reproduction from the book O museu hermético: Alquimia & Misticismo, by Alexander RoobIn “The alkahest or the search for the Absolute,” in The Human Comedy, Balzac narrates the tragic obsession of Balthazar Claës, a disciple of Lavoisier, holed up in his laboratory to discover the process of transforming carbon into pure diamonds; to this end, he abandoned his family and squandered his fortune on chemical products. The story is strangely “incoherent” because it shows a follower of the creator of modern chemistry, a distinguished representative of rationalist science, tarnishing his reputation by resorting to nebulous medieval knowledge, clearly related to alchemy. Unwittingly, Balzac, by means of fiction, touched upon a still sensitive nerve in the history of science: knowledge of alchemy and the hermetic tradition were not easily eliminated by the scientific revolution, having remained alive for many centuries in different forms and at different levels. The latest documented evidence of these parallels and permanencies between different moments such as the ones that generated medieval hermeticism and gave rise to modern science has just been discovered in London in the archives of the Royal Society, by Ana Maria Alfonso-Goldfarb and Márcia Ferraz, from the Centro Simão Mathias de Estudos em História da Ciência/CESIMA center for studies on the history of science at the Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP). The evidence is comprised of documents from the seventeenth century, formerly believed to have been lost. In these documents, the members of this venerable British institution, a pioneer in promoting modern scientific knowledge, discuss the legendary alkahest (and its “formula”), alchemy’s hypothetical “universal chemical solvent,” which can allegedly dissolve any substance by reducing it to its primary components.

reproduction from the book O museu hermético: Alquimia & Misticismo, by Alexander RoobIn “The alkahest or the search for the Absolute,” in The Human Comedy, Balzac narrates the tragic obsession of Balthazar Claës, a disciple of Lavoisier, holed up in his laboratory to discover the process of transforming carbon into pure diamonds; to this end, he abandoned his family and squandered his fortune on chemical products. The story is strangely “incoherent” because it shows a follower of the creator of modern chemistry, a distinguished representative of rationalist science, tarnishing his reputation by resorting to nebulous medieval knowledge, clearly related to alchemy. Unwittingly, Balzac, by means of fiction, touched upon a still sensitive nerve in the history of science: knowledge of alchemy and the hermetic tradition were not easily eliminated by the scientific revolution, having remained alive for many centuries in different forms and at different levels. The latest documented evidence of these parallels and permanencies between different moments such as the ones that generated medieval hermeticism and gave rise to modern science has just been discovered in London in the archives of the Royal Society, by Ana Maria Alfonso-Goldfarb and Márcia Ferraz, from the Centro Simão Mathias de Estudos em História da Ciência/CESIMA center for studies on the history of science at the Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP). The evidence is comprised of documents from the seventeenth century, formerly believed to have been lost. In these documents, the members of this venerable British institution, a pioneer in promoting modern scientific knowledge, discuss the legendary alkahest (and its “formula”), alchemy’s hypothetical “universal chemical solvent,” which can allegedly dissolve any substance by reducing it to its primary components.

Ana is the coordinator of a FAPESP-sponsored thematic project that focuses on the complex transformation of the science of matter: the combination of ancient knowledge and modern specialization. When working on their research project in London, the two researchers, after an intensive search, came across the aforementioned documents. “We insisted on sharing these findings with the Royal Society. In the middle of next year, together with professor Piyo Rattansi, from University College London, who helped us transcribe and analyze the documents, we are going to present the re-discovered manuscripts and publish an article on the findings in the journal Notes and Records of the Royal Society,” says Ana. The historians have almost completed the translation of the texts and the original manuscripts will remain in the archives of the Royal Society. “The directors of the Royal Society were wildly enthusiastic about our findings when we presented them, because they realized the importance of these documents for the history of science, even though they hadn’t been previously identified and studied,” she says. “This is the only complete formula (with just one or two words in code) that has ever been found for alkahest and, based on these documents, we will become even better acquainted with the “backstage” of the great science of those times.” CESIMA already had the digital version of the British society’s documents, which made the on-site work easier, but the recent findings had not been revealed.

The researchers do not take the idea of a “universal solvent” literally. “In modern terms, it is not actually a solvent, but for the best scientific brains of those times, it was the zenith of what could be understood then as a universal solvent,” says Márcia. The researchers are not interested in testing the discovery in a lab and do not believe that this could actually be done, as many of the materials might still have the same names nowadays without being those specified in the formula. “Modern-day attempts at putting alchemy formulas into practice have usually been a failure, because there are a number of factors to be taken into account. When the formula calls for ‘the excrement of bats from caves in Mesopotamia,’ what substance can replace it?” According to the historians, the real importance of these documents is to re-examine to a greater extent, on the basis of documents, the common belief that alchemy, based on a chain of mysteries, did not resist the shift to a rational, mechanical world, in which mysteries are unacceptable, having disappeared entirely between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, replaced by modern chemistry, and transformed into a mere “figure of speech.”

“The so-called alchemy ideas, under another name, continued to intrigue the brilliant brains that we know as being the representatives of modern science. Even when amongst their peers they stated that they were against these ancient processes, they still applied them to their work,” says the researcher. “The beauty of the history of science is that there is no single reason, but several reasons over a period of time, that often come together. The relationship between alchemy and chemistry lasted until the middle of the nineteenth century, in the form of a ‘secret agenda’ of such prominent figures as Newton, Boyle, Pascal, Boerhaave, among others.” The concept of alkahest, or the idea that it would be possible to obtain a universal solvent able to dissolve materials and that would not be “marked” by these substances, began to take shape on the basis of a vague statement voiced by Paracelsus (1493-1541), in De viribus membrorum, where, in the chapter on how to cure liver diseases, he refers to a universal solvent which allegedly preserved the liver and could even take on its functions, if it were damaged. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the search for alkahest became an obsession among the followers of the Swiss physician. The healing power of alkahest greatly aroused the interest of Belgian physician Joan van Helmont (1579-1644) who, based on the words of Paracelsus, tried to obtain the formula of the solvent. He believed that alkahest would be better than fire, as, unlike fire, which retains matter in ashes after combustion, alkahest would separate the substances without being affected by them. The Belgian was interested in the medical aspects of the substance: such a solvent able to retain the prima entia of bodies would have tremendous healing powers, as this was a safe and non-destructive way of obtaining the medical virtues of the “simple” elements. Van Helmont believed that alkahest would be the medicine that would cure all diseases, but that it could only be obtained as “a gift from God to someone who deserved this gift.” Non-stop and unfruitful searches led to the demise of interest in alkahest, which even became the butt of jokes among chemists, who viewed it as a chemical nightmare. Nonetheless, such renowned scientists as Starkey, Glauber and even Robert Boyle (The skeptical chemist) were interested in the concept of the Belgian’s universal solvent and believed that such a solvent could be obtained.

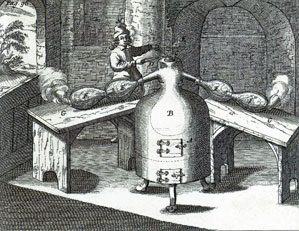

reproduction from the book O museu hermético: Alquimia & Misticismo, by Alexander RoobThis is why the discovery of these documents and the resulting discussion at an institution such as the Royal Society are so important. The Society’s motto, Nullius in verba, emphasizes the wish to establish the truth within the domain of facts, based solely on scientific experiments. The documented evidence that serious discussions were held on the universal solvent of the alchemists, which involved the society’s most prominent members, such as the first secretary of the Society, Henry Oldenburg (1619-1677), and Jonathan Goddard, once again focuses on the issue of the continuity of alchemy into the age of reason. In a way, this is reflected in the fantastic story of the discovery of these manuscripts, which, far from being something magic, was, as Ana points out, the result of “a solid hypothesis and dogged persistence” of the two researchers. The “solid hypothesis” derived from the several entries in the Royal Society’s Book of Minutes of 1661, which had references about its members’ interest in the search for a “universal solvent.” This was nothing new, as these comments could be read by anyone with access to the digital microfilms of the Society’s library. The missing elements were the documents to which such comments referred. Nobody had been able to discover this. “This reinforces the importance, which is not fully acknowledged nowadays, of working directly with original documents stored in big libraries, and of refusing to give in to the temptation provided by the illusion of technology to make research more comfortable, that can lead many researchers to consider only the existence of documents in digital form.”

reproduction from the book O museu hermético: Alquimia & Misticismo, by Alexander RoobThis is why the discovery of these documents and the resulting discussion at an institution such as the Royal Society are so important. The Society’s motto, Nullius in verba, emphasizes the wish to establish the truth within the domain of facts, based solely on scientific experiments. The documented evidence that serious discussions were held on the universal solvent of the alchemists, which involved the society’s most prominent members, such as the first secretary of the Society, Henry Oldenburg (1619-1677), and Jonathan Goddard, once again focuses on the issue of the continuity of alchemy into the age of reason. In a way, this is reflected in the fantastic story of the discovery of these manuscripts, which, far from being something magic, was, as Ana points out, the result of “a solid hypothesis and dogged persistence” of the two researchers. The “solid hypothesis” derived from the several entries in the Royal Society’s Book of Minutes of 1661, which had references about its members’ interest in the search for a “universal solvent.” This was nothing new, as these comments could be read by anyone with access to the digital microfilms of the Society’s library. The missing elements were the documents to which such comments referred. Nobody had been able to discover this. “This reinforces the importance, which is not fully acknowledged nowadays, of working directly with original documents stored in big libraries, and of refusing to give in to the temptation provided by the illusion of technology to make research more comfortable, that can lead many researchers to consider only the existence of documents in digital form.”

For previous scholars, material that was not included in the digital catalogue did not merit or need to be researched. Ana and Márcia, who were not in search of the aforementioned formula, but were interested in analyzing Goddard’s papers, felt that there was something unusual in the documents, especially in the archives’ so-called “closed-end” documents. “We came across memoirs that resembled treatises on modern chemistry, yet contradicted modern science’s common sense, such as “silver is not silver,” and so on. So we started looking for the unpublished documents,” they say. To complicate things, the compound was spelled “alchahert” in the on-line catalogue, which made it impossible to find it through a digital search. The researchers also noticed that the classification in the archives followed a specific reasoning, coherent with seventeenth century thinking, and this could mislead the contemporary researcher. “So we decided to conduct our search by following the classification criteria that someone from that century would have followed to classify and store information.”

The clue lay in one of the digital drafts, in the form of an intriguing comment: “May Goddard’s text be transcribed, for better reading, and may the recipe for alkahest be guarded with all care.” The historians decided to focus on searching for the lost records of the four meetings held at the Society in October and November 1661. They concluded that it would be worthwhile examining the Oldenburg papers as well. “British librarians were curious and suspicious about the two Brazilian women who kept asking for more and more documents and archives,” Ana recalls. The two researchers finally came across a manuscript in Latin, which referred to “an animal liquid similar to alkahest.” The manuscript, as stated in the minutes, had been read by the secretary to an audience comprised of doctors from the Royal Society. The records stated that Oldenburg had appointed Goddard to analyze the manuscript and make the necessary comments on the content. Goddard did as requested, stating the pros and cons of the possibility that the said liquid was the universal solvent, and presented his conclusions at another meeting. To everyone’s surprise, a formula for alkahest itself was also mentioned at this second meeting, as shown in another document found by the researchers. Oldenburg’s response to Goddard’s opinion, presented at a later meeting, is yet to be found. The researchers believe that this document will be found as they continue researching the archives. But through intelligence and hard work, the historians had already found information that so many researchers in the course of centuries had not bothered to look for, despite its importance.

“The core of the whole issue was a physiological discussion related to the recent and early discoveries of Thomas Bartholin in 1653, (and, at the same time, of Olaus Rudbeck) on the existence of the lymphatic system.” At that time, doctors did not really understand the lymphatic system and the general opinion was that it might function as “a universal solvent” able to dissolve what was harmful to the body without acquiring traces of what had been dissolved. This ignorance was normal, as the lymphatic system was only understood in 1746, when William Hunter thoroughly analyzed the function and the role of the lymph ducts. “There was a belief that the lymphatic system had this solvent function, but as this hypothesis could not be tested inside a human body, it was necessary to devise a formula to conduct the in vitro experiment in a laboratory,” Márcia explains. “The aforementioned scientists firmly believed that they had found a universal principle, in line with the universal ideal of the seventeenth century. As a result, half of Europe was looking for the universal solvent while the other half was trying to understand the lymphatic system in medical terms. Therefore, they may have included all these conjectures in those documents.” But how would Oldenburg have obtained the alkahest “formula”?

“He was an important link in this group of geniuses who secretly discussed these and other topics in those times; this group included people like Spinoza and Huygens, among others, most of whom lived in the Netherlands and in what would later become Germany. Oldenburg, who was German, was the perfect person to act as the British link,” says Ana. On a trip to the continent, the secretary met a friend, a Doctor Colhans, whose surname was the same as that of astronomer Johann Christopher Colhans. “This made things more difficult and generated more confusion when it came to looking for the manuscripts, because researchers had always thought that Oldenburg’s references to Colhans referred only to the astronomer. Oldenburg, however, spelled the doctor’s name with a ‘C’ and that of his colleague with a ‘K’,”says Márcia. The important detail, which many researchers had been unaware of because of this error, was that Colhans, the doctor, was a very close friend of Franciscus-Mercurius, son of Joan van Helmont and editor of the works of the tireless researcher of Paracelsus’ alkahest formula.

reproduction from the book O museu hermético: Alquimia & Misticismo, by Alexander RoobThe historians believe that it is possible to establish a theory, thus rounding everything out, to understand what had happened: Joan van Helmont might have devised a formula for a “universal solvent” and his son might have delivered this to Colhans, who, in turn, prepared a second document linking alkahest to the recent discovery of the lymphatic system. It seems that both documents were then forwarded to Oldenburg. Upon returning to England, the secretary brought together a select group to whom both documents were read, including the formula of the famous alkahest, asking the respected Goddard to provide an opinion on the real possibilities of the solvent. Goddard presented his comments to the group, in his terrible handwriting, hence the recommendation that the “document be transcribed in order to be more legible and that the alkahest formula be carefully protected.” The historians’ dogged persistence resulted in a strong hypothesis. But what was the reason behind so much secrecy? In contrast to common belief, the reason might not be the “shameful” research of the “mysteries” of alchemy. “Hermetic treatises and formulas of this kind were considered, even in those times, as State secrets, since they included information on how to manipulate metals and other materials for military and medicinal purposes, or even for the production of such expensive and superfluous items as stained glass,” says Ana. This might be the reason for the existence of the so-called “books of secrets,” because these books literally kept “trade secrets” under lock and key. Oldenburg, for example, was recognized for his talent in keeping such secrets and extracting secrets from others whenever possible.

reproduction from the book O museu hermético: Alquimia & Misticismo, by Alexander RoobThe historians believe that it is possible to establish a theory, thus rounding everything out, to understand what had happened: Joan van Helmont might have devised a formula for a “universal solvent” and his son might have delivered this to Colhans, who, in turn, prepared a second document linking alkahest to the recent discovery of the lymphatic system. It seems that both documents were then forwarded to Oldenburg. Upon returning to England, the secretary brought together a select group to whom both documents were read, including the formula of the famous alkahest, asking the respected Goddard to provide an opinion on the real possibilities of the solvent. Goddard presented his comments to the group, in his terrible handwriting, hence the recommendation that the “document be transcribed in order to be more legible and that the alkahest formula be carefully protected.” The historians’ dogged persistence resulted in a strong hypothesis. But what was the reason behind so much secrecy? In contrast to common belief, the reason might not be the “shameful” research of the “mysteries” of alchemy. “Hermetic treatises and formulas of this kind were considered, even in those times, as State secrets, since they included information on how to manipulate metals and other materials for military and medicinal purposes, or even for the production of such expensive and superfluous items as stained glass,” says Ana. This might be the reason for the existence of the so-called “books of secrets,” because these books literally kept “trade secrets” under lock and key. Oldenburg, for example, was recognized for his talent in keeping such secrets and extracting secrets from others whenever possible.

It is important to keep in mind that the invention of the printing press in itself did not ensure the mass disclosure of scientific knowledge, something that would only take place in the nineteenth century. We are referring to knowledge that was shared by very few people, made by few people for few people. This was a second agenda for new scientists, among whom was Isaac Newton. In fact, Sir Isaac is an example that has bothered many historians, ever since John Maynard Keynes, as the story goes, allegedly purchased Newton’s desk at an auction and found, in the false bottom of the desk, texts on alchemy, magic and religion. “There was an immediate reaction. The history of science had focused solely on knowledge that had some kind of relationship with modern science and which, because it had evolved, was part of issues that deserved to be studied and reported. The concept of science was closely linked to the concept of progress, which implied, in the course of time, that the ancient were less knowledgeable than the medieval scientists, and the medieval scientists were less knowledgeable than the contemporary scientists,” says the researcher. She adds that, according to this view, “there was no room in which to understand the different ways of ‘knowing’ different authors from different times, times which differed greatly from our times, yet were still valid in their own contexts.”

“In fact, many of the works that generated modern science seem to be on a threshold. On one hand, they captured many elements of this complete logic of knowledge from the past. On the other hand, they initiated contact with a new cosmology and new ideas that would come to replace prior knowledge.” This is the reasoning behind Keynes’ famous words: “Newton was not the first man of the age of reason; he was the last man of the age of magicians.” These words, however, should not be taken literally, nor be viewed as sensationalism, the historians point out, as if we had discovered the scientists’ “peccadilloes”. “Newton, for example, practiced occult sciences with pragmatic objectives and with the instruments of a serious researcher. He had one foot in alchemy and another foot in science, thus opening up possibilities that more rational scientists were unable to envision,” says Piyo Rattansi. “We think along the lines of the ultra-specialization parameters of our culture. Newton used all the means then available to search for knowledge and truth. The study of alchemy allowed him to develop revolutionary scientific concepts.” The researcher, who helped the Brazilian historians, says that the discovery of the manuscripts reveals a new aspect of the discussions that took place in the middle of the seventeenth century on the link between alkahest and the lymphatic fluid studied by the anatomists of those times, still another proof that it was possible to link such different ideas.

Therefore, the documents on alkahest reinforce the need to take the continuity of alchemy-related knowledge into account, something which many people believe is dead and buried and can be replaced by modern chemistry, especially because the universal solvent, although it is important, is not the only case of overlapping ideas presented at the Royal Society. “Very few people in the eighteenth century conducted the intense chemistry experiments of the kind conducted by Hermann Boerhaave, which helped establish modern experimental standards,” says Ana. “Perhaps this is why so many scholars viewed him only within the context of the Age of Reason. But he conducted important investigations on traditional alchemy foundations, without losing sight of the parameters of his own time.” In the words of Boerhaave himself: “Alchemists from the past, in opposition to contemporary chemists, acted much more wisely and correctly.” As the researchers point out, he is a good example, though not the only one, of how alchemy-related “experiments” were converted by many important people from the Age of Reason into new experimental standards, yet still in line with assumptions that were very close to those of the ancient alchemists, who coexisted, in the form of a second agenda, with the creation of new, modern science. “This explains the persistence of ancient sources of science from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in texts seen as radically modern until very recently,” Ana points out. Alchemists are still around.

The Project

The complex transformation of the science of matter: between the elements of ancient knowledge and modern specialization (99/12791-3); Type: Thematic Project; Coordinator: Ana Maria Alfonso-Goldfarb – PUC-SP; Investment: R$ 678,511.91 (FAPESP)

Scientific articles

ALFONSO-GOLDFARB, A. M.; JUBRAN, S. A. C. Listening to the whispers of matter through Arabic hermeticism: New studies on the Book of the Treasure of Alexander. Ambix (Cambridge), v. 55, p. 99-121, 2008.

ALFONSO-GOLDFARB, A. M.; FERRAZ, M. H. M. “‘Experiências’ e ‘experimentos’ alquímicos e a experimentação de Hermann Boerhaave”. In: Ana Maria Alfonso-Goldfarb; Maria Helena Roxo Beltran. (Orgs.). O saber fazer e seus muitos saberes: experimentos, experiências e experimentações. São Paulo: Educ/ Editora Livraria da Física, 2006, p. 11-42.

Porto, P. A. Summus atque felicissimus salium: The medical relevance of the Liquor Alkahest. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, v.76, p. 1-29, 2002.