From the 1960s through the early 2000s, most immigrants arriving in Brazil came from the Global North—Portuguese, Americans, and other relatively affluent groups. Few relied on the national healthcare system (SUS) or public schools, opting instead for private services. This was a very different picture from today, when most immigrants in Brazil face vulnerable living conditions. A new edition of Atlas temático (Thematic atlas), published this year by the University of Campinas Center for Population Studies (NEPO-UNICAMP), reveals that about 415,000 immigrants are listed in Brazil’s Unified Registry for Social Programs (CadÚnico)—the federal database used to identify low-income households.

“We found a significant number of immigrants living in vulnerable conditions across Brazil,” explains demographer Rosana Baeninger, the study’s lead researcher. She notes that although Brazil’s immigration laws are relatively progressive, the lack of coordination among federal, state, and municipal levels—due to the absence of a unified, national migration policy—leaves local governments responding in piecemeal, often emergency-driven ways.

Out of Brazil’s 5,570 cities, just 230 have implemented any formal policy addressing the needs of foreign residents. Among them is São Paulo, home to roughly half a million registered immigrants—mostly from Bolivia, Venezuela, and Angola. In 2016, the city passed Law No. 16,478, which established São Paulo’s Municipal Policy on Immigrants and created the Oriana Jara Immigrant Referral and Assistance Center (CRAI).

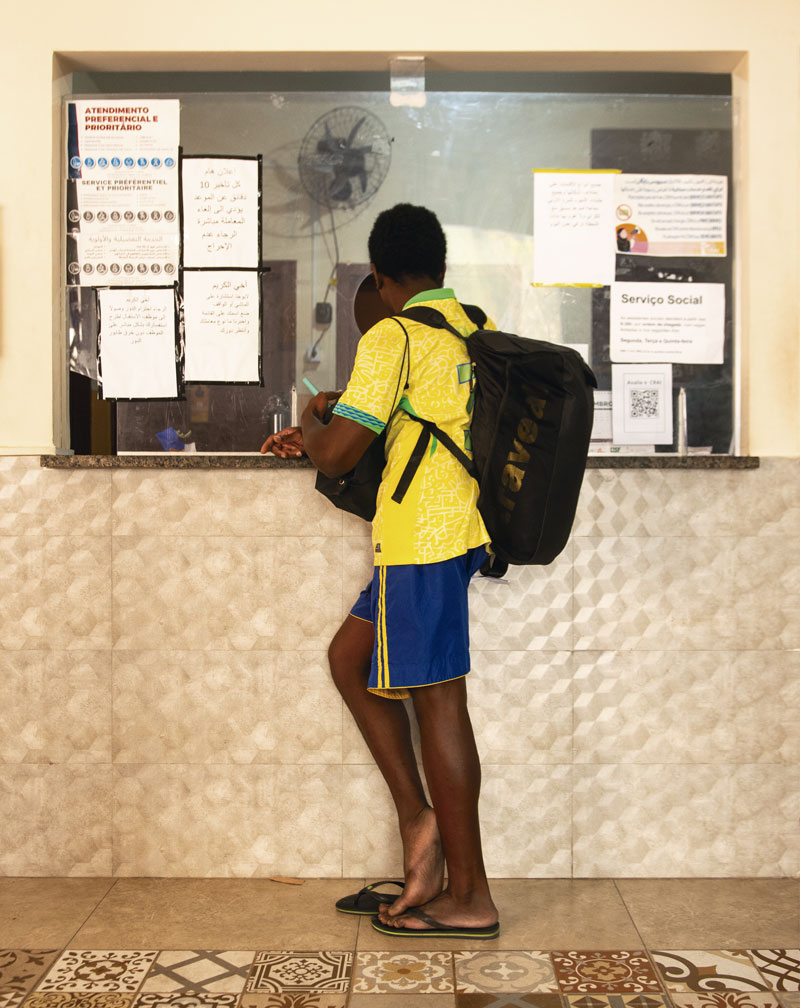

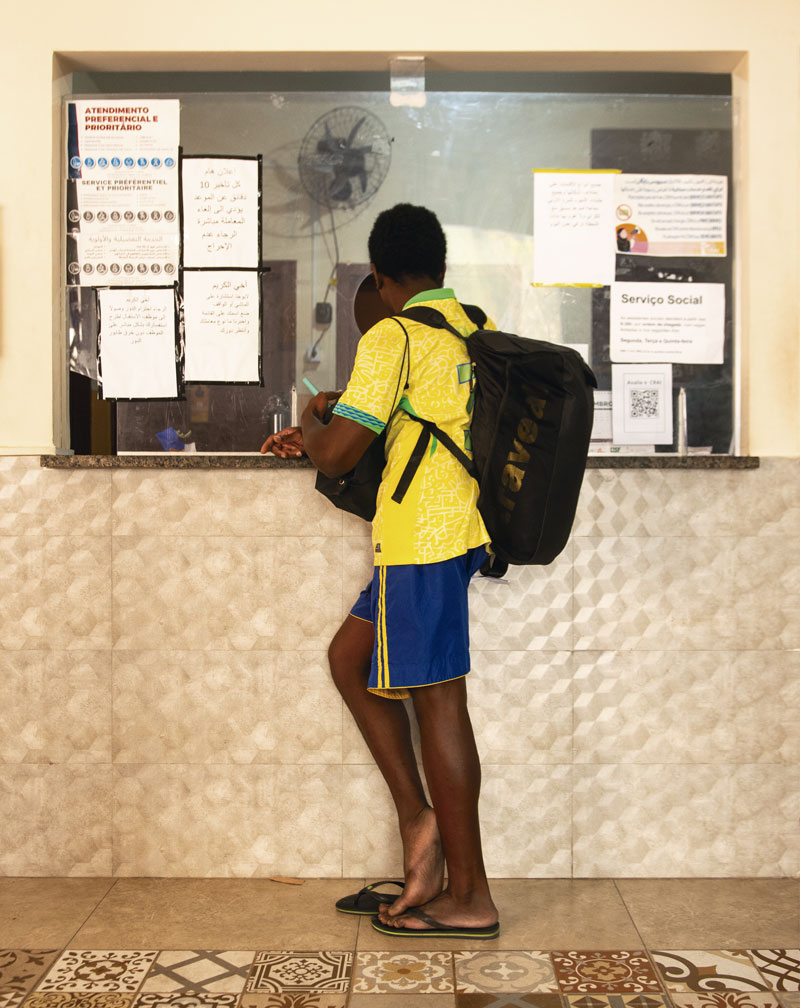

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP A visitor seeking information at São Paulo’s Oriana Jara Immigrant Referral and Assistance CenterLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

Between 2020 and 2025, CRAI provided assistance to more than 46,700 people. Its main office in the Bela Vista district—one of central São Paulo’s busiest neighborhoods—provides services to immigrants from Bolivia, Venezuela, Afghanistan, Angola, Senegal, Nigeria, Syria, and other countries. “People come seeking help with everything from immigration paperwork and school access to legal and psychological counseling,” explains Grevisse Mulamba Kalala, a Congolese management assistant at the center. “We assist people from over a hundred nationalities, many of them vulnerable.”

Among those seeking help at CRAI, Colombian psychologist Ana León, from São Paulo’s Municipal Office for Human Rights and Citizenship, notes a growing stream of unaccompanied children arriving at the center. “In 2025 alone, we assisted 18 unaccompanied children,” says León, who has been living in Brazil for 12 years. León notes that many of these cases are complex, citing, for example, a teenage mother who crossed borders carrying her baby.

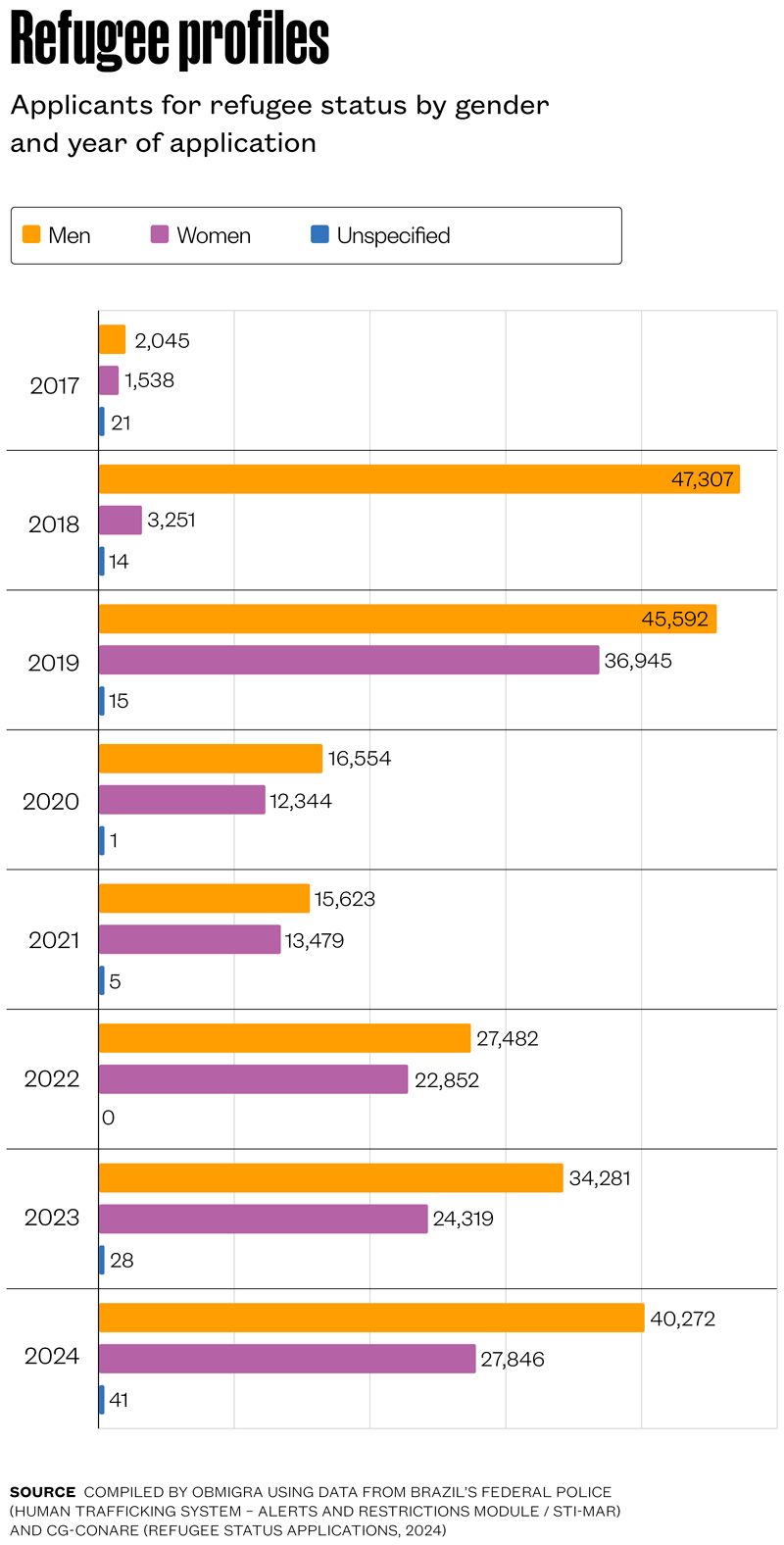

“And that case is far from unique,” she adds. According to the 10th edition of Refúgio em números (Refugees by the numbers), 14,000 asylum requests were filed in the past year on behalf of children under age 15—an unusually high number. In total, the federal government received 68,000 applications for refugee status during that same period (see chart on page 20). This marks the third-highest number of asylum requests in Brazil’s history, exceeded only in 2018 and 2019. Released in 2025, the report is produced by Brazil’s National Committee for Refugees (CONARE) in collaboration with the International Migration Observatory (OBMigra)—a collaboration between the University of Brasília (UnB) and Brazil’s Ministry of Justice and Public Security (MJSP).

Kalala, who has lived in Brazil for 11 years, is one of several immigrant staff members employed at CRAI. He immigrated from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to join relatives who had already settled in São Paulo. A computer engineer by training, Kalala speaks seven languages, among them Swahili, French, English, and Spanish. Like León, Kalala says his biggest challenges in Brazil are limited access to higher education and the bureaucratic barriers to validating foreign diplomas. León waited three years for her degree to be recognized; Kalala, meanwhile, is still waiting to have his diploma validated. The process, he explains, is costly and requires original documents that can only be obtained in person from the immigrant’s home country. “Honestly, it’s often easier to start over and get a new degree than to have your existing one recognized in Brazil,” he says with frustration.

Historian Ana Carolina de Moura Delfim Maciel, who holds the Sérgio Vieira de Mello Chair—a program run jointly by UNICAMP and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR)—notes that some Brazilian universities have special admission policies for refugees and people at risk. According to a report from the Chair, as of 2020, 13 Brazilian universities, including UNICAMP, had adopted inclusive admission policies for refugees. “In 2025, the university’s special admissions program for refugees received over 300 applications from students coming from Ukraine, Syria, Colombia, Venezuela, Angola, Cuba, Ghana, and Iran,” says Maciel.

In collaboration with French anthropologist Michel Agier of the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS) in Paris, Maciel is currently working on a documentary scheduled for release in 2025. The film is part of a FAPESP-funded research project exploring the life trajectories of refugees. “Our project combines academic research and hands-on training,” Maciel explains. “We distributed cameras to 14 refugees from Syria, Ukraine, Afghanistan, Venezuela, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, living in Brazil and France, so they could record their own stories. This is an opportunity for them to document their experiences. Personal stories are often one of the only possessions people take with them when they flee their home countries. We want to give visibility to those voices.”

In São Paulo, a lack of awareness about legal rights—combined with widespread prejudice—is another issue facing immigrants. To better understand the problem, sociologist Jaciane Pimentel Milanezi Reinehr, from the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP), carried out a FAPESP-funded study on Haitian immigrant women’s access to Brazil’s public healthcare system. Her fieldwork, carried out at a primary healthcare unit (UBS), revealed that Haitian women were frequently stigmatized by healthcare providers. “Their behavior—or simply their unfamiliarity with how Brazil’s public services function—was often criticized by health professionals,” Reinehr explains.

Similarly, Jameson Vinicius Martins da Silva, in his FAPESP-funded PhD research at USP’s School of Public Health, found that many immigrants struggle to access healthcare due to language, cultural, and bureaucratic barriers—and, at times, discrimination from healthcare professionals. “On the other hand,” says Silva, who defended his dissertation in 2024, “some healthcare centers in São Paulo have become accustomed to serving immigrant communities and have developed inclusive practices. But this is far from the norm.”

Paulo Pinto / Agência BrasilA local shelter in São Paulo began receiving Afghan refugees in 2024Paulo Pinto / Agência Brasil

In addition to São Paulo, another city with dedicated policies for immigrants is Corumbá, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Developed in collaboration with the Frontier Observatory for International Migration (MIGRAFRON) at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), a 2022 resolution by Corumbá’s Municipal Education Council established guidelines for enrolling migrant, refugee, stateless, and asylum-seeking children, adolescents, and adults in the city’s public schools.

Another core component of Corumbá’s immigrant program is Casa do Migrante, a facility run by the city’s social assistance service that welcomes migrants regardless of their legal status. In 2024, the center provided service to 2,000 immigrants, according to Patrícia Teixeira Tavano, a professor and coordinator of the MIGRAFRON research group. “In addition to housing,” Tavano explains, “we provide meals, support with documentation, and referrals to healthcare and social services.”

Situated along Brazil’s border with Paraguay and Bolivia, Corumbá is home to residents from 28 nationalities—mostly Bolivians, but also Venezuelans, Colombians, Ecuadorians, Haitians, and Palestinians. “Its strategic border location makes Corumbá a major gateway for overland immigrants to Brazil,” Tavano notes.

She adds that, beyond those who settle permanently, many Bolivians cross the border daily to work, attend school, or access healthcare in Brazil—then return home each evening. Cross-border traffic also moves the other way: Brazilians frequently travel to Bolivia to shop or enroll in universities, particularly in medical programs.

Like Corumbá, the city of Dourados, also in Mato Grosso do Sul, lies close to the Bolivian and Paraguayan borders. Hermes Moreira Junior, who runs the Sérgio Vieira de Mello Chair at the Federal University of Grande Dourados (UFGD) in collaboration with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), notes that Indigenous communities from multiple ethnic groups regularly cross these border regions, often without any formal identification documents.

Data from Mato Grosso do Sul’s Public Defender’s Office show that over 200 Indigenous people cross the borders separating Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay every day—without formal registration. “This legal invisibility leaves them extremely vulnerable, cutting them off from even their most basic rights,” explains Hermes Moreira Junior. “And many don’t speak Portuguese,” adds Juliana Tomiko Ribeiro Aizawa, a legal scholar who heads the Mobility, Integration, and Human Rights Research Group at UFGD.

Marcelo Camargo / Agência BrasilVenezuelan immigrants in Boa Vista city (RR), in 2018, in search of housing and employmentMarcelo Camargo / Agência Brasil

Moreira Junior and Aizawa recounted the story of Inocente Arevalo Orellana in a paper published last year. Born in Bolivia in 1979, Orellana hitched a ride on a truck and crossed into Brazil in 2008, reaching Dourados with no official identification or civil records. Because of a psychiatric condition, he spent several weeks living on the streets before being taken in by a religious charity organization.

For over four decades, Orellana lived as a stateless person—someone not recognized as a national by any country. “He had no civil registration or official documents whatsoever—only a baptism certificate,” recalls Aizawa. “In Brazil,” she adds, “he couldn’t even obtain a medical diagnosis or treatment, since he lacked the documents required to access the SUS like a regular citizen.”

In September 2023, Moreira Junior initiated the formal process to have Orellana officially recognized as stateless—a case that had been ongoing for nearly a decade. Orellana could not be identified as Bolivian, since there was no official record confirming his place of birth. The initiative involved a joint effort between Brazil’s Public Prosecutor’s Office, Federal Police, and the Ministry of Justice and Public Security (MJSP), working in coordination with Bolivian institutions—including the Plurinational Consulate of Bolivia in Corumbá.

Orellana’s stateless status was officially recognized at the end of 2023. According to Aizawa, the process took so long partly because Orellana had no formal documents and partly because his mental health issues made communication with authorities extremely difficult. Another factor was the unprecedented nature of the case—Orellana became the first person in Mato Grosso do Sul ever to be officially recognized as stateless by the Brazilian government. Since then, two additional cases of statelessness in the state have also been successfully resolved.

The story above was published with the title “The changing face of immigration in Brazil” in issue 355 of September/2025.

Projects

1. Cities of rights: Health policies for international migrants in the cities of São Paulo (Brazil) and Barcelona (Spain) (n° 18/22974-0); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Deisy de Freitas Lima Ventura (USP); Beneficiary Jameson Vinícius Martins da Silva; Investment R$230,082.84.

2. Trajectories without borders: Memory and trauma of refugees in the contemporary world (n° 23/16222-4); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Ana Carolina de Moura Delfim Maciel (UNICAMP); Investment R$205,430.65.

3. Race and health in transit: Health governance of international migrants in the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo (n° 19/13877-4); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Marcia Regina de Lima Silva (CEBRAP); Beneficiary Jaciane Pimentel Milanezi Reinehr; Investment R$649,615.40.

Scientific articles

AIZAWA, J. T. R. & JUNIOR, H. M. Fronteiras marginais e o primeiro apátrida de Mato Grosso do Sul. Brasília, DF, Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea). Revista Tempo do Mundo. No. 35. 2025.

CHALCRAFT, J. & HIKIJI, R. S. G. Imagens que atravessam. Diáspora africana em performance. Artelogie. No. 16. 2021.

HILIJI, R. S. G. & CHALCRAFT, J. Gringos, nômades, pretos – políticas do musicar africano em São Paulo. Revista de Antropologia. Vol. 5, no. 2. 2022.

MILANEZI, J. Distinções, mediações excludentes e desigualdades: A governança da saúde reprodutiva de “cadastradas difíceis”. Dados ‒ Revista de Ciências Sociais, 67 (2). 2024.

MILANEZI, J. “O problema é cultural: Estigmas, comportamentos e vigilâncias reprodutivas de mulheres haitianas.” In: REIS, Elaine et al. (eds.). Justiça reprodutiva: Desafios interseccionais na saúde coletiva. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz. 2025.

Books

BAENINGER, R. et al. (eds.). Atlas temático: Observatório da emigração brasileira – Observatório das migrações dos países de língua portuguesa ‒ Migrações internacionais. Vol. 3. Campinas: Núcleo de Estudos de População Elza Berquó da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Nepo-Unicamp). 2025.

HIKIJI, R. S. G. Filmar o musicar: Ensaios de antropologia compartilhada. São Paulo: FFLCH/USP. 2025.

MAGALHÃES, L. F. A. et al. (eds). Migrações e refúgio: Temas emergentes no Brasil. Campinas: Núcleo de Estudos de População Elza Berquó da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Nepo-Unicamp). 2024.

Report

JUNGER, G. et al. Refúgio em números 10ª edição. Brasilia, DF. Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública / Departamento das Migrações. 2025.

Republish