Congressional amendments—a mechanism through which deputies and senators allocate part of the federal budget toward commitments made to state and municipal governments and institutions—have increasingly become an added source of funding for Brazil’s universities. Amendment funds have been used for everything from research grants to building upkeep and major infrastructure works, including new laboratories. The surge in such allocations mirrors a broader expansion of federal budget amendments and has sparked debate among higher-education experts: while on the one hand, the extra funds can help fill gaps in universities’ budgets, on the other, these transfers can be unpredictable—funds may flow one year and vanish the next—and should not be seen as a replacement for long-term, reliable public funding.

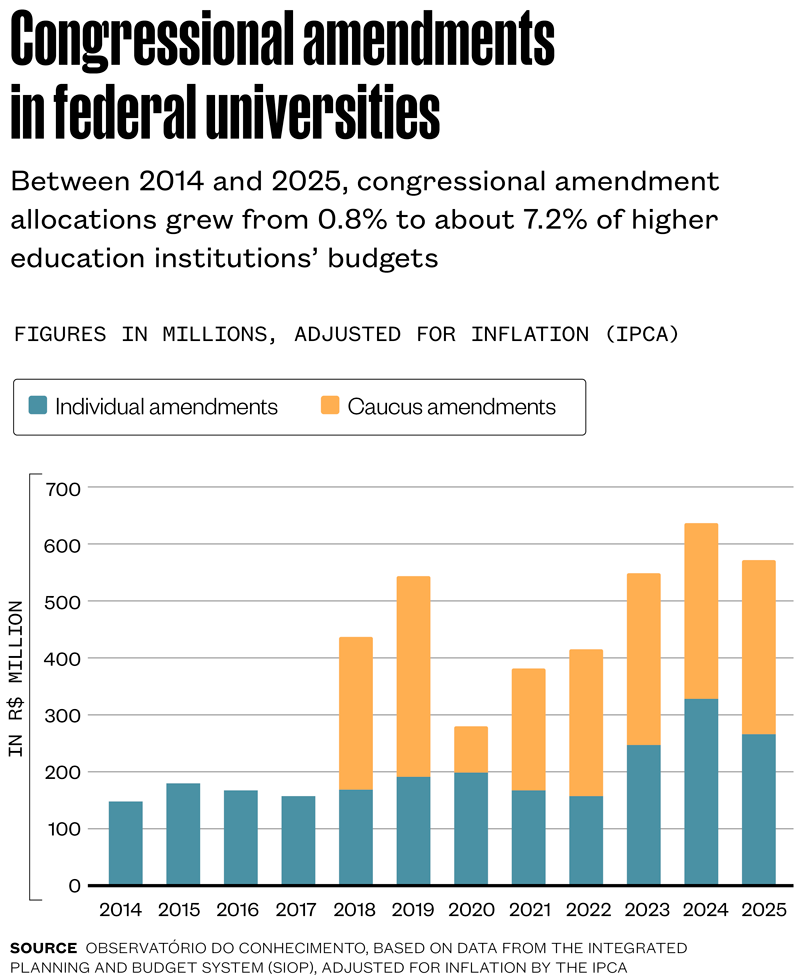

Between 2014 and 2025, the share of universities’ budgets funded through congressional amendments jumped from 0.8% to about 7.2%. This year, Brazil’s 69 federal universities are slated to receive R$7.89 billion under the Annual Budget Law (LOA), with R$571 million coming from lawmakers’ amendments. Although slightly lower than in 2024, the numbers reflect steady growth over the past decade—in 2014, universities received just R$148.42 million through amendments, at a time when their discretionary budget under the LOA was about R$17 billion—more than double today’s level.

The numbers are from a report released in August by Observatório do Conhecimento, a think tank tied to public-university faculty unions. The data were drawn from the Ministry of Planning’s Integrated Planning and Budget System (SIOP). It’s worth noting that these figures reflect only the initial allocation approved in the Annual Budget Law (LOA), not the funds actually disbursed or fully spent.

“As the Ministry of Education’s budget disbursements have shrunk, universities have leaned on congressional amendments as a stopgap. But these funds are nowhere near enough to address the challenges facing universities, which in recent years have expanded enrollment and opened their doors more widely through affirmative-action programs,” says political scientist Mayra Goulart da Silva, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) who heads the think tank. “On top of that, budget amendments are hostage to political winds, and there’s no guarantee they’ll continue from one year to the next.”

Economist Letícia Inácio, who leads research at Observatório do Conhecimento, notes another trend: “An ever-growing share of public money in Brazil is being funneled into these amendments.” Inácio has authored two studies on the subject, the first in 2023, which already showed universities’ rising dependence on this form of funding. In 2025, the government has earmarked R$50.4 billion for congressional amendments, up from just R$9.6 billion in 2014. “This kind of funding shifts new burdens onto university leadership and research groups, who now have to engage in political negotiations with lawmakers—something that wasn’t part of their role before,” she points out.

This year, Brazil’s federal universities are projected to receive R$302 million through caucus amendments—funds directed collectively by lawmakers from the same state to a given institution—and another R$269 million from individual amendments made by single members of Congress.

“Congressional amendments, once limited to one-off projects like outfitting museums, are now being used to cover essential needs,” says biomedical scientist Helena Nader, chair of the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC). “The concern is that these funds, which should be supplemental, are increasingly substituting for funding that ought to be guaranteed by law,” she warns.

In 2024, Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court (STF) temporarily froze these legislative allocations to review transparency standards—a review that extended to public universities. In January 2025, the Court ordered federal and state governments to issue, within 30 days, clear rules for how universities and their supporting foundations—nonprofit entities that often manage amendment funds—must report their use of allocated funding.

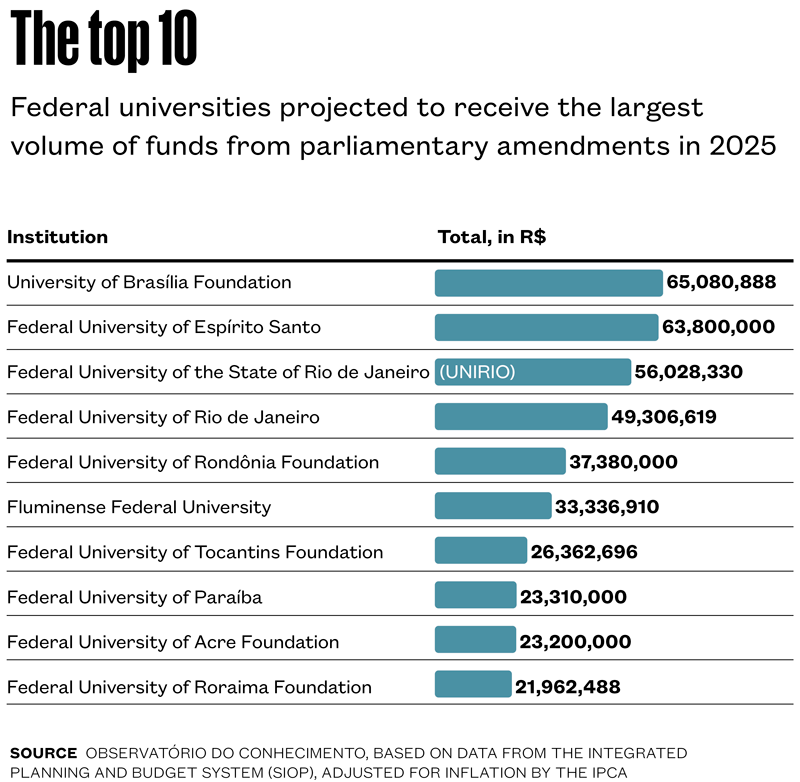

“One of the Court’s requirements was that supporting foundations publicly disclose the projects funded with amendments,” notes economist Letícia Inácio. As a result, in February the Ministry of Education (MEC) issued new regulations detailing how federal universities and their foundations must use and account for this money. Inácio also identified the ten federal universities slated to receive the most amendment funding this year. Leading the list is the University of Brasília Foundation at R$65.08 million, followed by the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) at R$63.8 million and the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO) Foundation at R$56 million (see chart).

Uses of amendment funding

In a 2023 article in the journal Práticas em Gestão Pública Universitária, researchers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and Fluminense Federal University (UFF) reported that between 2019 and 2022, UFF received R$132.72 million through both individual and caucus amendments. The university is also among the ten institutions projected to receive the most amendment funding in 2025.

Most of the funds (76.8%) went to campus restructuring and modernization projects, such as building renovations and upgrades. Another 12.4% supported undergraduate, research, outreach, and graduate programs, while 10.8% was spent on operational needs, including furniture and equipment purchases and payments to contractors. The findings were based on data from Tesouro Gerencial, the Federal Government’s budget-tracking system.

“At UFF, one major challenge was resuming construction projects launched under the Restructuring and Expansion of Federal Universities (REUNI) Program—which had been frozen since 2013,” says university-administration specialist Gisele Fernandes, a staff member in UFF’s Planning Office and lead author of the study. “Thanks to the budget amendments—particularly the caucus ones—we managed to pull together larger funding packages, complete unfinished buildings, and equip laboratories,” she explains. Fernandes is currently on secondment at the Benjamin Constant Institute, where she serves as director of Planning and Administration.

One of the examples highlighted in the study was the resumed construction on UFF’s new School of Medicine building in 2019. The project had stalled for lack of funding but was revived with about R$25 million from a caucus amendment, secured through negotiations by the university’s senior leadership. The building was finally completed in December 2024.

“Amid repeated budget cuts, amendments have taken on a strategic role as tools of institutional resilience and a way to keep infrastructure and long-term projects moving forward,” says Fernandes. In 2024, she organized a budget forum at UFF to discuss best practices in managing amendment funds with faculty, staff, and students. In June 2025, the university issued new regulations, a practical handbook, and an interactive online dashboard showing in detail how amendment money is spent.

Elsewhere, between 2016 and 2023, Brazil’s four federal rural universities used most of their individual amendment funding for campus restructuring and upkeep. Smaller shares went to teaching, research and outreach programs, and student support initiatives such as need-based retention scholarships, according to a July 2024 article in the journal Revista Jurídica da UFERSA.