Brazil’s supercomputer infrastructure is making significant advances, improving the high-performance computing (HPC) resources available for scientific research. The biggest steps forward are being taken by the National Laboratory for Scientific Computing (LNCC) in Petrópolis, a city located in the mountains outside Rio de Janeiro, the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) in Cachoeira Paulista, São Paulo State — both of which are linked to Brazil’s Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI) — and the Center for Computing in Engineering and Science at the University of Campinas (CCES-UNICAMP).

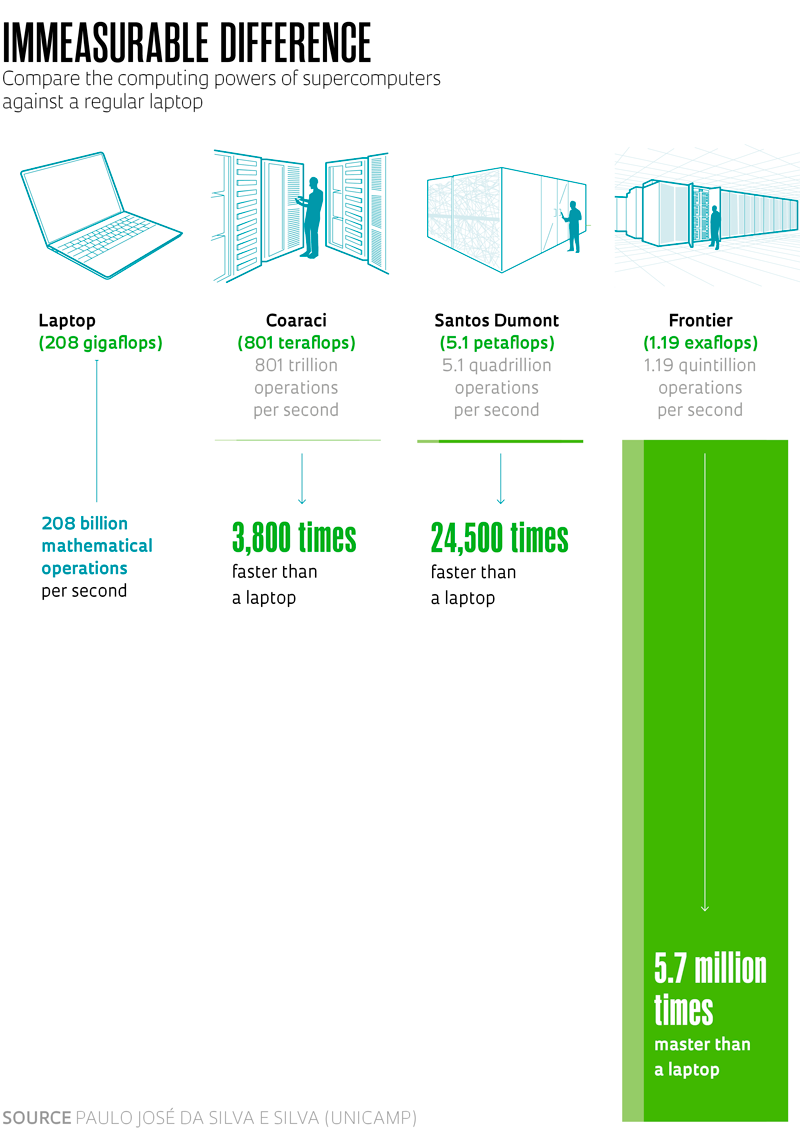

Supercomputers consist of thousands of small computers called nodes. Each node is equipped with its own memory and multiple processors. By working together, they are able to carry out extremely complex calculations at high speeds, in the quintillions (1018) of operations per second. These super machines are a powerful tool for scientific research, while also supporting various sectors of the economy, such as defense, energy, and health. More powerful computers allow scientists to solve complex problems in less time, experts explain.

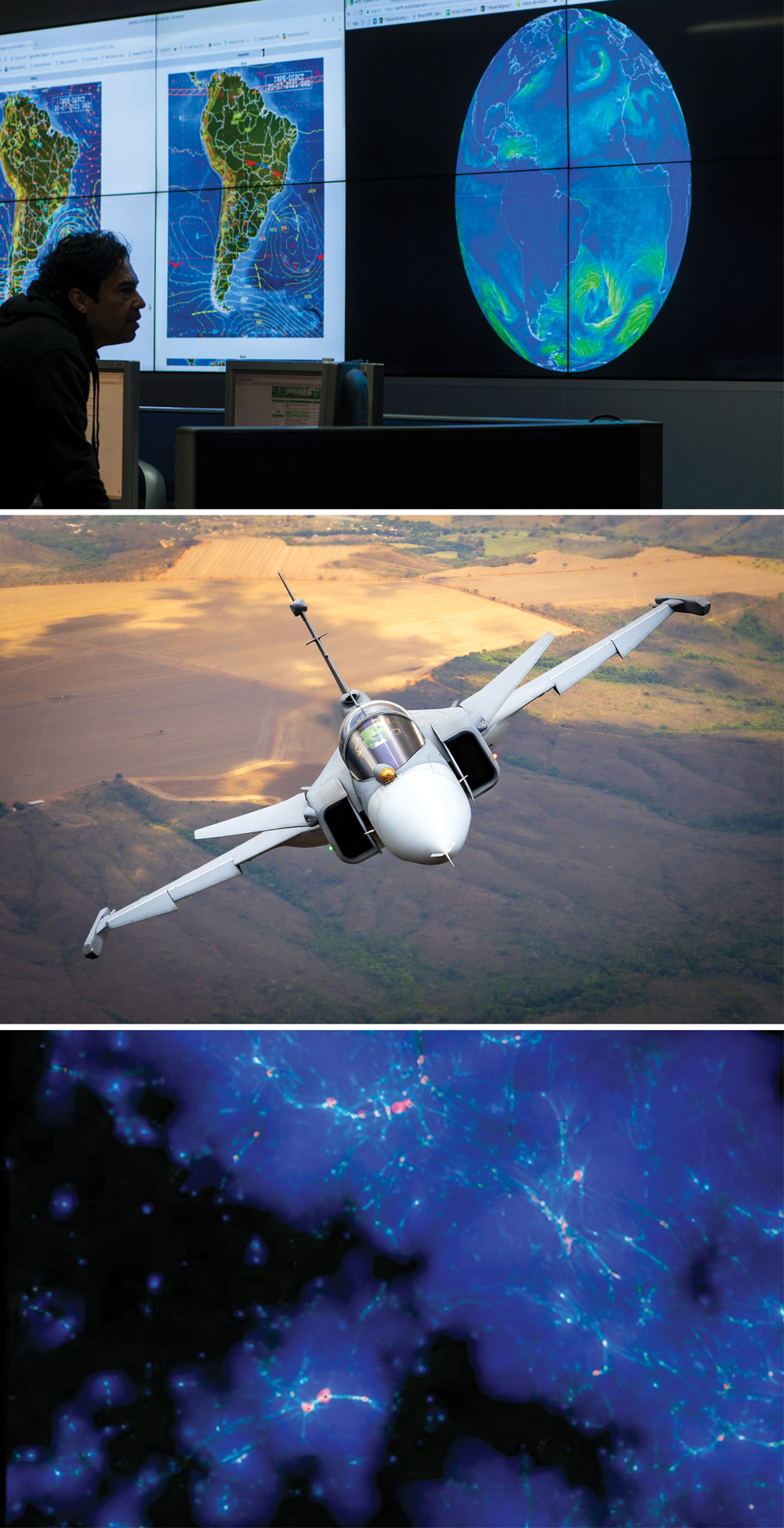

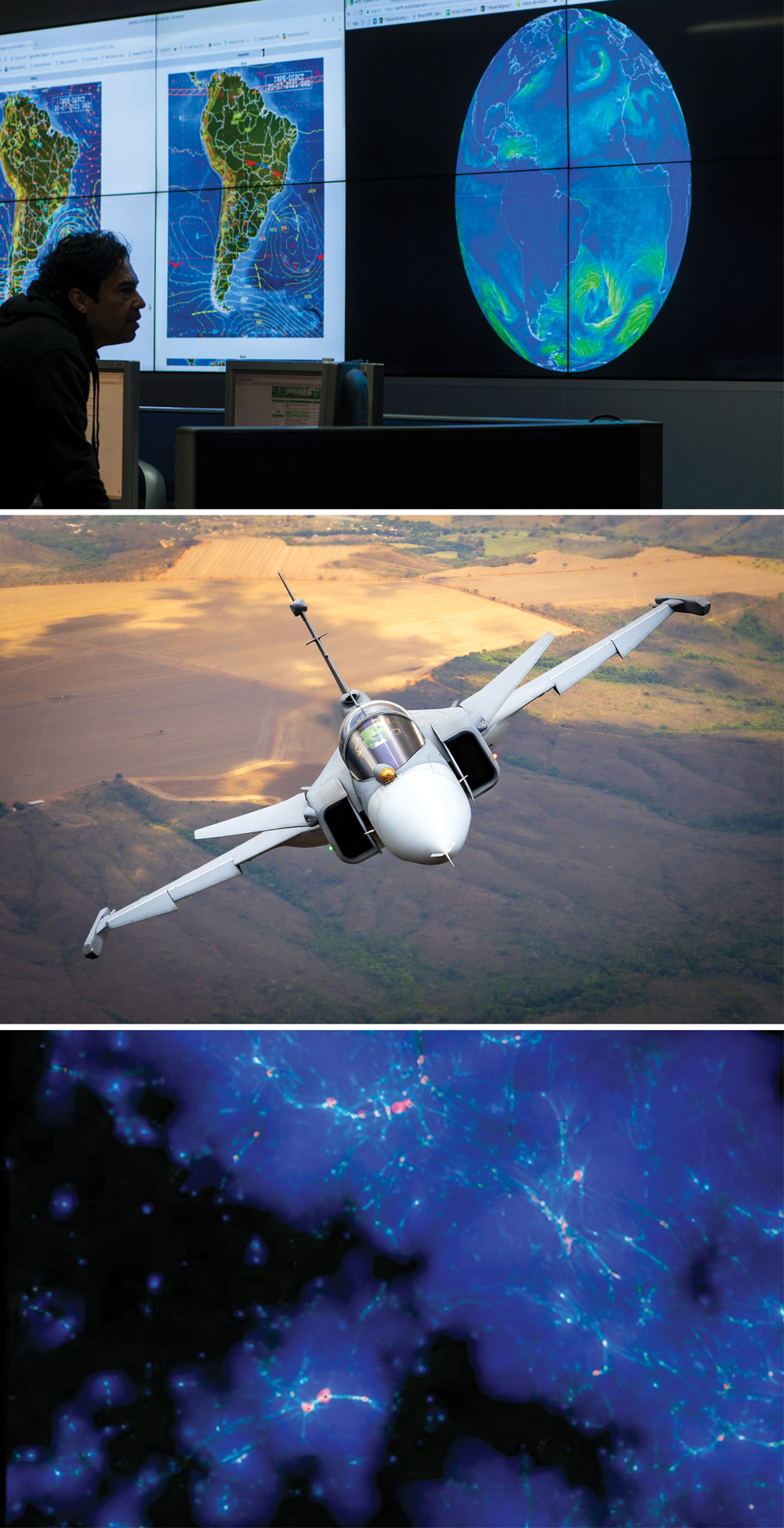

They can support research in many ways, from simulating the formation of the Universe to provide a better understanding of its evolution to molecular modeling to aid in the search for new drugs and forecasting extreme weather events. They are also used to expand the frontiers of oil and gas exploration, carry out research into new materials, develop aerospace projects, and investigate the potential of renewable energy sources.

Léo Ramos Chaves/Pesquisa FapespTechnician Ruy Marvulle Bueno configures UNICAMP’s Coaraci supercomputer to make it available to usersLéo Ramos Chaves/Pesquisa Fapesp

“With the growing use of AI in economic and social activities, the need for supercomputers capable of efficiently dealing with large volumes of data and offering quick responses to demands will continue to increase,” says Paulo José da Silva e Silva, a computer scientist from UNICAMP’s Institute of Mathematics, Statistics, and Scientific Computing (IMECC).

This year, the LNCC plans to increase the computing power of Santos Dumont, a machine dedicated exclusively to academic research, making it the most powerful computer in the country. SDumont, as it is better known, currently has a computational capacity of 5.1 petaflops. After the upgrade, it will be somewhere between 22 and 25 petaflops. The word flop is an acronym for floating-point operations per second.

One petaflop represents the capacity to process 1 quadrillion (1015) floating-point operations per second. SDumont, therefore, can process 5.1 quadrillion mathematical operations in just 1 second. To achieve the same feat on personal computers would require 24,500 devices working together.

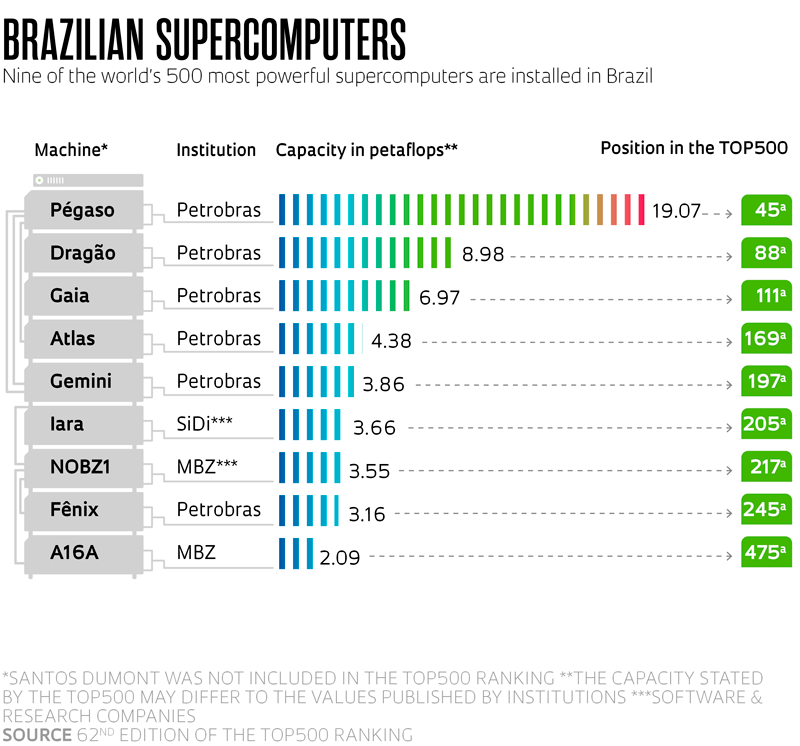

The largest supercomputer in Latin America today is Petrobras’s Pégaso, acquired from French company Atos for R$300 million in 2022. It went into operation in December of the same year, with a processing power of 21 petaflops. It placed 45th in the latest TOP500 ranking of the most powerful supercomputers in the world, released in November 2023.

The 62nd edition of the list, which started in 1993, was drawn up by researchers from the University of Tennessee, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the US National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC).

Brazil has nine supercomputers on the list — its best performance since 1993, when the TOP500 was first created — and ranks 11th among the nations with the largest supercomputer facilities. Petrobras owns six of these machines. Of the remaining three, two belong to software company MBZ — the NOBZ1 and A16A, both using Lenovo architecture — and one belongs to software and research company SiDi. The latter, named Iara, is based on Nvidia technology and is primarily used for AI research. For technical reasons, Santos Dumont was not included in the list, which only considers supercomputers with a homogeneous computational architecture (meaning all the computational nodes have the same configuration). This is not the case with the LNCC machine, which has four distinct architectures working alongside each other.

The list is topped by Frontier, the first exaflop supercomputer, which is capable of processing one quintillion operations per second and is based at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the USA.

Petrobras will be responsible for the budgeted investment of around R$100 million for the SDumont upgrade. “We expect the updates to be completed between July and August,” says mathematician Wagner Vieira Léo, head of information and communication technology at LNCC.

Felipe Gaspar / PetrobrasPetrobras’s Pégaso: operating since 2015, it is the largest supercomputer in Latin America and the 45th most powerful in the worldFelipe Gaspar / Petrobras

Milestone in scientific output

SDumont began operating in 2015 and was the first computing facility in the country with a capacity of over one petaflop — at the time, it was 1.1. In 2019, it was reconfigured to 5.1 petaflops with support from the Libra oil consortium, led by Petrobras. It functions as the central node (Tier-0) of the National High-Performance Processing System (SINAPAD), composed of nine HPC units linked to the MCTI.

As of December 2023, SDumont had been used in 430 research projects, resulting in 1,044 scientific articles, 43 books or book chapters, 398 master’s dissertations and doctoral theses, and 11 patents. It currently has more than 2,000 active users. “Santos Dumont represents a milestone in Brazilian scientific output. Before it began operating, researchers had to establish international partnerships to carry out this kind of work,” says Léo.

The supercomputer’s recent contributions include the sequencing of 19 coronavirus genomes, a task completed in 48 hours by researchers from the LNCC, the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) in March 2020, just one month after the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Brazil.

It was also used by scientists from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Pernambuco (FIOCRUZ Pernambuco) to develop a vaccine candidate for the Zika virus. Teams from the Heart Institute (InCor) at the University of São Paulo (USP) School of Medicine and the LNCC’s Hemodynamic Modeling Laboratory (HeMoLab) used it to create computational models that simulate blood flow in coronary arteries in order to diagnose heart attack risk.

“High-performance computing is now involved in almost all areas of scientific research. Even in the humanities, advanced data analysis is used to support public policy decisions,” explains IMECC’s Silva, who is also head of the National Center for High-Performance Processing in São Paulo (CENAPAD-SP), one of the HPC structures that make up the SINAPAD.

The São Paulo–based center is home to the Lovelace supercomputer, purchased in 2021 with aid from the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP) and upgraded in 2023 with funding from FAPESP. Named after English mathematician and computing pioneer Ada Lovelace, the machine, made by Dell Technologies, currently has a processing capacity of 388 teraflops. Each teraflop represents 1 trillion operations per second. The facility has another supercomputer called Tyr, which uses the IBM Power 750 system and has a capacity of 37 teraflops. In total, the center’s equipment provides 425 teraflops of processing power.

Between CENAPAD-SP’s inauguration in 1994 and the end of 2023, research carried out at the center had resulted in 4,400 published academic articles, 294 doctoral theses, and 331 master’s dissertations. There are currently 221 active projects and 737 users across the country. “The infrastructure is 100% occupied and there is a long waiting list,” says Silva.

He and Léo from the LNCC share the view that after the SDumont upgrade, the biggest priority for high-performance computing for academic research in Brazil is to update the infrastructure at other SINAPAD units, since all are facing greater demand than their processing capacity can handle.

The first reinforcement was made in January this year. The new Coaraci (meaning “mother of the day” in Tupi) supercomputer at CCES-UNICAMP was tested in December 2023 and made available to the academic community the following month. It is an 801 teraflops Dell machine, acquired with financial support from the Center for Engineering and Computational Sciences (CECC), one of the Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs) funded by FAPESP.

“It is the most powerful computer at a Brazilian university and will host research in a diverse range of fields of scientific interest. Our preliminary assessment is that Coaraci will be heavily occupied, 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” says mechanical engineer William Wolf, technical advisor at CCES. The equipment is installed at the John David Rogers Computing Center, part of UNICAMP’s Gleb Wataghin Institute of Physics.

Wolf, who is also head of UNICAMP’s Aeronautical Sciences Laboratory, believes Coaraci will allow Brazilian scientists to do studies that were previously not possible. Aerospace research carried out at UNICAMP, for example, uses supercomputers in the USA and France, in a process that takes an average of six months due to long waiting times and the bureaucracy of preparing and reviewing international proposals. Furthermore, these projects have to join a global waiting list and the results often need to be shared with foreign groups before being processed.

The Cosmic Dawn Project | INPE | Brazilian Air ForceSupercomputers are fundamental to research through simulations of the formation of the Universe (above), weather and climate forecasting, and aeronautical studies (below)The Cosmic Dawn Project | INPE | Brazilian Air Force

“The data are extremely difficult to obtain, and our primary interest is to process it. In some cases, the data may even be sensitive, involving technological innovations,” explains Wolf. “With Coaraci, we can carry out research locally, quickly, and safely, and without the need to share data, which in many cases will be beneficial to Brazil’s technological development.”

The INPE, another SINAPAD institution, is beginning a tender process for the acquisition of a new supercomputer capable of improving climate forecasting in Brazil. The institute plans to invest R$200 million from the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT). The money will be spent on computing and physical infrastructure for the INPE facilities in Cachoeira Paulista, São Paulo, to ensure the supercomputer has all the support it needs.

“The investment will be made in stages, starting this year and finishing in 2027,” explains space engineering and technology PhD student Ivan Márcio Barbosa, head of data infrastructure and supercomputing at INPE.

The first phase has a planned budget of R$47.5 million to purchase equipment that will generate a computing power of approximately 2 petaflops. At the end of the process in 2027, the new high-performance system will have a computing capacity of 8 petaflops, around 15 times greater than the INPE’s current supercomputer Tupã, which was purchased in 2010 and has 550 teraflops.

Supercomputers use a lot of electricity to run and to keep cool. Tupã costs R$4.8 million in electricity per year, says Barbosa. Like most supercomputers, its cooling system involves a combination of air conditioning and water — with 40,000 liters circulating in a closed circuit. The INPE plans to install a 138-kilowatt peak (kWp) electricity substation for the new supercomputer, as well as renovating its electrical, air conditioning, and treated water infrastructure. It also intends to build a photovoltaic solar power plant with an initial capacity of 300 kWp.

The upgraded climate forecasting system will include a new numerical weather and climate forecasting model called MONAN (model for ocean and atmosphere prediction), which is still under development. According to preliminary information shared by the INPE, in addition to traditional methods based on solving physical equations, MONAN will use AI and machine learning to predict the beginning and end of rainfall and extreme weather events three days in advance and to forecast climate change trends three months in advance. “We currently make forecasts for the following 15 days, but the accuracy is only high (around 90%) for the next 48 hours. Beyond seven days, it is below 50%,” says Barbosa.

Tupã will not be deactivated. “As long as the necessary parts remain available, the machine will be dedicated to scientific research projects in weather and climate,” says the researcher. This task is currently performed at the INPE by a high-performance processing cluster — a set of smaller computers used together to achieve a certain processing capacity. The Aegeon cluster at the INPE has a computational power of 200 teraflops.

The arrival of Gaia

The high-performance infrastructure for research in Brazil was further reinforced in 2023 with Petrobras’s R$76-million acquisition of Gaia, a 7.7-petaflop supercomputer made by Dell. Gaia began operating in August last year and is used exclusively by Petrobras’s Research, Development, and Innovation Center (CENPES). It will be used to develop and improve geophysics technologies, including seismic image processing tools, which use reflected sound waves to create a computed tomography of the Earth’s subsurface.

At the end of 2022, Petrobras had a processing capacity of 63 petaflops and announced its goal of reaching 80 petaflops, without specifying a date by which it plans to achieve this target. In addition to Gaia, the 3.9-petaflop Gemini also came into operation in 2023. In the production sector, the oil company’s supercomputers are mainly used for seismic data processing and reservoir engineering. In the former, the objective is to determine the presence of oil and the best areas for drilling; in the latter, the purpose is to study the behavior of stored oil.

Inside a supercomputer Equipped with thousands or even millions of high-performance processor cores, the machines can weigh between 20 and 40 tonsHigh processing speeds and large memory capacities are the two main characteristics of supercomputers. They are composed of a group of machines that work together, weighing an average total of 20 to 40 tons. The equipment is installed in rows of racks in a large, cooled space. Frontier, the most powerful supercomputer in the world, occupies 74 racks in a room measuring 680 square meters.

Santos Dumont, a supercomputer at Brazil’s National Laboratory for Scientific Computing (LNCC), is located near Rio de Janeiro in the city of Petrópolis, which has a mild climate but still requires three 750-kilovolt-ampere (kVA) generators — two in operation and one backup. The system uses 1,500 kVA just to run and keep cool.

The processing speed of a supercomputer is determined by how quickly it performs floating-point operations (flops). Today’s most powerful machines perform operations in the range of tens or hundreds of petaflops — one petaflop is equivalent to 1 quadrillion (1015) mathematical operations per second — or in exaflops, each of which represents 1 quintillion (1018) mathematical operations per second.

To achieve this feat, supercomputers have thousands or millions of high-performance processor cores, including central processing units (CPU) and graphics processing units (GPU). With a computational capacity of 5.1 petaflops, Santos Dumont has 36,472 CPU cores and 1,134 computational nodes.

The volatile memory or RAM (random access memory) of a personal laptop ranges from 2 to 32 gigabytes (GB). On a supercomputer, it is measured in terabytes (TBs, each of which is equivalent to a thousand GBs). Petrobras’s Pégaso, with 21 petaflops of processing capacity, has 678 TBs of RAM.

São Paulo to open new high-performance computing center Consortium of seven universities will have a 5-petaflop supercomputerA new supercomputer with a capacity of around 5 petaflops is set to begin operating in Brazil within the next year. The machine will be installed in the recently inaugurated São Paulo State Scientific Supercomputing Center (C3SP), one of the two centers awarded funding for high-performance computing by FAPESP, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI), and the Ministry of Communications (MCom).

“This is a long-standing demand from the state’s research institutions, which account for around 60% of the use of Santos Dumont, the LNCC’s supercomputer,” says meteorologist Pedro Leite da Silva Dias, executive director of C3SP. “If we want the research we do here to have a greater impact, we need more competitive machines.”

The C3SP is formed by the three state universities in São Paulo (USP, UNICAMP, and UNESP), the state’s four federal universities (UFABC, UFSCar, UNIFESP, and ITA), and two private institutions: FEI and Mauá. “A tender process for purchasing the equipment and selecting the data-processing center where it will be installed will begin soon. We chose a neutral location so as not to distort the concept of the consortium,” explains Dias.

The second project funded was the National Center for High-Performance Computing, part of the SINAPAD High-Performance Processing System. “Our project is part of an important moment for supercomputing in Brazil: the revitalization of SINAPAD,” says Antônio Tadeu Gomes, executive coordinator of the project and a researcher at LNCC.

The funding of approximately R$50 million, the same amount allocated to the C3SP, will be used to update five SINAPAD units: the National Supercomputing Center at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, the High-Performance Computing Center at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, the Digital Metropolis Institute at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, and the National Centers for High-Performance Processing in Minas Gerais and Ceará.

The combined computing power of the five centers is currently close to 700 teraflops. After the upgrades, it is expected to be between 4 and 8 petaflops. “These centers will support scientific research in different regions of the country,” highlights Gomes.

Republish