Nine institutions—including universities, research institutes, a branch of the Brazilian Navy, and four companies—are joining forces to develop the resources and technology needed to manufacture nuclear microreactors in Brazil. If successful, the project will place the country among the pioneers of this electricity generation system. Microreactors are smaller than conventional nuclear reactors that generate energy via fission of the atomic nucleus. The objective is to develop machines capable of generating between one and five megawatts (MW) of energy. One megawatt is enough to supply about 1,000 people. Just over one-fifth of Brazilian municipalities are home to 5,000 inhabitants or fewer, meaning they could be served by just one microreactor.

The remotely controlled machine, the size of a 40-foot shipping container at 12 meters (m) long, 2.4 m wide, and 2.6 m high, could replace the diesel electricity generators currently used by isolated communities, industry, hospitals, data centers, and other establishments that need an alternative or additional system to the conventional electricity grid.

“Nuclear microreactors can generate energy uninterrupted for up to a decade without needing to be refueled,” says the project’s technical lead, physicist João Manoel Losada Moreira of the graduate program in energy at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC) and the startup Terminus Energia. “One of its major advantages is that it does not emit greenhouse gases [GHGs].”

The Brazilian microreactor development project, set to be located alongside the Argonauta reactor at the Institute of Nuclear Engineering (IEN) in Rio de Janeiro, will need to overcome several technological challenges in its aim to create a legacy for Brazilian nuclear research. Some of the required materials that will demand a local effort include the design and production of heat pipes capable of withstanding temperatures of 800 degrees Celsius (ºC), and the development of a graphite and beryllium production chain. “Heat pipes for nuclear use and beryllium are two key materials for which international trade is restricted,” explains the UFABC researcher.

The initiative is still in the intermediate phase of development. Its technology readiness level (TRL) is currently three, the stage in which the viability of the proposed solution is demonstrated through analytical or experimental studies in a lab. Created by NASA, the TRL scale indicates the maturity of technological innovations in various economic sectors. The final level is 9, when the solution is in continuous production. The goal of Brazilian researchers is to reach TRL 6, demonstrating the critical functions of the new technology in specific experiments, within three years.

In addition to UFABC, the project also involves partners from the federal universities of Ceará (UFC), Minas Gerais (UFMG), and Santa Catarina (UFSC); the Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN) and IEN, both of which are affiliated with the National Commission for Nuclear Energy (CNEN); the National Institute for Telecommunications (INATEL); the Brazilian Navy, through its Nuclear and Technological Development Division; public companies Amazônia Azul Tecnologias de Defesa (Amazul) and Indústrias Nucleares Brasileiras (INB); Rio de Janeiro–based startup Terminus Energia; and Santa Catarina–based company Diamante Geração de Energia. The initiative has a budget of R$50 million, of which R$30 million was allocated this year by the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP), and R$20 million is from Diamante Geração de Energia.

The microreactor technology is inspired by nuclear reactors designed to generate power for space missions. It will not use water or gas in its cooling and heat conduction system, as is the case in traditional nuclear power plants. Heat will be recovered using heat pipe technology, the same as is used for reactors in space (see infographic).

The device will consist of a small reactor that will perform nuclear fission, in which the nuclei of uranium atoms are split by a neutron chain reaction. The result of fission is the release of energy in the form of heat. The uranium atoms will be contained in fuel rods placed inside the reactor. The neutrons generated by the fission process will initially have a high kinetic energy (speed)—in the region of 2 million electron volts (eV)—but the fission chain reaction is more efficient when the neutrons are moving slowly, at around 1 eV. Graphite or beryllium, known as energy moderators, can be used to lower the energy of the neutrons.

“In a traditional reactor, neutrons are slowed down by heated water,” explains materials engineer Jesualdo Luiz Rossi, a researcher at IPEN responsible for developing the microreactor’s moderator system. “Two other elements can be used for the same task: graphite or beryllium oxide [BeO].” Graphite is a solid carbon compound available on the global market. To use it as a decelerating agent, the reactor core will need to be around one meter in diameter, says Moreira. If beryllium is used, it can be just 60 centimeters.

A set of heat pipes will conduct the heat generated—around 800 ºC—from the reactor to a heat exchanger in the power conversion system, which will transform thermal energy into electricity. According to Moreira, two traditional power conversion systems are being analyzed by the team: the Stirling and Brayton thermodynamic cycles. the teams from UFC, UFMG, and UFSC are responsible for developing heat pipes capable of functioning at 800 ºC.

The core of the heat pipes will be pure sodium, an efficient heat conductor. According to the UFABC researcher, there is no data available on the production of heat pipes for nuclear applications, because they are treated as an industrial secret by those who own the technology.

The microreactor also includes a system that uses rotating neutron-absorbing rods and drums to control the fission chain reaction. This system, essential to the safety of the process, allows the power level of the microreactor to be stabilized, increased, reduced, or even zeroed by turning it off. “The neutron-absorbing material will be made of boron carbide, a strong, durable ceramic material,” explains Rossi. The technology for generating boron carbide already exists, but Brazil does not manufacture the material. The Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research will be responsible for developing the production process, which will later be transferred to any interested companies.

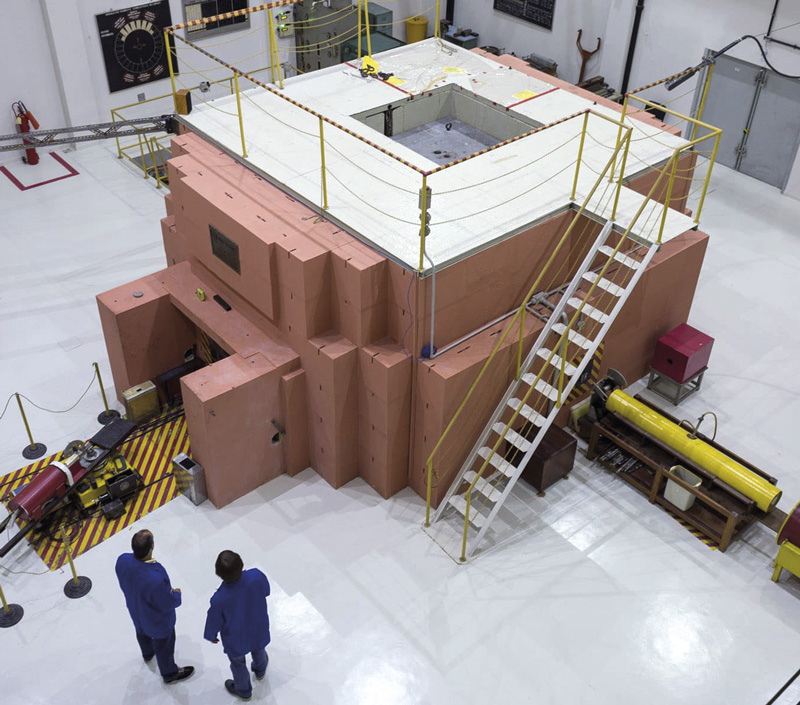

IEN CollectionThe Brazilian microreactor will be installed on the premises of the Argonauta nuclear research reactor in Rio de JaneiroIEN Collection

Steel containment and shielding

Another technological development that will be needed is a digital remote control system for the microreactors, a task being carried out by INATEL and IEN. “We are proposing an innovative system that in addition to remote control of the microreactor, will also allow the equipment to be integrated with microgrids, meaning self-sufficient local power grids that do not need to be connected to the national grid,” says Moreira.

In microgrids, energy is generated by small equipment, generally via wind, solar, or a combination of sources. A microgrid can use a nuclear microreactor alone or in conjunction with intermittent generators, which depend on the level of sunlight or wind, to stabilize the local energy supply.

The equipment is shielded by a containment system made of steel or layers of steel and lead, which surround the reactor system and serve to contain radiation during operation or radioactive material in the event of an accident. Moreira explains that the cooling process and heat conduction via heat pipes operate at near atmospheric pressure. “In large nuclear power plants, the biggest safety challenge is to maintain cooling when the reactor is suddenly shut down. It is the loss of cooling systems that causes pressure to rise beyond control, leading to the risk of radioactive material leaking,” he says. “With microreactors, because the power levels are about 1,000 times lower than in a large reactor, if it is suddenly shut down, it is much easier to keep it cool.”

In a 2024 paper in the journal Nuclear Engineering and Design, Moreira and colleagues from UFBAC and Terminus presented the foundations and details of the design that will guide the construction of the microreactor core. They also demonstrated a potential reactor power cycle of 8.7 years without refueling and compared the Brazilian initiative with three projects considered international references, whose fuel self-sufficiency is limited to five years.

Uranium enrichment for the microreactor could be as high as 20%, a figure that only reaches up to 5% in large commercial reactors. Initially, the Brazilian microreactor will use uranium dioxide (UO2) as fuel. Supplied by INB, it is the same fuel used at the nuclear power plants in Angra dos Reis, on the coast of Rio de Janeiro. At a later stage, when they are in commercial use, the plan is to recycle radioactive waste from the Angra dos Reis units for use as fuel in the microreactors—in Europe and Asia, recycling like this is already done on a small scale.

The potential for recycling nuclear fuel and the benefits in terms of reducing the radioactive decay time when the material is reused were outlined in an article published in Nuclear Engineering and Design in 2023 by researchers associated with the project.

Carina Johansen/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesPlatforms in the North Sea: Small reactors could be used to power offshore oil and gas platformsCarina Johansen/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Physicist Claudio Geraldo Schön, head of the nuclear engineering course at the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (Poli-USP), is not part of the research group working on the microreactor but believes that the devices are a safe technology. “If something occurs that is not within planned operations, there is no risk of it evolving into a nuclear accident. The risk that exists in large reactors is associated with the possibility of a radioactive core meltdown,” he explains. Microreactors, Schön explains, work at lower temperatures and there is no way for the core to reach melting point. “This occurs in traditional reactors due to the lack of liquid coolant, but a microreactor does not use fluids.” The fact that these devices are low-power and use less uranium also makes them safer, according to the scientist.

Incentivizing nuclear energy

Various companies and public and private research centers in other countries are working on nuclear microreactors, but to date, there are none in commercial operation. British company Rolls-Royce and US company Westinghouse are in advanced stages of development. The first machines, to be used exclusively by the US Army, are expected to enter operation later this year or in 2026.

The initial cost of the Brazilian microreactor is estimated at around US$10 million; when mass production begins, the cost is expected to fall. The electricity generation cost will be around R$990 per megawatt-hour (MWh), says Moreira. This value would make it slightly more economical than the diesel generators used by small communities in northern Brazil, which cost more than R$1,000 per MWh.

The Brazilian administration has shown an interest in producing more nuclear energy in the country. In May, during a visit to Russia, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva reiterated the government’s intention to establish a partnership with Russian state-owned nuclear energy company Rosatom, through which it will acquire technology related to small modular reactors (SMRs). These machines generate between 20 MW and 300 MW and can operate similarly to traditional reactors—for comparison, the Angra 1 plant has a capacity of 640 MW, while Angra 2 has a capacity of 1,350 MW. There are currently only three SMRs in operation worldwide: one in China and two in Russia.

In Brazil, through an agreement with the Alberto Luiz Coimbra Institute for Graduate Studies and Research in Engineering at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (COPPE-UFRJ), Petrobras is evaluating the use of SMRs on offshore oil platforms, to replace the currently used gas turbines. Switching from the current system to the new one should reduce GHG emissions.

Physicist Giovanni Laranjo Stefani, who is head of UFRJ’s department of nuclear engineering and researches nuclear reactors, believes that Brazil’s development of the technologies needed to build microreactors and SMRs could allow the country, considered neutral in global technological disputes, to establish itself as a supplier of equipment to the international market.

“It will also allow Brazil to rely on a clean, low-carbon, reliable energy source that is not dependent on weather fluctuations,” says Stefani, who is not part of the group responsible for the Brazilian microreactor project. “This aspect is really important for facilities where a continuous power supply is essential, such as hospitals and data centers.”

The story above was published with the title “Compact and powerful” in issue 353 of July/2025.

Scientific articles

ORLANDI, H. I. et al. Fuel element microreactor integrating a square UO2 fuel rod with an internal heat pipe. Nuclear Engineering and Design. Vol. 423, July 2024.

ESTANISLAU, F. B. G. L. et al. Assessment of alternative nuclear fuel cycles for the Brazilian nuclear energy system. Nuclear Engineering and Design. Vol. 415. Dec. 15, 2023.