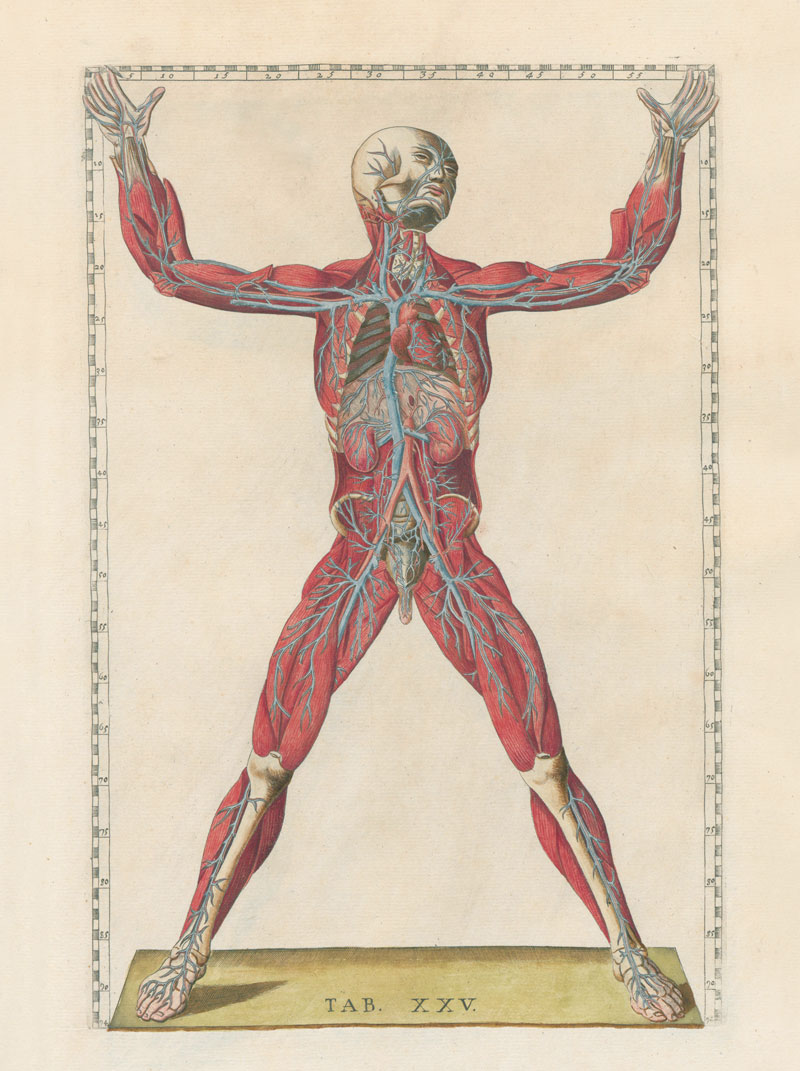

Tabulae Anatomicae / Bartolomeo EustachioA plate from the book Tabulae Anatomicae, published in 1552 by Italian anatomist Bartolomeo Eustachio (c. 1500–1574), depicts the heart and the great vessels of the human bodyTabulae Anatomicae / Bartolomeo Eustachio

“We are flipping the script.” With this bold and confident statement, physician and pharmacologist Gilberto De Nucci concluded lunch at an Italian restaurant in São Paulo last October. The conversation had been rich with new insights into the biochemistry and physiology of the heart and blood vessels—ideas that required time to fully digest. For more than an hour, De Nucci had outlined the findings of his research group at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), which aims to transform the understanding of how the body regulates heartbeat, blood pressure, penile erection, and ejaculation.

Detailed in over 30 scientific articles published since 2020, the most recent appearing in Life Sciences in February, his team’s findings suggest that the inner lining of blood vessels and heart chambers is the primary production site for a family of compounds that control everything from vascular contraction to the rhythm and strength of the heartbeat. Until now, cardiologists and physiologists believed that the synthesis and release of these compounds, known as catecholamines, occurred exclusively within specific nerve cells.

Three of the best-known catecholamines are dopamine, noradrenaline, and adrenaline. Identified between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, these are produced in different regions of the brain and central nervous system, where they act as neurotransmitters, transmitting commands from one cell to another. In both real threats, such as an armed robbery, and perceived ones, like the fear of being mugged, they are synthesized and released by fibers of the sympathetic nervous system, which extend from the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord to various organs and tissues. In such moments, catecholamines, especially noradrenaline, prime the body for fight or flight: they accelerate the heartbeat, trigger the liver to release glucose, constrict blood vessels, and raise blood pressure, mobilizing blood and energy to the muscles.

It was partly by chance that the UNICAMP group began uncovering findings that now challenge this foundational principle of cardiovascular physiology. In mid-2010, during a conversation with a zoologist in Rio de Janeiro, De Nucci was surprised to learn that reptiles were the first animals to evolve penises and that copulation in the South American rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus terrificus) could last up to 28 hours. Years earlier, De Nucci had developed Lodenafil, a compound for the pharmaceutical company Cristália, based in the interior of São Paulo, to treat erectile dysfunction. Marketed under the name Helleva, it functions similarly to Sildenafil (Viagra). Intrigued by the biology of these snakes, De Nucci set out to investigate the mechanisms behind such prolonged erections.

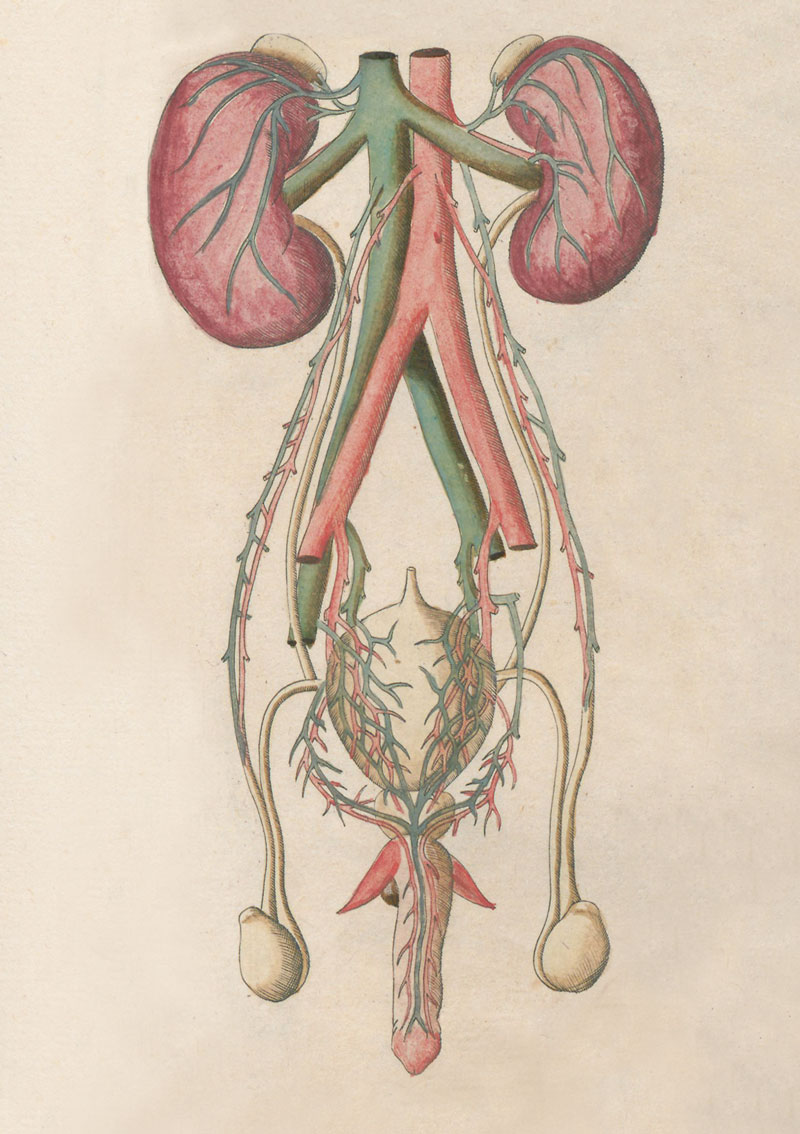

In humans, erections are affected by emotional factors, neural function, and vascular mechanisms. In response to sexual stimulation, nerves transmitting signals from the brain to the penis stimulate blood vessels to produce nitric oxide (NO). Synthesized by endothelial cells—the inner lining of veins and arteries—NO triggers chemical reactions that cause the vascular smooth muscles to relax. As a result, the penis fills with blood and becomes erect. After a certain period, fibers of the sympathetic nervous system release catecholamines—primarily noradrenaline—which induce contraction of the genital tract muscles, leading to ejaculation. Simultaneously, these catecholamines cause the blood vessels in the penis to constrict, resulting in flaccidity.

In an initial study published in 2011 in The Journal of Sexual Medicine, De Nucci found that the mechanism responsible for erection in the rattlesnake was similar to that in humans and other mammals—dependent on nitric oxide.

The difference emerged in experiments analyzing vascular muscle contraction. In mammals, the loss of erection is triggered by the release of catecholamines from sympathetic nervous system fibers, which cause the muscles to contract and expel blood from the penis. This was not the case in the rattlesnake.

In the snake, the stimulus for vascular muscle contraction—and the resulting penile flaccidity—did not originate from the sympathetic nervous system. Researchers discovered this when they treated the tissue with tetrodotoxin, a compound extracted from the puffer fish. In mammals, tetrodotoxin blocks nerve activity, preventing the release of catecholamines and thereby maintaining erection. However, in the rattlesnake, the vessels still contracted and caused erection loss even when nerve signals were blocked, as the group demonstrated in a 2017 article in PLOS ONE. This indicated that the signal for vascular contraction originated from a different source.

Tabulae Anatomicae / Bartolomeo EustachioModulated by catecholamines, the contraction of ducts in the genital tract is responsible for triggering ejaculationTabulae Anatomicae / Bartolomeo Eustachio

Using antibodies, the researchers located, in the endothelium of the rattlesnake’s corpus cavernosum—the cylindrical erectile tissue inside the penis—the enzyme responsible for producing a precursor of dopamine, a catecholamine that also induces muscle contraction. “The ability to contract disappeared when we repeated the experiments after removing the endothelium from the corpus cavernosum,” said De Nucci, who is also a professor at the University of São Paulo (USP), during the 2024 luncheon.

The same effect was observed in tests on the corpus cavernosum and the aorta of the corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus), the Bothrops snake (Bothrops sp.), and the red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonaria). The vascular muscles lost their ability to contract when the endothelium was removed and dopamine was eliminated.

At the time, the researchers believed that dopamine synthesis by the endothelium was a unique feature of reptiles. They had searched for the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which produces a dopamine precursor, in the corpus cavernosum of marmosets but did not find it; it was present only in the sympathetic nerves. However, years earlier, researchers in Italy had reported the production of catecholamines by bovine aortic endothelial cells cultured under specific conditions.

This understanding began to shift when pharmacologist José Britto Júnior joined the team. During his PhD interview in 2018, he proposed, “Why not study the vessels of the human umbilical cord? It’s a tissue without innervation and easy to obtain, as it is discarded after childbirth.”

In the initial tests, the researchers found dopamine present in the endothelium of the artery and vein of the umbilical cord. When this endothelial layer was removed, dopamine was no longer detectable. They also observed that this catecholamine’s ability to induce vascular muscle contraction increased when nitric oxide synthesis was blocked, even with the endothelium intact.

The results, published in Pharmacology Research & Perspectives in 2020, marked a new turning point. During a group meeting, pharmacologist Edson Antunes from UNICAMP raised an important question: “If the endothelium produces both NO and dopamine, don’t they combine?”

At the time, the answer was unknown, though the possibility existed. More than two decades earlier, a group at the University of Naples Federico II in Italy had combined catecholamines and NO in the laboratory and obtained a derivative compound, initially believed to be toxic. Concurrently, researchers at Keio University in Japan had identified a form of noradrenaline in rat brains that incorporated NO, known as 6-nitronoradrenaline.

De Nucci began searching for chemical companies capable of synthesizing similar compounds and found one in Canada. He imported samples of 6-nitrodopamine (6-ND)—a combination of dopamine and NO—which Britto and other team members used to calibrate the mass spectrometer, a device that separates and quantifies molecules based on atomic mass, and to test the compounds extracted from the endothelium of umbilical vessels.

Bingo! The presence of 6-nitrodopamine was confirmed, as the group reported in a 2021 article in Life Sciences. Moreover, the concentration of 6-ND decreased when NO synthesis was inhibited, indicating that NO was involved in its production. The team later determined that this was the principal biochemical pathway, responsible for 60% to 70% of the 6-ND released by the endothelium, although a secondary pathway also exists.

Tabulae Anatomicae / Bartolomeo EustachioAs illustrated in another Tabulae Anatomicae plate, the interior of the heart chambers produces compounds that regulate both the rhythm and the force of blood pumpingTabulae Anatomicae / Bartolomeo Eustachio

“The idea that catecholamines are also released by the vessels is attractive because the endothelium is in contact with the blood and well positioned to sense metabolic signals and changes in circulatory tension,” said biologist and physiologist Tobias Wang of Aarhus University in Denmark, a recent collaborator with the UNICAMP team, in an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP. “As this proposal is provocative, it is still viewed with skepticism.”

In vessel contraction and relaxation tests, Britto Júnior observed that the effect of 6-ND contrasted sharply with that of dopamine: while dopamine promoted contraction, 6-ND inhibited it. It appears that both compounds compete for binding to the same receptor—D2—which mediates dopamine’s contractile action. When 6-ND binds to this receptor, it blocks the effect.

“It’s also possible that 6-nitrodopamine binds to the same receptor as dopamine, but at a different site, which could explain the potentiation of dopamine’s effects in certain situations,” suggests biomedical scientist and pharmacologist Regina Markus, from USP, who was not involved in the studies.

Following this discovery, the Campinas group began measuring 6-ND levels and characterizing its effects in other vessels and organs of reptiles and mammals. Tests on veins and arteries confirmed 6-ND’s ability to attenuate dopamine-induced contraction. Experiments on anesthetized rats also demonstrated that 6-ND is produced within the heart chambers (atria and ventricles) in greater quantities than classic catecholamines. Furthermore, 6-ND was shown to be between 100 and 10,000 times more potent than them.

In the atrium, which regulates the heart’s rhythm, 6-ND increases the frequency of contraction. In the ventricle, it enhances the force of blood pumping. Its effect is also significantly longer-lasting: up to one hour, compared to the few minutes typical of drugs currently used in emergencies for cardiac arrest. “6-nitrodopamine,” says Britto Júnior, “also potentiates the effect of other catecholamines, which could, in principle, allow their use at lower doses than those currently required.”

According to De Nucci, the results demonstrate the capacity of blood vessels and the heart to self-regulate. If confirmed, this mechanism could help explain why patients who undergo heart and lung transplants—procedures that eliminate the innervation of these organs—are still able to maintain heart rate and blood pressure levels comparable to those of healthy individuals.

“My impression is that the vascular effects of 6-nitrodopamine may influence the self-regulation of blood flow at local and regional levels, acting on capillaries and other vessels without innervation,” says cardiovascular physiologist Ruy Campos Júnior, from the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), who is investigating the role of hypertension in kidney disease and was not involved in the studies. “The challenge is to move beyond laboratory experiments and understand its function in regulating the heart under physiological conditions,” he states.

“The findings do suggest that these nitrocatecholamines exist in the vascular wall and may have a functional role, but they still don’t tell us how significant that role is in controlling vessel relaxation in vivo,” adds cardiologist Francisco Laurindo, from USP’s Heart Institute (InCor), an expert in vascular system function.

6-nitrodopamine also appears to play an important role in the genitourinary system. It is produced in the vas deferens, which transports sperm from the testicles to the urethra, and in the seminal vesicle, which produces semen. In these structures, 6-ND induces the contractions necessary for ejaculation. In the corpus cavernosum, it acts as a potent vasodilator. “We are revealing a new mechanism through which nitric oxide causes vasodilation. In addition to directly relaxing the vessels, nitric oxide, via 6-nitrodopamine, inhibits the vasoconstrictive effect of dopamine,” says Britto Júnior, now a researcher at King’s College London in the UK.

Britto and the Campinas team are currently investigating the effects of another catecholamine they discovered in mammals: 6-cyanocatecholamine, which contains cyanide—a highly toxic compound.

The story above was published with the title “Challenging beliefs” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Projects

1. Pharmacological, electrophysiological, and morphological identification and characterization of a new TTX-resistant sodium channel coupled to the smooth muscle of the corpus cavernosum in snakes (nº 11/11828-4); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Gilberto De Nucci (UNICAMP); Investment R$2,247,830.77.

2.Modulation of soluble guanylate cyclase and intracellular cyclic nucleotide levels in lower urinary tract organs and the prostate (nº 17/15175-1); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Edson Antunes (UNICAMP); Investment R$4,687,065.45.

3.Assessment of the pathophysiological role of endothelial catecholamines (nº 19/16805-4); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Gilberto De Nucci (UNICAMP); Investment R$7,786,325.74.

4. Assessment of the actions of 6-Nitrodopamine on renal and genitourinary function (nº 23/01376-6); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Roberto Zatz (USP); Investment R$187,275.98.

Scientific articles

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. 6-cyanodopamine as an endogenous modulator of heart chronotropism and inotropism. Life Sciences. Feb. 19, 2025.

CAPEL, R. O. et al. Role of a novel tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel in the nitrergic relaxation of corpus cavernosum from the South American rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. June 1, 2011.

CAMPOS, R. et al. Tetrodotoxin-insensitive electrical field stimulation-induced contractions on Crotalus durissus terrificus corpus cavernosum. PLOS ONE. Aug. 24, 2017.

CAMPOS, R. et al. Electrical field stimulation-induced contractions on Pantherophis guttatus corpora cavernosa and aortae. PLOS ONE. Apr. 19, 2018.

SORRIENTO, D. et al. Endothelial cells are able to synthesize and release catecholamines both in vitro and in vivo. Hypertension. 2012.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. Endothelium-derived dopamine modulates EFS-induced contractions of human umbilical vessels. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. June 22, 2020.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. 6-nitrodopamine is released by human umbilical cord vessels and modulates vascular reactivity. Life Sciences. July 1, 2021.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. GKT137831 and hydrogen peroxide increase the release of 6-nitrodopamine from the human umbilical artery, rat-isolated right atrium, and rat-isolated vas deferens. Frontiers in Pharmacology. Apr. 5, 2024.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. 6-nitrodopamine is an endogenous modulator of rat heart chronotropism. Life Sciences. Oct. 15, 2022.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. 6-nitrodopamine is a major endogenous modulator of human vas deferens contractility. Andrology. Aug. 7, 2022.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. 6-nitrodopamine is the potent endogenous positive inotropic agent in the isolated rat heart. Life. Oct. 4, 2023.

LIMA, A. T. et al. 6-nitrodopamine is an endogenous mediator of the rabbit corpus cavernosum relaxation. Andrology. Dec. 19, 2023.

BRITTO-JUNIOR, J. et al. Epithelium-derived 6-nitrodopamine modulates noradrenaline-induced contractions in human seminal vesicles. Life Sciences. July 1, 2024.

JÚNIOR, G. Q. et al. Measurement of 6-cyanodopamine, 6-nitrodopa, 6-nitrodopamine and 6-nitroadrenaline by LC-MS/MS in Krebs-Henseleit solution. Assessment of basal release from rabbit isolated right atrium and ventricles. Biomedical Chromatography. July 10, 2023.

DAL POZZO, C. F. S. et al. Basal release of 6cyanodopamine from rat isolated vas deferens and its role on the tissue contractility. European Journal of Physiology. July 4, 2024.