Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah / National Cancer Institute / Science Photo Library

Lung cancer cells (purple) sensitive to targeted therapy drugsHuntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah / National Cancer Institute / Science Photo LibraryIn 1847, British doctor Henry Bence Jones found a protein characteristic of multiple myeloma in the urine of people suffering from this form of cancer, which attacks the bone marrow. Since then, about two dozen proteins measurable in the blood have been used as biomarkers of the appearance, growth, or regression of tumors. Some of these are quite well known today, like prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a marker for prostate tumors. They serve as useful tools, although they are not as precise as needed. In some cases, their levels may even be high when there is no tumor; in others, cancer may be present, but the protein is not detectable. In recent years, doctors and researchers at cancer centers in the United States, Europe, and Brazil have begun investigating ways to prevent the growth of certain types of cancer and exploring their response to certain treatments by detecting DNA fragments, cells, and even vesicles that the tumor releases into the blood.

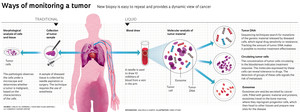

This strategy is known as liquid biopsy, so named because it only requires the collection of blood or other body fluids, like saliva or urine. Although the technique is still under development, it has been available at some hospitals in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro since mid-2016. It is awakening the interest of doctors and patients and sparking enthusiasm on the part of biotechnology companies, who have their eye on the market for equipment, disposables, and testing services, which sold $580 million in the United States in 2016 and is expected to reach $1.7 billion in 2021, as forecast by the research firm MarketsandMarkets. This is because liquid biopsy promises to offer advantages over traditional biopsies, which sample abnormal tissue through needle aspiration or surgery.

Imaging tests help to identify probable cancer, but it is the pathologist’s analysis of biopsied material that makes it possible to ascertain whether a tumor is malignant and determine its characteristics—information that is vital in defining treatment. While tissue biopsy is more informative, it is an invasive procedure that may require hospitalization and anesthesia. In certain cases, a decision is made against tissue biopsy because the tumor lies dangerously close to a major artery or vital organ. Another complicating factor is that tumors are formed out of different cell populations, which change over time. Given this heterogeneity and variability, the tumor information furnished by a traditional biopsy might not be the most complete or the most up-to-date. These challenges have driven the search for alternatives to tissue biopsy that are more reliable and easier to perform, like liquid biopsy. Since this new test can be repeated more often, doctors and researchers have started to see the technique as a possible option when accompanying the growth of certain types of cancer, monitoring treatment response, and trying to identify the recurrence of a tumor before it can be detected through imaging.

The version of liquid biopsy that detects genetic material from the tumor as it circulates in the bloodstream, known as tumor DNA, has already been adopted at some cancer centers in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, as well as outside Brazil. In support of its use, there is evidence that circulating tumor DNA provides a better reflection of the activity of neoplastic cells and the changes that cancer undergoes over time and during treatment than do traditional biopsy or protein markers.

In the late 1990s, researchers in France and the United States observed that the blood of individuals with cancer contained more DNA. Soon after, while working on her master’s degree under the advisorship of British biochemist Andrew Simpson, at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (ILPC) in São Paulo, Brazilian biologist Diana Nunes proved that this material actually came from tumors. In partnership with oncologist Luiz Paulo Kowalski of the A.C.Camargo Cancer Center, Nunes analyzed genetic material extracted from the saliva and blood of individuals suffering from cancer of the mouth. In an article published in the International Journal of Cancer in 2001, the three scientists proved that part of the DNA found in these fluids presented the same defect as the tumor cells and therefore could only have come from the tumor. “This was the beginning of liquid biopsy,” recalls biologist Emmanuel Dias-Neto, coordinator of the Medical Genomics Group at A.C.Camargo, where Nunes now works.

Over the past 10 years, strides in genetic sequencing techniques have made it easier to identify the changes characteristic of different tumor types and track them in the blood. The first commercial liquid biopsy test was developed by a multinational pharmaceutical firm, Roche, and released for use in the United States in early 2015. In June 2016, a molecular testing laboratory in Rio de Janeiro, Progenética, began performing liquid biopsies using the imported kit.

The test detects DNA fragments in the blood that display an alteration in the EGFR gene specific to adenocarcinoma of the lung, the most common type of lung cancer, especially among non-smokers. Known as T790M, this mutation indicates that a tumor has developed resistance to first- and second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), drugs that target tumor cells while sparing healthy ones.

Since August 2016, the A.C.Camargo Cancer Center in São Paulo has been offering a broader version of the test, which it designed. Developed by the team of biochemist Dirce Carraro, the test detects three other EGFR gene mutations, in addition to T790M, that make the adenocarcinoma sensitive to TKIs. Even before the test was available to doctors at the hospital, oncologist Helano Freitas used it to guide the treatment of some individuals under his care who had adenocarcinoma. The TKIs were no longer having any effect for 15 of his patients and their tumors had begun to grow again. Freitas wanted to know which of them had the resistance mutation and might benefit from a third-generation inhibitor. At the time, he was taking part in an international clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of this new generation of the drug, which is already on the market in the United States, and he was able to enroll new participants. Seven of his 15 patients had the mutation and started receiving third-generation TKIs.

Since August 2016, the A.C.Camargo Cancer Center in São Paulo has been offering a broader version of the test, which it designed. Developed by the team of biochemist Dirce Carraro, the test detects three other EGFR gene mutations, in addition to T790M, that make the adenocarcinoma sensitive to TKIs. Even before the test was available to doctors at the hospital, oncologist Helano Freitas used it to guide the treatment of some individuals under his care who had adenocarcinoma. The TKIs were no longer having any effect for 15 of his patients and their tumors had begun to grow again. Freitas wanted to know which of them had the resistance mutation and might benefit from a third-generation inhibitor. At the time, he was taking part in an international clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of this new generation of the drug, which is already on the market in the United States, and he was able to enroll new participants. Seven of his 15 patients had the mutation and started receiving third-generation TKIs.

In December 2016, when the enrollment period ended for new participants, Freitas stopped ordering liquid biopsies for these cases. Although Brazil approved the third-generation drug for use in January 2017, it cannot yet be marketed in the country, because its price has not been defined. It is expected to cost more than first- and second-generation TKIs, whose price tag ranges from R$5,000 to R$8,000 per month. “What good does it do someone to have the test and know he can benefit from the drug, if he can’t have access to it?” the doctor asks.

In addition to alterations in the EGFR gene, the liquid biopsy made available at A.C.Camargo by Dirce Carraro’s team assesses mutations in 13 other genes. Some are often altered in lung cancer, others in intestinal tumors (colorectal cancer), and still others in melanoma, the most aggressive form of skin cancer. In these cases, as in pulmonary adenocarcinoma, liquid biopsy helps guide treatment by enabling the detection of mutations associated with drug sensitivity or resistance.

“Interested doctors can also order this test for other tumors that present some of these altered genes,” suggests Carraro, coordinator of A.C.Camargo’s Genomics and Molecular Biology Group. Carraro has been working for three years to develop a liquid biopsy that will help monitor how people with Wilms’ tumor respond to chemotherapy. This rare form of kidney cancer is usually detected between the ages of 2 and 5 and strikes one in every 10,000 children. The long-term goal is to use the test for diagnostic purposes as well. “If we can eventually achieve early diagnosis by detecting tumor DNA in the urine, it might be feasible to start treatment before symptoms appear,” Carraro suggests.

At Sírio-Libanês Hospital (HSL), the team of researcher Anamaria Camargo is experimenting with the use of liquid biopsies to monitor drug sensitivity in three types of tumors—lung, breast, and colorectal—and detect the development of resistance to treatment early on. The researchers are currently doing monthly bloodwork to monitor 30 people in each of these three groups. “We are quantifying DNA molecules that carry the mutations associated with resistance to treatment in each of these types of cancer and verifying whether there is an association between the amount of altered DNA, treatment response, and the clinical progression of the disease,” says Camargo, coordinator of the Molecular Oncology Center at HSL.

Camargo began working with liquid biopsies nearly 10 years ago. In partnership with Angelita Habr-Gama and Rodrigo Oliva Perez, digestive tract surgeons at the Angelita e Joaquim Gama Institute, she began developing a personalized test both to verify whether adjuvant therapy of rectal tumors, using radiation treatment and chemotherapy, was having the desired effect and also to detect recurrence. The test proved viable, but a pilot experiment showed that some tweaking is necessary. While the test managed to detect recurrence of the tumor about 18 months earlier than other methods, it did not always determine whether treatment had completely wiped out the disease (see Pesquisa FAPESP Issue nº 237).

The blood of someone with cancer carries more than tumor DNA. In certain situations, it can hold cells that have detached from the original cancer, as well as small sacs, or vesicles, called exosomes, which are filled with the content of tumor cells.

Photo Ludmilla Chinen / A.C.Camargo Cancer Center

Formed out of tumor cells that travel in a group, microemboli signal the risk of metastasisPhoto Ludmilla Chinen / A.C.Camargo Cancer CenterBiochemist Ludmilla Chinen, researcher at A.C.Camargo, found that circulating tumor cells also reveal a great deal about the disease. She and her collaborators have followed 280 people with different kinds of cancer and noted that the concentration of tumor cells in the blood can serve as a dynamic indicator of the response to drugs. “We can tell if the treatment is working in two months, almost half as long as it would take to discover with imaging,” says Chinen.

In recent years, Chinen and her collaborators have also found that molecules expressed by circulating tumor cells can indicate tolerance to certain medications used to fight colorectal cancer. The researchers further suspect that analysis of these cells may predict the appearance of metastasis. They followed people with advanced non-metastatic head and neck cancer and saw that when tumor cells travel in small groups, called microemboli, the odds are greater for the emergence of new sites of the disease.

Around 2008, the team of physician David Lyden, at Cornell University, began observing that exosomes could act as cell messengers, delivering to other tissues information that is needed to prepare new tumor sites. With the collaboration of Brazilian biochemists Bruno Costa Silva and Vilma Regina Martins, the Cornell team devised a model of melanoma metastasis in mice. The researchers injected exosomes characteristic of melanoma into the bloodstreams of mice with skin cancer and followed the path of the vesicles.

In a paper published in Nature Medicine in 2012, the scientists explained that exosomes, which are found in greater quantity in more aggressive types of melanoma, first traveled to the bone marrow. There, the information contained in the exosomes reprogrammed progenitor cells and directed them to the lungs, where they produced new blood vessels and triggered inflammation. This inflammation in turn fostered a premetastatic environment and chemically attracted the tumor cells circulating in the blood. “The tumor releases these vesicles before the cells start detaching from it and traveling,” explains Martins, research director at A.C.Camargo. “This makes exosomes a potential target of treatments that try to block the formation of metastasis,” the biochemist says.

Some specialists estimate that 20% to 25% of the 30,000 new cases of lung cancer that appear in Brazil every year have some EGFR gene mutation and may benefit from targeted therapies. “From a public health standpoint, it’s worth discussing the possibility of making liquid biopsy and these drugs available through the Unified Health System (SUS),” says Helano Freitas.

Despite these numbers, it is expected to be some time before it becomes routine at more hospitals and cancer centers to use liquid biopsy to detect circulating tumor cells and exosomes. In the beginning, even the most solid version of the test, which identifies tumor DNA, will likely remain restricted to those with private health insurance or who pay out of pocket.

“Brazil did not prepare itself to provide molecular diagnosis through its Unified Health System,” critiques oncologist Carlos Gil Ferreira, who was director of clinical research at the National Cancer Institute (INCA) in Rio de Janeiro from 2002 to 2015. In late 2016, he left his partnership at the Progenética laboratory and now coordinates oncology research at the D’Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR), where a team is working to develop a form of liquid biopsy for liver tumors. “Because of cost issues and a question of strategy, Brazil isn’t ready for the era of precision medicine.”

Roger Chammas, professor of oncology at the University of São Paulo School of Medicine (FMUSP) and coordinator of the Center for Translational Research in Oncology at the São Paulo State Cancer Institute (ICESP), believes that the SUS will only begin offering liquid biopsy once there is greater access to targeted therapies, which could be guided by these exams.

Portuguese biologist Rui Reis is more optimistic. Reis coordinates the Research Center in Molecular Oncology at Barretos Cancer Hospital, in rural São Paulo, which serves only SUS patients, and he feels that careful calculations would show that the advantages afforded by this type of test could actually lower the cost of cancer treatment. “These tests are expensive at the outset, but costs drop when they begin to be used on a broad scale,” he says. Before contemplating more widespread use of liquid biopsy, it has to be determined which of the techniques work best. “Everyone is looking for the best method,” says Reis.

Projects

1. Epidemiology and genomics of gastric adenocarcinomas in Brazil (nº 14/26897-0); Grant Mechanism Thematic project; Principal Investigator Emmanuel Dias-Neto (A.C.Camargo Cancer Center); Investment R$2,632,274.23.

2. Exploring the exome of salivary mucoepidermoid carcinoma in search of more accurate prognostic markers (nº 14/07249-7); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Luiz Paulo Kowalski (A.C.Camargo Cancer Center); Investment R$256,192.74.

3. Detection of circulating tumor cells and their correlation with clinical evolution in epidermoid carcinoma of head and neck (nº 13/08125-7); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Ludmilla Thomé Domingos Chinen (A.C.Camargo Cancer Center); Investment R$306,452.01.

4. Molecular aspects involved in the development and progression of breast ductal carcinoma: investigation of carcinoma in situ progression and the role of BRCA1 mutation in the triple negative tumor (nº 13/23277-8); Grant Mechanism Thematic project; Principal Investigator Dirce Maria Carraro (A.C.Camargo Cancer Center); Investment R$2,364,609.18.

Scientific articles

NUNES, D. N.; KOWALSKI, L. P. and SIMPSON, A. J. Circulating tumor-derived DNA may permit the early diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. International Journal of Cancer. February 13, 2001.

TORREZAN, G. T. et al. Recurrent somatic mutation in DROSHA induces microRNA profile changes in Wilms’ tumour. Nature Communications. June 9, 2014.

ABDALLA, E. A. et al. Thymidylate synthase expression in circulating tumor cells: A new tool to predict 5-fluorouracil resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. International Journal of Cancer. Vol. 137, No. 6, pp. 1397-405. 2015.

ABDALLA, E. A. et al. MRP1 expression in CTCs confers resistance to irinotecan-based chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. International Journal of Cancer. Vol. 139, No. 4, pp. 890-8. 2016.

BUIM, M. E. et al. Detection of KRAS mutations in circulating tumor cells from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Biology and Therapy. Vol. 16, No. 9, pp. 1289-95. 2015.

AMORIM, M. et al. The overexpression of a single oncogene (ERBB2/HER2) alters the proteomic landscape of extracellular vesicles. Proteomics. Vol. 14, No. 12, pp. 1472-79. 2014.

PEINADO, H. et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nature Medicine. Vol. 18, No. 6, pp. 883-91. 2012.