Léo Ramos ChavesFor more than two decades, Carlos Alfredo Joly’s name has been directly associated with the FAPESP Biota Program, which has been recording animal and plant species in the state of São Paulo and Brazil since March 1999. A founder and one of the main leaders of the initiative—which includes around 300 projects, both completed and in progress, and employs 1,200 researchers—the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) botanist proudly speaks on the contributions of the program to the formulation of public environmental policies and the training of human resources (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 298). His voice becomes almost angry, however, as he stresses that, despite all efforts, the biodiversity of São Paulo is in an even more critical state than it was 20 years ago. “It has been neglected,” he says.

Léo Ramos ChavesFor more than two decades, Carlos Alfredo Joly’s name has been directly associated with the FAPESP Biota Program, which has been recording animal and plant species in the state of São Paulo and Brazil since March 1999. A founder and one of the main leaders of the initiative—which includes around 300 projects, both completed and in progress, and employs 1,200 researchers—the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) botanist proudly speaks on the contributions of the program to the formulation of public environmental policies and the training of human resources (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 298). His voice becomes almost angry, however, as he stresses that, despite all efforts, the biodiversity of São Paulo is in an even more critical state than it was 20 years ago. “It has been neglected,” he says.

One strategy to leverage the conservation of species is to associate the preservation of biodiversity with the fight against climate change—two contemporary issues that, in his view, must go hand in hand. Joly is part of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), an international biodiversity initiative that works much like the IPCC, the climate panel. He is also one of the leaders of the Brazilian Platform of Biodiversity and Ecosystems (BPBES).

In the following interview, Joly speaks on biodiversity and Biota, and he recalls his childhood and youth spent in a near-rural area on the west side of the city of São Paulo—the region around the Pinheiros River, before the construction of the eponymous highway. He also recalls his frequent road trips to the north coast of São Paulo and other parts of Brazil alongside his father, botanist Aylthon Brandão Joly (1924–1975), who was a professor at the University of São Paulo (USP). Joly has two grandchildren and two daughters—a geographer and a journalist—from his first marriage. His journalist daughter is planning on opening a plant store. “Our family’s relationship with botany and the environment will go on for at least another generation,” he adds.

Area of expertise

Plant ecophysiology and biodiversity conservation

Institution

University of Campinas (UNICAMP)

Education

Undergraduate degree in biology from the University of São Paulo (1976), master’s degree in plant biology from UNICAMP (1979), and PhD in plant ecophysiology from University of St. Andrews, Scotland (1982)

Published works

129 scientific articles, 15 books as an author or editor

What do you think about the state of biodiversity in the state of São Paulo and in the country compared to when Biota was first founded?

Last year, as a celebration of the twentieth anniversary of Biota, we held several meetings on different topics. In terms of biodiversity, we arrived at the conclusion that the state of São Paulo is worse off than it was 20 years ago. It has been neglected, but we also agreed that it would be in a much worse state without Biota. We continue to have major issues involving the excessive fragmentation of native vegetation areas. Very few fragments of the Cerrado [wooded savanna], for example, are large enough to house mammal populations, such as the maned wolf or the anteater. The state is losing its ability to conserve these animals. We still have a good amount of Atlantic Forest remnants left, but many areas are poor in terms of fauna. Hunting was never effectively controlled in these places. Many studies show that the absence of small rodents, which are very important for seed dispersal, affects the regeneration forest dynamics. While we have had some advances, the state government shows no concern at this time. Today, we know that the biodiversity and climate change agendas are inextricably linked.

Could you give an example?

The restoration of forests could offset part of the CO2 [carbon dioxide] emissions, the main greenhouse gas that causes global warming. The state could intensely promote this policy. Through the actual enforcement of the forest code, we could make sure 20% of rural properties remain legal reserves and permanent preservation areas. But the abusive use of the compensation mechanism in deforested areas cannot be allowed to continue. If a deforested legal reserve area is located in São Paulo, in the Atlantic Forest biome, its environmental compensation should take place within the state of São Paulo, not in a far-away state like Piauí, even if it is technically within the same biome. That might be good for Piauí, but it does nothing for São Paulo. We continue to have little vegetation. It sounds unbelievable, but many public administrators simply cannot understand that cyclical droughts are related to the destruction of vegetation cover. They think in terms of engineering solutions, like building more reservoirs so that there is no water shortage in a city. If only the forest code were enforced and the native vegetation were restored, the natural hydrological cycle could be reestablished, with better rainfall distribution throughout the entire state. We need these ecosystem services here. However, some landowners would need to give up areas that are currently used in agriculture for restoration. This would affect certain economic interests, but it is for the greater good, for the good of the entire state population.

Did the Biota studies have an impact on public environmental policies in recent years?

As I said, our situation would likely be worse without Biota, which has had and is having a big impact. But we have not been able to reverse the general state of things. This is quite clear to us. On the other hand, we have trained an army of researchers, of young PhDs, with the goal of collaborating in large, multidisciplinary teams, from different institutions and with diverse interests. These professionals will make all the difference going forward. In this aspect, Biota is a great success.

How has our knowledge about biodiversity changed in the last 20 years? Has there been any progress here?

Today we know more about our biodiversity and its current state, but most of our knowledge advances are around how ecosystems work. We can now model and predict the impacts of climate change on the Atlantic Forest or of the indiscriminate use of pesticides on pollinators, for example.

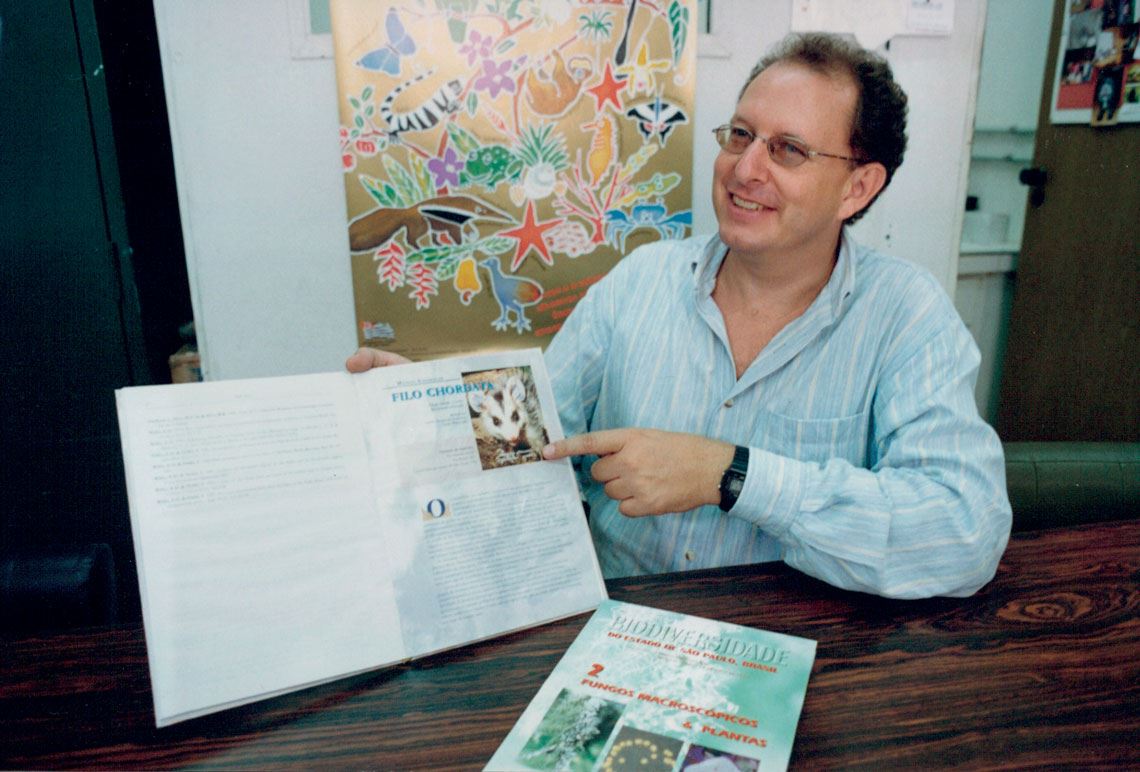

Personal archives

Joly in 1999, at the launch of the Biota programPersonal archivesAre lay people and growers receptive to this type of study?

If they feel the data is grounded in reality, they do accept it. This is not just speculation or idealism on our part. Landscapes are multifunctional. For example, maintaining at least part of a region’s native biodiversity increases pollination levels, which is good for agricultural productivity. A coffee field near a forest produces more beans than an isolated farm surrounded only by coffee plants. In the state of São Paulo, the economic impact is not strong because we are heavily dependent on sugarcane harvesting. But in soy-producing regions, this becomes more of an issue. In areas near conserved forests, soybean seeds are heavier, allowing growers to convert smaller areas and produce more. We have mapped the entire state in terms of where we could maintain legal reserves. We know that there aren’t enough Cerrado areas in São Paulo for environmental compensation. In this case, we recommend the the compensation be carried out in neighboring states, such as Minas Gerais, where the headwaters of our main rivers are located, which is important for our water supply. This policy is not very expensive. All we have to do is restore and preserve peripheral areas, which are generally low in agricultural productivity anyway.

Would you say that the shared agendas of biodiversity and climate change are beneficial to these two areas?

Generally speaking, yes. But our Ministry of Foreign Affairs holds the misguided position, not only in the current administration, that officially mixing these two agendas in international agreements is bad for Brazil in the medium and long term. They believe Brazil could face trade issues if it embraces the idea that climate change has a major impact on biodiversity. While there is much overlap, not everything applies to both biodiversity and climate change. Let me give you an example. In principle, planting forests is good for biodiversity and for fighting climate change. Permanent forests remove CO2 from the atmosphere. But we shouldn’t plant trees in the Pampas, a predominantly herbaceous biome. That would be very bad for the biodiversity of this ecosystem. It does not support trees. The right thing to do is to restore forests where there originally were forests. Many such decisions could help mitigate climate change but be harmful to biodiversity. This is why we need to look at the situation from all angles.

Do you agree with the assertion that the impact of the work carried out by the IPBES seems relatively modest when compared to that of the IPCC?

There have been other international biodiversity initiatives before the IPBES, but they ended up buried under bureaucracy. The IPBES was established by more than 100 nations in 2012, meaning we are younger and less well known than the IPCC, which was founded in 1988. Our first biodiversity report was released in May 2019. It’s true that we are behind when compared to the IPCC. But I would like to emphasize that Brazil’s scientific community has been very active in IPBES. We are the only nation that has representatives on all IPBES task forces and diagnostic report teams. The most recent report on biodiversity in the Americas involved around 25 Brazilian researchers—nearly a quarter of all its scientists. The first global report was led by a Brazilian scientist, Eduardo S. Brondizio, currently a professor at Indiana University, in the United States. Cristiana S. Seixas, from UNICAMP, who is part of the Biota research community, has helped lead the report on the Americas. The same happened with a pollination report, which was led by Vera Imperatriz Fonseca, from the USP Institute of Bioscience—another Biota researcher. We have been very active. This is why we have brought together Brazilian researchers, who have been working on these international reports, to establish the Brazilian Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, BPBES.

Many public administrators simply cannot understand that cyclical droughts are related to the destruction of vegetation

What has BPBES been up to?

In 2019, we produced the first diagnosis report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. We also produced thematic reports on forest restoration, pollination, and water. We are currently developing a report on agriculture, biodiversity, and ecosystem services; another on the coastal and marine region, the relationship between land and sea; and a third one on invasive species. These three new reports are currently underway and should be out in 2023 or 2024 at the latest. Our goal with these reports, and their respective Summaries for Decision Makers, is improving public policy on the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of biodiversity and ecosystem services, based on the best available scientific knowledge, as well as the knowledge of indigenous and traditional communities.

Nowadays, many claim that the future of some regions of Brazil, especially the Amazon, depends on developing the bioeconomy, or the wealth that derives from biodiversity. What do you think about this?

One of the issues with that idea is that there are many different concepts and definitions of bioeconomy. There is a lot of noise in this area. We know that the Amazon rainforest is worth much more standing than felled and transformed. But the question is how to turn this potential value into better economic and living conditions for Amazonian populations. They have their own cultures and have a right to efficient health care and education, as well as access to any consumer goods they may desire. When we, biodiversity scientists, think about the bioeconomy, we believe that paying for environmental services is one way to make this happen. There is a large experiment being carried out in the municipality of Extrema, on the border with the state of São Paulo, whose landowners are being paid to protect water resources. There is another, similar FAPESP-funded project under development in the Paraíba Valley. This is how we increase the value of the forest. What cannot happen is outsiders coming in, purchasing non-timber forest products at a ridiculously low price, and calling it a bioeconomy.

Are there any positive initiatives of the so-called bioeconomy?

The Amazon has a fantastic example: the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Institute, in the state of Amazonas. This project began with the development of fisheries management, especially of arapaima fishing, but it became much more. To limit the exploitation of the arapaima fish, the population’s income must be supplemented in other ways by diversifying their products—such as traditional crafted items. Then a question arises: can I extend this approach to other regions of the Amazon? There lies our main issue. While these experiments have worked at the local level, they are not replicable on a larger scale. We have been racking our brains in search of a way to make this approach actually work at other levels. Natura is a company that has a good system for the use of fruits, roots, and leaves for the cosmetic industry, and where the extraction of these resources is managed by local communities. It took them a long time to figure this out, as they had to plan their activities in such a way as to provide resources for the communities throughout the year. The Brazil nut, for example, bears fruit during a certain time of year. They need to ensure the population that lives off of the extraction of the nut will have another source of income for the rest of the year. Therefore, it is key to set up an arrangement that incorporates several different products and can guarantee their income throughout the year. It concerns me to hear talk that the bioeconomy will solve the issues of the Amazon. We cannot have a repeat of the açaí debacle—a product that is being overexploited in some parts of the Amazon. It is an excellent product that generates income for local populations. But we need more research on its harvesting in order to perhaps improve its production chain, cut out the middlemen, and establish local cooperatives and associations.

Understanding how our ecosystems work was Biota’s main contribution to our advance in knowledge

How has the pandemic affected the Biota projects and biodiversity research?

Projects that depend on field work, on collecting species, have been suspended. The conservation units themselves were closed by order of the state government and are now reopening. I predict we’ll be able to resume part of our field work, but there has obviously been a loss. For scientists whose work depends on observing nature cycles through periodic visits, the research protocols are being adapted. The pandemic has also hindered any work involving collections, as well as work done in laboratories, as access to these places has been restricted. We still haven’t fully assessed the impact, but the Biota leaders are working on it.

Does Biota have any projects on the issue of biodiversity and the emergence of new diseases from wild species, as seems to be the case with COVID-19?

The pandemic has brought about new frontiers, which our program has yet to explore. We have, at certain points, attempted to work on the interface between health and biodiversity, but this approach has never really worked for us. Some of our researchers study malaria, yellow fever, and disease vectors, and these partnerships need to be improved. But we don’t have any Biota projects on virus surveys, for example, regardless of their impact on human health. In our recent discussions, we raised this issue with the coordinator of an international project to study and map the distribution of viruses. We would like for Biota researchers to engage in this type of research. We need to study the potential connection between viruses and other pathogens and urban green areas, to predict the eventual emergence of health problems.

Let us go back to the beginning of your career. When did you first develop an interest in biology?

My father’s influence was certainly very strong in this regard, not only because of his career, but also because we used to go on road trips where he would always explain to me how important and unique different types of vegetation were, such as that found in forests, mangroves, or sand dunes. He was a biologist not only when teaching at the university, but also when teaching us about nature. I once had the opportunity to go on a bus trip with him to the Northeast, during which I learned so much. At the time, my father was very scared of planes. Thus, he would always prefer to travel by bus or car whenever he attended national botany conferences, held in a different city each time. When I turned 15, he allowed me to accompany him to a conference that took place in the city of João Pessoa. We travelled there and back by bus, alongside his students. I was also heavily influenced by the biology teacher Albrecht Tabor, from Colégio Visconde de Porto Seguro (a private school in the city of São Paulo), where I attended secondary school at the time. He was passionate about biology, much like my father. He was a fantastic teacher and, during his vacations, he would travel to places that seemed totally exotic to us at the time, like Australia and South Africa. When he returned from his trips, he would always give a lecture or two on the plants and animals he’d seen during his trip.

What was it like to grow up near the banks of the Pinheiros River before there was a highway there?

I used to live on the edge of the city—practically in the countryside. We had our milk delivered by a milkman, who used to arrive in a horse-drawn cart. The street where I lived, Rua Hungria, was paved for basically two blocks; the rest of it was dirt. There was a strip of wood across it, then the train tracks, and the Pinheiros river. Across the river, you could see the walls of the Jockey Club. My family witnessed the entire development of that region, right up until the Rua Hungria became the local lane of the Pinheiros highway. From an early age, I developed an interest in collecting animals. I had collections of spiders and scorpions, most of which I would capture near my home; later, I began collecting butterflies, most of which I would catch on the north coast of São Paulo. When I was little, I used to spend my vacations in Ilhabela, where my grandfather had a beach home. When I turned eight, my parents built a home on Lázaro beach in Ubatuba. In addition to spending our vacations there, we would go to Ubatuba every two weeks. My best friends were all locals there. With them, I would go out hiking, diving, spearfishing, play soccer, and collect butterflies. I liked to identify eggs or caterpillars at very early stages. I would take them home to raise so I had newborn butterflies for my collection, with perfect wings, without any scaling. My father taught me how to capture the animals, kill them, and later prepare them for a collection. I later donated all this material to the UNICAMP Museum of Biological Diversity.

Miguel Boyayan

The botanist at UNICAMP in 2004Miguel BoyayanWhen you were admitted into the biology program at USP, you were taught by your own father. What was that like?

My class was the last one to be taught by my father. I was a sophomore at university when he passed away. It was a very difficult time. My father found out he had cancer in April 1975 and passed away in August, just before his 51st birthday. In my first two years as an undergraduate, I helped lead the student union and my father was vice-director of the Institute of Bioscience. Occasionally, there was some unavoidable conflict between whoever was trying to run a teaching and research department and my group, who would stir up the students, disrupt classes, and distribute leaflets. But, overall, it was a very positive experience. My father would support our ideas, although obviously he didn’t always support how we went about implementing them. After he passed away, I decided to focus more on my studies. I had intended to graduate quickly and get a job. My worldview and the way I thought about the future changed a lot. I managed to take some night classes and catch up on some of the courses I had missed. In the end, I managed to graduate in four years, despite the mishaps at the beginning of the program.

Why did you leave USP to obtain your master’s degree at UNICAMP?

With the death of my father, my academic environment changed altogether. Certain people disappointed me very deeply. They seemed to be very good friends with my father but drifted away completely after his death. One exception was Professor Eurico Cabral de Oliveira Filho, who was one of my father’s students and remained a friend of the family. Given this environment, I thought it better to continue my education at UNICAMP, where there was no botany graduate program yet. I had been around during the early days of UNICAMP because my father had been asked to help establish the Department of Botany there. The UNICAMP Institute of Biology was limited to one room, where the General Board of Administration is now located. Thanks to my father’s influence, I knew the professors at UNICAMP. At a certain point, I asked Professor Gil Martins Felippe, whose field was plant physiology, to be my master’s advisor, and he said yes. We put together a project and submitted it to FAPESP. In the second semester of 1976, the Institute of Biology decided to implement a graduate program on plant biology. As I already had a project approved by FAPESP, I made some changes to the proposal and turned it into my master’s project. In two years, I finished my dissertation on the germination of Cerrado species. In August 1978, I was hired by the Department of Botany at IB/UNICAMP. I defended my master’s dissertation in June 1979; in September, I left to get my PhD at the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland. In October 1982, I returned to my department with a PhD.

What was your PhD research on?

The adaptation mechanisms of some Brazilian trees to periods of river flooding when there is water saturation in the soil. During flooding, there is no oxygen in the soil for the roots to breathe. Species that live in these environments develop specific adaptations to survive under these conditions.

But how did you study tropical trees in Scotland’s cold climate?

It wasn’t easy. I grew my seedlings and conducted the experiments in the tropical greenhouse at the St. Andrews Botanical Garden, possibly the only place that had temperatures above 20 °C during the Scottish winter.