the same thing?

No, in Portugal it isn’t so good. In the other countries, the formation of the coroner is in forensic pathology. In Portugal, I have found this large error, or that is to say, the coroner also carries out the verification of death without being a pathologist.

Why was the law of 9th of February of 1998, published by ex-Governor Mário Covas, so important for your people?

The previous law to this one stated that the coroner was subordinate to the police commissioner. Who headed the coroner’s office was the police. Governor Mário Covas put in the place of the police commissioner a criminal examiner or coroner. This position, in the Covas law, is that of the Director of Technical Police. In each administration, there will be a medical or a non-medical investigation.

What is the Public Policies Project, financed by FAPESP, like?

This was the second Cemel Project. The idea is to pass technology and training to the people at the IML of Ribeirão Preto and those at the SVOI. When we began the work here daily, the lawyers contested the results on the blood alcohol levels because the methodology was inadequate. It was at that point that I considered that Bruno Martinis, a very well trained researcher, already developing a project at the Cemel (under FAPESP’s Young Investigator program), could take over the toxicology laboratory. The Public Policies Project, which is entering into its second phase, has as its objective the training of technical people in the participating institutions to take samples for blood alcohol levels, which is the examination most in demand. There are a few very basic procedures such as, for example, teaching that there are the appropriate receptacles for collecting blood. Once certified that the training occurs adequately, the proponent institution, which is the Medical School, has the responsibility of transferring the sophisticated technology on the use of chromatography, the equipment that processes the blood sample. The final hoped for result is the efficiency of the procedures and the certainty of trustworthy results.

Or that is to say, you had a problem of the lack of technology and training?

The best piece of equipment in the hands of untrained technicians does not produce results. When I said that the work is elementary, it is because we had to instruct on how to collect, guard and place in the fridge, etc. Today the scenario has completely altered and things are much easier. The project, financed by FAPESP, is important because it is not possible to imagine, in the times during which we are living, that we had still not gotten over these basic problems. To have good equipment and well-trained technicians is a guarantee for the community.

What is the laboratory project on DNA that is going to function at the Cemel all about?

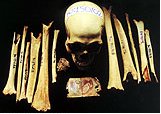

The laboratory will be important when we don’t manage to carry out legal dental identification, or via a prosthesis, or by the absence of a limb. In the region of Ribeirão Preto it’s very common to find bones during the collection of the sugarcane. The sugarcane field is a place often used to hide bodies because the sugarcane, even when small, easily covers the body, which will then only be discovered when the plant is being harvested. The laboratory will help when families reclaim the bodies and the common methods of identification are not enough to settle the question. At that point, the DNA examination of the bones comes into play. The project is ready, but laboratory equipment is missing. The problem is not to set up the laboratory. No, the most difficult thing is to know how to do. And this Marco Aurélio Guimarães knows. Furthermore, he has the legal-medical background. This is important.

And how can your people help to identify the bones suspected of being those of who disappeared during the military regime and were found in the Dom Bosco Cemetery in São Paulo?

There isn’t just one single method of identification. Today one only hears of DNA, it seems that only this method exists. But this is not so. The easiest method, the best of them all is the legal dental identification. If you have a worked on dental arch that has amalgams and resins that are registered, then it’s easy to identify the bone. The same thing occurs with prosthesis. I have had here a few dozen identifications done in this manner. There is then no way to have any doubt. It’s not possible for a medical surgeon to place a prosthesis in your leg and in mine and for them to be the same, so many are the variables. We are going to help in this identification by way of the DNA exam when we’re asked.

Who finances the Cemel? Is it USP?

USP pays a large part. This building cost R$ 600,000, paid for by the Medical School in order to have a discipline of legal medicine. The money comes from USP, but comes out of the budget for the Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, we don’t ask for a special allocation from the university. In order to pay expenses such as cleaning material, for example, there’s another source, also from USP, which is that of the SVOI, a university unit that’s housed here because it’s coupled to the Pathology Department. This service has the salary payments for everyone who works here paid by USP and a part by the Secretary of Public Security. At present the maintenance budget is very small that comes from the SVOI. Per month there’s a total of R$ 4,489.00 to purchase cleaning material and to carry out all of the maintenance at the center. When we need furniture, or a bricklayer, the school provides. The IML has never given me any money. But we arrange other solutions to manage things. The Hospital das Clínicas has lent me a very expensive machine, which is the x-ray developer. It was no longer useful for the HC to take radiographs on live patients, but it serves for taking them of bones, giving excellent quality. Therefore, so how am I going to purchase a top quality piece of equipment? I get a loan of that piece of equipment that belongs to the HC. The maintenance material for the equipment is donated by the IML, who cannot give me the money but can donate the liquid, the x-ray plates, etc. Summing up everything, I have help from the Hospital da Clínicas, employees loaned from the Municipal Secretary, from the State Secretary, material from the IML, and with this we mount and maintain the center.

Where does FAPESP come in?

The excellent toxicology laboratory, under the responsibility of Bruno Martinis, was mounted thanks to the Young Investigator Program. We didn’t get a cent from the university. In the laboratory, there’s almost R$ 1 million worth of equipment financed totally by FAPESP, if we summed up all that Bruno gained with the project, as well as the Young Investigator grant. Bruno and Marco Aurélio Guimarães also wrote their master’s and doctorate dissertations with grants from the Foundation.

Therefore, without this management it would be much more difficult for the Cemel to function?

One always has to look for original solutions. It may seem curious, but I don’t consider myself to be a researcher. I think I’m a strategist, let’s say that. Of course, I publish papers abroad, guide students in their master’s and doctorate degrees, and suggest a good part of the research that is being done here. But, above all I’m an educator. I breathed the same air as my mother – and until her death , she was one of the best educators that I had known.