Daniel AlmeidaThe flow of translations and the circulation of books by Brazilian authors abroad shows that Brazil’s literary system was built in dialogue with cultural traditions of other countries. That was one of the conclusions of the research study Brazilian literature and transnationalities: Displacements, identities and experiments in technology, which sought to map the Brazilian writers most translated into English from the 19th century through 2014. Researcher Cimara Valim de Melo, a professor at the Federal institute of Education, Science and Technology of Rio Grande do Sul (IFRS), Canoas campus, determined that travelers and naturalists were responsible for undertaking the initial efforts of translation into English. The study, published in the journal Modern Languages Open, shows that the process went through a phase of limited activity until 1940 when it gradually began to increase, driven by interest on the part of foreign readers in experiencing literary themes permeated by exotic images.

Daniel AlmeidaThe flow of translations and the circulation of books by Brazilian authors abroad shows that Brazil’s literary system was built in dialogue with cultural traditions of other countries. That was one of the conclusions of the research study Brazilian literature and transnationalities: Displacements, identities and experiments in technology, which sought to map the Brazilian writers most translated into English from the 19th century through 2014. Researcher Cimara Valim de Melo, a professor at the Federal institute of Education, Science and Technology of Rio Grande do Sul (IFRS), Canoas campus, determined that travelers and naturalists were responsible for undertaking the initial efforts of translation into English. The study, published in the journal Modern Languages Open, shows that the process went through a phase of limited activity until 1940 when it gradually began to increase, driven by interest on the part of foreign readers in experiencing literary themes permeated by exotic images.

Melo began studying the process of internationalization of Brazilian literature during postdoctoral research at the Brazil Institute of King’s College London based on groundbreaking research by translation studies researcher Heloisa Gonçalves Barbosa, a retired professor from the School of Letters at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), conducted for her doctoral dissertation defended in 1994. In that study, the Rio researcher obtained information about Brazilian works translated into English from 1500 to 1994. “Heloisa did that mapping before the Internet was even available to most people, which led her to exchange correspondence with editors and conduct in-person interviews,” says Melo who also used information from the Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, which catalogues literary works translated into English and serves as a reference for translators. She accessed information from publisher’s websites, literary festivals and book fairs. The data collected is stored on the Richard Burton platform (richardburton.canoas.ifrs.edu.br), which offers an index of full translations of Brazilian literature into English.

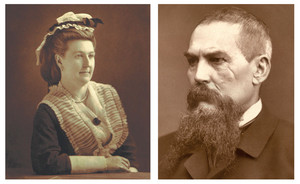

Richard Burton, British explorer and diplomat who served as consul to Brazil from 1865 to 1869, along with his wife, Isabel Burton, were the first translators of Brazilian literature into English. Isabel translated Iracema, a book by José de Alencar, under the title: Iracema the honey-lips: A legend of Brazil. In the same year, Richard Burton translated Manuel de Moraes: Crônica do século XVII, by João Manuel Pereira da Silva, published under the title Manuel de Moraes: A chronicle of the seventeenth century. In these works, Melo says that the translators placed emphasis on the indigenous culture and natural landscapes, exploring images of a diverse and exotic country. “Burton disseminated local literature in the anglophone world, at a time when post-independence Brazil was looking to build its national cultural identity,” she explains.

Valéria Cristina Bezerra, an expert in literary theory and history, and the author of the thesis entitled José de Alencar and the tension between domestic and foreign in the making of Brazilian literature, defended at the University of Campinas (Unicamp) in 2016, explains that Isabel Burton’s translation of Iracema was published by a publishing house aimed at England’s elites. “In his writings, Alencar linked foreign and domestic elements and behaved in a way that integrated Brazilian literature into the international experience,” she says. When looking at Brazilian literature, she says foreign readers searched for picturesque and exotic elements, displaying a preference for works that depicted indigenous reality and the exuberance of Brazil’s natural landscape, as is the case with some of Alencar’s works.

In the 40 years that followed the pioneering work of the Burtons, occasional translations were done during a period of less transit in Brazilian literature into other languages. Translations into English did not increase in number until after 1940, when British publishers Macmillan and Arco Publications discovered part of Brazil’s literary canon. According to Melo, the dearth of translations from the first half of the 20th century is related, among other domestic and international aspects, to the absence of public policies to promote circulation of Brazilian works abroad.

British library / Wikimedia commons | Men of Mark / Wikimedia Commons

The British Isabel and Richard Burton are said to have been the first translators of Brazilian literature into EnglishBritish library / Wikimedia commons | Men of Mark / Wikimedia CommonsLatin american novels

There was a growing interest on the part of Europe and the United States for Latin American novels starting in the 1950s. During that period, American and British universities established Brazilian Studies Departments which led to an increase in the number of translations. “As a result of these efforts, some 39 works were translated during the 1970s and 56 titles in the 1980s. In the later decades of the 20th century, an average of only 20 books were translated,” Melo says, by way of comparison. Antonio Callado, Lêdo Ivo, Lygia Fagundes Telles, Moacyr Scliar and João Ubaldo Ribeiro were some of the authors most frequently translated during the 1970s and 1980s.

In the first half of the 20th century, translations into English were occasionally done by editors or scholars of Brazilian literature. During the post-war period, however, translations began to be done primarily by professionals associated with universities. That was the case with Machado de Assis, whose first translation into English appeared only in 1952. Entitled Epitaph of a small winner, the book Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas came out first in the United States before it was published in the UK in 1953. Jorge Amado, on the other hand, achieved success among the US public from the time his first work—Terras do sem fim—was translated in 1945 as The violent land, and he went on to be translated into 50 other languages in the years that followed. Melo attributes this interest to the exotic environment depicted in the writer’s stories, which also allowed foreign readers to learn about the dynamics of social exclusion from Brazilian society.

In studying works translated into English from the 1990s through 2014, Melo notes the existence of three parallel phenomena. The first is Paulo Coelho, an author whose books have been translated into 70 languages and who has sold 200 million copies, attaining a stature in the international cultural market matched only by Jorge Amado. The second phenomenon was the re-translation of works by Clarice Lispector, edited by U.S. writer and historian Benjamin Moser, who also wrote Lispector’s biography, enabling her repositioning on the world literary stage. Linguist Lenita Maria Rimoli Esteves, a professor at the USP School of Philosophy, Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH-USP), notes that Moser promoted a new image of the author. “The U.S. public was attracted to the Jewish immigrant who experienced family tragedy; and that helped promote interest in the books,” Esteves says.

Efforts by international literary agents and publishing houses as well as authors’ appearances at literary events and book fairs represents the third phenomenon behind the increase in the volume of translations of contemporary Brazilian authors, who had begun to address more universal themes, less associated with the notion of national identity, thereby increasing interest in their stories on the part of the international public. According to Melo, from 2010 to 2014, 27 new translations were done, driven in part by the program established by the National Library in the 1990s that offers, among other initiatives, foreign publishers financial support for translations of Brazilian works

Melo believes ebooks also helped promote new translations of Brazilian literature into English, given their ease in purchase and reading. Maria Eduarda Marques, director of the Center for Cooperation and Diffusion at the National Library, says that Clarice Lispector, followed by Machado de Assis, is the author most translated into other languages through the program which has now funded the translation of over 900 titles.

UH Collection / Folhapress

Clarice Lispector autographing a book in 1961: a 2009 biography repositioned her work abroadUH Collection / FolhapressFrance

Before pursuing the anglophone market, the goal of Brazilian writers had been to be published and read in French. In the transit of Brazilian authors to Europe, Valéria Cristina Bezerra highlights the role some literary agents played in promoting Brazilian works in France between the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, as it appeared in documents of that time, among which is a receipt on which José de Alencar requested payment to Adolphe Hubert, mentioned on the receipt as responsible for a French translation of O Guarani, from French publisher Baptiste-Louis Garnier (1823-1893). “Collaboration occurred among people from different nationalities and roles in seeking to promote and recognize Brazilian literature abroad,” says Bezerra who is now doing a postdoctoral internship about Garnier at the Institute of Biosciences, Letters and Exact Sciences at São Paulo State University (Unesp), São José do Rio Preto campus. The editor thus facilitated the promotion of Brazilian literature in Europe in addition to publishing French authors in Portuguese.

Alencar had a few of his works partially translated into French beginning in 1863, but his first novel to be fully translated in France was not released to the public until around the turn of the 20th century, the same time works by Visconde de Taunay and Machado de Assis were published. O Guarani, by Alencar, was translated under the title Les aventuriers ou le Guarani, and published in serial form in 1899 and later as Le fils du soleil, in 1902.

Ilana Heineberg, a professor at France’s Université Bordeaux Montaigne says that in the preface to Le fils du soleil, translator Xavier de Ricard emphasized the fact that the book merged the notion of Latin-ness with the indigenous origins of Brazil. Heineberg says that there had been a preference for translating Alencar over other writers because of the exotic nature of his work. “When Adrien Delpech first translated Machado de Assis into French in 1908, he pointed out the Brazilian writer’s proximity to French intellectuals and lamented that absence of ‘local color’ on the part of the author,” she reports.

Scientific articles

MELO, C. V. de. Mapping Brazilian literature translated into English. Modern Languages Open. p. 1-37. 2017.

MELO, C. V. de. Border crossing in contemporary Brazilian culture: Global perspectives from the twenty-first century literary scene. Brasiliana – Journal for Brazilian Studies. V. 4, No. 2, p. 579-605. 2016.

Thesis

BARBOSA, H. G. The virtual image: Brazilian literature in English translation. University of Warwick. 1994.